#54 Missing the Ocean for the Water Purifier

RO water purifier ban, Digital Payments, China's Strategic Culture Myths, and What's Wrong with all Large WhatsApp Groups

This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PolicyWTFs: The Critique Of Pure Ban

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

India loves a ban. Barely a week passes without the state banning something. This is the reason we advocate for ‘ban gan man’ as a more appropriate national anthem. This will take time though. That’s fine. We appreciate public policy advocacy is a marathon.

A Short Story About A Ban

This is what we banned last week — RO purifiers that demineralise water. As long-time connoisseurs of the language in government notifications, we reproduce excerpts below from the 12-page document from the Ministry of Environment & Forest (MoEF) including Schedule 1 (section C, subsection 2).

The prose is incandescent. And I also learnt what flocculation is. No, it is not what it sounds like:

“Installation or use of MWPS shall be prohibited, at the Point of Use or at the Point of Entry for purification of supplied water which is subjected to conventional flocculation, filtration and disinfection process or is from any sources which are in compliance with acceptable limit for drinking water prescribed by Bureau of Indian Standard 10500:2012”

“BIS shall develop system and procedure to monitor, assess, certify the type and process integrity of the MWPS for compliance of provision of Schedule – I in consultation with CPCB. The validity of the certificate shall be as prescribed in the guidelines prepared by BIS. The certificate shall have mention of date of certification, its validity, treatment technology used, recovery efficiency, and other terms and conditions as specified by BIS. BIS shall develop such system and procedure within a period of six months from the date of publication of this notification in official gazette.”

The draft notification is available here. It has 25 items of definition and a list of 59 responsibilities spread across 11 different players (Port Authority also features among them). Here’s our understanding of the rationale for the ban:

RO purifiers reduce total dissolved solids (TDS) in water. This process leads to water wastage. Some estimates suggest for every 100 litres of water purified, about 80 litres of water is wasted.

In locations where the TDS in piped water is already below 500 milligrams per litre (mg/litre), RO water purifiers might ‘demineralise’ the water. This isn’t good. Some minerals in water are important for the human body. Taking them out leads to mineral deficiency with long-term health implications.

So, the ban on RO water purifiers in locations where TDS is below 500 mg/litre. The notification has the usual quota of coercion applied to every stakeholder in the ecosystem – domestic and industrial users, manufacturers, importers and water supply agencies. The National Green Tribunal (NGT) has given the government until the end of 2020 to implement the ban. In a previous hearing, NGT had sent out a tough message to the Ministry of Environment & Forest (MoEF) to implement the ban. It had warned:

“…failure of the concerned officers to comply with directions of the tribunal can lead to punishment under Section 26 of NGT Act, 2010 also by the way of imprisonment, and that December 31 is the deadline for MoEF to comply else from from January 1, concerned officer in charge will not be entitled to draw salary and further coercive measures may be considered.”

There. You can draw some solace. The ministry is getting coerced too.

A Beautiful Ban

The 59 responsibilities outlined in the notification include a bewildering array of inspections, permissions, reports, licenses, standards, monitoring mechanisms and deadlines. To wit, this will need enormous state capacity across agencies to implement.

Like we said earlier, we have a ban in India almost every week. But once in a while, there comes a ban so perfect for explaining what ails policymaking in India that we light three diyas (always in triplicate) at the altar of our public policy kul-devata to express our gratitude. This is that kind of a ban. On the surface it appears like the right thing to do. Anyone who has an RO purifier at home (and who hasn’t in India?) is aware of the water that’s wasted. The intention of the ban seems good.

But we never tire of emphasising, intention counts for nothing in public policy. We will see why in this case.

Voting With Their Feet

Yesterday, I finished Shankkar Aiyar’s excellent new book, The Gated Republic. It has a self-explanatory subtitle – India’s Public Policy Failures And Private Solutions. It is a well-researched, wonderful addition to what I call the ‘Indian republic/state as an adjective’ genre of book or papers (refer to the comprehensive list at the end of this post).

