Hey all, our little newsletter hits a 150 with this edition! That’s about 600,000+ words. We also completed two years of bringing you Anticipating The Unintended last month. The process has been rewarding for us (heh, what else can we say about a free newsletter, really?). We hope it’s been of use to you. Thank you for your attention and time. We will be grateful to hear from you.

India Policy Watch #1: Two Indias

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

In the old debate between growth versus equality, we have consistently batted for growth in the Indian context. Like we have written earlier (“What Drives Rapid Economic Growth”), economic growth is a moral imperative for policymaking in India. Other things, like equality, climate impact or anything else, are important but if you have to make the trade-offs like it is inevitable in policymaking, you should accord a higher priority to growth over them. This doesn’t endear us to many. How can you not think of carbon emissions, sustainability or the planet for future generations, they ask? Our point remains simple. You need to prioritise when you have limited resources and a thin state capacity. There are millions of great causes to serve in this world but the state cannot be expected to solve all of them. Falling for such demands that are more appropriate for an economy more advanced than India will distract us from our core objective - lifting millions of Indians out of poverty. And trust us, if you don’t do this, you won’t achieve any of the other exalted goals too. In the three decades since the reforms of 1991, we have achieved more on this objective than the previous four. Maybe in the process, we have got a few more billionaires in India. It shouldn’t matter so long as competition is free and individual liberty is sacrosanct. Those should be the only limiting conditions for acting on growth.

Doubt

But there are weeks when I question this. This is one of those weeks. You see, the underlying assumption in our argument is that there should be growth. Not just any growth. But one that’s sustainable with expectations of trickle-down benefits. So, when the latest GDP print for the quarter ended September 2021 came out last week, it made me pause. The GDP grew at 8.4 per cent over the same period last year and it is likely (unless a third wave hits us) if this trend continues, we might see double-digit full-year growth. The usual chest-thumping about being the world's fastest-growing economy followed soon after. However, parsing the GDP data a bit more and also taking a broader view of the macroeconomy might be useful in appreciating what kind of growth we are seeing here.

The real GDP at ₹35.7 lakh crores is about 0.33 per cent higher than the period ended September 2019. That is we have lost two years of growth in the pandemic. And remember, we were already slowing down considerably at this time two years ago. So, it wasn’t a great base, to begin with. But this isn’t all. A significant part of this growth has been contributed by government spending in public administration and defence which grew by over 17 per cent. The capital spending by the union government this year is up almost 25 per cent over the last year. Private consumption which has been a significant driver of the Indian economy over the last two decades is still below pandemic levels. So are other sectors like construction, travel, hospitality and logistics that employ the bulk of semi and low skilled labour. There are a few bright spots but with caveats. Agriculture grew at a healthy rate of 4.5 per cent but it is likely the rural spending power is getting negated by the rise in inflation. The recovery has been good so far but it isn’t as robust as in the US and China who recovered to pre-pandemic levels earlier than India by a few quarters. The US is expected to grow at 6 per cent while China will likely end up with 8 per cent growth this year on their kind of GDP base. On the other hand, the GST collections continue to be at over Rs 1.2 lakh crores and growing at a steady clip of over 25 per cent. The direct collections are expected to beat the annual target of Rs. 11 lakh crores. That apart, the companies belonging to the Nifty 50 index have seen record profits in H1 of this fiscal.

How does one reconcile the almost no growth scenario of the last two years and the lower than pre-pandemic levels of consumption with the record tax collections and profits?

The Voiceless Informal Economy

One reason is possibly better tax compliance because of digitisation and surveillance tools now available that make evasion difficult. The other and more compelling reason is the formalisation of the economy. The pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on the informal economy who struggled to cope with frequent lockdowns, lack of migrant labour to run their establishments and health risks of the pandemic. You perhaps bought your vegetables and fruits from a stall in the local market earlier. The lockdown meant neither of you could transact. You then shifted to an online vendor who delivers it to your doorsteps in less than ten minutes. And you never went back to your older routine. The earlier transactions of this kind were mostly going below the radar. Now they are captured as part of the formal economy and show up in GST numbers. But what about that vegetable vendor? They have lost their livelihood. And this isn’t just an isolated instance. A large shift to the formal economy has happened across sectors among the consuming class. This has hit the informal economy hard. No wonder the labour participation rates at this moment are the lowest in over a decade. We had seen a similar trend in GDP right after the initial shock of demonetisation where the formal economy which gets measured easily and more frequently showed robust growth while the drag of the informal economy showed up later. This time around the pain in the informal economy could be worse. The GDP growth and record GST collections and corporate profits must be seen in this light. The overall pie might have shrunk while the formal economy part has grown. This might not be the growth of the moral imperative kind that we argue for here.

