#222 Production by Licensing Imports (PLI 2.0)

The Laptop Import License Raj, Electronics Manufacturing in India needs Chinese Companies, and Why Large Indian States Need to be Broken Up.

Course Advertisement: Admissions for the Sept 2023 cohort of Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy programme are now open! Three specialisations; equal fun. Visit this link to apply.

India Policy Watch #1: Ah, That Smell of License Raj In The Air

Insights on current policy issues in India

— RSJ

In a week when Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahaani made India wistful of the past with its beautiful blending of songs from the golden age of Hindi film music (1950-70s) into its plot, the government thought it could do one better in putting us in a time machine and sending us half a century back. And so we had this beautiful piece of nostalgia supplied to us by one of our favourite institutions, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT).

The Union government has restricted imports of personal computers, laptops, palmtops, automatic data processing machines, microcomputer/ processors and large/ mainframe computers with immediate effect. The move seems to be aimed at promoting domestic manufacturing, and probably targeted at China since more than 75 per cent of India’s total $ 5.33 billion imports of laptops and personal computers in 2022-23 was from the neighbouring country.

In a notification issued Thursday, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) said imports of computers and other items under the seven categories of HSN Code 8471 (HSN is the Harmonised System of Nomenclature, a globally accepted method of naming goods) were restricted. There will, however, be no restrictions on imports under the baggage rules.

The move is being seen as a direct boost to the Centre’s recently renewed production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for IT hardware. A senior government official said the measure is to push companies to manufacture locally in India, as the country looks to strengthen its domestic production prowess in the electronics sector.

And like all such notifications, there is exquisite fine print stuff included in this. For instance:

Imports up to 20 items per consignment for R&D, testing, benchmarking, and evaluation repair and re-export, and product development purposes, have also been exempted from import licence. Such imports will, however, be only for use for the stated purposes and not for sale. “Further, after the intended purpose, the products would either be destroyed beyond use or re-exported,” the notification said.

Of course, what’s a notification like this worth if there’s no clarification or deferment the next day because of the confusion that it triggered. So, on Saturday, it issued this note:

In a relief for electronic companies, the government today deferred the plan to curb laptop and tablet imports by three months. Companies will have time until October 31 to secure a license to import the devices, the government said in a notification.

This is a partial reversal from a surprise decision on Thursday to impose the licensing requirement with immediate effect, which had prompted calls for a delay.

The government said the restrictions were imposed for security reasons and the need to promote domestic manufacturing. The move will also curtail in-bound shipments of these goods from countries like China and Korea and also allow the Centre to keep a close watch on the locations from where the products are coming, officials said.

All quite predictable.

Now, dear reader, there are multiple directions I can take you from this policy announcement. The amusing thing is I can take you there without adding any context and yet, they will all make sense to you.

For instance I can take you to these extracts of speeches by PM Nehru in the 50s:

"Previously people’s idea of industrialisation was one of increasing the output of consumer goods, with consequent employment. The idea now is … we must start from the heavy, basic, mother industries. … We must start with the production of iron and steel on a large scale. We must start with the production of the machine which makes the machine.

One thing is clear to me that if we do not develop heavy industry here then we either eliminate all modern things such as railways, airplanes and guns, … or else import them. But to import them from abroad is to be slaves of foreign countries.”

I took these extracts from this article by Dr. Arvind Panagariya who till a few years back was in an advisory role to the government. Dr. Panagariya writes:

“The strategy brought with it many unintended consequences. All available capital was reserved for heavy industry. Given the meagre amount of capital, the scale of production in each product line within heavy industry still remained suboptimal. In parallel, light manufactures were relegated to household and small enterprises where they too remained subject to production at suboptimal scale. With higher inflation at home than abroad and a fixed exchange rate, most products soon became uncompetitive against their foreign counterparts and had to be protected through strict import licensing.

Heavy industry created few jobs for the unskilled. Simultaneously, the demand for light-industry products and services remained constrained by domestic incomes, which grew at a snail’s pace. The result was a painfully slow transition of workers from below-subsistence agriculture into industry and services. The proportion of workforce in agriculture, which stood at 69.7% in 1951, remained stuck at 69.5% in 1961 and 69.7% in 1971. No reduction in poverty was achieved.”

Or, I can take you to this story of the celebrated entrepreneur N.R. Narayana Murthy that he often recounts:

There was also such a strict licensing regime to import a computer that it took me three years and I went about 50 times to Delhi. Those days I couldn’t afford a flight, so I took a train. I had to stay in some seedy place near Old Delhi Railway Station. Even that cost money for a fledgling company.

For new companies, there was such a heavy tariff because even before you got a license, 50 visits meant — even if it was $500 a trip (at that time, it was Rs 6 per dollar) — $25,000 spent on a $100,000 computer before you bought it or got a license.

The officers did not know anything about computers. They would quibble about small things. Why do you need 64MB of memory? Go with only 48MB, they would say. Let’s say, if one got a license after two years of running around, one would discover that the models one got the license for had become old in the US. India was always three generations behind. Once licensing was abolished, it allowed companies to make decisions in their boardrooms rather than in the corridors of North Block.