The book begins with making a case for the role of the state in providing for education, health, security, water and electricity. Aiyar quotes Adam Smith from The Wealth of Nations:

“… the sovereign or the government has three duties of ‘great importance’ to attend to. First, the duty of protecting the society from violence and invasion of other independent societies; secondly, the duty of protecting, as far as possible, every member of the society from the injustice or oppression of every other member of it, or the duty of establishing an exact administration of justice; and, thirdly, the duty of erecting and maintaining certain public works and certain public institutions which it can never be for the interest of any individual, or small number of individuals, to erect and maintain; because the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals, though it may frequently do much more than repay it to a great society.”

Aiyar has two central arguments in the book. First, the Indian state has ‘flailed or failed’ in the ‘third duty’ outlined by Adam Smith above. The history of independent India is dotted with public policy failures in delivering basic governance. Second, the citizens of India have normalised these failures and the moment they can afford it, they check out from the state. They find private solutions for education, water, electricity and security while paying their taxes to a state that should be providing these. Aiyar calls it a ‘ceaseless secession”:

“The many failures of public policy are propelling a ceaseless secession.”

“… The voice of the average Indian is not heard and the wait has been too long. And so Indians are desperately seceding, as soon as their income allows, from dependence on government for the most basic of services – water, health, education, security, power – and are investing in the pay-and-plug economy.”

The Problem Of Water

Aiyar starts his book looking at the promise of clean, drinking water to every Indian. He is unrelenting in his analysis of many policy failures, unfulfilled promises and the sheer incompetence of the state in managing water and its supply in India. There are delightful stories on how private solutions like bottled water (Bisleri), RO purifiers and overhead water tanks (Sintex) emerged to fill in for the state. But these have further exacerbated the class divide leaving a large section of the population in abject ‘water poverty’. The Niti Aayog’s Composite Water Management Index 2018 report that the book quotes sums up the water crisis in India:

“India is currently suffering from the worst water crisis in its history. In its review of states across nine broad sectors of water management, it found 60 per cent of the states, home to over half the 1.3 billion populace, performing poorly. Elaborating on the crisis, it presented a shocking parade of facts – 600 million people face high to extreme water stress; about two million people die every year due to inadequate access to safe water; twenty-one cities, including Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad, are expected to run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting 100 million people; 75 per cent of households do not have drinking water on premise; 84 per cent of rural households do not have piped water access; 70 per cent of our water is contaminated; India is ranked 120 among 122 countries in the water quality index.”

Now think of the proposed RO purifier ban. Instead of using the scarce state capacity that we have to solve the acute water crisis described above, we are going to expend capacity on regulating a water purifier ban. Does the ban address the reason why we have the biggest market for water purifiers in the world? The answer is no. Yet, instead of solving for the root cause of the problem, we are redressing the symptoms. This is the kind of misguided overreach that has rendered the state ineffective to solve the problems of basic governance. The state spreads itself so thin it has no agency and it becomes invisible to people.

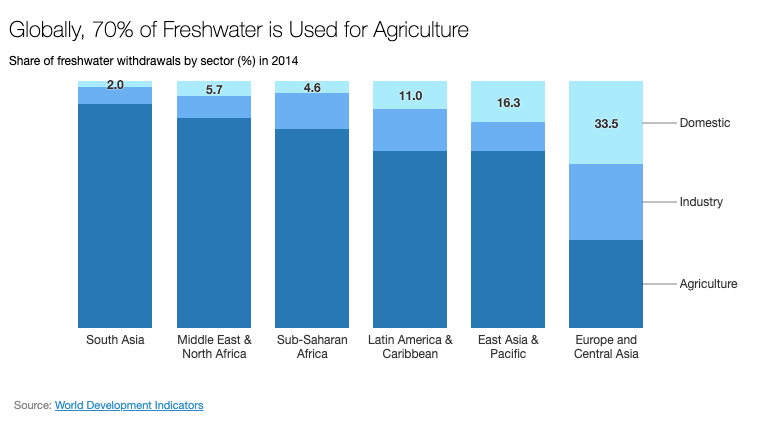

Let’s give this good-intentioned policy benefit of the doubt. Assume the whole of India stops using RO purifiers. Would we have solved India’s water problem? The answer is no. Look at this chart from the World Bank Blog.

