#42 Baithe Baithe Kya Karein?

State Capacity, Right and Wrong of Ages Past, Taxation, Online Trading as the new Antaakshari, and more

This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

India Policy Watch #1: An Unmissable Opportunity to Build State Capacity

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

In Political Order and Political Decay, Francis Fukuyama argues successful societies stand on three pillars – a strong state, rule of law and democratic accountability.

The key is to get the sequence right. A strong state must come first. States that democratise first, without building adequate state capacity, struggle. The government gets overwhelmed by the competing demands from different groups. It either succumbs to majoritarianism or gets consumed by internecine strife. This explains the failures of democracy in many countries that won their independence post WW2.

Does that mean countries should hold off democracy till they build state capacity? That’s difficult to sell to people who have been denied representation and share of power for ages. Also, how does a state become strong? We have countries that owe their state capacity to history. China has a long history of strong dynasties that centralised power to keep the many tribes in its periphery under check. South Korea and Japan built state capacity over years of monarchy or dictatorship before embracing democracy. There’s a strong path dependence to building state capacity. History matters.

So, is history destiny? Fukuyama believes states that got the sequence wrong – democracy first without a strong state – have needed shocks, like wars, to accelerate building of state capacity. The Civil War and the reconstruction that followed helped the US, while the two World Wars built capacities in western European democracies.

War minus shooting

How does India fare on the three pillars? Fukuyama contends India does well on democratic accountability and rule of law but lacks state capacity. This is not about big or small government. It is about a strong state being effective and doing things well regardless of the number of things it does. India has the sequence wrong. It became democratic while its history of fragmented princely states or a rapacious colonial ruling power didn’t offer any legacy of a strong state. There are exceptions to this history which explains pockets of better governance like Kerala, Mysore, Goa and parts of north-east.

Over the years, the state got bigger, not better, searching for that elusive capacity. It made matters worse with the license permit raj of the 60s and 70s setting India back by decades. India went through a period of reforms trying to get the state out of areas that markets could manage better. But this didn’t mean a secular, planned retreat from many areas and diverting capacity to a narrow list of priorities. Instead, while the state weakened in areas it quit, regulators with untrammelled powers replaced it. In other areas, the state continued its overarching and ineffective hold.

The current pandemic, like wars, is the kind of shock that Fukuyama cites for building a strong state. Kelkar and Shah in their book, In Service Of The Republic, also make a similar point:

In the early history of many successful states, the leadership focused primarily on two problems: raising taxes and waging wars. Learning-by-doing took place through the pursuit of these two activities. State capacity in the early days in the UK and in Sweden was learned by building large, complex organizations which raised taxes and waged wars.

The learning-by-doing that took place was not just about the narrow problems of raising taxes and waging wars. The learning-by-doing that took place was about larger ideas about how to organize the state (emphasis ours). The general capability of public policy and public administration was learned in these two areas, which was then transplanted into other areas… (contd)

…. If we live in a country with low state capacity, how does this change our thinking? In the international experience, waging war was an important pathway to developing state capacity. That pathway is not open to India, given the nuclear deterrent.

Well, for India, the war pathway opened up with the pandemic. This is a war-like opportunity to build effective state capacity that’s long-lasting and widely accepted in the society. So, how have we done so far?

Failing to plan, planning to fail

The past three months have exposed the planning deficit of the state. The severity of the lockdown, its duration and the chaos in lifting it when the curve has anything but flattened, place India in a league of its own. While it is easy to dismiss this line of criticism by asking for the counterfactual, there’s growing evidence we will have worse of both lives and livelihoods by the time we are done with this. Some part of this deficit can be attributed to a strong leader who trusts his instincts. But there’s no denying the large part played by India’s poor administrative capacity. This has meant a series of failures - lack of a wider consultation before announcing the lockdown, poor data analysis and response mechanism, patchy coordination between union and states, a bungling bureaucracy that floods us with circulars, clarifications and retractions and the usual distrust of seeking help from the private sector in managing the response.

A state whose constitution leans towards centralisation and a government with the strongest PMO in history should have started with an advantage in planning and coordinating the emergency response. It didn’t.