Or, I can take you to a post of ours from three years back. Back then, we would have our mythical readers post questions to our equally mythical Economics professor named Prof. Arthananda Ilyich Smith-Hayek (AISH), a home-grown economist without a single videshi bone or cartilage in him. The idea was to debunk common misperceptions about economics that people had. The very first question that we asked him was about the idea of being atmanirbhar. I will reproduce parts of it here because there is no better time to explain once again why imports aren’t necessarily bad or trying to be atmanirbhar can be counterproductive, as our post-independent economic history has shown:

Q1. Dear Prof, we are a big country with so many talented people. NASA, Google, Microsoft, Apple, Whatsapp – all these great institutions will collapse if we Indians decide to boycott them. Why shouldn’t we make everything in India and become a world leader? Why shouldn’t we substitute all these with Indian products?

Yours etc

Bharat Jayjaykar

Dear Bharat, there’s no reason why we shouldn’t aim to be more self-reliant by making more products domestically. But like most things in life, we should be careful about how far we go with this philosophy. Taken to an extreme, this will lead to autarky. Not a good outcome. Let’s first look at what happens if we stretch self-reliance beyond economic reason.

Consider your family as an economic unit. Maybe you run a company that manufactures solar panels and your spouse works for an IT services company as an engineer. You have school-going kids who are dependent on you for their needs. You employ a cook and domestic help at home. You and your spouse like spending time at your kitchen garden during your leisure. As your garden blooms with herbs, vegetables and flowers, you realise the price you pay for them in the market is exorbitant compared to what it takes to grow them at home. You are soon questioning everything you buy from the market – milk, juices, clothes, soaps, food grains, your kids’ tuition and entertainment. Everything would be cheaper and safer if you made them at home. You can see where this is going. Will you start making all of them at home?

You find the question absurd. The obvious answer is no. Why? First, you don’t have time to make all of them at home even if you devote all your spare time and consider putting your kids to work on them too. Also, you won’t be good at raising cows, tailoring or at growing paddy in your garden. Lastly, you and your spouse are good at your jobs. If you spend your time learning more about your work, you will get richer rewards. So, it just doesn’t make sense for you to make everything at your home. Sure, you will still do a few things predominantly at home. For instance, you can’t imagine eating restaurant food every day. So, you will cook food at home on most occasions. Or, maybe you will always use herbs from your garden rather than buying it from outside. But these will be limited based on your priorities.

It is actually not a huge leap of imagination to extend this model to a country. There are natural resources, climate, land, technology and people that any country is endowed with for it to use productively. A country gets better at producing a few goods or services over time while it either doesn’t have resources or expertise in making others. So, it buys them from other countries who are good at making them. Now, it is possible that the country has spare resources (people or otherwise) that it can put to use to make a whole lot of things within its boundary. The question is which of these things should the country start making at home rather than buying from outside? The country can’t indiscriminately decide to make every single product at home. The criteria to decide this could include – what it might be good at making based on its assessment of our capabilities, what it could make in large volumes so it might even sell it to others and profit, and what could be high on priority for it like safety and security of its citizens.

If you follow the above, you will realise we have to carefully choose our bets in areas we want to be self-reliant. This will yield a smaller basket of products and services that we can target in being world-class producers.

We must not forget if we start closing our doors to others indiscriminately, they will start doing the same to us. This will be a zero-sum game. Specialisation and comparative advantage are real constructs. They help everyone gain. It is obvious to us when we apply that to our daily lives at home. It can seem a bit non-obvious when we think of it for a country as large as ours. But, trust me, it is no different.

Also, there’s a paradox in pursuing the goal of self-reliance for any country. Let me explain how.

One can be self-reliant at multiple levels. The highest level (level 1) of self-reliance is when an economic unit can produce and consume everything by itself. No country in the world has reached this level.

The slightly relaxed condition of self-reliance (level 2) is when one can afford to buy what they want irrespective of who produces it. This level can be achieved by becoming rich. If you are rich, you can pay to buy any service you want. Even if the service provider asks for more, you have the wherewithal to buy that.

The lowest level of self-reliance (level 3) is when you cannot produce what you want and neither do you have the economic wherewithal to afford everything you wish. However, you do have enough diversified relationships with many producers of items that are really critical for you. So, you get what you want in your time of need from at least one of them.

India seems to aspire to reach level 2 – the slightly relaxed condition of self-reliance. Fair enough. To get there, we need to become rich. To get rich, we need investment and expertise from abroad. In other words, you need to rely on others. Just like Japan, China, and South Korea did on their journey to get rich. So, and this is important for you to understand, how we proceed towards becoming self-reliant is just as important as the goal. If we close our economy to the world in our search for level 1 self-reliance, we will not even achieve level 3 self-reliance.

There are maybe four reasons that I hear from people supporting moves like laptop import licensing or higher duties on imports of goods that we want to make in India. I will briefly discuss them and the logical counter to each one of them.

First, we need more manufacturing jobs because we aren’t transitioning labour out of agriculture fast enough. Our demographic advantage window is brief, and we risk becoming older before becoming richer. We have a huge market that these MNC laptop and electronic equipment makers drool over. We should ask them to manufacture in India as the toll they need to pay to access this market.

