This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PS: If you enjoy listening instead of reading, we have this edition available as an audio narration courtesy the good folks at Ad-Auris. If you have any feedback, please send it to us.

India Policy Watch: The Indian State — Too Big or Too Small?

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

In edition #23, we tried to answer this question: how to think about the Indian state? Closely related is another question: is the Indian State too big or too small? And as it holds true for many other phenomena in India, the answer is both.

I’m sure most readers of this newsletter feel that the Indian state is bloated, overbearing, and huge. Is that really the case? Let’s look at four important parameters.

Size Measured by Government Expenditure: Relatively Small

A government has three instruments at its disposal in any policy issue-area: produce, finance, and regulate. All three instruments require government expenditure. So, one way to judge government size is to measure public expenditure as a proportion of overall economic activity. The higher this parameter, the bigger the government.

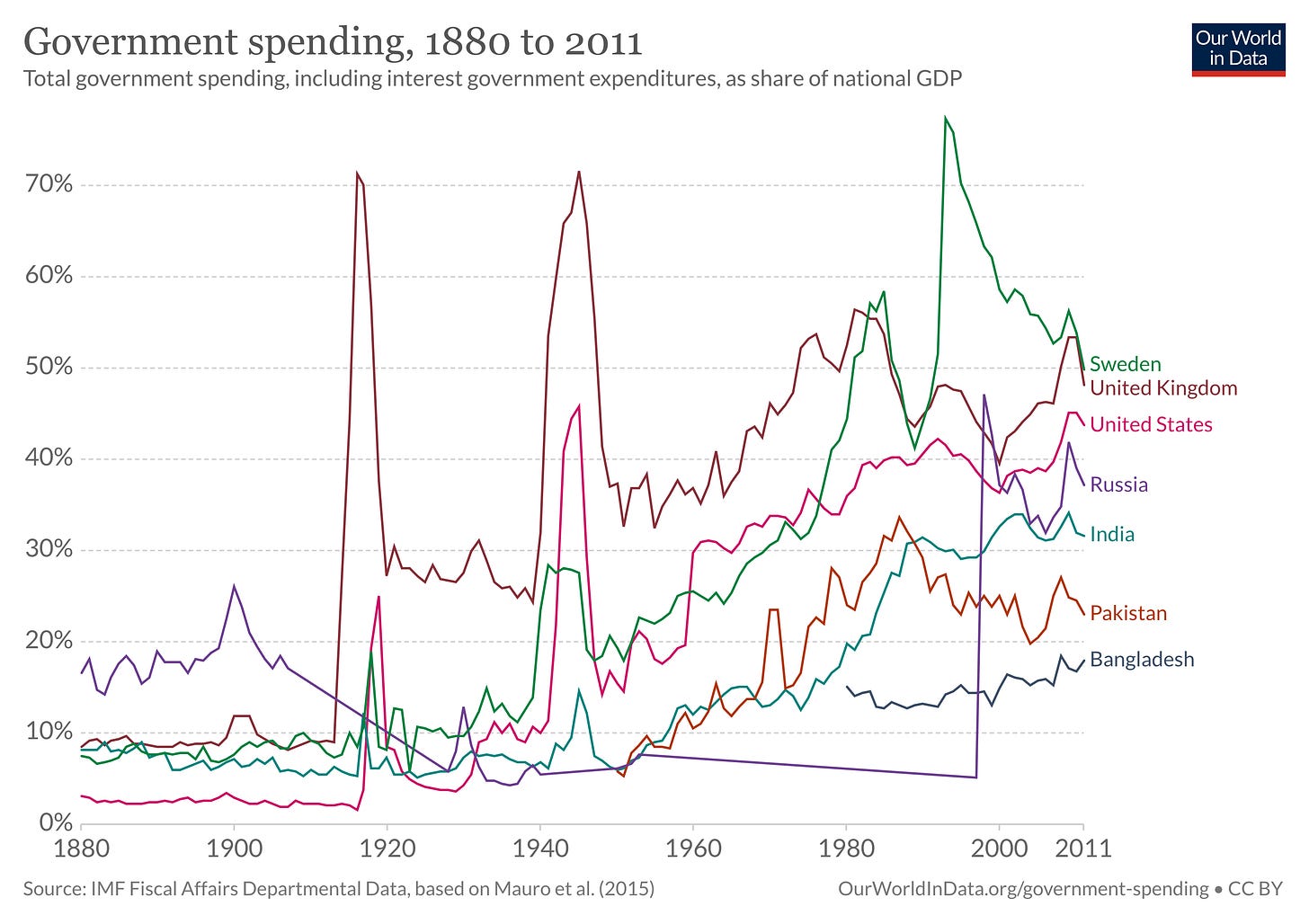

In 2018, India’s overall public expenditure as a proportion of its GDP stood at 27%. The US was at ~38%; Russia was at ~36% GDP; Sweden was at ~49%, and Pakistan was at ~21%. Clearly, the Indian state is no outlier on this measure. Have a look at how some selected countries at disparate levels of economic strength stack up.

Essentially, this parameter has been steadily rising for most countries across the world, ever since the welfare state became mainstream. Moreover, there is a strong correlation between government spending and income levels — the richer a country, the higher the government’s expenditure as can be seen in the chart below. This is known as Wagner’s Law in public finance literature.

Note the US government expenditure. The common perception is that because it is a capitalist country, the government would have a smaller role to play in the economy. That’s clearly not the case when measured on this parameter. As the country got richer, there were even higher demands to fulfil on health, education, defence, and infrastructure. Coming back to India, as a low-middle income country, its public spending is relatively small as well. Clearly, the Indian state isn’t at the commanding heights of our economy.

Size Measured by Government Employees: Small

Another caricature of the Indian state is a bloated, overstaffed organisation with a large number of employees. But the Indian state is relatively small on this parameter too. Here are some stats making this point from Devesh Kapur’s must-read paper Why Does the Indian State Both Fail and Succeed?:

