#232 As You Sow...

Of Fintech Messiahs, Subsidised Chipmaking, and India's Pakistan Strategy v2024.

Global Policy Watch #1: Crypto Chickens Have Come Home

Insights on global issues relevant to India

— RSJ

Around the same time last year, I read this Coindesk article by Ian Allison that started with this innocuous-looking paragraph:

“Billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried’s cryptocurrency empire is officially broken into two main parts: FTX (his exchange) and Alameda Research (his trading firm), both giants in their respective industries. But even though they are two separate businesses, the division breaks down in a key place: on Alameda’s balance sheet, according to a private financial document reviewed by CoinDesk. (It is conceivable the document represents just part of Alameda.)

That balance sheet is full of FTX – specifically, the FTT token issued by the exchange that grants holders a discount on trading fees on its marketplace. While there is nothing per se untoward or wrong about that, it shows Bankman-Fried’s trading giant Alameda rests on a foundation largely made up of a coin that a sister company invented, not an independent asset like a fiat currency or another crypto. The situation adds to evidence that the ties between FTX and Alameda are unusually close.”

That article triggered a train of events that concluded this week, almost a year later, when a New York jury deliberated for just under five hours to reach a guilty charge against Bankman-Fried for charges including wire fraud and conspiracy to commit securities fraud and money laundering. For all the promise of crypto changing the world of finance, its biggest player built a house of cards playing the oldest trick in the game. As the WSJ reports, these are precisely the words that the prosecutor used:

“The cryptocurrency industry might be new; players like Sam Bankman-Fried might be new. But this kind of fraud, this kind of corruption, is as old as time, and we have no patience for it,” U.S. Attorney Damian Williams said.

Bankman-Fried’s defence team tried to present him as a ‘math nerd’ who made a genuine mistake of delegating a tad too much without appreciating the risks building up in his empire. Unfortunately, that didn’t cut much ice with the prosecution because Bankman-Fried had done something more unusual when FTX was coming undone. He pretty much live-tweeted the collapse in keeping with his public persona of talking up his business and crypto. Continuing with the WSJ report:

But the most damaging testimony arguably came from Bankman-Fried himself. For the chance to tell his side of the story one final time, the disgraced crypto mogul sat through a gutting cross-examination by prosecutor Danielle Sassoon. She used Bankman-Fried’s own words, including from a whirlwind set of interviews he gave in the wake of his empire’s collapse, to expose what the prosecution described as a steady stream of lies.

During that questioning, Bankman-Fried claimed more than 140 times not to remember key details or his own statements, a fact that prosecutor Nicolas Roos noted in his closing argument on Wednesday.

“This was a pyramid of deceit built by the defendant on a foundation of lies and false promises, all to get money, and eventually it collapsed, leaving countless victims in its wake,” Roos said.

In prosecutors’ telling, Bankman-Fried presided over a straightforward fraud dressed up as a breakthrough financial innovation.

“It’s clear as day the defendant knows that they’re stealing and committing fraud. And that’s exactly what they do,” Roos said in his closing argument.

Well, that’s the way that story ends. Bankman-Fried now awaits his sentence and another trial in March next year for campaign financing fraud. Going by this trial, the writing is on the wall for him. So, all that’s left now is for all of us to do a post-mortem. And there will be many soon. Having followed crypto and its regulations for over two years on these pages, I have three points to make here.

First, unlike other fields, any major innovation in finance almost invariably involves a boom and bust cycle before a benign form evolves and gets adopted. It is the nature of the beast where those working in finance, and increasingly in its intersection with technology, find multiple interstices to find what’s called an ‘edge’ and upend the existing landscape. This can take the shape of something as ordinary as replacing human tellers who sit at a bank branch during working hours with an ATM that works all day, to offering mortgage loans to a subprime market and de-risking the portfolio in increasingly complicated ways. But like Minsky surmised, in the middle of every boom in financial markets lies the seed of an eventual bust. And once you sweep away the debris of the bust, the regulator arrives with new, prudential norms that tame the innovation and makes it work. But that one cycle of boom and bust is almost necessary because the information asymmetry inherent in financial market innovation—between the producer and consumer—is stark. Most regulators don’t understand it till it is too late.

Second, having said everything that I have said above, I still find what FTX and Bankman-Fried got away with quite extraordinary. I mean, here were a bunch of overgrown men and women playing with tens of billions of dollars of money using a Google spreadsheet to keep their accounts. Investment decisions were taken on Slack with emojis as responses. At what threshold of managing others’ money would any regulator step in to check whether that entity even has accounting software? I have tried hard to find out if any regulatory or statutory audit was ever done at FTX. It took a reporter at Coindesk to run through the flimsy balance sheet published by FTX and Alameda to see through the many inconsistencies. Wasn’t there even one regulator who could have considered looking at these balance sheets more closely when they started managing over $1 billion in assets? There’s no absence of mandate among those regulating the financial sector that prevented them from doing this. It brings me back to a point we often make here. We don’t need more regulations to prevent policy failures; we need rigorous enforcement of existing regulations. That’s good enough.

