This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PS: If you enjoy listening instead of reading, we have this edition available as an audio narration courtesy the good folks at Ad-Auris. If you have any feedback, please send it to us.

India Policy Watch: Disinvestment — Aakhir Kyun?

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

On October 30th came the news that the government has modified bidding parameters to make the Air India disinvestment lucrative for buyers. Essentially, the government first made the sale difficult by inserting way too many conditions. Unsurprisingly, it found no buyers. Then hit COVID-19 and now the government is so desperate to raise resources that it is willing to finally remove the self-placed hurdles.

This got me thinking: what are the different narratives regarding the purpose of disinvestment? What stories do they tell and what policy actions do they imply?

I could think of three such narratives.

Narrative #1: Governments Should Sell Businesses it Can’t Run Well

The underlying story is simple: some PSUs incur consistent losses. Losses indicate that the government cannot run them well. Hence, these PSUs must be sold. The focus in this narrative is on numbers such as falling market caps to decide on companies to be sold. For example, the argument that Air India Makes a Loss of Over ₹ 20 Crore Per Day has repeatedly (and successfully) been used to rationalise Air India’s sale. The policy position implied (and unsaid) in this narrative is that it is okay for governments to run businesses as long as they are profitable. What’s also implicitly implied is that the sale of a government-run company first requires running it down into an incorrigible loss-making entity.

Narrative #2: Governments Can Raise Revenue by Selling Some Assets

The underlying story is one of urgency. Governments need money. One way they can make money is by selling the assets they own. Hence, divestment. Governments find this narrative quite useful. Every budget, the government sets a disinvestment target for itself with the aim of reducing its fiscal deficit.

The focus on a revenue target from disinvestment can lead to perverse incentives: when it can’t find genuine buyers, government coaxes government-run companies like LIC to purchase government-run companies on sale. This ‘sale’ shows up as revenue in the government accounts even though the government’s stake has not reduced in reality.

Narrative #3: Governments Should Sell What’s not-Strategic

In some sectors, markets might underproduce even though that sector is non-substitutable and vitally important to the nation-state. In such sectors, the government should continue to run businesses, regardless of the revenue a sale can generate or the losses made in running that business. Examples could be oil, rare-earth exploration or extremely critical defence equipment. Outside this reduced set, the government should sell all businesses. The focus in this narrative is on the reduction of overall government equity in non-strategic sectors, and not as much on the revenues raised by the sale of government assets.

A Battle of Narratives

Narratives 1 and 2 have enjoyed dominance in Indian policy discourse at various times. When the economy was chugging along, narrative #1 dominated: many PSUs were to be first put in a state of coma to enable an eventual sale in the distant future. Now, with almost a decade of poor economic growth, the revenue maximisation narrative has become more salient.

The third narrative is still on a weak footing. What's strategic and what’s not? What’s the marginal cost of public funds used for running a PSU? These questions rarely feature prominently in disinvestment discussions.

India Policy Watch: Growth, Liberty And Freedom

— RSJ

We have often argued for economic growth as a moral imperative for India. This opinion divides people. And we understand that. We get the usual questions thrown back to us. Should the pursuit of material wealth be such priority for any society? More so for one like ours where issues of equity, liberty and political rights aren’t yet settled; where there’s a chasm of everyday despair between the promise of our constitution and the reality that confronts us.

The pat response to this kind of argument is twofold. One, we (and others like us) make a point that growth is a precondition to solve these issues. Redistribution requires something tangible than mere lofty ideals to share with others. Putting it ahead of growth is putting the proverbial cart before the horse. Second, we can’t escape the trade-offs between growth and other social welfare objectives for our current stage of economic development. Of course, we must avoid the mistakes of other developed nations in our path to prosperity. But it will be futile to mimic policy actions they are taking now and apply them to our context while getting to where they are now. We have to bias our actions to achieve growth at the cost of other objectives. Else, we will achieve neither. This is the old Rostow (1960) ‘stage’ of development argument.

