India Policy Watch #1: Silver Linings Playbook

Insights on burning policy issues in India

- RSJ

Hello Readers! We are back after a nice, little break.

Things have changed a bit in the past four weeks; haven’t they? Stock markets around the world are down by 10 per cent. Central banks have hiked interest rates by 40-50 bps. Inflation in the US is running at a 40-year high of over eight per cent. Retail inflation in India at 7.79 per cent is beyond the zone of comfort for RBI. The Rupee hit an all-time low last week. Technology stocks are down all over the world and the deal pipeline in the digital startup space has all but dried up. Musk is buying Twitter or maybe he isn’t. NFTs are dead and buried and crypto valuations are in a funk (or in a death spiral as Matt Levine puts it). And no one really knows anything about the Ukraine war. It drags on like a Putin-shaped monster waddling its way through the spring rasputitsa with no hope of getting anywhere.

Such then are the vagaries of the world.

Thankfully, the Indian news channels were debating more important issues during these times. Like loudspeaker bans in religious institutions. Like a videographic survey of a Varanasi mosque by a 52-member team. Or if the Taj Mahal was indeed a Shiva temple called Tejo Mahalaya before Shah Jahan, that undisputed emperor of large tracts of Hindustan in the 17th century, figured he had run out of land to build a mausoleum in memory of his late wife. Or if Sri Lanka was more in the dumps than us in these times. These things matter. So they must be investigated by the intrepid reporters sitting in the studios. We must be forever thankful for the oasis of assurance that Indian news channels offer to us in this volatile and uncertain world.

Anyway, coming back to the point, things have turned for the worse since we last wrote on these pages. Yet, amidst all the talks of a recession or stagflation, I believe there’s some kind of silver lining for India if it plays this situation well.

Sweet Are the Uses Of Inflation

First, let’s look at the inflation and the rising interest rate scenario. India didn’t go down the path of expanding the fisc by doling out cash incentives at the peak of Covid induced distress in the economy. Much of the “20-lakh crores package” that was announced in May 2020 was either repurposing of the existing schemes or putting a monetary value on loans, subsidies or free food that was offered to the people. So, while the RBI cut rates and increased liquidity, the supply of money in the system and the government balance sheet didn’t bloat like those in the US and other western economies. The upside of the US model was that the economy rebounded faster, it began running at almost full employment and people who got Covid relief checks started spending as the economy opened up. The downside is an overheated economy that now needs to be cooled down but that comes with its consequences. The war in Ukraine and the resultant rise in oil and commodity prices have queered the pitch. So, for the first time in a long, long time the Fed has had to raise rates while the markets are falling. In 2022, the global rich have lost over a trillion dollars already as markets have fallen while the poor have had their wage increases outpace inflation. There’s less K-shaped recovery discussions in the US happening today. Anyway, these are new scenarios for an entire generation raised on rising stocks, low inflation and low-interest rates. This will be a hard landing for them.

In the model that India followed, on the other hand, there was real distress in the rural and informal economy because of the absence of a direct cash transfer scheme during the pandemic. As the economy opened up, there were supply chain disruptions that hurt multiple sectors. The rise in oil prices because of the war added to the inflation. But there is an important difference between our inflation and that of the West. It is more a supply-side issue for us. A few rate hikes, some stability in oil and commodity prices and our continued diplomatic balancing act that will help us with cheap oil from Russia should stabilise things. We could be looking at a transitory elevated inflation for a few quarters rather than something more structural. Also, we have a much greater headroom to control inflation by raising rates. The repo is at 4.4 per cent after the out-of-turn increase by RBI last week. It is useful to remember as late as mid-2018, the repo was at 6.5 per cent and that didn’t look like a very high rate at that time. So, the RBI has another 150-200 bps of flex to tame inflation without seriously hurting growth, unlike the West. And that is only if the inflation prints get into the teens. That looks unlikely. So, what’s in store for us? We will continue with the trends we have seen so far: a K-shaped recovery that will hurt the poor more, the formalisation of the economy will mean the published numbers of GST collections or income tax mop-up will be buoyant, the food subsidy and other schemes started during the pandemic will continue for foreseeable future and we might get away managing to keep inflation down without killing growth.