Incentives, incentives, incentives

The other area that stands exposed is how the incentives of state-run institutions work at cross-purpose with the policy objectives. The RBI and the finance ministry worked in tandem to cut rates, change reserve ratios and infuse liquidity into the banking system. PSU banks that account for 75 per cent of the market didn’t play ball. The excess liquidity remained parked at RBI at overnight repo rates. The fear of 3Cs (CVC, CBI and CAG) has distorted the incentive to take decisions among bankers. The bankers have seen the pendulum swing from ‘phone-banking’ model of giving loans (receive a call, clear the file) to being hounded by 3Cs for even a legitimate decision.

Even after FM made specific assurances about 3Cs and the ministry announced a package with government backstops, the actual disbursements have been meagre. Reports suggest older loans being renewed at newer rates instead of fresh disbursements to businesses affected by COVID-19. MSMEs, small businesses and specific sectors like food, hospitality and travel continue to struggle for liquidity.

Banking isn’t an isolated example. The inability of state-run organisations to scale the manufacturing of test kits, the low level of testing in many states to keep the numbers low and project control, the blame game between the rail ministry and states on running the shramik special trains and the inability to support migrants because, as the FM said, the state has no database; all lead to a simple conclusion. State-run institutions don’t have their incentives aligned to co-operate and solve problems during a crisis. Blaming others or private sector is easier.

Stop, or, I will shoot

While the state has come up short on enabling, it has outdone itself on stopping things. Bans, curfews, fines, price caps, arbitrary rules to regulate inter-state movements have all been part of its arsenal. Early on during the lockdown, we wrote about India being a ‘Republic of No’. Two months later, we have been surprised by our prescience.

The Indian state, like all states, is coercive. Its power of coercion though works best when it denies something; when it says no. The executive capacity isn’t geared to enable the rights of citizens. But it is very effective at curtailing them. A state derives its legitimacy when it recognizes the ‘reasons of belief’ of its citizens and then exercises its monopoly of force over the citizens in a way that doesn’t repudiate those beliefs. In India, this is easy. The one strong belief among its citizens is that of the state as a ruler with unlimited powers. The Republic of No follows from here.

The strong state paradox

Fukuyama pitted his strong state argument against the ‘orthodoxy’ of the Chicago school of neoclassical economics favouring a limited role of the state that dominated American policy for the most part of the last four decades. This crisis, like others in the past, has shown the markets can’t do all the heavy lifting. A strong state can intervene and move mountains at crunch time. But there’s a paradox inherent there. The sine qua non for a state that’s not all-controlling is a strong state that knows how to get there. You need to be strong to not be overbearing.

For Fukuyama, this is a balancing act that smart leaders have achieved. Leaders who get most big decisions right and those who build consensus than polarise. Applying these conditions – strong state, smart leader, non-polarised polity – provides a good framework to understand which countries got their COVID response right. The usual axes of authoritarian-democratic, welfare-market, or woman led-man led don’t explain it. The countries that got the health and the economy response right are those that tick all the three boxes – a strong state, a smart leader and a society in harmony with its differences. US, UK, China (no propaganda can wipe away its failure in containing this), Russia, Brazil and India fall short. South Korea, Germany, Japan, New Zealand and Australia do well.

Leadership matters

In last three months, the Indian state has gotten bigger and more intrusive with quiet acquiescence from people. But not more effective. This is a pity. India doesn’t tick the boxes on a strong state and a society in harmony. On smart leader, let’s just say, the jury is still out. The pandemic shock is an opportunity for PM Modi to build an effective and less controlling state capacity, free up markets and unite the country to face a common adversary. A smart leader with an eye on his place in posterity would not let this go. The other goals of aatmanirbhar Bharat or being a vishwaguru would follow.

The clock is ticking for him.

PolicyWTFs: Of Complex Laws & Impossible Taxes

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Pranay & Raghu

Gujarat vs Kerala model: redux

Of course, we will cover the parota story. The Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Custom (CBIC) clarified on Friday that the Authority of Advanced Ruling (AAR) has decided frozen and preserved parota is not plain roti but a distinct product.

