#175 A Subtle Art Called Taxation

A review of the 5-year old GST, Basic Structure Doctrine and Constitutional Immutability, and Punjab's Struggling Economy

India Policy Watch #1: The GST Completes a Full Election Term

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

On July 1, 2017, the Constitution's One Hundred and First Amendment Act introduced a national Goods and Services Tax (GST) in India. GST was a long-awaited reform that aimed to simplify the complicated indirect tax regime. It took over fifteen years, numerous councils and empowered committees and political wrangling before it was unanimously passed in both houses. As a policy change, things don’t get bigger. It was positioned as a ‘Good’ and ‘Simple’ tax that will make filing easier, improve compliance and improve ease of doing business. Its fifth anniversary is a good occasion to reflect on how it has fared on its objectives.

First, despite some initial hiccups, the entire GST machinery works well. It isn’t the smoothest of experiences for the tax filers and it still has elements that keep CAs employed but no one will deny things have gotten better every passing year. I may be accused here of having a very low bar of success. But anyone who has rolled out a new system across India in their organisation with their limited scope will appreciate the complexity of implementing this. Also, remember there have been multiple instances of such implementation failing and being rolled back in other countries with far lower challenges than India. We now have a foundation that is fairly robust and there’s no turning back on this. This is more than a modest success for what is fundamentally a good policy reform.

Have the tax collections gone up? The nature of a VAT and input tax credit regime is such that there’s an incentive built in for filing GST returns. That along with a focused drive on compliance has meant we have widened the tax base. The expected formalisation of the economy that GST was supposed to push has happened. This is good news. The newspapers report with a degree of triumphalism the highest ever GST collections almost every other month when the data comes in. So, the general sense is we have indirect tax buoyancy because GST is now working as was expected. But if you look deeper, the numbers are misleading. We were averaging monthly indirect tax collections at about Rs. 85,000 crores in 2016-17. We expect it to be at about Rs. 130,000 crores in 2022-23. That’s about a 50 per cent increase. The nominal GDP over these 6 years must have gone up by about 60 per cent notwithstanding the pandemic in between. You can play around with definitions to show that the tax-to-GDP ratio has actually gotten better as some have done. But at a macro level, the most generous conclusion would be it has remained in the same range as before or dipped slightly. The benefits of efficiency or a wider base haven’t materialised.

It will be useful to go deeper into why this has happened. But acknowledging something isn’t working isn’t a feature of this government so I’m not holding my breath on this. My sense is there are a couple of things at play here. The legendary enterprise of businesses to find a way around a tax regime is possibly at play. The on-ground experience of a lot of people in India will vouch for this. The usual kachcha receipt and cash payment models are offered by businesses to customers to avoid the ‘faaltu ka GST’.

The other explanation could be simpler. Maybe the small and medium businesses aren’t doing as well. Greater formalisation has created an advantage for larger, well-capitalised formats in every sector. The informal economy has lost out in the process. And these larger players are then able to utilise all the benefits of the GST regime. So, on an overall basis, the tax collections have remained range-bound.

What about the ease of doing business? A formal GST structure with a single tax regime for the entire country has meant life has become simpler, especially for those who have pan-India operations. The GST system glitches and the difficult user experience in uploading the returns have also reduced quite substantially. This will only get better as systems stabilise and the feedback from users is heard and acted on. However, it is still a complex regime and the flaw is in its design itself.

We have written about these flaws in the past. The number of slabs should have been two or at best 3. We now have a complex array of slabs with definitions of goods that are arbitrary and differ by state. There are the usual parotta and chocolate barfi incidents that come up that make a mockery of the so-called simple tax. There are instances of inverted tax structure where the intermediates are taxed at a higher rate than the finished product. The cess rates as they stand now are way more complex than needed. The problem is that the design tried to optimise for so many different objectives that it has failed to meet its primary goal of a simple tax structure.

Then there is the question of fiscal autonomy of the states and centralisation of powers with the union government. The compensation that was guaranteed to the states for five years to get them to agree to the grand bargain of GST has played out a bit differently than expected. The 14 per cent annual growth in tax revenues forecast was itself too optimistic. The hope that revenue buoyancy will take care of the compensation shortfall in five years was not rooted in any past experience. And then we had the pandemic.