Second, the structural inflation in the western economies will mean they will have to take a couple of long-term calls. The discussion on the first of these calls is already on with an urgency markedly different from what it was six months back. How to reduce the dependence on oil and gas that support authoritarian regimes around the world? This shift away from the middle-east and Russia for energy is now an irreversible trend. Expect a rethink on nuclear energy and acceleration on the adoption of EVs. The other call is who should we back to replace China as the source of cheap goods and services to the west? The low inflation that the west has been used to over the past two decades is in large part on account of China’s integration into global trade. Now China wants to move up the value chain. Worse, it wants to replace the US as the dominant superpower. Continuing to strengthen China economically is no longer an option. China has done its cause no favour by being a bully around its neighbourhood (we know it first hand), being a terrible friend (ask Sri Lanka) and creating an axis with Russia and other authoritarian regimes around the world. There’s no going back to a working relationship with China of the kind that was prevailing before the pandemic. It is unreliable and it won’t turn into an open, democratic society with rising prosperity as was expected. It is difficult to see beyond India in filling that China-shaped void if the west were to search for continued low costs. Vietnam, Bangladesh and others could be alternatives but they lack the scale for the kind of shift that the west wants to make. The inflation pressure means the west doesn’t have time. India has an opportunity here. And I’m more sanguine about this because even if India shoots itself in foot like it is wont to, the way the die is cast it will still get the benefits of this shift. This is a window available for India even if it were to do its best (or worst) in distracting itself with useless, self-defeating issues.

Lastly, there are some unintended consequences of a moderately high single-digit inflation for India. This is a government that likes to be fiscally prudent. It didn’t go down the path of ‘printing money’ during the pandemic because it cared about the debt to GDP ratio and the likely censure and downgrades from the global rating agencies. But it is also a government that likes welfarism. Welfarism + Hindutva + Nationalism is the trident it has used to power its electoral fortunes. A rate of inflation that’s higher than government bond yields will pare down the debt to GDP ratio and allow it to fund more welfare schemes. And that’s not a bad idea too considering there’s evidence that things might not be great in the informal economy. That apart, the inflation in food prices because of supply chain disruptions, increase in MSP and the war in Ukraine is good news for the rural economy. After a long time, the WPI food inflation is trending above CPI which means farmers are getting the upside of higher food prices. I guess no one will grudge them this phase however short-lived it might be.

Well, I’m not often optimistic on these pages. But the way the stars have aligned themselves, India does have an opportunity to revive its economy in a manner that can sustain itself for long. The question is will it work hard and make the most of it? Or, is it happy being lulled into false glories and imaginary victimhood from the past that its news channels peddle every day?

A Framework a Week: Errors of omission and commission — how VLSI relates to subsidies

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

(This article is an updated version of my 2014 essay on nationalinterest.in)

The fundamental idea of any testing is to prevent a faulty product from reaching the end consumer. A well-designed test is one that accurately identifies all types of defects in the product. Very often though, this is not possible as tests may not cover the exact range of defects that might actually exist. In that case, the suite of tests leads to errors of commission or omissions. The interesting question, then is — which of the two errors is acceptable?