The ruling is a case study on clear communication. The word ‘impugned’ makes an appearance that settles all my doubts about the intellectual rigour behind this decision:

Further, the products khakhra, plain chapatti and roti are completely cooked preparations, do not require any processing for human consumption and hence are ready to eat food preparations, whereas the impugned product (whole wheat Parotas and Malabar Parotas) are not only different from the said khakhras, plain chapatti or roti but also are not like products in common parlance as well as in the respect of essential nature of the product.

India has low state capacity. It must use it for the maximum impact in very specific areas. One way to conserve state capacity is to make simple laws whose compliance is easy on state capacity. India does the opposite.

Also, khakhra at 5 per cent and Malabar parotta at 18 per cent!

Another wrong-wing conspiracy to prop the Gujarat model over the Kerala model.

Further, this tendency to come up with multiple rates based on narrow classification criteria suggests that Indian governments still believe that a tax policy can have many, many purposes — equalising incomes being one of them. We had written why this is a PolicyWTF in Edition #10. In short:

Redistribution should be one of the goals of the expenditure side of the budget. Raising revenues shouldn’t be tasked with this goal at all. Broadening the base, lowering the tax rates for all individuals and companies, and getting rid of tax exemptions is more progressive than a highly progressive taxation.

Dr M Govinda Rao had this valuable insight on the matter:

Wildlife Misconservation

You would have come across the tragic news of the killing of an elephant in Kerala because it ate a firecracker-stuffed pineapple. Apparently, such crackers are meant to kill wild boars entering farms. But why would someone use such a crude method instead, you ask? This report by Nidheesh MK has the answer:

“As per the existing law, the killing of wild boar, whose numbers have surged ahead and largely account for a big chunk of the conflict-related cases, should only take place with a single gunshot, whereas getting a gun itself is a laborious process," said Shaji.

“The presence of a forest official and a conservation activist, which Kerala does not have enough, is a must for such killings. The dead boar should then be subjected to postmortem and then set to fire and buried in a deep pit. In return for all of these troubles, the farmer’s incentive is only a ₹500 reward," he said.

“Following laws are far more expensive, while making a crude bomb is cheap and accessible, even if that puts him on the wrong side of the law. But in the forests, who is going to know? As a result, the first ‘legal’ killing of a wild boar based on the order, issued in 2011, happened only last week," said Shaji.

Surprise, surprise, it’s another impossible law to comply with. Such laws drive activities “underground” and lead to the worst possible outcomes, like in this case.

A Framework a Week: The Right & Wrong of Ages Past

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

This is not a framework for public policy per se. Nevertheless, something that comes often in public debates is the issue of passing moral judgment on someone from the past.

I bring this up because of the recent calls to remove Gandhi’s statue in Leicester on the grounds that he was a ‘racist’. As strange and abhorrent this thought of “cancelling” someone like Gandhi is, let’s turn our attention to this central question: should we judge people from the past for their supposed ‘immorality’?

I had written an essay on Pragati proposing a framework to answer this question. I’m reproducing parts of that essay here.

Broadly, there are three answers to this question. The first one is a relaxed condition that forms the basis of a philosophical position known as moral relativism. It states that values, mores, and institutions evolve over time and across geographies. The values that we hold dear today were often unimportant for societies of the past. Hence, judging people from the past based on modern values is unfair—morals are relative.

Let me explain with an example. One of the greatest speeches in the history of post-independent India is Grammar of Anarchy by the polymath BR Ambedkar. (Read it now if you haven’t.) A section of this speech reads as follows:

As has been well said by the Irish Patriot Daniel O’Connel, no man can be grateful at the cost of his honour, no woman can be grateful at the cost of her chastity and no nation can be grateful at the cost of its liberty. This caution is far more necessary in the case of India than in the case of any other country.

Seen from today’s worldview, it is clear how even this monumental speech has its dark spots. Pinning the importance of chastity on women alone will be considered problematic by most liberal societies today. This section of the speech can then be used to construct a narrative of how even Ambedkar was patriarchal in his thought. A moral relativist would disagree though. She would argue that this allegation is unfair to Ambedkar because the association of chastity with women was a prevalent thought during those times.