Sen’s Arguments

The philosophical challenge to this view comes from what we may term the Amartya Sen school of developmental economics. Sen has argued with passion about the need to invest in social infrastructure (education and health) that will build human capabilities across society. This is the only way to sustain growth. Like Sen once wrote:

“I know of no example of unhealthy, uneducated labour producing memorable growth rates.”

In other words, in Sen’s worldview people like us who prioritise growth are putting the cart before the horse. This debate can go on and on. As it has.

However, over the last few weeks, as I was reading Sen’s Development As Freedom (1999), I realised he has made more nuanced arguments on this than what my reductive reading of him has been so far. I haven’t read a lot of later day Sen and my views were informed by his interviews and columns in media since he started batting for an entitlement driven state-run programmes during the time of UPA-1. The book makes a strong case for freedom and views liberty from the perspective of a welfare state. I shook my head in disagreement often but far fewer times than I had anticipated. I nodded way more than I ever thought I would.

Freedom And Human Capability

As the name of the book suggests, Sen argues freedom is both the core objective and the primary means of development. Sen’s definition is wide and encompasses five types of freedoms that are distinct but related. These include political freedom, economic facilities, social opportunities, transparency guarantees and security. Like classical libertarians and enlightenment thinkers, Sen’s focus is the individual. He views individual freedom along the five vectors as the primary variable that determines their effectiveness and success. Compromising on any of these freedoms for economic growth cannot be considered a good outcome regardless of what the per capita income data might show. It will hurt in the long run.

Sen defines a ‘capability approach’ to freedom where he concerns himself with the individual’s ‘capability to lead the kind of lives we (they) have reason to value’. This freedom and this human capability when raised consistently is a net positive – it increases our choices, our wellbeing, our options to improve the society which should eventually lead to economic growth.

Sen supports markets, individual liberty and responsibility, and economic freedom as the factors that enable the increase in human capability. Social institutions and infrastructure should be built to support these especially in countries with low per capita income and a large workforce. The focus should be broader than enhancing mere human capital that views an individual as a means of production. Instead, a human capability frame sees the individual beyond being an agent for the production of goods and services. It takes a holistic view of what they could be.

The Need For Entitlement

This is where his focus on entitlement emerges. For him, an individual is poor when they are denied any of the five types of freedom he has outlined. This happens either because of path dependence or the nature of the state where they live. Either way, this has to be corrected and true freedom ‘to lead the lives they have reason to value’ should be an entitlement of every citizen.

The kind of thinkers Sen rounds up to make a case for freedom – Adam Smith, Montesquieu, Hayek – surprised me on one hand. After all, these aren’t the names you usually associate with him. On the other hand, it is difficult to make a case for individual and liberty without bringing these names into the discussion. Sen, as he came across to me through this book, is a believer in capitalism and the power of individual freedom to create value for the society. These attributes are important for what they produce but he also insists they are good even without being instrumental for growth.

Freedom is good. Period. That it also leads to growth, makes it better.

Benjamin Constant On Liberty Of Moderns

The book reminded me of the famous speech of Benjamin Constant, The Liberty of Ancients Compared with that of Moderns (1819). Constant used the word ‘commerce’ to broadly speak about economic growth. There were two insights in his speech about commerce and liberty that can be considered as precursors to Sen’s books.

First, he believed commerce is the perfect antidote to the arbitrary use of powers by the state. Essentially, economic growth leads to freedom which is one half of Sen’s argument. To use Constant’s words:

“But commerce also makes the action of arbitrary power easier to elude, because it changes the nature of property, which becomes, in virtue of this change, almost impossible to seize.

Commerce confers a new quality on property, circulation. Without circulation, property is merely a usufruct; political authority can always affect usufruct, because it can prevent its enjoyment; but circulation creates an invisible and invincible obstacle to the actions of social power.

The effects of commerce extend even further: not only does it emancipate individuals, but, by creating credit, it places authority itself in a position of dependence. Money, says a French writer, 'is the most dangerous weapon of despotism; yet it is at the same time its most powerful restraint; credit is subject to opinion; force is useless; money hides itself or flees; all the operations of the state are suspended'. Credit did not have the same influence amongst the ancients; their governments were stronger than individuals, while in our time individuals are stronger than the political powers. Wealth is a power which is more readily available in all circumstances, more readily applicable to all interests, and consequently more real and better obeyed. Power threatens; wealth rewards: one eludes power by deceiving it; to obtain the favors of wealth one must serve it: the latter is therefore bound to win.”