An illustration

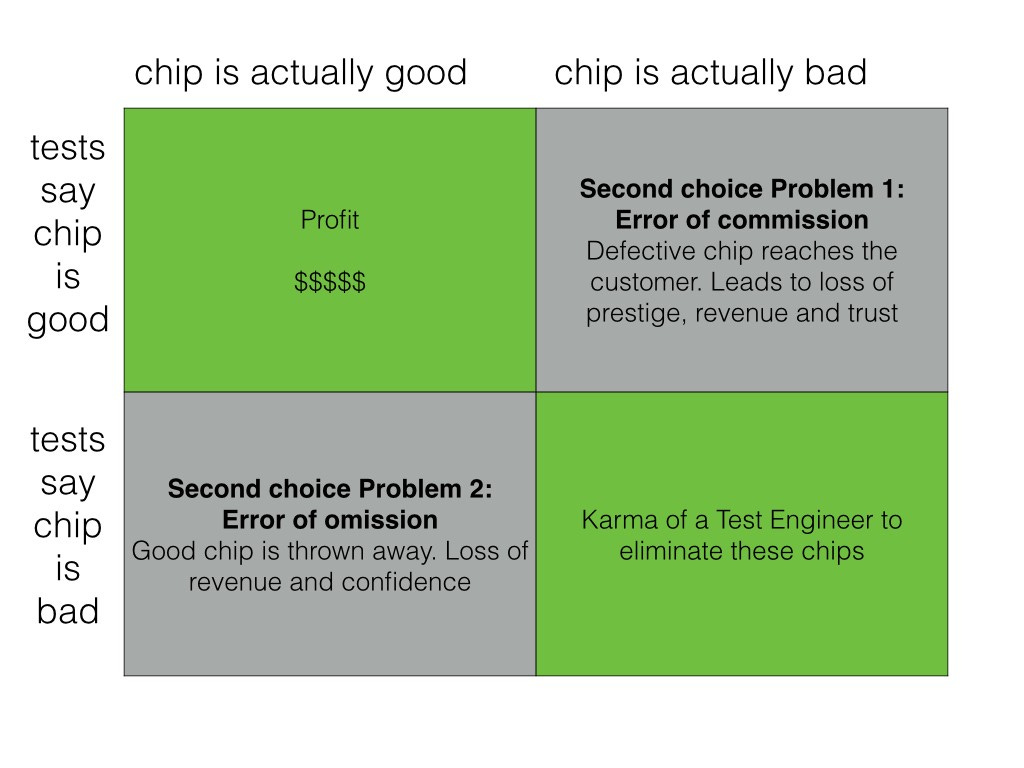

This second problem can be explained using a fairly simple scenario from “Design-for-Testability” theory used in all integrated chip (IC) manufacturing companies. Consider a firm that makes the processor chips going into your laptops. Every single processor chip goes through a set of tests to identify if the chip is good or bad. Four scenarios result from this exercise:

The two scenarios marked in green are the best-case scenarios. In the first of these, all the designed tests are unable to find any fault with the chip. At the same time, the chip itself does not show any defects after reaching the end consumers. When such awesomely functional chips reach your laptops, the chip-making companies make profits.

In the second “green” scenario, the tests indicate that there is a problem with the chip. Further debugging (which involves greater costs) concludes that this chip is actually manufactured erroneously. It is then the raison d’être of the tests to throw away these chips so that they do not reach the customers.

However, when tests are unable to identify any problem with the chip even though it is bad, we end up in the second choice problem 1 scenario or the “error of commission”. This is the scenario you encounter when your laptop crashes within a few days/weeks/years (within the guarantee period) after purchase. Obviously, this makes the consumer lose trust in the product and dents the manufacturing firm’s image.

On the other hand, there is the second choice problem 2, where tests are designed so thoroughly that they start eliminating chips which are actually not dysfunctional. This is the Error of Omission. The cost involved with this error is that it leads to a loss of revenue as many good chips are just thrown away based on faulty tests. It also lowers the confidence of the firm.

The above illustration shows the two errors that are commonly encountered in the chip manufacturing business. Which of them is tolerable is a function of the company’s image in the market, the end application of the product and the costs involved. For example, if the chip is being manufactured for use in mission-critical automobile systems like auto-braking or fuel injection, the preferable error is the error of omission as there’s a life and personal safety at stake. On the other hand, if the end application is a low-end mobile phone, the company might settle for a higher error of commission and avoid the extra costs of rejecting lots of chips.

Application — Subsidies

The above illustration can directly be applied to a subsidy case to explain the effect of identifying beneficiaries incorrectly. Using the framework above, we can visualise a subsidy program as shown in the figure below:

From the framework above, which would be your second choice? The first option would be to start with very few beneficiaries being fully aware that there will be a definite Error of Omission. The next step would be to work on reducing this error rate itself. The problem here will be that there might be some people who, even though needy are not attended to urgently.