Monetary Policy FTW

The other point to consider is the monetary policy India has followed through the pandemic. The fiscal space was constrained even before the pandemic. All the ‘₹20 lakh crores package’ grandstanding aside, it was clear that barring the free food provided from the central PDS and a few other sops, there wasn’t much fiscal support coming from the union government. The heavy lifting was done by the RBI and its skillful management of the monetary policy. RBI has maintained price stability and supported small and medium enterprises through a loan moratorium which gave them a much-needed breather during lockdowns. It continued to keep liquidity high in the system to support credit offtake with added incentives and loan guarantees given to financial institutions to support the most impacted and vulnerable sectors and households. This is all good but this masks the impact of loose monetary policies followed by central banks all over the world including India. Central banks have purchased sovereign and corporate bonds in record quantities over the past few years. This went on overdrive during the pandemic. The buying of these longer-term assets benefit the higher-income households more. The simultaneous loosening of monetary policies around the world has created asset price bubbles all over.

In India, these assets are held disproportionately by the same 30-40 million wealthy, high consuming class households that drive most of the public opinion in India. The benefits of such policies to the remaining Indians who don’t participate in the bond or equity markets and keep most of their wealth in safe havens like savings or fixed deposits is minimal. Also, as we come out of the pandemic, the same class of wealthy households have the opportunity to use the low yield regimes to diversify away from financial markets into real estate, crypto and other assets provided to them by wealth advisory firms. There are two Indias here. The other India has hardly any access to these and continues to wonder what those CoinSwitch Kuber ads during IPL are all about. This is setting the stage for deepening inequality over future decades. Importantly, as the Omicron threat starts to become real, any possibility of tightening of monetary policy, reeling back of Quantitative Easing (QE), ending net asset purchases and likely control of inflation through rate hikes have receded. This means the gravy train of easy money for investors and intermediaries will continue for the foreseeable future.

Fiscal Stimulus For The Few

Lastly, there’s a lot that’s been made about the fundraising by Indian startups during this year. The numbers bear this out. In the first nine months of this year, startups (mostly B2C) raised about $25 billion of funding, about 90 per cent of which was from investors outside India. To put this in perspective, in the six years before, the total funding was about $50 billion put together. The large consumer class that’s going digital rapidly, the enterprising spirit of founders and the availability of tech talent are driving this unprecedented surge in investments. Also, China seems to have closed its doors for now with its ham-fisted clamp down on its national digital champions. Apart from startups, there has been a further inflow of about $30 billion of global liquidity looking for returns into Indian markets and companies during the year. This inflow that’s about 2 per cent of GDP, some argue, is like a fiscal stimulus to the Indian economy. According to this logic, the government didn’t loosen its purse strings to stimulate the economy; instead, it made it attractive for foreign funds to invest directly. Quite clever, eh?