A diagonally opposite viewpoint to moral relativism is an extremely strict condition called moral absolutism. This position says that there are universal standards of right and wrong to which all people should be held regardless of their circumstances. It doesn’t matter where or when they are. This position would be extremely critical of Ambedkar for his disregard of a universally acceptable standard that men and women should be treated equally.

The third position lies somewhere in the middle of model relativism and moral absolutism. Philosopher Miranda Fricker explains this position in a brilliant BBC Magazine article as follows:

The proper standards by which to judge people are the best standards that were available to them at the time.

Let’s term this philosophical position as moral standardism. My view is that this particular approach can help us navigate the complex historical debates in India far better. When applied to the current debate, a moral standardist would ask: what were the best standards of conduct on the issue of race during Gandhi’s time? Are there examples of his contemporaries adopting standards that were much better than he did?

From this position, listing the good deeds of Gandhi to counter his supposed ‘immorality’ becomes irrelevant because it can easily be argued that all historical characters are complex and layered, not monochromatic as they are commonly made out to be. The focus instead is on: could he have known—and done—better based on the standards of the era he operated in?

Do write to us and let us know which of these three perspectives make sense to you. Or maybe there’s a fourth.

India Policy Watch #2: Our Policies, Their Policies

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

I have wondered here a few times about the stock market performance in the pandemic times. Who wouldn’t? The Nifty 50 was at 7610 on March 23 when India had a total of 497 COVID cases. Since then we have had some pain in the economy. In April, industrial output contracted by 55 per cent, trade fell by 60 per cent, 120 million people lost jobs and zero cars were sold (y-o-y figures). May data is trickling in but don’t expect a miracle. Nifty closed this Friday at 9972. A growth of 31 per cent over the lockdown. Nasdaq in the same period is up 39 per cent.

I can make a half-decent case for this divergence between the real economy and the markets in the US.

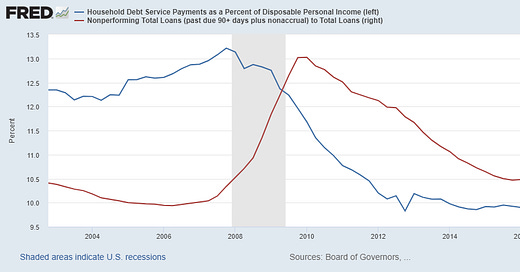

The US economy and the banking system came into this crisis stronger than how they were placed during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2009 (Q4 2007 vs Q4 2019)

Household debt service ratio was 13. 2 compared to 9.7. The average household has a lower loan burden this time

Non-performing loans to total loan ratio was 1.64 compared to 0.85; Return on average equity for all US Banks was 7.4 compared to 11.4. The financial system is in a better position to help the main street now

The US Fed and Treasury are in a tango that the markets can’t take their eyes off

The Fed balance sheet has ballooned from $4.2 trillion to $7.2 in three months: Fed has thrown the kitchen sink at the problem

The total money supply, Money Zero Maturity (MZM) stock, is at an all-time high of $17.4 trillion with the highest ever increase in any quarter of $548 billion in Q1 2020. The maximum increase during GFC in any quarter was about $426 billion: The US government is borrowing this money ($3 trillion already) and the Fed is directly providing credit to the private sector

Despite the record unemployment numbers, the Fed and Treasury tango has meant there’s more money in the hands of the average American through Payroll Protection Programme (PPP) and unemployment benefits

Real disposable income is up 13.7 per cent in April 2020 from a year ago. Personal savings rate is at 33 per cent in April 2020 compared to 6-8 per cent range for the last decade: US households have more money than usual, and they aren’t spending it because of the lockdown. There’s a possibility of demand recovering sharply based on this data.

All of the above could amount to nothing if the real economy doesn’t pick up and the Fed and Treasury stop their unlimited stimulus. The US fiscal deficit is projected to be 18 per cent and there’s a limit to profligacy. But in the short-term, this is sustaining the US markets. The Fed is prepared to take on the risks of inflation and dollar devaluation which will follow soon to keep up the appearances.