“In the early 1990s, the global average of government employment as a percent of population was 4.7 percent. In countries of Asia, it was 2.6 percent. In India, it was 2 percent .. Core elements of the Indian state—police, judges, and tax bureaucracy—are among the smallest of the G-20 countries. Indeed, while the absolute size of government employment peaked in the mid-1990s, in relative terms, the decline in size of central and local governments began much earlier.”

“A comparison between the size of the civilian workforce of the federal govern- ment in India with that of the United States is instructive. Remember, India has a large number of public enterprises and public sector banks that are under the central government. Even so, the size of the Indian federal government is half the size of its US counterpart when normalized by population: specifically, the US federal government had 8.07 civilian employees per 1,000 US population in 2014, down from 10.4 in 1995, while India’s central government had 4.51 civilian employees per 1,000 population, down from 8.47 in 1995.”

Even on this parameter, the Indian state is a relatively small one.

Size Measured by Competence: Too Small

Nothing counterintuitive here. The Indian state lacks competence in fixing the most basic market failures, from law and order to public health and education. The competence gap has only widened over the years as many bright Indians now have the option of taking up a job outside the government, even outside India, with changing times.

Size Measured by Ambition: Too Big

This is really where the Indian state is overbearing. The aspiration of the Indian state has no bounds. Right from the outset in 1947, the Indian state sought to transform colonial India economically, politically, and socially. This revolutionary DNA meant that the Indian state set itself ambitious goals regardless of the capacity to achieve them. Over the decades, new goals were appended to this lofty project.

What Does All This Mean?

So the Indian state is big as measured by its own ambitions. Unsurprisingly, it continues to own airlines and soap factories. As an ambitious democratic entity, it also seeks to frame regulations and laws to constrain virtually every private initiative in every issue-area. The paradox is that on all other parameters, the state is quite small, neither having the capacity to enforce rules nor the ability to anticipate the consequences of policies beforehand.

Devesh Kapur writes that this “precocious” nature of the Indian state has also skewed what Indians expect from their governments in three ways:

“One, precocious democracy tends to militate against the provision of public goods in favor of redistribution. Countries that experienced economic development prior to the transition to democracy also tend to adopt democratic institutions that constrain the confiscatory power of the ruling elite. However, when countries pursue democracy prior to economic development, the democratic institutions adopted enhance the redistributive powers of the state.”