There are two problems with this. First, this is a hugely convenient post facto logic. Nobody could have predicted this inflow at the start of the year, nor could anyone have foretold China’s bizarre moves on its digital economy. Second, even if this were a kind of fiscal stimulus, it is different from what a government stimulus would have been. The B2C startups burn their cash in three ways. One, they use it for customer acquisition. This is the money spent on discounts, cashbacks, in high decibel advertising during cricket matches or on digital marketing when they are looking for blitz scaling their business. Quite simply, this money goes as a stimulus to the same 30-40 million wealthy, mostly urban households that have smartphones, transact on these B2C platforms and watch these programmes. A family of a driver or of a cleaning lady isn’t using the Zomato Gold discount coupon. Two, the startups invest in the infrastructure needed to scale up. This means spending on their tech platforms. Most of these startups tend to be asset-light. They don’t have plants and production lines where any additional investment has a multiplier effect. Their money is spent on cloud service providers and IT infrastructure and hardware companies. Three, they spend it on hiring people and investing in their capabilities. This is largely tech talent where the demand right now outstrips supply. This has meant war for talent and a sharp rise in the salaries of good quality programmers for the same kind of roles they were previously doing. The ongoing merry-go-round of ‘great resignation’ has meant no real change in deepening the talent pool in India. It is the same set of people who are already in that upper tier moving across companies demanding higher wages. Anecdotal evidence suggests average salaries have gone up by 30-50 per cent for those in the ₹10-30 lakhs band. Of course, there is some ancillary hiring of drivers, delivery boys (always boys) and other temporary jobs going on but that’s not where the real money is being spent. So, yes, this is a kind of stimulus but it is meant for the same lot that’s already benefiting from the formalisation of the economy and loose monetary policy. It is a triple whammy for them.

Sometime during the pandemic, it was clear that we were seeing a K shaped recovery. We wrote about it in a few past editions (here and here). The trend has only exacerbated globally and more so in India. While there’s a widespread sense of strong recovery among the opinion-making classes that are benefitting from this triple whammy, it is difficult to see how the other India is benefiting from it. The lopsided impact of the pandemic on the education of students from poorer families in government schools is another worry. A couple of academic years have been lost for families that have no access to devices for their children and online content from their school. In the long term, this will worsen inequality.

I don’t think politicians are unaware of this. The repeal of farm laws, the extension of the free food grains scheme and the queering of the pitch on ‘cultural’ issues in the run-up to UP elections suggest that the BJP is aware of the hardships in that other India. Good politicians always have their ears to the ground. The well-fed, working from home, smug class can be easily swayed by the narrative wars on Twitter and Whatsapp with fake photographs of airports and bridges from China and South Korea passing off as India. But it is difficult to do the same to those whose prospects have materially diminished in the past two years. They will call out the propaganda. It is that India now that’s being wooed in the UP elections. And it will remain the focus of this government till 2024. The real solution lies in a genuine commitment to reforms and free markets. That, as we have seen, is difficult. So, we will be left with a strange mix of India Shining and majoritarianism as means to show progress and win over voters. That kind of growth cannot be our moral imperative.

Matsyanyaaya: A Thank You Note to Xi Dada

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

"Choose your enemies carefully, 'cause they will define you.."

Thus went a U2 song. In the strategic realm, Pakistan was long the primary adversary that defined India and vice versa. This hyphenation had a foundational impact on India’s strategic approach. The centre of gravity of our armed forces moved to India's northwest. All three strike corps of the Indian army were created to execute a land grab as a bargaining chip, should Pakistan misbehave. Over time, the military was also made responsible for preventing Pakistan-sponsored terrorism in J&K.

Nevertheless, a small and weak primary adversary, one that kept becoming smaller and weaker over time, meant that India was able to wing it. All it needed to do was be better than Pakistan, which was not much of an ask. Arguments for modernising armed forces, collaborating with the US, or building a stronger navy, failed to move the needle because none of them was essential to tackle the adversary.

Today, things appear quite different. Pakistan is no longer the adversary that defines India. It continues to remain an irritant, but not the reference point. At the level of serious discourse, I've seen this shift using my own extremely unscientific methodology. I maintain a Pakistan Mention Time (PMT) for discussions. PMT is defined as the time elapsed since the start of a discussion on India's geopolitics until Pakistan first makes an appearance. Until about four years ago, PMT was dangerously low; Pakistan often came up within the first ten minutes of a discussion and like a good Bollywood villain, its shadow loomed large throughout the discussion. That has changed sharply over the last four years. The PMT has increased significantly. Pakistan does make an appearance in most discussions but only briefly. More like Bob Christo, less like Amrish Puri.