How India is different

Now, contrast this with India. The aatmanirbhar package has fiscal stimulus adding to less than 1 per cent of GDP. The liquidity stimulus isn’t direct with government backstops except for the Rs. 3 lakh crores MSME package. The government has increased borrowing but that seems to plug the revenue gap more than signalling an intention to spend. Do the three factors above hold in India?

The Indian economy and banking sector were at their weakest in over a decade coming into this crisis

For the quarter ending March 2020, the GDP growth was at 3.1 per cent and private consumption growth at constant prices was at 2.7 per cent (the lowest in five years)

Gross NPA (%) in October 2019 was at 9.8 per cent compared to 2.3 per cent in October 2007; Return on Equity was a negative RoE of 1.8 per cent in April 2019 compared to 17 per cent in October 2007. The banks will struggle to support the stimulus efforts in this crisis

RBI and MoF are working in tandem but the is the impact is yet to be seen

M3 money supply (the total money stock) grew (y-o-y) by 10.2 per cent in April and 11.6 per cent in May which is a minor change from the usual 9-10 per cent growth range

Private sector credit growth has slowed down to below 7 per cent in April 2020 from the 11-13 per cent range they have been in over the past five years

Since the economic package was focused on the supply side, the savings or household incomes will not see a rise anytime soon

The gross savings rate fell to a 15 year low in 2019 to 30.1 per cent. It was 36 per cent in 2007-08 when the GFC hit India

Private sector gross salary growth was also at a low of 7 per cent in 2019 compared to over 20 per cent in 2007

(source data: RBI)

India came into this crisis with a slowing economy and a hobbling banking sector. Its policy wriggle room was small, and the package announced doesn’t cut it in stimulating demand. Yet, its markets seem to behave like the Indian economy is part of the US stimulus package.

Either they know our policymakers will get to the same place over time or they should prepare for a hard landing soon.

Online trading is the new antaakshari

Of course, this could all be because of what Matt Levine calls the boredom market hypothesis (BMH). In his words:

“People got bored in their coronavirus-related lockdowns, and they couldn’t bet on sports because sports were cancelled, so they turned to betting on stocks as a form of entertainment, not investment or financial analysis. The stock market is a casino that happens to still be open.”

Robinhood, the zero-commission trading app, raised $280 million last month on the back of adding three million funded account since January. The so-called ‘Robinhood traders’ are having fun at the casino. As the Reuters reported this week:

Increased savings, stimulus checks from the government, and ultra-low interest rates due to the coronavirus pandemic have led to a flood of money into the markets from punters, leading to chaotic trades via mobile phone apps.

A little-known Chinese online real estate company’s American depository shares (ADSs) jumped as much as 1,250% on Tuesday before closing 400% higher. The reason cited widely on social media was a part of its name, FANGDD Network.

“In my 20 years of experience I’ve never seen retail traders push stocks around like they’re doing right now,” said Dennis Dick, a trader with Bright Trading LLC. “When the retail rush comes into something, it can really move.”

At least three London-based traders said the surge was down to “Robinhood” traders - Robinhood is a popular stock trading app that greets visitors to its website with the motto “It’s Time to Do Money.”

India seems to be no different. Zerodha, the Indian zero commission trading platform, has added a record 3 lakh customers in the last two months and over 12 lakh new investors opened demat accounts with CDSL in March and April. To put that in context, the previous 11 months had seen 40 lakh new investors with CDSL.

Online trading is the new antakshari for the bored middle class.

Also, I guess it is time to revisit that apocryphal story about J.P. Morgan and the shoeshine boy.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] David Beckworth speaks to Peter Stella about central bank balance sheets, off-balance sheet transactions and crisis financing

[Podcast] Europe in the time of Coronavirus: LSE public event series

[Article] Franklin Foer in The Atlantic on the eagerness of Big Tech to help governments in coronavirus response

[Podcast] In case you are interested in knowing how geopolitics over semiconductors between the US, China, and others is playing out, we have an episode for you

That’s all for this weekend. Read and share.

Excellent newsletter this week!