“Second, a precocious democracy with electoral mobilization along social cleav- ages favors creation of narrow club goods. A central puzzle concerning the poor provision of basic public services in India is seemingly weak demand in an other- wise flourishing electoral democracy.”

“Third, an imperfect democracy with noncredible politicians will tend to emphasize the provision of goods that are visible and can be provided quickly, like infrastructure, over long-term investments, like human capital or environmental quality.”

Resolving this high ambition versus low capacity paradox is central to improving governance in India. It must choose to do fewer, more important things, and build capacity to do them well. Trade-offs are inevitable.

India Policy Watch: Factions and Liberal Democracy

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

There’s much handwringing on how fractious the US society has become over the years. The next few months don’t look good. The dangerous speech Trump made at White House yesterday peppered with lies and conspiracy theories that undermined the engine that keeps democracy going – election – is only the beginning. Even if Trump fails to mount a legal challenge, he has convinced enough right-thinking Americans (and a lot of Indians going by social media) that elections can be rigged in America.

This isn’t a genie you can put back into the bottle.

Shifting Sands Of Factions

What’s worse in the US right now is that no one can be sure about the traditional definition of factions anymore. Fractiousness works when you know your faction is distinct and different from the other. But that’s not so easy to claim in the US. If Trump’s domestic policies could be loosely labelled racist, buoyed by white supremacists, what explains the higher votes he polled across all minority groups including Blacks and Muslims this election over last? If California is the home of Bernie bros, capital of wokeness and full of bleeding heart liberals, how do you square that with the population voting in favour of proposition 22? That vote will continue to keep drivers of Uber and Lyft and other gig workers classified as independent contractors with the freedom to set their own hours but not receiving protections like minimum wage, health insurance or overtime. What explains the Republicans gaining seats in the House and almost retaining the Senate with probably the most inept President at the helm. Or the race being so close despite Trump’s lack of any redeeming feature. Had it not been for the pandemic that revealed how shambolic his administration was, he would have won by a landslide.

Factions Can Be Good

So, the factions aren’t homogenous anymore based on traditional parameters on which they were defined – race, identity or common passions or interests whose origins could be religion, shared experiences or class. There’s some other realignment of factions happening here which will need a deeper study. Be that as it may, the idea of factions in a liberal democracy is actually a feature and not a bug. The notion of competing groups of passions or interests that counteract each other instead of coalescing into a majority that dominates the regime is good for democracy.

This is why there’s a view that coalition governments have better track records of reforms and governance in India. Or that the consolidation of Hindu vote with the BJP that obliterated the caste, region or language factionalism so dominant in the past three decades might actually be bad for India. In that sense, this dead heat of a presidential race might put the US in a better place as a democracy than the almost absence of factions that India’s polity is turning out to be in recent times. So long as there are institutions that can make the factions come together and get them to work, the US doesn’t have lots to worry.

Madison On Factions

Aristotle in Politics had a suggestion for how to manage the extremes of oligarchy and democracy in a society. He advocates a mixed regime that combines the elements of both. He writes:

“Where the middling element is great, factional conflict and splits over the nature of regimes occur least of all.”

So, the question is what’s the best way to have factions in a society and yet not be consumed by its internecine wars of passions and interests? How do we ‘manage’ the factions because it is clear we can’t stop it. This question brings me to the Federalist Papers (#10) written by James Madison (1787).

Madison writes:

“By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: the one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects.”

Madison soon establishes that removing the causes that create factions will mean trampling on the liberty of people and is fraught with terrible unintended consequences. So, he soon focuses his efforts on managing the effects:

“The inference to which we are brought is, that the cause of faction cannot be removed, and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects.”

“If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote. It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the Constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government, on the other hand, enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good and private rights against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is then the great object to which our inquiries are directed. Let me add that it is the great desideratum by which this form of government can be rescued from the opprobrium under which it has so long labored, and be recommended to the esteem and adoption of mankind.”

“By what means is this object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same time must be prevented, or the majority, having such coexistent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression. If the impulse and the opportunity be suffered to coincide, we well know that neither moral nor religious motives can be relied on as an adequate control. They are not found to be such on the injustice and violence of individuals, and lose their efficacy in proportion to the number combined together, that is, in proportion as their efficacy becomes needful.”