So, we now have the scenario where the compensation cess is likely to be extended till 2026. This is messy and has a built-in moral hazard. The states have very little incentive to protest against arbitrary changes in GST rates of goods because they have, at least on paper, a compensation guarantee. We have made the point earlier here on how this meant the union government could push through some populist rate cuts in the run-up to the 2019 Lok Sabha elections without any protests from the states. This will continue in future going against the goal of a stable and simple tax structure. Also, on fiscal autonomy, the states now have a limited say in their own tax revenues. They voluntarily gave away some of their sovereignty as part of the GST bargain. Now their complaints are piling on. The states rich in natural resources and minerals have got the short end of the stick because these have the lowest GST rates. The producing states complain of revenue losses more than the consuming states with some justification.

The union government has continued on the path of centralising power with arbitrary changes in tariffs and compensation. The structure of the council favours it as well. Any decision that has to be voted on in the GST council requires a three-fourth majority. The union government has a third of the votes in the council. This is a veto that can make things difficult for the ideal of cooperative federalism that GST was supposed to enable. The way things stand today, the electoral dominance of one party has meant this issue isn’t as fraught as it could be. But this might change in future and we need to be aware of that possibility. The current design isn’t conducive to building trust between the union and the states. This could get worse in future.

As things stand today, the implementation of GST seems like a lost opportunity. We have made it more complex than needed and it has been caught up in trying to solve things that a tax regime shouldn’t. What we have now is a stable indirect tax architecture, one that’s widely accepted. We must build on it. This requires sagacity, willingness to appreciate the flaws and going back to the objectives of simplicity and ease. Else, we will have another policy case study with good intentions but patchy implementation.

P.S.: Some of our past editions on this subject:

India Policy Watch #2: Did B.R. Ambedkar & J.K. Rowling Exchange Notes in a Parallel Universe?

Insights on burning policy issues in India

- Guest Post by Bibhudutta Pani

“A butterfly can flutter its wings over a flower in China and cause a hurricane in the Caribbean”

.. said Robert Redford’s character famously in the movie Havana. When I read Pranay’s Addendum in last week’s newsletter it set off, for me, a series of happenings. First, it pushed me down the memory lane to the college classroom where I had first studied Constitution and had wondered about some of the things that Pranay discussed; I fired off my appreciation to him on Twitter, thought about it a little more and emailed him a small note which led to more back and forth and then that’s how I got here. Well, nowhere as dramatic or panning-the-globe phenomenon as Redford was alluding to, but that is my own little butterfly-effect journey into this newsletter.

Pranay discussed how the US and India have picked opposite ends in resolving the Constitutional Immutability Dilemma. The US makes it too difficult to amend its Constitution while it is easy (relatively speaking) to amend the Indian Constitution. While it indeed is correct that it is easier to amend the Indian Constitution, a fascinating element therein is the Basic Structure Doctrine – it essentially sets out what is the holy cow in the Constitution and prevents the legislature from meddling with it. The preamble, rule of law, federalism, and secularism are some of what comprise the basic structure of the Indian Constitution and the doctrine acts as a security cover to protect these core, essential tenets from all forces, including (and interestingly) the Parliament.

It is the “this far and no more” kind of Lakshmanrekha for the Parliament that the Kesavananda Bharati S & Ors. v. State of Kerala & Anr ruling marked out, nearly half a century ago back in 1973. Of course, a larger bench of the Supreme court (Kesavananda Bharati was a 13-judge bench – the largest ever SC bench till now) could overrule this doctrine (and I am inclined to believe it is a real possibility in the near term) but till then, we are at a place where while the how of Constitutional amendment is relatively easy, the how much is not very.

Now turning to my memory of being a college kid. Constitution (or Consti as we called it) was kind of first love in college, its tug strong enough to overpower the lure of other cooler subjects such as criminal law or corporate law. Admittedly though, in the two decades since then, I have not practised the subject or had much to do with it to earn a living. Looking back, it does make a lot of sense – I did very little about my so-called first love except obsess over it inside my head – exactly like a teenager in a one-sided love affair.

Pranay’s piece though reminded me strongly of something that I did do back then. While I had (and have) a poor degree of focus on dates and sequences, armed with my love for Consti, I overcame it and pointed out in the classroom (to Prof. SP Sathe, a luminary himself), the strange occurrence of the 44th Amendment (1978) not being stuck down by the courts even though it deleted a fundamental right i.e. right to property under Article 19(1)(f) & 31.