Quite clearly, Pakistan has been displaced by China as the primary adversary in our minds and actions. And India has no option but to punch up to a bigger, more-powerful adversary rather than punch down to a much-weaker one. The strategic establishment knows that we just can't wing it this time around. Consequently, structural changes such as a deeper collaboration with the US and other Quad countries, a shift of the centre of gravity from the northwest to the north, and integration of the various force elements, is happening at a much faster pace.

And of course, the credit for all this goes to Xi Dada and the PRC's international conduct. PRC has made it a point to antagonise many of its neighbours. Its stance has made reconciliation difficult and reignited old conflicts to a point of no return.

Disengagement with the PRC hurts India more. But increasingly, India has no choice but to absorb the costs by collaborating with other countries. The old notion of keeping equal distance from the major powers seems untenable, even foolish. The strategic challenge before India has never been more clear. The game is on.

But as India navigates the China challenge, there's a critical point that needs to be internalised. That there's a difference between being defined by your adversary and becoming like your adversary.

While India was hyphenated with Pakistan for most of its independent history, it managed to not be like Pakistan quite well. The difference between a secular democratic republic and a rabidly religious, majoritarian, military-jihadi-complex-run country couldn't have been starker. But that difference is fast narrowing. Unfortunately, we have become a bit like our adversary on some counts. Religion has become a primary domain of State action and majoritarianism has weakened the Republic like never before. Thus, an important element of responding to the PRC has to be to avoid becoming like the PRC. As it takes centre-stage in our national imagination as the primary adversary, the tendency to become like it will keep growing stronger. Keeping the society above the individual, prioritising stability over freedom, and elevating one-party, one-leader above everything else, will start to seem attractive propositions. That's precisely what we have to be wary of. The ideology of the PRC can’t be defeated by becoming like it. Instead, PRC can only be defeated by rejecting China's hierarchical worldview. As the famous Marcus Aurelius quote goes - "the best revenge is not to be like your enemy".