Domestic consumption accounts for 2 per cent of all freshwater consumption. A minuscule amount of that 2 per cent would be ‘wasted’ by RO purifiers. Imagine, we are trying to put in a regulatory mechanism to fix this minute problem. I now understand what the idiom ‘missing the wood for the trees’ means.

Bans Never Work

Some of you may argue we shouldn’t conflate the two problems. That two wrongs don’t make a right. We should still support a ban on RO purifiers. We disagree. The ban won’t be effective because the weak state won’t be able to enforce it. It will create newer problems. The problems of implementation are staring at us.

The first problem is in defining which locations have TDS of less than 500 mg/l in our cities and towns. Almost every city or town in India now depends on private water tankers run by what’s called the ‘tanker mafia’ for its water needs. So, you might live in say, Koramangala, Bangalore that might have TDS below 500 but the tanker supplying to your housing complex might be sourcing its water from a location that has TDS above 500. So, what should you do? Trust the tanker water and drink it directly because RO purifiers are banned in your locality? This will just add more misery to citizens.

Secondly, the manufacturers will continue to make the RO purifiers because there’s a market for them in areas with TDS greater than 500 mg/l. So, these purifiers will be available in the market. Will the government then do a house-to-house inspection to find who is installing these purifiers in a location where it is banned? Or, will the manufacturer or the retail outlet ask you for a home address proof before selling a purifier? Who will monitor them? This Russian nested-dolls of one entity monitoring another which in turn is monitored by a third is a never-ending spectacle in Indian public life. Airport security checks are a great example of this.

Thirdly, in locations that have a TDS greater than 500, the RO purifiers will continue to be used and the water wasted. How does a partial ban help? What’s the net water savings here?

Why Such Policies?

This brings us to the next set of questions. Why then do we have this ban? Who mooted it? And how could it have been passed?

Shruti Rajagopalan and Alex Tabarrok in their latest paper – Premature Imitation and India’s Flailing State – offer some answers. They argue Indian elites love to imitate the more developed countries in adopting sophisticated policies that have limited benefits in a country at India’s stage of development. This leads to an already weak state saddled with a premature load. They illustrate this with four case studies – maternity leave, housing, open defecation and education – where we seem to be aiming for a higher rung of the policy ladder while not being equipped with the initial rungs. As they write:

“As a result, the Indian elite initiates and supports policies that appear to it to be normal even though such policies may have little relevance to the Indian population as a whole and may be wildly at odds with Indian state capacity.”

“This kind of mimicry of what appear to be the best Western policies and practices is not necessarily ill intentioned. It might not be pursued to pacify external or internal actors, and it is not a deliberate attempt to exclude the majority of citizens from the democratic policy-making process. It is simply one by-product of the background within which the Indian intellectual class operates.”

The efforts by the NGOs to ban RO water purifiers seem to be animated by these imitation instincts. It is well-intentioned but irrelevant.

The Same Old Story

So, what we will end up with is what Shankkar Aiyar hammers away in his book. The state will struggle to regulate the ban, the domestic and commercial users will find private alternatives to circumvent the ban, the manufacturers will struggle with additional state intervention and there will newer opportunities for rent-seeking by officials who will monitor, inspect, certify and apply fines.

Nothing will change – the amount of water wasted in India, the scarcity of water for people who can’t afford bottled water or a purifier, the continued dependence on water mafia in cities who have political patronage and the annual cycle of droughts and floods in India. The citizens will continue to secede from the state to their gated mini republics.

All because the state loves to solve problems it can. Instead of those it must.

p.s: The genre of “Republic as an adjective” books from India: Malevolent Republic, Brainwashed Republic, Righteous Republic, First Republic, Republic of Caste, Republic of Religion, Republic of Rhetoric, Republic of Hunger, Flailing State – you get the picture. Maybe one day we will have Arnab Goswami writing a meta-narrative of India after 2020 titled ‘Republic of Republic.’ I will buy it to test for Fahrenheit 451.

India Policy Watch: How (Not) To Encourage Digital Payments?

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

The issue of zero Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) came up a few days back at Global Fintech Fest. Merchant Discount Rate or MDR is the rate (processing fee) charged to a merchant (seller or the service providers) to assist the transactions made via credit or debit cards.