Madison is quite prescient about the need for a greater variety of parties to control the overzealous efforts of a single faction that seeks to flame passions. He writes:

“Hence, it clearly appears, that the same advantage which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic,–is enjoyed by the Union over the States composing it. Does the advantage consist in the substitution of representatives whose enlightened views and virtuous sentiments render them superior to local prejudices and schemes of injustice? It will not be denied that the representation of the Union will be most likely to possess these requisite endowments. Does it consist in the greater security afforded by a greater variety of parties, against the event of any one party being able to outnumber and oppress the rest? In an equal degree does the increased variety of parties comprised within the Union, increase this security.

…The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States. A religious sect may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the Confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it must secure the national councils against any danger from that source. A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the Union than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire State.

In the extent and proper structure of the Union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government.”

In essence, factions are natural in a democracy and it is the republic that controls the effects of factions by restricting its spread to the Union. India hasn’t got credible political factions at the union but the factions in the states still offer hope of the state being taken over by a single party. The exit polls from Bihar (if they hold) continue to showcase this natural release valve of a liberal democracy.

A Framework a Week: Seven Stages of the Policy Pipeline

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

This week’s framework comes from Vijay Kelkar and Ajay Shah’s In Service of the Republic. They argue that the ideal public policy process comprises these seven stages:

“Stage 1: the establishment of the statistical system. Facts need to be systematically captured. Without facts, the entire downstream process breaks down.

Stage 2: descriptive and causal research. This requires a research community which will study the data, establish broad facts and regularities, and explore causal connections.

Stage 3: the creative phase of inventing and proposing new policy solutions. A large menu of choices needs to be at hand, for possible policy pathways.

Stage 4: public debate where rival solutions compete with each other. This requires a vigorous process of debate and discussion, in writing and in seminars. A broad consensus needs to come about on what will work, within the analytical community. In the Indian context, this is often assisted by the expert committee process. The purpose of the expert committee process is to sift through an array of possible policy pathways that are in the fray at the end of stage 3, and filter down to a few which make sense.

Stage 5: the internal government process of decision making. This is where ministers and senior bureaucrats take stock of the range of possible policy pathways and make decisions. This is the zone of political economy, and the creative trade-offs that make progress possible.

Stage 6: the translation of the decisions into legal instruments. Most policy decisions must be implemented through law that is enacted by the legislature, or subordinate legislation in the form of rules or regulations. High technical quality, and subtle detail, of this drafting process is of great importance.

Stage 7: the construction of state capacity, in the form of administrative structures that enforce the law.”

— Kelkar, Vijay; Shah, Ajay. In Service of the Republic . Penguin Random House India Private Limited. Kindle Edition.

The most fascinating takeaway from this framework is that for better policy outcomes, capacity needs to be developed in all seven stages. For instance:

“A field is in poor shape on stages 1, 2 and 3 if we are not able to envision ten wise persons who can usefully be members of an important expert committee (at stage 4).”

This framework also explains why crises can produce terrible policies in the name of reforms. In difficult times, the willingness to do something is higher. But if there’s underinvestment in the early stages of the pipeline, crises can fast-track poor policies as well. A recent example of a poorly thought-out policy fructifying in the backdrop of a crisis is the Harayana government’s policy to reserve private-sector jobs for locals. As they further write:

“the possibilities in a crisis are the product of previous work that has been done in the early stages of the pipeline, and the human capabilities for stages 5, 6 and 7 that have been built ahead of time. The apparently high marginal product of crisis is partly grounded in misattribution; a lot of the credit has to go to the investments by the policy community of previous years. When we see the correlation between crisis and reforms, we are exaggerating the role of the runner who carries the baton across the finish line.”

This framework is a useful tool for thinking about effecting policy change in the Indian context.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Video]: From Yale Open Courses, Prof Smith on Aristotle’s idea of polity to keep factions in check and how it presages Madison’s Paper 10.

[Paper]: A useful guide to reading social science papers. Money quote: “Very few articles in a field are so important that every word needs to be read carefully. It's okay to skim and move on.

[Article]: Marc Levinson’s latest on containers and mega-ships.

[Report]: A detailed account of cesses & surcharges by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Tip: both terms, though often used interchangeably, are quite different. The similarity is that both are evil.

Share this post