#10 Do Robin Hood Taxes Work?

Who becomes a Terrorist?, US-Pakistan Relations, and Violent Protests

PolicyWTF: Progressive Taxation Is Not so Progressive

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

Redistribution has long been seen as one of the objectives of tax policy. The guiding idea was that by changing tax rates alone, one can reduce income inequalities. This vision led to highly progressive personal income tax regimes combined with high corporate taxes not just in India but in countries such as US and UK as well. I didn’t know that in these countries, marginal income tax rates were set at over 90 per cent immediately after the Second World War and in the US, a tax rate of over 90 per cent existed even until 1963 (Rao & Rao)!

India wasn’t to be left behind. The paper linked above says:

The tax policy was central to the task of bringing about a socialistic pattern of society, and in 1973-74, the personal income tax had eleven tax slabs with rates monotonically rising from 10 percent to 85 percent. When the surcharge of 15 percent was taken into account, the highest marginal rate for persons above Rs. 0.2 million income was 97.5 percent.

So, did such highly progressive tax regimes work? A paper investigated this question in Chile which had a similar tax system. Surprise, surprise, it didn’t work there. Essentially, the authors measured inequality (using Gini coefficients) without and with a highly progressive tax distribution. The Gini coefficient actually increased when the progressive tax was applied. To understand how exactly, read the paper.

But the main lesson for us is this:

Redistribution should be one of the goals of the expenditure side of the budget. Raising revenues shouldn’t be tasked with this goal at all. Broadening the base, lowering the tax rates for all individuals and companies, and getting rid of tax exemptions is more progressive than a highly progressive taxation.

Ending this with the key insight from the Chilean experience on taxation:

The main implication.. is that tax structure should be chosen on the basis of tax collection and efficiency criteria, and not according to its redistributive merits. Distributional considerations should enter only when deciding the overall tax burden. Once the amount to be redistributed is decided, revenue should be raised with the most efficient taxes and income inequality should be ameliorated through expenditures.

A Framework a Week: Terrorism, Poverty, & Education

Tools for thinking about public policy

“Who becomes a terrorist?” is a question often discussed. Commonsense answers to this question are that poverty, lack of education, and ideology prepare the ground for becoming a terrorist. But this paper by Alexander Lee (h/t Varun Ramachandra) proposes a different framework. See the graph below. It suggests that below a socioeconomic threshold, terrorism actually becomes less-likely. The explanation being:

below a set socioeconomic threshold, individuals have little chance of participation due to their inferior access to political information, disposable time, and politically salient social contacts.

Image source: A. Lee (2011)

Instead,

the politically involved are likely to be relatively wealthy and well educated because they have access to political information and can afford to devote time and energy to political involvement. Within this subgroup, the higher opportunity costs of violence for rich individuals will lead them to avoid it. The members of violent groups will thus tend to be lower-status individuals from the educated and politicized section of the population.

This predicts that as a society becomes more prosperous, a larger share of its population is likely to be politically involved, including in the use of terror.

Matsyanyaaya

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

This week saw a minor reset in US-Pakistan ties with the Trump administration approving the resumption of Pakistan's participation in a coveted U.S. military training & educational programme more than a year after it was suspended.

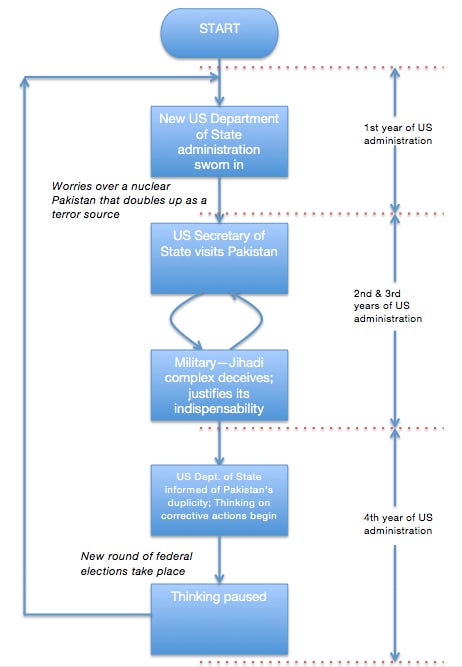

This backstep reminded me of the former US Ambassador to India Robert Blackwill's frustration over US policy towards Pakistan. He pinned the blame on the lack of continuity between successive administrations on taking tough steps against Pakistan. His argument can be summarised in this flowchart:

This time around, Pakistani military-jihadi complex has proved its importance to the US in Afghanistan. Though the heady days of US-Pakistan bonhomie are still not quite back, the Pakistani military-jihadi complex continues to assert its geostrategic importance.

India Policy Watch

Insights on burning policy issues in India

For once, my Google Scholar Alert worked! It sent me this paper on the day many Indian cities witnessed non-violent and violent protests in opposition to the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019: Hunger to Violence: Explaining the Violent Escalation of Nonviolent Demonstrations.

“Under what conditions does a non-violent protest become violent?” is the question that this paper seeks to answer. Specifically, it considers the impact of three factors — food price increases, unemployment rate, and whether a demonstration is organised or spontaneous — on the nature of the protest.

The last factor was of interest to me given that spontaneity characterises protests of radically networked communities. The paper finds evidence for the argument that spontaneous, leaderless protests are more likely to turn violent. The reasons are:

Spontaneous collective action does not have a guaranteed duration or frequency. As a result of the uncertain qualities of unplanned demonstrations, individuals are more likely to perceive that the collective action is unsustainable. Spontaneous nonviolent demonstrations also face a higher risk of group collapse because no leaders exist to bear significant collective action costs. Thus, in the face of a seemingly temporary window of influence, individuals are more apt escalate to violence as a last resort.

This paper hasn’t analysed the impact of government repression on the nature of the protest. For the way ahead for the current protests in India, look at this tweet thread by Bilal Baloch, who predicts that one should expect further suppression of the protestors and their sympathisers. :(

For now, these three results are quite interesting by themselves:

Higher food prices may necessitate a switch to violent tactics because the need for nutrition must be immediately resolved.

When the unemployment rate within a country is high, individuals will face increased difficulties in providing for themselves and their families. As a result, they will be more likely to try any possible tactic, including violent ones, to coerce change.

The confluence of high food prices and a high unemployment rate creates an environment in which violent escalation is most likely.

Organised demonstrations indicate that leaders have borne the costs of collective action, signaling the sustainability of nonviolent action. Conversely, the duration of spontaneous protests is highly uncertain and may cause demonstrators to consider a switch to violent tactics before the collective action collapses.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

“Measurement can be a remarkably effective tool for social change.” Tyler Cowen lists some influential indices and talks about indices that should be made.

[Podcast] Philip Tetlock's episode on EconTalk on how to resist outcome-irrelevant learning.

RAND has a new report out on the US Department of Defence's posture for AI.

A good read on trade-offs in decision-making.

That’s all for the week, folks. Read and share. 再见 👋