Timely reminder – fundamental rights are (thankfully!) part of the basic structure of the Constitution and the ruling was passed after the basic structure doctrine came about. Prof. Sathe was a kind man and not a miser when it comes to accolades so he praised me for making a sharp observation and went on to clarify that it (i.e., 44th amendment) was never challenged on grounds of constitutionality and if it were maybe, it would have been struck down as being violative of the basic structure doctrine. He explained to me that society’s mood had changed by then (i.e the 70s as opposed to the 50s) which worked in favour of the 44th Amendment.

I learned, later, about lots of other factors that set the stage – to name a few, the insertion of Article 31A, 31B and the Ninth Schedule by the 1st Amendment which reduced the scope of the fundamental right to property, the land ceiling measures, the lived experience of the society with the concentration of wealth perpetrated by zamindari systems, Justice Khanna’s note in the Kesavnanada ruling, and the successive governmental attempts to nationalise private property and the (partial) backlash from the courts to it, all of which had moulded the polity’s landscape such that the 44th Amendment did not feel like falling-off-the-cliff but only a pronounced speed bump.

The dilemma of choosing for the Constitution to be an inflexible prophecy or an iterated periodical is a real one. But as I reflect upon my decades-old interaction with Prof. Sathe, it feels as though it has, at least in India’s experience, been answered in favour of the former. Even though the Indian Constitution is an inflexible document w.r.t. its basic structure which includes fundamental rights, the Parliament could successfully implement the 44th Amendment as the social and political landscapes were geared toward it. In that process, the Parliament did chip away a few fundamental rights of the people, but the populace did not consider it egregious enough to contest.

So, maybe it isn’t that bad to set out the Constitution as an inflexible prophecy - as the Harry Potter stories remind us, the prophecy in itself may not guarantee an outcome for a great deal rests on the choice of the actors who are subject to it. And there lies an uncanny similarity between what J.K. Rowling expresses and what B.R. Ambedkar opines. In Ambedkar’s words:

“However good a Constitution may be, if those who are implementing it are not good, it will prove to be bad. However bad a Constitution may be, if those implementing it are good, it will prove to be good.”

(Bibhu is a corporate lawyer and writes on matters of law, technology and public policy. He’s an alum of Takshashila’s GCPP programme. Follow him on Twitter @bibhudutta)

Course Advertisement: Admissions for the Sept 2022 cohort of Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy programme are now open! Apply by 23rd July for a 10% early bird scholarship. Visit this link to apply.

India Policy Watch #3: A Fairytale Gone Wrong

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

Earlier this week, a newly formed government brought out a rare White Paper that pulled no punches. Itan thus:

“X is in an economic morass and debt trap. The previous Governments, instead of applying necessary correctives, continued to slip into fiscal profligacy, as evident from the unchecked increase in unproductive revenue expenditure, freebies and unmerited subsidies, virtual collapse in the capital and social sector investments vital for future growth, and non-realization of its potential of tax and non-tax revenues.”

X is not Sri Lanka though there are many similarities between the two. These lines are from a White Paper on State Finances released by the Government of Punjab.

I would have normally dismissed the lines in the white paper as hyperbole, quite common in political one-upmanship contests. In my mind, Punjab and Haryana were two of the richest large states in India. How bad could Punjab’s financial situation today be really?

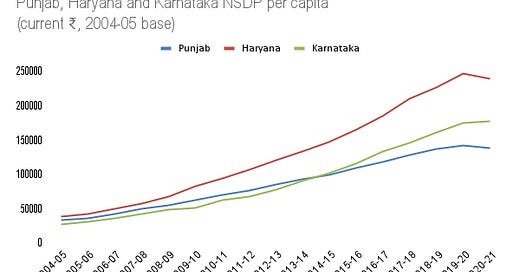

A lot, it turns out. I was jolted out of my assumptions when Sidin Vadukut pointed out that Punjab actually ranks nineteenth in terms of incomes measured as NSDP per capita. Nineteenth, just imagine! Even as neighbouring Haryana continues to occupy the number one spot. All my Bayesian priors about Punjab—rich farmers, luxury cars, remittance-driven investments, etc.—disappeared in that one moment.

The chart below shows Punjab’s economic decline. See the divergence between Haryana and Punjab on one hand, and also how another distant state Karnataka outpaces Punjab.

To those who understand Punjab better, this would not come as a surprise. But still, the economic decline of the state is staggering. Many states in India have always been laggards, while most others fare nowhere near their potential. But there’s no other big state where economic development has fallen this steeply.