Lastly, over the last 7-8 years, I have seen charts that show how fintechs will eat away the margins and business of traditional banks one product at a time till banks reduce themselves to be mere providers of capital and risk. Every other lever of value will be taken away by these nimbler and savvier disruptors. Well, we are at the cusp of 2024 now, and I find most of these stories collapse under their weight - from BNPL to embedded finance to crypto. Maybe they will come back much chastened and eventually disrupt the industry. But like it has happened in finance from time immemorial, it will happen in slow motion. There’s more to finance than math geeks working out products on the fly and outwitting the counterparty. It is a lesson to be learned every time you see another unkempt manchild in shorts talking about probabilities, leverage, DeFi, and a new global financial order. He could be the messiah to herald a new age. However, empirical evidence suggests he could be someone who doesn’t know how to balance his books.

Global Policy Watch #2: Mutually Assured Decline — The Downsides of Subsidizing Chipmakers

Insights on global issues relevant to India

— Pranay Kotasthane with Jan-Peter Kleinhans

(An edited version of this article first appeared in Nikkei Asia a couple of weeks ago).

The UK released its National Semiconductor Strategy in May 2023. Given its comparatively small outlay of £1 billion, it was poo-poohed by news reports as lacking ambition and courage. Many reports claimed the UK stood no chance when stacked against tens of billions of subsidy packages from other governments, such as the United States, the European Union, Japan and India.

However, the UK is choosing a categorically different path based on utilising its comparative advantage. Most other countries are engaged in industrial policy escalation by heavily subsidizing domestic chip fabrication plants. They hope to become less dependent on East Asian juggernauts like TSMC and Samsung in the process.

While it seems to be a dominant approach, countries on the industrial policy escalation ladder are making some “leap of faith” assumptions that need deeper reflection. Here are four unappreciated second-order effects that these countries will be forced to reconcile sooner or later.

One: Dependence on East Asia will not go

Governments often cite national security concerns when justifying subsidies for front-end fabs. However, roughly 90 per cent of back-end manufacturing, the subsequent process step, is done in Asia, especially in Taiwan, China and Malaysia. The few announced back-end fab investments following the US CHIPS Act or EU Chips Act are unlikely to shift the needle on a global scale. This is even more true for the downstream production steps, such as printed circuit boards (electronic boards that hold all the different types of chips) and the final product assembly itself. Back-end manufacturing is labour-intensive with relatively low profit margins and low-value add, not amenable for production in the West. And from a national security perspective, back-end manufacturing, printed circuit board production and final assembly all provide opportunities for potential attackers to compromise the chip and/or final product. Countries need to invest in technical and regulatory solutions to screen malicious hardware, rather than attempt to re-engineer the entire supply chain.

Two: Counterproductive Domestic Production Requirements will Become Inevitable

Even subsidized, chips will be costlier to produce in the US and Europe: TSMC estimates that chips coming out of their new Arizona fab will be 30 per cent more expensive than the ones from Taiwan. The big question is, why would original equipment manufacturers (OEM) – companies building cars, smartphones, laptops, and so on – buy a costly chip from TSMC Arizona when they can buy the exact same chip at a lower price from TSMC Hsinchu?

If OEMs are hesitant to source domestically, governments might have to further intervene with local production requirements, just like the US government did with the Inflation Reduction Act. From a regulatory perspective, it would be relatively easy for a government to say that, for example, 20 per cent of chip content in an electric vehicle needs to be domestically sourced. However, implementing such a policy will add layers of complexity and costs to the already heavily intertwined global semiconductor value chain.

Three: Consumers pick up the tab

The immediate effect will be felt by consumers. If the OEM has to pay 30 per cent more per chip and faces local production requirements from governments, costs will be handed down to consumers. Of course, if the average price of an electric vehicle is around $60,000 and semiconductor content is around $1,300, higher semiconductor costs will not dramatically impact consumers. But the story is different for consumer electronics, where semiconductors account for a large chunk of the bill of materials, such as smartphones, laptops, gaming consoles, etc.

Four: Now is not Enough

The next concern is the inevitable evergreening of subsidies. The current belief is that once the fabs are up, they will keep churning chips, and the world will live happily ever after. That’s a tenuous assumption. Since small order sizes from militaries are unlikely to sustain domestic fabs, governments must rely on supporting commercial fab operators for longer-than-anticipated periods.