Few things to get straight here. We always had a huge population. We became an attractive market because in 1991, and for a couple of decades thereafter, we opened up our economy, dismantled duties and trade barriers, and started figuring out our comparative advantage. We became prosperous and, therefore, a market that companies cannot avoid. We are inverting this logic by saying since our market is large, we can undo the good work and become protectionist to have these MNCs dance to our tunes. Well, if you do so seriously, you will soon not remain the attractive market you think you are.

Second, a lot of these goods that we are putting under the licensing regime (or levying high duties on) are imported from China. Therefore, we have national security implications here. We need ‘trusted’ sources for goods like these; otherwise, who knows what kind of information China will be accessing from flooding these products in our market.

There is some logic here. We should stay clear from China on strategic and national security stuff. But we must rethink calling entire sectors (personal computing devices and all their components or the entire electric vehicle ecosystem) as ‘strategic’ with national security implications. It just doesn’t make sense. To have the entire supply chain of these sectors move to India immediately to satisfy the ‘make in India’ requirement is bizarre. We should either choose the specific components that we believe require ‘trusted’ sources or manufacture them in India, or we should identify the buying units in India that are strategic (like defence or finance) who must not buy from such partners. To put the whole sector as strategic is plain lazy and will be counterproductive.

Third, there is this oft-quoted success story of the PLI scheme for mobile phone manufacturing that is used as an example of what can be achieved in computer manufacturing too. In FY 18, India imported mobile phones worth $3.6 billion, while its exports were only about $0.34 billion. In FY 23, the imports had fallen to $1.6 billion while the exports rose dramatically to about $11 billion.

Now, this data has been seriously examined by a team of economists headed by Dr Raghuram Rajan (see link), who argue that the PLI subsidy is paid only for finishing the phone in India, not on how much value is added by manufacturing in India. "So India still imports much of what goes into the mobile phone, and when we correct for that, it is very hard to maintain that net exports have gone up," they contend. I tend to re-read Dr Rajan’s research these days because I suspect an ideological slant might have crept up in his work. On this, I agree with a few points made by him. We must use value added as a metric because that will reflect true manufacturing uptake in India. And, it is a bit early to call PLI a success because we should be doing a multi-factor analysis of its impact. For instance, we don’t know what impact this has had on jobs or pricing and subsequent knock-on effects. Clearly, we aren’t seeing a huge job uplift yet because of mobile phone manufacturing and ancillaries business booming. The data on calling it an unqualified success is yet to come.

Lastly, a lot of commentators have made the point that the government seems to have taken this step as a reaction to the zero interest it has seen from manufacturers in its 2.0 version of the PLI scheme for computer manufacturers. Apple, which seemed to have committed to a plant, backed out, stating it will consolidate laptop manufacturing in Vietnam and have mobile phones done in India. Apparently, this might have upset the government, which believes they have the right to demand more given they are giving these manufacturers access to the large Indian market. I find this strange. I mean, if an incentive scheme isn’t working (while apparently, others are), then it is useful to introspect and ask what will work instead. To swing to the other extreme and introduce a retrograde licensing arrangement to teach them a lesson suggests an early 90s Shah Rukh Khan Darr model of trying to win a girl. It doesn’t work. A lot of commentary is also about how Western countries are also turning increasingly protectionist. So, what’s the harm if we, too, go down that path? Well, I guess because others are doing something that’s fundamentally wrong, it doesn't make it right.

There don’t seem to be strong economic voices advising the government about the long-term implications of such moves. Or, maybe, the government knows about it but continues to pursue this course for short-term gains and for the inherent emotional appeal of such steps. Either way, we can’t do much about it except cry ourselves hoarse.

The government and the people want to repeat history. Who are we to get in the way?

Addendum

— Pranay Kotasthane

The Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme has now morphed into a Production by Licensing Imports (PLI) scheme.

A great deal of energy is being spent by the government and its supporters to prove why an import licensing regime on computers does not constitute a license raj.

Duh! Indeed, the infamous license raj had many more controls, not just on imports but also on manufacturing, inputs, and outputs. I concede that the creeping protectionism over the last six years has not yet reached the heights of the pre-1991 era. Thank globalisation for that. Today, national champions also rely on global supply chains, and hence even an over-eager, autarky-wishing government can’t attempt all instruments that were available at the height of the license-quota-permit raj.

But that’s hardly the point. What unites the two licensing regimes is the espoused “theory of change”. Both rest on the assumption that imports are evil and inimical to domestic production. There were a different set of valid reasons for the original licence raj; based on assumptions that made logical—if not practical—sense. For example, the consensus back then was that foreign exchange could be saved only by reducing imports. The idea that imports could generate more exports after value addition and hence more foreign exchange was far outside the Overton Window. We are still clinging to derivative versions of that theory of change. It failed then, and it will fail now.

Regardless of the motivation, the unintended consequences of this license-tariff-raj are easy to anticipate. Cheap laptops are an essential input for Indian service sector businesses, including the IT sector, which is a major export earner. A licensing regime will hurt this sector's profitability directly.

Low-income Indians and small businesses benefit massively through cheaper imports. A licensing regime—even with exemptions—increases friction, incentivises corruption at customs entry and reduces overall welfare.