During a panel discussion on stable MDR regime at the Fest, Dilip Asbe, MD and CEO, NPCI brought up the need for a ‘reasonable MDR’:

“A reasonable MDR is necessary as it funds the acquiring systems which are responsible for deploying the system…20-25 basis point cost on the acquiring side for reasonable service… We have been trying to work to see what is possible. MDR is the only revenue for the ecosystem. We are reviewing with the government whether it is possible to bring back MDR in an appropriate way.”

Niti Aayong CEO, Amitabh Kant, also chipped in during a discussion with PhonePe CEO Sameer Nigam:

“We, in the government want to hear from the industry about the road ahead. If you tell us, we'll listen and take up the issue.”

On Jan 1, 2020, the government waived the MDR (Merchant Discount Rate) charges for transactions through homegrown RuPay and UPI platforms. Further, the government through the Department of Revenue made it mandatory for all companies with more than Rs 50 Crs in annual sales to provide for the facility of payment through RuPay debit card and UPI QR code to their customers. These steps were meant to reduce cash transactions and encourage digital payments. This was to be done within 30 days of the notification failing which a fine of Rs 5000 per day will be charged on these companies.

A ban and a good fine all in a single elegant move.

Follow The Money (And The Information)

Let me back up a bit and give you a quick run-through of how cash and payments work. First thing you must know is payment is the highest used financial transaction. You earn money in big, chunky transactions (salary, bonuses, payouts for trolling etc) and you spend them over many transactions of varying value. Now, the traditional method of payment in India was cash. Cash has many advantages – you settle the transaction immediately, it leaves no trail so your privacy is protected (useful for blackmailers, of course, but also for ordinary reticent people like me) and it doesn’t require any investment in a device or tool to use it except a wallet.

However, it has its drawbacks. It is costly to print cash, to manage its circulation and to reconcile it in a country as large as ours. Rough estimates indicate it could be costing the RBI as much as Rs 26,000 Crs to run the cash economy. Cash is often used to evade taxes and to avoid formal accounting trail by businesses leading to loss of revenues for the government. Besides, cash has other transaction costs – of carrying it, of having the right denomination to transact and safety issues. You can’t blame any government to encourage digital transactions over cash. Having said this, beyond a point, the government shouldn’t intervene to tilt the balance away from cash. The question is whether a ban on a charge the right policy intervention to support digital payments.

Now, what happens when you go to a shop (also called a Merchant) and purchase that slim-fit shirt that’s not meant for you using your debit card from a bank (also called the ‘Issuing Bank’)? You will notice there’s a POS (point of sale) machine that’s used to swipe your card. This POS machine is often provided by a Bank (called the Acquiring Bank) or a payment service provider (or Aggregator). The installation and maintenance of the POS and sundry expenses like the paper rolls are provided by them. This is a significant cost. India has over 65 million merchant establishments and only 4 million have a POS machine. These 4 million have been provided by these acquiring banks without any one-time charge to the merchant. Once you swipe and you authenticate yourself, the transaction is successful, and you are invoiced.

How The Gears Move

Here’s what happens in the background. The information about your transaction will lead to your issuing bank being debited that amount which will then be transferred to the acquiring bank’s or the aggregator’s nodal account. This is a central account and then the acquiring bank or aggregator will transfer that information to the merchant’s account that’s with the bank or with the aggregator.

Once this information reaches the merchant bank account, the merchant receives the information that the money has reached them. This information exchange happens in real-time. There are payment networks like Visa, Mastercard and the homegrown RuPay that facilitate this information flow. The actual money transfer happens over the next 2-3 days and the merchant receives the money in their bank account.

This whole process requires physical and technology infrastructure, network, authentication services, security, multiple players who specialise in different parts of this chain and at least 2 banks (Issuing and Acquiring Banks) involved who transfer money among themselves at a rate called Interchange rates. Plus, there are other costs in case there are wrong transactions, refunds or chargebacks etc.