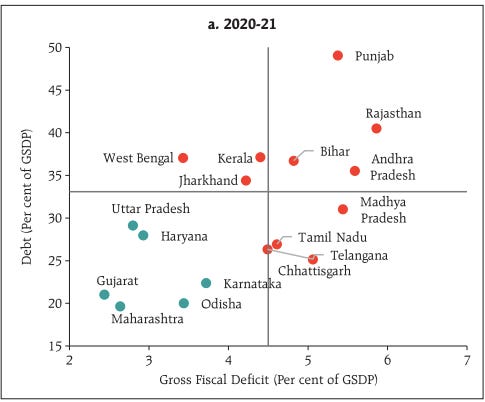

Unsurprisingly, low economic output has damaged government finances severely. Low incomes have meant low tax collections, increasing the dependence on borrowings and union government transfers. Public debt is nearly 48 per cent of the GSDP, the highest among all states by far. Of every 10 rupees the state earns, 2 rupees get spent just on paying the interest on previous debt. The state is now in a classic debt trap—borrowing more to pay older debts.

Despite this troublesome situation, the state’s fiscal profligacy continues. Economists refer to this ability of governments to spend way beyond their means as a soft-budget constraint. Eleven per cent of the state’s total expenditure is on power subsidies alone. The state ranks the lowest among all major states in capital expenditure, meaning that most of the available money (nearly 90%) is being spent on revenue expenditures alone. The Punjab government’s pay scales are higher than the Union government’s.

You get the picture. But what explains it?

Experts point to several factors. A deadly decade of violence (the 1980s), corruption by successive governments, and the quick decline of Punjab’s once best-in-class industries such as cycles, hosiery, and sports goods.

However, I submit that the elephant in the room is State-financed agriculture. In the 1960s, the Green Revolution changed India’s fortunes. Through a focus on high-yielding varieties of seeds, irrigation facilities, fertilizers, and mechanization, the Green Revolution significantly improved the productivity of Indian agriculture and helped India overcome food insecurity to a large extent. Where the government went astray was in deploying a highly interventionist tool like the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for grains.

With no sunset clauses baked into the design and the political economy pushing the “M” in MSP way beyond the Minimum, perverse incentives have compounded over time. The assured support prices have disincentivises not just crop rotation, but also obviated the need for agricultural value addition. Why invest in agri-processing when you are assured of a stable income from growing grains?

Even as Punjab’s industries were being wooed by states such as Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, the complacency of government-financed agriculture disincentivised corrective measures. In fact, electricity tariffs for industries in Punjab started rising in order to cross-subsidise the free power being given for growing grains.

Punjab’s economic trajectory is a stark reminder of the need to avoid changing incentives of millions of producers and consumers by setting prices. Such policies have economy-wide ill-effects lasting several generations.

Meanwhile, the new Punjab government’s task is cut out. Its budget says it is banking on two sources for improving tax collections. One, it plans to introduce more competition in the alcohol supply chain in order to increase total excise collections. And two, it plans to reduce GST evasion through better enforcement. Will the tipplers rescue the economy? I hope so. Don’t let it become an addiction though.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Book] M Rajshekhar’s Despite the State: Why India Lets Its People Down and How They Cope discusses the political causes of Punjab’s poor economic performance in some detail. There’s also this All Things Policy episode on the book by our Takshashila colleagues, Suman and Sarthak.

[Paper] Read India’s foremost public finance expert’s evaluation of the GST’s progress, performance, and prospects.

[Paper] An excellent overview of State Finances by Atri Mukherjee, Samir Ranjan Behera, Somnath Sharma, Bichitrananda Seth, Rahul Agarwal, Rachit Solanki and Aayushi Khandelwal at RBI.

Hi, Pranay 🙂 Using the framework you discussed in the 168th edition of the newsletter, I have made an attempt to understand the constitutional immutability dilemma.

The question of the mutability of a constitution could be an answer to the question “what is the error threshold for amendments?”

Thus, the mutability of a constitution is constrained by the fear of errors — the error of commission and the error of omission.

By constraining the process of amendment, the US constitution commits the error of omission. The Indian constitution leans towards the error of commission.

Here, the error of commission would be adding such stuff to the constitution which wasn’t initially present in the constitution.

The error of omission would be abstaining from adding stuff to the constitution unless it’s strictly allowed by the constitution (!)

When the error threshold for amendments is set high (error of commission), concentration of power and centralised decision-making could quickly erode the nature of the constitution.

Hi Pranay! I love your Substack; it's really cool! :)

I wonder what you think about my piece about economics: https://join.substack.com/p/experimentation.