Nor is this policy likely to be effective in its stated aim. Protectionism, at best, leads to mediocre local production. With no international competition, local companies might be able to increase their domestic share but have no incentive to improve or compete in the international market. Moreover, given the current levels of manufacturing capabilities, companies will merely assemble laptops in India after importing sub-components from abroad, mostly China. If this Production by Licensing Imports takes off, it will only mean that imports from China will increase in the form of sub-components instead of finished goods.

This policy move allows us to step back and think about a more fundamental question: why have failed protectionist policies found a new lease of life now?

I suspect that this is an unintended consequence of anti-intellectualism. Here’s how.

The story began with the vilification of domain experts. Once total narrative control became the objective, every economist criticising a policy came to be discounted as a partisan. It’s one thing for Twitter trolls to challenge trade economists on import restrictions, and it’s another for a government to start believing its own bullshit that economic management can be done by ‘swadeshi’ partisan defenders.

The next step in the journey was to apply the label “strategic” to whole sectors in the wake of China’s aggressive rise in technology sectors. As RSJ has written in his post, it is ludicrous to identify whole sectors as strategic. For example, I have written earlier that not all semiconductors are strategic. Had that been the case, I am sure you would have heard a lot more about them before 2019.

Once this label “strategic” is applied liberally, the Overton Window stretches to encompass all sorts of crazy ideas, including the ones that have failed before. And because economists are no longer running the show, emotive phrases such as “national security risk” and “reduce import dependence” start carrying more weight than they should. Just as the witticism goes that “War is too important to be left to the generals”, so is the economy too important to be left to the partisan defenders.

And so, we are condemned to repeat the mistakes of the past unless we realise that being a nationalist isn’t a sufficient qualification for making sound policy decisions.

India Policy Watch #2: Confronting Trade-offs for Electronics Manufacturing Success

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

(This is an earlier version of an article that was first published in the China-India Brief brought out by the Centre on Asia and Globalisation (CAG) of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy)

The improving performance of electronics manufacturing has been a topic of intense policy interest in India. Electronics exports saw a spectacular growth of over 50 per cent in FY23, reaching $11 billion. Electronics are now India’s sixth largest merchandise export, overtaking readymade garments. Encouraged by these successes, the government is confident of achieving its target of $140 billion in electronics exports and 1 million new jobs by FY26.

This sector is now portrayed as a vindication of the Indian government’s flagship industrial policy instrument: Production-linked Incentives (PLI). Policy debates have primarily focused on the PLI’s design, effectiveness, and pitfalls. But the elephant in the room is the crucial role of Chinese companies in India’s electronics manufacturing story.

This article argues that achieving stated targets in electronics manufacturing requires a “re-coupling” between Indian and Chinese businesses on three dimensions: chips, investments, and talent. This argument is unsettling since a stated reason behind government intervention in this sector is a reduction of import dependence on China.

Chinese Chips

Chips (or Integrated Circuits) are India’s eighth-biggest import item by value. ICs are a core component in all electronics. For instance, chips comprise over 50% of the Bill of Materials of a smartphone.