In India, we decided a few years back, the cost of these transactions as a charge can’t be levied on the customer. So, the acquiring bank (or an aggregator working on its behalf) started charging a fee to the merchant called the Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) for all the services it provides. Typically, it ranged between 1-3% for a transaction. The merchants were fine with it since it reduced the ‘friction’ in dealing with a customer, eliminated their cash-carrying costs, improved security and brought down cash pilferage. Of course, there were merchants who wouldn’t want to go digital because of their aversion to being in the formal economy that’s transparent. That aside, this seems like a win-win and so long as market forces played out on the MDR charges you could apply, no single bank could keep hiking MDR rates. This is how it plays out in the rest of the world.

What we have established so far is there are costs of running the digital payment ecosystem. These costs are borne by multiple specialists who participate and play specific role in the information and the money flow. The MDR is a charge levied to the merchant by the acquiring bank for these services. The acquiring bank then splits this MDR charge among these players to keep them viable and interested in delivering these services. God’s in his heaven and all’s well with world like Browning would have said.

Right? Wrong.

Enter Good Intentions

There was this growing feeling that MDR rates are being baked into the price of the products by the merchants. There’s no way to know this. And, surely a lot of us as customers don’t really make out if there is a higher price to pay because of digital payment in most cases (barring those small merchants who charge an extra fee for usage of a card). There was also a view that the MDR charge was significant for some merchants and dissuaded them from pushing customers towards digital transactions. This built momentum to the idea that if you eliminate MDR, the merchants will have greater incentive to go digital and they will pass the savings of MDR to the customers with lower prices. This will lead to customers doing more digital transactions.

The government did two things in parallel. They made it mandatory for any merchant with more than Rs 50 Crores in revenue to enrol into RuPay or BHIM UPI as a platform. RuPay is a government-owned payment network owned by NPCI while BHIM UPI is a government-created utility. And they abolished MDR for RuPay and BHIM UPI.

How will this play out?

First, MDR charges were bringing RuPay and Bhim UPI almost Rs 1800 crores of annual revenues. This will disappear. The FM’s view was “RBI and banks will absorb these costs from the savings that will accrue to them on account of handling less cash as people move to these digital modes of payment.” This will be true in the long run if this move truly pushes digital transactions significantly higher. We will come to that later. But in the short run annual revenues of Rs 1800 crores is lost to the government.

Second, merchants will now have an incentive to push RuPay card usage over other cards. Visa and Mastercard can’t make their charge zero since it is their primary source of revenue. Government is a regulator and a player in this industry. This skews the playing field in favour of NPCI – an entity owned by the government. Also, how do we know if the merchants have passed on the benefit of zero MDR to customers by reducing the price of their products? So, the end customer benefits remain dubious.

Third, the merchants pushing for RuPay would mean the acquiring bank will make no money on a transaction since MDR is zero. The acquiring banks (or the aggregators and payment service providers) have been responsible for making the small shops and vendors across India go digital by installing the POS machines and running them in their premises. This requires a large team that serves thousands of shops in small-town India and convinces them to go digital with POS machines, QR codes, app downloads etc.

RuPay doesn’t do this. It is not in this business. But with zero MDR, banks won’t do it either. So, in the absence of any incentive, who will do this now? Who will maintain the 4 million POS machines in the market already if there’s no money to be made running them? How will we go from 4 million to 65 million shops going digital? Who will make these investments? Who will continue to innovate on the payment ecosystem and make it more frictionless and easier for customers and merchants? What’s the incentive for fintech players to help SMEs and MSMEs to go digital and manage their financial and treasury operations?

Anticipating the Unintended

Here’s what will most likely happen. Banks will make up the loss in revenues through some other charges they will add to their services elsewhere. This will be higher than MDR and it will be borne directly by customers. Or they will withdraw rewards scheme or free services they used to offer customers to recover the revenues. There won’t be any incentive to add new POS across the country. The attractiveness of the payment ecosystem for innovative entrepreneurs will wane.

It is useful at this point to see how a similar move played out in the US. Right after the 2009 financial crisis, the US enacted the Dodd-Frank law that laid out various new regulations to rein in the financial services sector. The Durbin amendment was part of this law which aimed to lower the interchange fees (the charges that merchants pay to banks when a customer makes a purchase; their version of MDR) with a view that this would lead to merchants passing the savings to the customers in lower prices and reduce the money the big banks made. So, there was an upper cap fixed for the interchange rate that a bank could charge the merchant. There was no ban, just a price ceiling. A lesser evil on the ladder of government interventions.