For instance, ASML estimates that by 2030, roughly 10 per cent of global capacity will not be based on market demand but was built out due to geopolitics driven by governments. Ten per cent higher capacity also means ten per cent less utilisation in the entire market. The lower the utilisation rate of a fab, the lower its profit. This creates even more incentives for fab owners to ask for continued government support.

A risky experiment

We are currently witnessing a comeback of industrial policy and governments’ understandable fascination with semiconductors as the backbone of our digital society and industry as a whole. But ultimately, chips are a mere input, and a lot will depend on whether OEMs agree with governments that capital efficiency can and must be sacrificed to gain resilience through geographic diversification. That is a big ask. Despite the rhetoric, it is improbable that OEMs will say goodbye to “just in time” and embrace and pay for “just in case”.

The renaissance of industrial policy might give a temporary boost to the industry. Nonetheless, some fabs will die the slow but inevitable death of under-utilisation after cashing in hefty government subsidies. Governments have chosen a costly path with little consideration for the second-order effects on consumers and businesses.

The UK government’s approach of focusing narrowly on some segments of the supply chain where it has a comparative advantage offers an alternative way of thinking. Its emphasis on international cooperation to ensure the security of supply seems a more sensible approach than engaging in a subsidy race. This would have seemed obvious a couple of years ago. But such is the force of geopolitics that it has become an outlier. Yet, it deserves serious consideration.

Matsyanyaaya: What Should India’s Pakistan Strategy v2024 Look Like?

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

I spent the weekend co-organising an academic conference as part of Takshashila’s Network for the Advanced Study of Pakistan Fellowship. The fellowship builds high-quality research scholarship on Pakistan in India by connecting bright researchers with top-notch scholars of Pakistan’s foreign policy, economy, and society.

One question came up at various points during the conversations. What should India’s Pakistan strategy be? With Nawaz Sharif back in Pakistan, is a post-election period for both countries in 2024 the right moment to improve relations with each other?

Here’s my current thinking on this question.

The current foreign policy stance of treating Pakistan as a distraction rather than a prime focus area serves India well, albeit with some changes.

Now, of course, most people agree that a somewhat normal India-Pakistan relations is a leverage point for both nation-states. A large subset of this group also believes that India should not start another round of talks because it is bound to fail like all attempts in the recent past. Any such move would inevitably invite a violent response from the Pakistani military-jihadi complex, they argue, and hence, it’s better to let the situation be as it currently is. I broadly agree with this policy prescription but not the reasoning.

My reasoning is as follows: India benefits far more from having China—and not Pakistan—as its main rival. Focusing on a larger, richer, and more advanced adversary makes Indian policymakers think of “levelling up” rather than “punching down”. Countering China as a mission statement makes India focus on national power across all its dimensions — technological, economic, and military. In contrast, a focus on Pakistan makes Indian policymakers narrowly focus on counter-terrorism and conventional military power.

There are finer details, of course. The pre-eminence of the “China threat” often makes Indian policymakers commit self-harming moves such as import restrictions and app bans. But a pre-eminent “Pakistan threat” amplifies the bigotry in our society, a far-worse malaise. Public policy is often about choosing the second-best option.

There’s another important caveat here. Defocusing Pakistan should not be allowed to turn into a disparagement of Pakistan or Pakistanis. As the Israel-Hamas story has confirmed yet again, the “enemy always gets a vote on your strategy”. In other words, however weak the adversary might be, it always has the agency to throw your plans off-balance. Hence, it is essential not to push the adversary into a corner by humiliating it in a way that makes it retaliate with nothing to lose.

In the India-Pakistan context, a ‘defocus but not disparage’ strategy would mean things like not denying visas to Pakistanis by default (as was the case during the Cricket World Cup), resuming trade links cautiously, and dumping batshit crazy ideas such as taking over PoK or withdrawing from the Indus Water Treaty into the dustbin.

Israel’s response to the Hamas terrorist attack also took my mind back to the 26/11 Mumbai attacks. The Indian government back then would have been under tremendous domestic pressure to retaliate. And yet, it demonstrated restraint. The Indian side didn’t allow Pakistan to dominate its strategic vision. While India chose to play the long game, Pakistan was demonstrably proven as the terrorist hotspot that it was. The next decade and a half were terrible for Pakistan. By the time the 2016 surgical strikes happened, the power gap between India and Pakistan had increased substantially. When India responded to Pakistan’s provocation using surgical strikes, the other nation-states were firmly in its corner. In a way, the restraint in 2008 made the 2016 surgical strikes and the 2019 Balakot airstrikes viable options.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] Check out this Puliyabaazi with author-illustrator Nikhil Gulati on his excellent graphic novel, The People of the Indus.