“… Commerce has brought nations closer, it has given them customs and habits which are almost identical; the heads of states may be enemies: the peoples are compatriots. Let power therefore resign itself: we must have liberty and we shall have it.”

The Danger of Trading Off Liberty For Growth

The other argument Constant makes is the danger of people getting immersed in individual pursuits and enjoyment that they easily cede their right to political power and transparency. This is what Sen would call sacrificing a few vectors of his definition of freedom for economic growth. The idea of a benevolent dictator who will curb some freedom but set things right that seduces many educated, well-off Indians. Constant warns:

“The danger of modern liberty is that, absorbed in the enjoyment of our private independence, and in the pursuit of our particular interests, we should surrender our right to share in political power too easily. The holders of authority are only too anxious to encourage us to do so. They are so ready to spare us all sort of troubles, except those of obeying and paying! They will say to us: what, in the end, is the aim of your efforts, the motive of your labors, the object of all your hopes? Is it not happiness? Well, leave this happiness to us and we shall give it to you. No, Sirs, we must not leave it to them. No matter how touching such a tender commitment may be, let us ask the authorities to keep within their limits. Let them confine themselves to being just. We shall assume the responsibility of being happy for ourselves.”

I will conclude with Constant’s final words on this which mirror those of Sen’s. And they are similar to what we have advocated when we have made a case for economic growth and liberty over the past year on these pages.

“The work of the legislator is not complete when he has simply brought peace to the people. Even when the people are satisfied, there is much left to do. Institutions must achieve the moral education of the citizens. By respecting their individual rights, securing their independence, refraining from troubling their work, they must nevertheless consecrate their influence over public affairs, call them to contribute by their votes to the exercise of power, grant them a right of control and supervision by expressing their opinions; and, by forming them through practice for these elevated functions, give them both the desire and the right to discharge these.”

Trivia: WLFPR in Bangladesh

Interesting facts and stats relevant to public policy

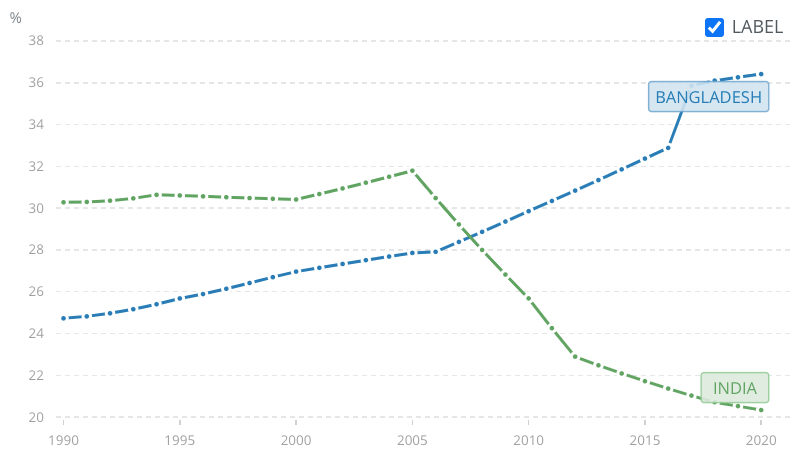

The Women Labour Force Participation Rate in neighbouring Bangladesh increased by nine percentage points in the last 15 years. India’s decreased by 11 percentage points in the same period.

Graph and Data: World Bank

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article]: Bhagwati in the Mint on Why Amartya Sen Is Wrong

[Article]: A summary by the Outlook on Sen and Bhagwati arguing on the pages of the Economist

[Report]: On Bangladesh’s U-curve bending performance on Women Labour Force Participation.

[Article]: An excellent data story on the five paths of disinvestment in India by Sudipto Banerjee, Renuka Sane and Srishti Sharma.

[Podcast]: On Puliyabaazi, Pranay and Saurabh learn about the history of banking in India from Amol Agrawal.

Share this post