After 8 years of this amendment, it is instructive to see how this played out based on various studies done. First, the big banks recouped their loss in revenues by increasing customer fees and reducing rewards elsewhere. A study by George Mason University found the retail prices haven’t come down at all. So, merchants didn’t really pass on the benefits to customers.

Most interesting though was the impact of this on small retailers like coffee shops, delis, small merchants. In the earlier regime when there was no price cap, the bank would charge a much lower rate for smaller value transaction while charging full rates for a high-value transaction. This was a form of price discrimination to maximise the full potential of digital payments. So, for example, in the pre-Durbin regime, the charge would be 44 cents for a typical $ 44 transaction while they would charge 3 cents for a $ 4 transaction. In the post-Durbin world, the interchange charge on a $ 44 transaction was capped at 26 cents (losing 18 cents from pre-Durbin era). This meant that the Bank would charge the $ 4 transaction now at 21 cents instead of 3 cents (recouping the 18 cents lost). So, the smaller retailers who had smaller value transactions were left with a distinct disadvantage and they started discouraging digital payments. In summary, no one was left wiser if the Durbin amendment helped anyone.

Nobody Loves A Good Ban

The Indian MDR rates were already among the lowest already in the world. The MDR rates are not the only reason for lower digital adoption. We need to increase the coverage of POS machines to more merchants and we need to strengthen GST and tax compliance practices to have more merchants adopt digital payments. Possibly, a better policy alternative would have been to have a slab based MDR that was lower than the current rates and provided a tax incentive for the digital part of revenues declared by the merchants. That would have kept the incentive for payment players to continue building payment infrastructure across the country while giving a direct benefit to merchants to go digital.

The current approach reduces choice for the merchants and skews them towards a particular player (RuPay), increases the market concentration risk and the systemic risk in case of security failure or large outage at RuPay. It provides no incentive to anyone who wants to pound the streets of Bharat to get merchants on the digital train and provide innovative products and solutions for them.

Like most bans, this might deliver a few short-term gains. But the unintended consequences in the long-term will hurt the objective of increasing digital payment transactions.

The industry has taken seven months to find its voice to oppose this. At least, that’s a start.

A Framework a Week: Why Large WhatsApp Groups Are So Ineffective?

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

The framework that I’m discussing today is based on a 55-year old book. Yet it can explain why large groups of any kind (particularly those on Facebook or WhatsApp) descend into raucous discussion boards and fail to galvanise members into action towards achieving a collective good.

You have a large WhatsApp apartment group and the road outside your apartment is broken. It’s in every resident’s interest to get the road repaired. And yet, you fail to mobilise enough people to act in substantive ways to get this done. Sounds familiar? But why does this happen?

Mancur Olson, an economist, in his book The Logic of Collective Action hypothesised that small groups differ from the large ones not just quantitatively but also qualitatively. Even if the end result of an action might be beneficial for all members of a group, the propensity of every member to act depends on the per capita benefits accruing to her alone. Olson writes:

“..in a large group in which no single individual's contribution makes a perceptible difference to the group as a whole, or the burden or benefit of any single member of the group, it is certain that a collective good will not be provided unless there is coercion or some outside inducements that will lead the members of the large group to act in their common interest.”

In other words, the pursuit of a collective good depends on whether the contribution (or the lack of it) of one individual will have a noticeable effect on the costs or benefits of other individuals in the group. The larger the group, the lesser the chances of this effect being noticeable, hence lesser the chances of success. Free-riding is easier when groups are larger.

Olson provides three reasons that prevent even large groups from furthering their own interests:

The larger the group, the smaller the fraction of the total group benefit any person acting in the group interest receives, and the less adequate the reward for any group-oriented action, and the farther the group falls short of getting an optimal supply of the collective good, even if it should get some.

Since the larger the group, the smaller the share of the total benefit going to any individual, or to any (absolutely) small subset of members of the group, the less the likelihood that any small subset of the group, much less any single individual, will gain enough from getting the collective good to bear the burden of providing even a small amount of it.