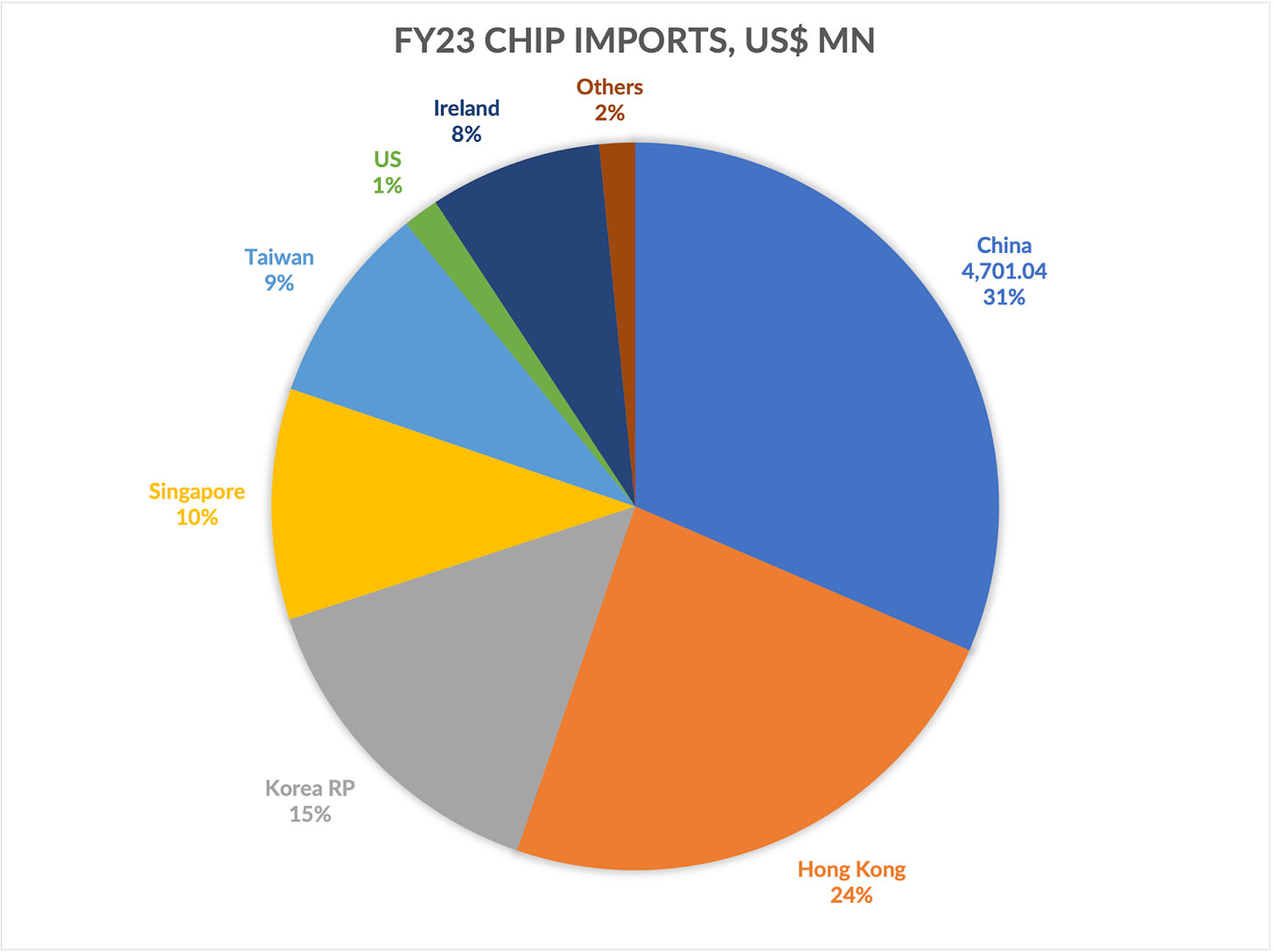

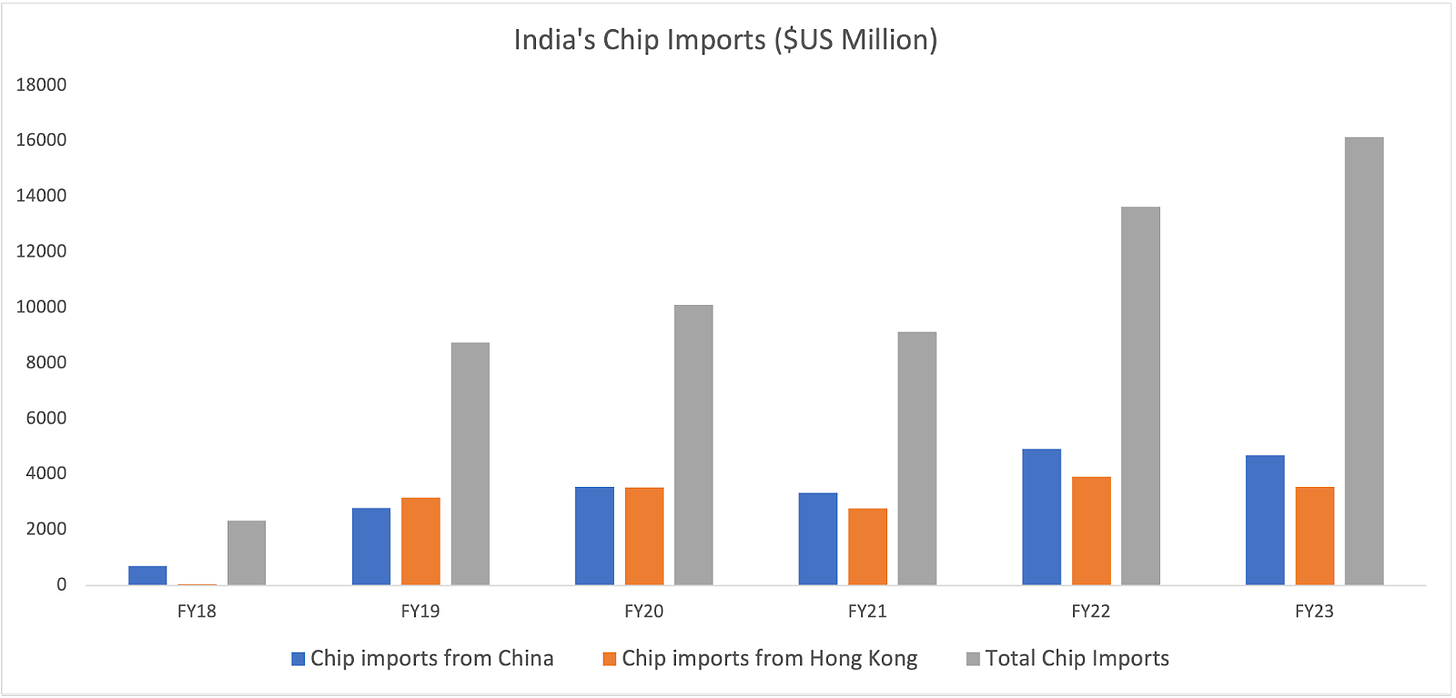

Figure 1 shows India’s overall chip imports from China.