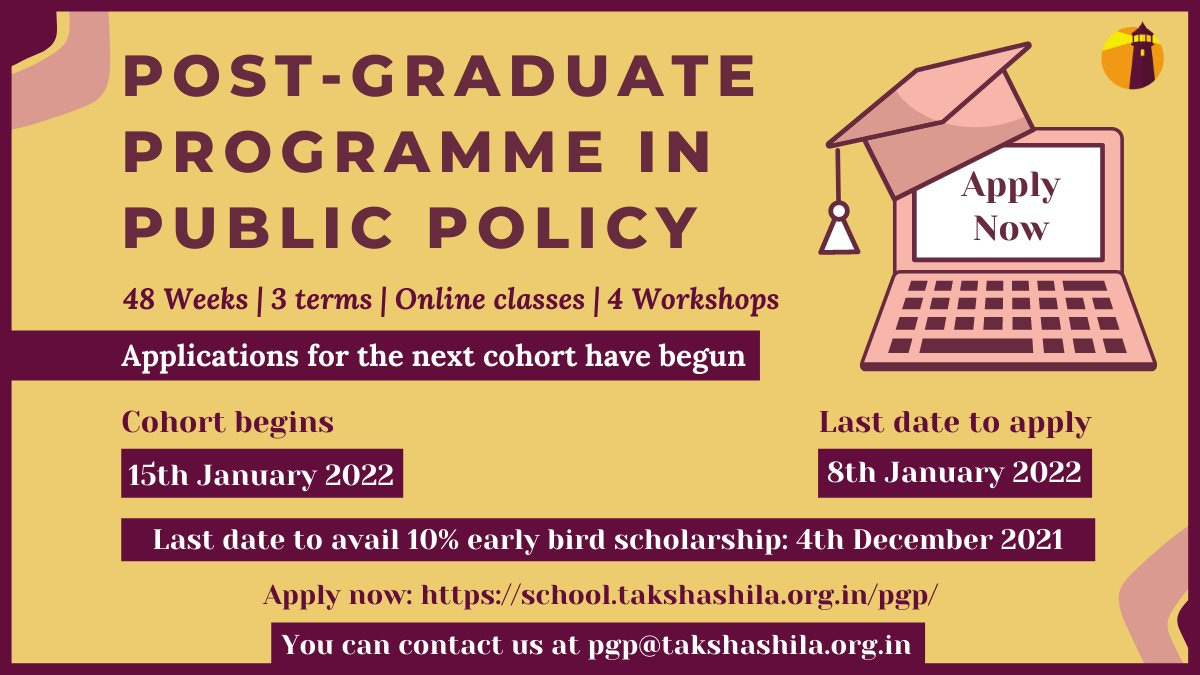

If you find the content here useful, consider taking a deep dive into the world of public policy. Takshashila’s PGP — a 48-week certificate course will allow you to learn public policy analysis from the best practitioners, academics, and teachers. And that too, while you continue to work. In other words, the opportunity costs are low and the benefits are life-changing. Do check out.

PolicyWTF: Auto-debit Cancel Culture

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Pranay Kotasthane

By now, RBI’s new rules on auto-debit of recurring payments have fried my brain and I’m sure yours too. Whether it’s the phone bill or online digital subscriptions, these rules have added friction to even the most trivial payments. Not just individuals, smaller knowledge-based organisations that rely on digital subscriptions need to sacrifice a good chunk of one person’s workday every month to manually purchase email software, team communication software, and e-paper subscriptions. And that’s just the demand side. On the supply side, companies that rely on product subscriptions are suffering from a drop in revenues due to declined transactions.

To understand the details of the issue, take a look at this comprehensive note by our friend Anupam Manur. In short, some consumers were not able to exit from subscription cycles easily. Some were auto-subscribed to lifelong subscriptions they couldn’t cancel. Then there was the ever-present issue of fakesters stealing people’s money - all three genuine issues requiring better consumer protection enforcement by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food, and Public Distribution by punishing wrongdoers.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, the RBI asked banks, card companies and merchants to register e-mandates. These organisations in turn simply declined existing mandates. The RBI could well have fined the banks and card companies until they did not register the e-mandates. Instead, it chose a blunt instrument hurting every consumer using an auto-debit facility.

RBI’s intentions aside, this move is symptomatic of what I call hyper-multiobjective optimisation — the bane of policymaking in India. One institution tries to perform so many functions that it does neither of them well. This is particularly the case with agencies that are relatively better. They soon start using their powers in other domains, regardless of their purpose. And thus, the courts make executive decisions, the executive short-circuits the legislature, and the RBI becomes a consumer protection forum.

India Policy Watch #2: Friedman on India

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

It amazes me that in the early years of the republic when the planning mindset was at its peak, the Indian government invited leading experts from other countries to comment on India’s governance choices. It seems unimaginable in today’s times that the Indian state was so open to ideas from outside.

Anyway, as part of that exercise, Milton Friedman visited India twice in the 1950s and wrote two stunning articles on “Indian Economic Planning” and “A Memorandum to the Government of India 1955”. Some ideas from these two articles continue to remain relevant today. I’m annotating them below for your reading.

What struck me was that Friedman was largely optimistic about India’s prospects at a time when the world thought India was destined to fail and Indians were destined to die from hunger. He put India’s human power in perspective through these words:

“Most people everywhere are simply hewers of wood and drawers of water. But their hewing of wood and drawing of water is made far more productive by the activities of the minority of industrial and commercial innovators and the much larger but still tiny minority of imitators. And there is no doubt that India has an adequate supply of potential entrepreneurs, both innovators and imitators.”

“In any economy, the major source of productive power is not machinery, equipment, buildings and other physical capital; it is the productive capacity of the human beings who compose the society. Yet what we call investment refers only to expenditures on physical capital; expenditures that improve the productive capacity of human beings are generally left entirely out of account. In the United States, for example, only about one-fifth of the total income is return to physical capital, four- fifths to human capital …. Destroy the physical plant of the United States and leave the skills of the people and it would take but a few years to restore the initial position. Destroy the skills and leave the plant and the level of output would sink irretrievably. The cathedrals of medieval Europe, the pyramids of Egypt, the monuments of the Moghul Empire in India are all testimony to the possibility of a high rate of investment in physical capital without a growth in the standard of living of the masses of the people. These considerations are especially important for India, precisely because its frontier is the frontier of technical knowledge and skill.