The larger the number of members in the group the greater the organization costs, and thus the higher the hurdle that must be jumped before any of the collective good at all can be obtained.

Can large groups ever be spurred into action?

Olson says that a separate and selective incentive is a necessary condition for getting a rational individual in a large group to act in a group-oriented way. Separate in the sense that the potential benefits that the collective good might provide are not good enough by themselves to stimulate action. So, saying that repairing the road will be beneficial to everyone is not sufficient to get an apartment group to act. Selective in the sense that those who act in the group’s interest need to be rewarded. Or those who don’t, need to be penalised. In other words, perfectly democratic groups are also ineffective groups. Moderation in the form of rewards and punishments is necessary.

Here’s my summary: there is merit in having smaller action-oriented groups. Membership of groups that aim towards ‘getting something done’ needs to be kept selective. For larger groups, a separate incentive mechanism needs to be devised to make individual contributions noticeable — something that doesn’t happen on WhatsApp or Facebook groups. Free for all groups with weak moderation are least likely to get things done.

Matsyanyaaya: Mythicising China’s strategic behaviour

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

Because we don’t understand China’s strategic priorities well enough, we often resort to historical antecedents, writings, even quotable quotes (remember Deng Xiaoping’s “lie low”?), to explain China’s strategic behaviour. This reductionist tendency is no longer the preserve of the non-Chinese. Chinese strategists themselves selectively pull out cultural myths that can project China as an eternally peaceful and responsible global power. Strategic culture myths serve another function: when on the backfoot, Chinese strategists often use cultural myths to imply that China has a totally different perspective on war and strategy that the West is incapable of understanding.

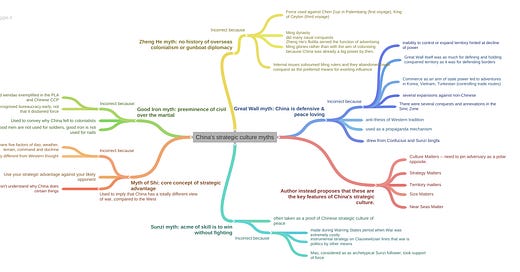

Given how frequently strategic culture myths are used in the Chinese context, I was delighted to read the chapter “Myth busting: challenging the conventional wisdom on Chinese strategic culture” by Andrew R Wilson, professor of strategy at the US Naval War College. The book is a Routledge edited volume titled China’s Strategic Priorities (ed. Jonathan Ping and Brett McCormick). The author identifies five myths that are believed to be the core elements of China’s strategic culture — the Great Wall myth, the Sunzi myth, the Good Iron myth, the Zheng He myth, and the myth of shi.

In the author’s words,

“these myths enjoy little historical basis and even less explanatory power for understanding contemporary Chinese strategy. At best they are reductionist and misleading. And yet these five myths in their various forms and combinations continue to dominate today’s discussions of Chinese strategic behaviour [China’s strategic priorities, page 8].”

I found this dismantling of China’s strategic culture myths very useful and constructed a mind map that can help China watchers (click here to expand). Maybe this will be instrumental in diffusing the myth-making surrounding China’s strategies.

Based on “Myth-busting: challenging the conventional wisdom on Chinese strategic culture” by Andrew R Wilson (click here to expand)

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] Professor Stebbing (Imperial College, London), who recently published in The Lancet new research on using AI to find drugs to treat COVID-19, talks about COVID-19 vaccine timelines and other insights from infection data

[Paper] Covid-19 and Corporate India by Aakriti Mathur and Rajeswari Sengupta in the Leap Journal where the authors present their findings on the type of firms that have the maximum exposure to the pandemic.

[Video] A discussion on global prospects for liberalism moderated by Yascha Mounk with three international members of Persuasion’s Board of Advisors: Denise Dresser, Ivan Krastev, and Pratap Bhanu Mehta.

That’s all for this weekend. Read and share.

If you like the kind of things this newsletter talks about, consider taking up the Takshashila Institution’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy (GCPP) course. It’s fully online and meant for working professionals. Applications for the August 2020 cohort are now open. For more details, check here.