Considering PRC and Hong Kong as one economic unit, India imported 55% of its ICs by value from China in FY23. Figure 2 plots the trajectory of chip imports over the last six years. Here again, the role of imported chips from China is evident.

India is importing many more chips from all countries, including from China. This trend indicates that more electronic device assembly is happening in India. A country will only import chips in large quantities if it has a downstream domestic equipment manufacturing ecosystem. As more Samsung, Apple, Dell or Redmi devices get assembled in India, chip imports to India will only rise further. Substantial import substitution through domestic chip manufacturing, even in the most optimistic scenario, will require a decade.

These figures sound alarm bells in strategic circles prompting tighter controls over imports from China. However, such measures are unnecessary and counterproductive for three reasons: one, chips imported from China are not necessarily Chinese chips. Likely, they are just tested, assembled, and packaged in China. Chip assembly is a labour-intensive process that is outsourced to other companies. China is a much bigger player in outsourced assembly and packaging of chips than in fabrication. So, it’s pretty likely that a die (an unpackaged chip) travels from Taiwan or Japan to China, gets packaged and finds its way into India. Moreover, even when chips are fabricated and packaged within China, a portion is done by foreign companies with facilities in China (such as Samsung, UMC, SK Hynix, etc.).

Two, chip dependence on China is not a strategic vulnerability. As long as multiple alternate suppliers are available outside China—which is the case for most commodity chips—the dependence fails to translate into a tool of statecraft that China can deploy against India.

Finally, for India’s own chip assembly and packaging to take off, a frictionless import of unpackaged chips without barriers is imperative. There is no avoiding imports of chips from China for the next several years.

Chinese Investments

Let’s turn to the significance of Chinese investments in Indian electronics manufacturing. In April 2020, the Indian government changed its Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) policy, making prior approval mandatory for foreign investments from India’s neighbouring countries. While there are understandable national security reasons, this decision negatively impacts the growth of electronics manufacturing as Chinese companies are crucial players in the ecosystem.

For instance, look at the Apple ecosystem, which alone accounts for over 50% of mobile exports from India. Apple contracts all its manufacturing. Of the 188 companies in its supplier list, 151 are Chinese or have a substantial manufacturing presence in China. The only way for Apple to shift a part of its supply chain to India is to get its Chinese suppliers to invest. But the FDI restrictions have thrown a spanner in the works. For instance, Apple’s plan to get BYD, its largest vendor, to assemble iPads, had to be dropped because of the Indian government’s decision to discourage Chinese investment.

Realising the fallout, the government made some concessions for Apple. It gave initial approval to twelve of its Chinese suppliers but on the condition that they would enter into joint ventures with Indian partners, and the latter would have a majority stake. However, this change hasn’t led to a rekindling of investor interest.

Similarly, Chinese mobile phone manufacturers in India have come under fire from the Indian government for not exporting enough and not having enough local suppliers. Their response is that the FDI restrictions make it difficult for them to bring in their Chinese component suppliers to set up shop in India.

Discouraging Chinese investments in this sector will only mean higher imports of components. Assemblers will pay back a major chunk of industrial policy incentives as import tariffs to the Indian government, without really improving their global competitiveness.

If India wants to occupy a central role in electronics manufacturing, it will have to reconsider its view on investments from China, at least in the non-strategic areas.

Chinese Talent

Chinese talent is another crucial element of the global electronics supply chain. After the Galwan Valley clashes, the Indian government has made it difficult for Chinese businessmen, academics, industry experts, and advocacy groups to obtain Indian visas. While this might be justifiable from a national security perspective, this move has adversely affected Taiwanese companies trying to scale up manufacturing operations in India. Here too, the Indian government will have to strike a balance between geopolitical concerns and its manufacturing ambitions.

Confronting Trade-offs

India’s predicament in electronics manufacturing reflects the complexity of this supply chain. It is challenging to indigenise all stages of electronics manufacturing. External dependencies for intermediate goods, specialised equipment, international talent, and critical materials will continue to remain even when the final product is made in India. And because China is a central node in the electronics manufacturing supply chain, de-coupling from these entities will be counterproductive for India’s manufacturing ambitions.

In this author’s view, the Indian government needs to make two shifts in its policy approach to China.

One, distinguish between the Chinese governments and Chinese businesses. Indeed, the Chinese Communist Party’s controlled economy means that Chinese businesses have less agency than their counterparts in the US or India. It is also true that China’s aggression on the border and adversarial positions at multinational fora show that it sees a growing India as a threat, not an opportunity. However, it is also important to note that Chinese businesses—especially suppliers to other multinationals—have different incentives than the CCP. Outside a narrowly defined set of strategic sectors such as defence and telecommunications equipment, investments by such businesses in India is a net positive.

Chinese investments can also give us foreign policy leverage. Economist Swaminathan Aiyar’s recommendation “massive foreign investment is a bigger risk for the foreigner than the investee country. So, let us attract as much Chinese investment as possible, since the main risk will be theirs, not ours.” needs deeper deliberation beyond simplistic binaries.

Two, the Indian strategic establishment needs a sharper definition of what constitutes “strategic”. It is insufficient and counterproductive to define entire sectors as strategic. Not all types of chips or LCDs are strategic. They cannot be used to harm an adversary. Dependence on China for these items does not make it a strategic vulnerability for India. If imported chips and Chinese investments into electronics assembly is what India needs to accelerate its journey, they accelerate, not impede India’s growth.