[Report] Measuring National Power in the Postindustrial Age is an educative read for anyone interested in international relations. The report was released by RAND in 2000, but its insights remain relevant.

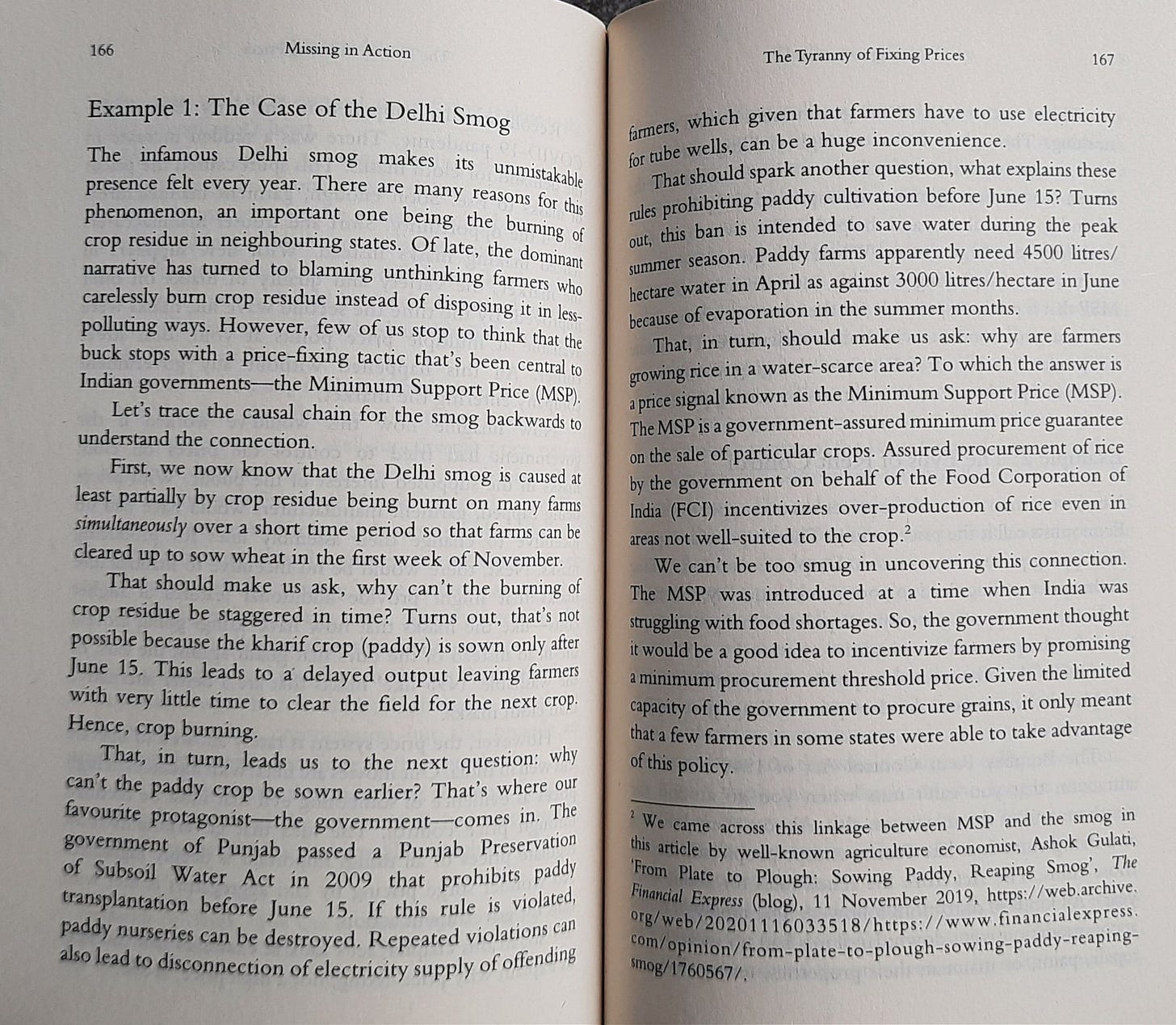

[Post] The Delhi Smog is back in the news and lungs. We highlighted the link between crop MSP and smog in our book, Missing in Action. Here’s a screenshot.

I thought I will never sully this pious place with my comments but my word, what a crackling post on sbf.

If I had a chocolate every time I heard the declaration about the demise of banks…

Lastly, RSJ, noone has seen you and SBF in the same room. Just saying.