He then links India’s policies of protecting public sector enterprises with wastage of human power as follows:

“India’s basic problem is the inefficient use of manpower; it is no solution to protect inefficiency, and the attempt to do so leads to a waste not only of human resources but also of physical capital. The extra money consumers have to pay for the products, let alone direct subsidies to producers could be channelled at least in part into investment.”

His insight on where the Indian planning approach goes wrong is quite nuanced:

“Planning” does not by itself have any very specific content. It can refer to a wide range of arrangements: to a largely laissez-faire society, in which individuals plan the use of their own resources and government’s role is limited to preserving law and order, enforcing private contracts, and constructing public works; to the recent French policy of mixing exhortation, prediction, and cooperative guesstimating ; to centralized control by a totalitarian government of the details of economic activity. Along still different dimension, Mark Spade (Nigel Balchin), in his wonderful book on How to Run a Bassoon Factory and Business defined the difference between a planned and an unplanned business in a way that often seems letter-perfect for India. “In an unplanned business”, he writes, “things just happen, i.e. they crop up. Life is full of unforeseen happenings and circumstances over which you have no control. On the other hand: In a planned business things still happen and crop up and so on, but you know exactly what would have been the state of affairs if they hadn’t”.

In India, planning has come to have a very specific meaning, one that is patterned largely on the Russian model. It has meant a sequence of five-year plans, each attempting to specify the allocation of investment expenditures and productive capacity to different lines of activity, with great emphasis being placed on the expansion of the so-called “heavy” or “basic” industries. A Planning Commission in New Delhi is charged with drawing up the plans and supervising their implementation. There is some decentralization to the separate states but the general idea is centralized governmental control of the allocation of physical resources.

He predicted that the Indian way of planning ignored time dynamics, and was doomed to fail for this reason.

“So-called plans are laid out long in advance and it is exceedingly difficult to modify them as circumstances change. Inevitable and necessary bureaucratic procedures mean that the right hand does not know what the left hand is doing, that a long process of files going up the channels of communication and then coming back down is involved in adjusting to changing circumstances.”

Of course, the Indian government’s obsession with exchange rate management caught his attention. There’s a long section on why overvaluation of the currency is counterproductive.

“The attempt to maintain an over-valued rupee has had far reaching effects –as similar attempts have had in every other country that has tried to maintain an overvalued currency. The rise in internal prices without a change in the official price of foreign currency has made foreign goods seem cheap relative to domestic goods and so has encouraged attempts to increase imports; it has also made domestic goods seem expensive to foreign purchasers and so has discouraged exports. As a result, India’s recorded exports have risen much less than world trade on the whole, while the demand for imports has steadily expanded…

The fact is that the planners cannot possibly know what they would have to know to ration exchange intelligently. Instead, they resort to the blunt axe of cutting out whole categories of imports; to the dead hand of the past, in allocating a certain percentage of imports in some base years; and to submission to influence, political and economic, which is brought to bear on them. And they have no alternative, since there is no sensible way they can do what they set out to do.

The elimination of the exchange-controls and import and export restrictions is thus a most desirable objective of policy. It must be recognized, however, that it would probably increase the demand for foreign exchange, but the likelihood of an increase means that elimination of controls would have to be accompanied by the introduction of some other means of rationing exchange. It should be emphasized that this increase in the demand for foreign exchange is not a fresh problem that would be created by the elimination of exchange-controls. The problem is there now. That is why controls are deemed necessary. The question is whether there are not less harmful ways of solving it.

Do read the two essays that the good folks at Centre for Civil Society have compiled into a small book.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Speech] Monetary policy and inequality: Speech by Isabel Schnabel, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB.

[Article] “The optimal way forward (for climate transition) is a combination of electricity regulation at state governments, a carbon tax led by the union government, and a private electricity sector organised around the price system.” argue Akshay Jaitly and Ajay Shah.

[Podcast] Over at Puliyabaazi, Pranay and Saurabh discuss the only election manifesto BR Ambedkar ever wrote.

[Article] Pranay and Arjun opine in Hindustan Times that India needs one 20-year semiconductor strategy, not twenty 1-year incentive schemes.

Share this post