In sum, China’s success in manufacturing was possible because it harnessed Western companies, even though the two sides had major political differences. Though a shared, tense border complicates the India-China relationship, India must take a leaf out of China’s book and cautiously utilise Chinese products, investments, and talent to close the power gap.

India Policy Watch #3: “Of Magnitude and Littleness”

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

A news item from the Hindustan Times from a couple of weeks ago struck me. It reads:

Marathi-speaking residents in certain regions of Maharashtra are following the footsteps of Kannadigas residing in Kannada-dominated areas of Maharashtra and expressed their desire to merge with Karnataka. The decision comes in response to alleged negligence by the Maharashtra government in providing essential civic amenities and water resources to their localities, people close to the developments said.

Recently, approximately ten gram panchayats in Kaagal taluk, Kolhapur district, passed a unanimous resolution requesting their merger with Karnataka.

Apparently, this has happened before too. Maharashtrians in 14 villages on the Telangana border tried the same stunt in December last year.

At least 14 villages dotted on the border of Telangana demanded inclusion as they were ‘attracted’ to the development and welfare schemes..

These moves give a whole new meaning to the phrase “to vote with one’s feet”. While they are unlikely to succeed, such pressure tactics should become far more common than they currently are. That’s because these villagers are able to keep their parochial nativism aside and put forth their demands for better governance from the State instead.

Reorganising states on linguistic lines, perhaps, is one reason why India has managed to keep itself together. However, I also feel that it has had the unintended consequence that state governments can now project themselves as providers and defenders of cultural and linguistic ‘goods’ rather than perform the duty for which they exist—governance, law and order, public services, and the like.

Any group that threatens to walk out of the state due to a lack of basic services then gets seen as an affront to cultural pride. The arena shifts from governance and performance to pride and nativism. And allows our states to paper over their shoddy performance on public goods and basic services, even as they hold the moral high ground as the protectors of regional culture.