Another option would be to start with a large number of beneficiaries being aware of the errors of commission. A subsequent step would be to try and reduce this error rate. The costs involved here are that the free-riders might sideline the really needy. Such schemes will also require huge sums of capital as they will start by serving a huge number of people. This is the path that most government subsidies follow in India. A digital identity project like Aadhaar plays a role right here — it can reduce the errors of commission.

If you were to design a subsidy scheme, which would be your second choice scenario? Thinking about second choices is generally useful in public policy as the first-choice option is often unavailable. The art of policymaking lies in picking a second-best option that makes most people better off.

India Policy Watch #2: Samaaj Ke Dushman

Insights on burning policy issues in India

- RSJ

Here is a quote for you to ponder over:

All these theoretical difficulties are avoided if one abandons the question “Who should rule?” and replaces it by the new and practical problem: how can we best avoid situations in which a bad ruler causes too much harm? When we say that the best solution known to us is a constitution that allows a majority vote to dismiss the government, then we do not say the majority vote will always be right. We do not even say that it will usually be right. We say only that this very imperfect procedure is the best so far invented. Winston Churchill once said, jokingly, that democracy is the worst form of government—with the exception of all other known forms of government.

Sounds relevant to our times?

Over the past month, I have been reading Karl Popper’s “Open Society and Its Enemies”. It is a wonderful book written during WW2 when open and democratic societies were facing their most difficult test yet. The key question Popper is interested in is how do we avoid democracies falling into the trap of turning themselves inwards and giving into a majoritarian system of governance. Seems like as relevant a question as it was during the time of his writing.

While reading the book, I chanced upon a most amazing essay written by Popper himself about his book in The Economist in 1988. Reading it three decades later, it is remarkable how accurate he is in first framing the core question of a democracy right and then looking for solutions that can be tested with scientific rigour.

I have produced excerpts from that essay below:

In “The Open Society and its Enemies” I suggested that an entirely new problem should be recognised as the fundamental problem of a rational political theory. The new problem, as distinct from the old “Who should rule?”, can be formulated as follows: how is the state to be constituted so that bad rulers can be got rid of without bloodshed, without violence?

This, in contrast to the old question, is a thoroughly practical, almost technical, problem. And the modern so-called democracies are all good examples of practical solutions to this problem, even though they were not consciously designed with this problem in mind. For they all adopt what is the simplest solution to the new problem—that is, the principle that the government can be dismissed by a majority vote…

My theory easily avoids the paradoxes and difficulties of the old theory—for instance, such problems as “What has to be done if ever the people vote to establish a dictatorship?” Of course, this is not likely to happen if the vote is free. But it has happened. And what if it does happen? Most constitutions in fact require far more than a majority vote to amend or change constitutional provisions, and thus would demand perhaps a two-thirds or even a three-quarters (“qualified”) majority for a vote against democracy. But this demand shows that they provide for such a change; and at the same time they do not conform to the principle that the (“unqualified”) majority will is the ultimate source of power—that the people, through a majority vote, are entitled to rule.

Popper’s answer is the two-party system. The Congress is busy with its chintan shivir as we speak and I read Popper with bemusement when he wrote on the merits of a two-party system.

The two-party system

In order to make a majority government probable, we need something approaching a two-party system, as in Britain and in the United States. Since the existence of the practice of proportional representation makes such a possibility hard to attain, I suggest that, in the interest of parliamentary responsibility, we should resist the perhaps-tempting idea that democracy demands proportional representation. Instead, we should strive for a two-party system, or at least for an approximation to it, for such a system encourages a continual process of self-criticism by the two parties.

Such a view will, however, provoke frequently voiced objections to the two-party system that merit examination: “A two-party system represses the formation of other parties.” This is correct. But considerable changes are apparent within the two major parties in Britain as well as in the United States. So the repression need not be a denial of flexibility.

The point is that in a two-party system the defeated party is liable to take an electoral defeat seriously. So it may look for an internal reform of its aims, which is an ideological reform. If the party is defeated twice in succession, or even three times, the search for new ideas may become frantic, which obviously is a healthy development. This is likely to happen, even if the loss of votes was not very great.