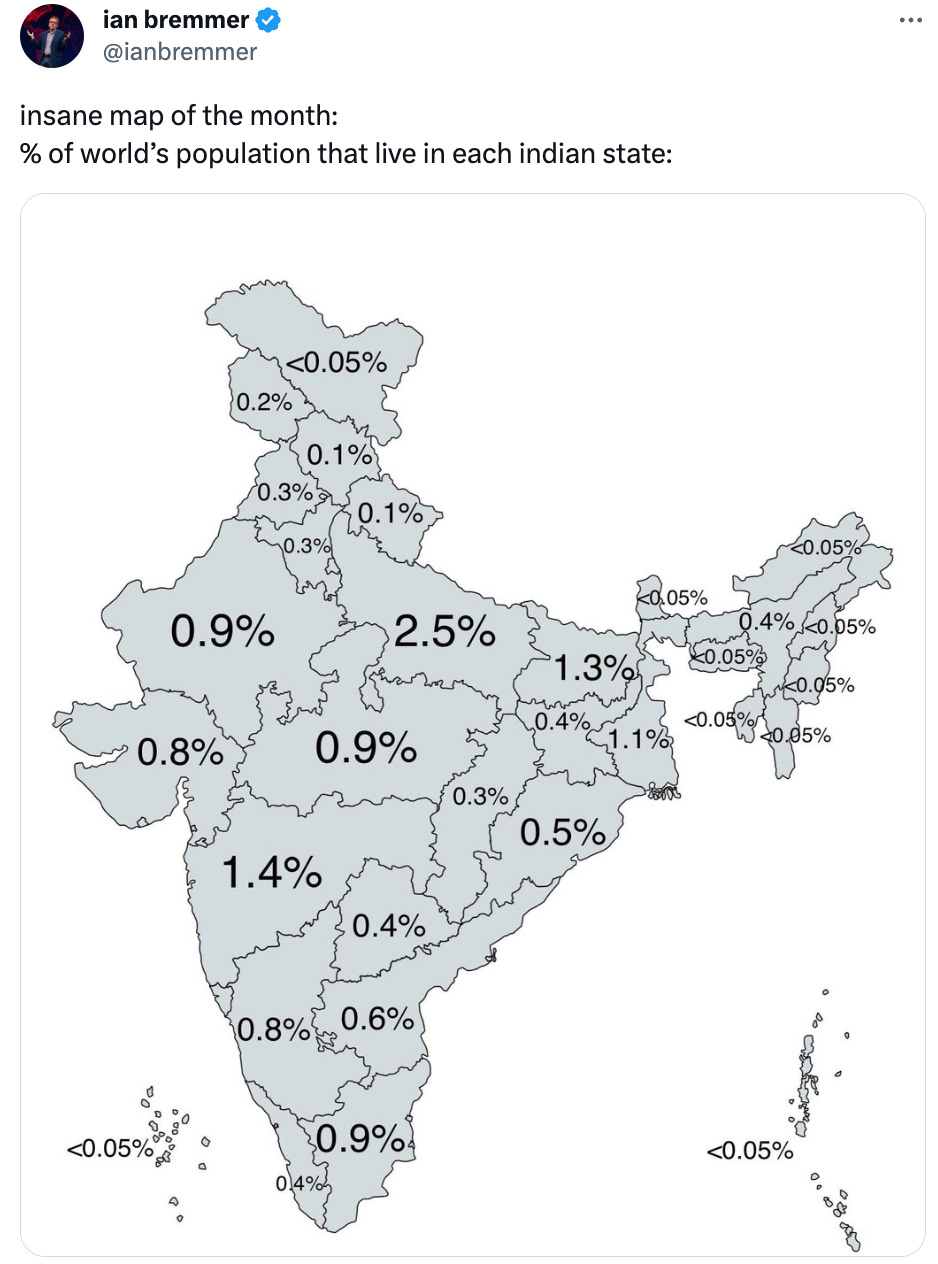

The other related insight that struck me last week comes from this tweet by Ian Bremmer.

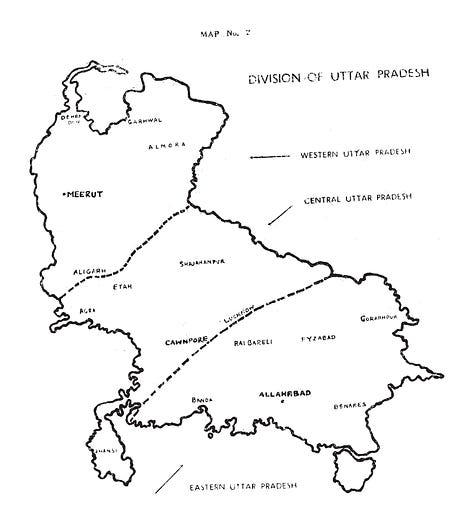

While the numbers aren’t surprising for any well-informed Indian, the policy-relevant insight from the image is that our states are way too big for preference discovery and good governance. UP, for example, is twice as populous as China's most populous province, Guangdong. There’s no way an Indian state government with current levels of capacity can provide for 2.5% of humanity. We probably need twice the number of states as we currently do.

And the good part is that this division can be done while keeping the established linguistic basis of states intact. In fact, Ambedkar had a brilliant proposal many decades ago in his book, Thoughts on Linguistic States. He made the critical distinction between “one language, one state” and “one state, one language” as the two bases for state creation. He wrote:

The formula one language, one State means that all people speaking one language should be brought under one Government irrespective of area, population and dissimilarity of conditions among the people speaking the language. This is the idea that underlies the agitation for a united Maharashtra with Bombay. This is an absurd formula and has no precedent for it. It must be abandoned. A people speaking one language may be cut up into many States as is done in other parts of the world…

All that one can think of is that the Commission has been under the impression that one language, one State is a categorical imperative from which there is no escape. As I have shown one language, one State can never be categorical imperative. In fact one State, one language should be the rule. And therefore people forming one language can divide themselves into many States.

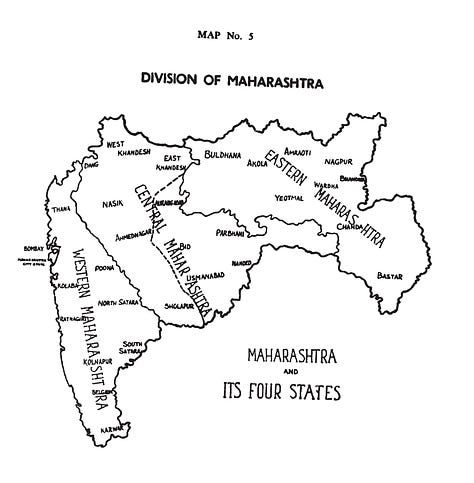

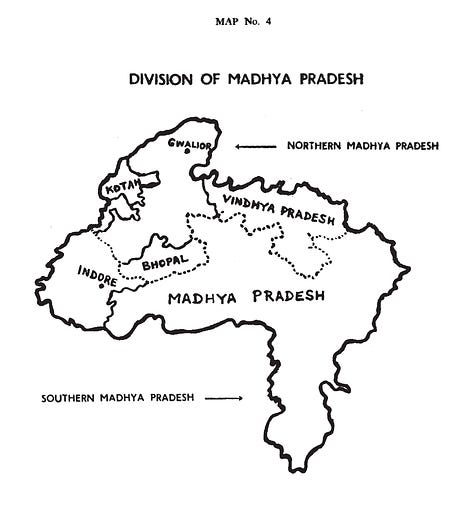

This prescient insight became a reality with the division of the two Telugu-speaking states in 2014. We need many more such states using the “one state, one language” principle. In fact, Ambedkar proposed some such divisions along with maps in his book.

More states and real local governments are necessary to extract the benefits of federalism in India.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] A Puliyabaazi on Applied Photonics and Science Research in India, ft. Sonali Dasgupta

[Policy Document] The Principal Scientific Advisor’s Office has released the National Deep Tech Startup Policy (NDTSP). It’s open for comments. Do read and suggest improvements.

To butcher Victor Hugo's quote: No force on earth can stop the revival of a dumb, failed idea if it sounds seductive enough.

Considering their pathological hatred for Nehru, it is surprising that BJP government going back to his economic model. Do they even realise this?