Under a system with many parties, and with coalitions, this is not likely to happen. Especially when the loss of votes is small, both the party bosses and the electorate are inclined to take the change quietly. They regard it as part of the game—since none of the parties had clear responsibilities. A democracy needs parties that are more sensitive than that and, if possible, constantly on the alert. Only in this way can they be induced to be self-critical. As things stand, an inclination to self-criticism after an electoral defeat is far more pronounced in countries with a two-party system than in those where there are several parties. In practice, then, a two-party system is likely to be more flexible than a multi-party system, contrary to first impressions.

PolicyWTF: The Wheat Ban Photo Op

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Pranay Kotasthane

The Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) has banned wheat exports from India with immediate effect. For an expert’s view on why this ban is a policyWTF, read Ashok Gulati and Sachit Gupta’s take in the Indian Express. The article lists three less-worse options that the government chose to ignore, and opted for this rather extreme step instead. From a broader public policy perspective, there are three points to learn from this PolicyWTF.

One, it reflects the perilously increasing scope of what’s classified as “strategic”. Once an item gets that tag, a fundamental concept behind international trade that “only individuals trade, countries don’t”, gets defenestrated.

Here’s why I think this “strategic” line of thinking is the real reason behind this policyWTF. Until 11th May, the message from the government was that it has procured sufficient stocks of wheat and that there is no plan for an outright ban on exports. The PM in his recent visit to Germany even proclaimed that Indian farmers have “stepped forward to feed the world" even as many countries grapple with wheat shortages. There were reports that the government might consider an export tax on wheat; a ban wasn’t on the cards. A May 14 Business Standard report cited an unnamed senior official thus:

“We have worked on four-five policy measures to curb this unabated flow of wheat from India. A final decision on this is yet to be taken. We are waiting for approval from the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO).”

So it seems that it was the PMO that opted for this extreme step. Why, you ask? The reason perhaps lies in the exceptions to the ban. The government plans to permit wheat exports bilaterally, on the request of specific countries. In one fell swoop, every bag of wheat being exported by an Indian farmer now becomes an economic diplomacy photo-op for the government. While this may seem like a masterstroke for the government, this ‘strategy-fication’ comes at the immense expense of farmers and traders. While they will not be able to cash in on the immediate opportunities, they might also receive smaller if not fewer international orders from international buyers in the future.

The second lesson from this PolicyWTF is for the farmers. While this particular ban will undoubtedly hurt the farmers and traders, its origins lie in the now-normalised intervention of governments in all aspects of agriculture. In that sense, Minimum Support Prices (MSP) and the wheat ban are two sides of the same coin. A government that giveth will also taketh at whim. The push for making MSP a law is likely to invite more such export bans from the government, in the name of consumer interest.

Observe the ease with which the State can take away economic freedoms in this statement by the Commerce Secretary:

"So, what is the purpose of this order. What it is doing is in the name of prohibition - we are directing the wheat trade in a certain direction. We do not want the wheat to go in an irregulated manner to places where it might get just hoarded or where it may not be used to the purpose which we are hoping it would be used for”.

The third policy lesson is the need to lift the bans on genetically edited crops. The ostensible reason for this ban was a decrease in production due to the heatwave in large parts of India. Assuming that climate change will lead to many more instances of crop failures, crops engineered to withstand higher temperatures are an important part of the solution.

In the wake of the ongoing wheat shortage, there are signs that the regulatory environment is changing in a few countries. Australia and New Zealand approved a drought-tolerant Argentinean wheat variety for human consumption last week. Many countries now classify gene edited crops that do not use DNA from a different organism, as non-GMO. Indian regulators hopefully too will move in the same direction.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Post] The Indian ‘sedition’ law was in the news last week. We had a conceptual take on sedition in edition #115 that puts the current events in context.

[Podcast] What’s it like to grow, operate, and sell a manufacturing firm in India? That’s the theme of the latest Puliyabaazi with Hema Hattangady.

[Book] Lithium batteries are all the rage. For understanding the politics and the geopolitics of these batteries, read Lukacz Bednarski’s succinct Lithium: The Global Race for Battery Dominance and the New Energy Revolution. For a short introduction to battery failure accidents in India, here’s a nice primer by Saurabh Chandra on Puliyabaazi.

Share this post