Programming Note: A lighter edition this weekend because life happened of late-night football, missed flights, and several other things. Also, we will be away for a short year-end break. Normal service will resume on Jan 8, 2023.

Happy holiday season, everyone!

India Policy Watch: Digital Rupee (e₹-R) Is In Town

Insights on current policy issues in India

— RSJ

The RBI launched the first pilot for the retail digital Rupee this week. It is now among the select list of central banks that’s got a CBDC pilot going.

The RBI press release covers the plan for the pilot:

The pilot would cover select locations in closed user group (CUG) comprising participating customers and merchants. The e₹-R would be in the form of a digital token that represents legal tender. It would be issued in the same denominations that paper currency and coins are currently issued. It would be distributed through intermediaries, i.e., banks. Users will be able to transact with e₹-R through a digital wallet offered by the participating banks and stored on mobile phones / devices. Transactions can be both Person to Person (P2P) and Person to Merchant (P2M). Payments to merchants can be made using QR codes displayed at merchant locations. The e₹-R would offer features of physical cash like trust, safety and settlement finality. As in the case of cash, it will not earn any interest and can be converted to other forms of money, like deposits with banks.

The pilot will test the robustness of the entire process of digital rupee creation, distribution and retail usage in real time. Different features and applications of the e₹-R token and architecture will be tested in future pilots, based on the learnings from this pilot.

The obvious question that comes up is how’s a digital currency different from a transaction on UPI. The RBI Governor got into the explanation mode on this at the press meet.

Separately, in an earlier concept note, the RBI had outlined the two different types of CBDC it would pilot as part of this process:

Based on the usage and the functions performed by the CBDC and considering the different levels of accessibility, CBDC can be demarcated into two broad types viz. general purpose (retail) (CBDC-R) and wholesale (CBDC-W).

CBDC-R is potentially available for use by all private sector, non-financial consumers and businesses. In contrast, wholesale CBDCs are designed for restricted access by financial institutions. CBDC-W could be used for improving the efficiency of interbank payments or securities settlement, as seen in Project Jasper (Canada) and Ubin (Singapore). Central banks interested in addressing financial inclusion are expected to consider issuing CBDC-R.

Further, CBDC–W has the potential to transform the settlement systems for financial transactions undertaken by banks in the G-Sec Segment, Inter-bank market and capital market more efficient and secure in terms of operational costs, use of collateral and liquiditymanagement. Further, this would also provide coincident benefits such as avoidance of settlement guarantee infrastructure or the need for collateral to mitigate settlement risk.

About 18 months back, in edition #122, I wrote a fairly detailed piece about CBDC in the context of China running a pilot for digital Yuan. It will be useful to bring that piece up to contextualise the RBI CBDC pilot.

What’s Money?

As we have written in an earlier post, money performs three roles for us: it is a store of value, it is a medium of exchange, and it is a unit of measure. Through it, we save for the future, pay for goods and services and measure the value of very different things using a common unit. These roles mean anything that aspires to be a currency (the usable form of money) should have a relatively stable value over time and should be widely acknowledged as a store of value and unit of account among people. If it does so, the network effect takes over after a while, and it becomes a widely used currency.

Throughout history, a key feature of a sovereign state was its control over the supply and circulation of money that’s used within its boundaries. The royal mints, after all, have been around for more than two thousand years. As modern nation-states emerged through the 19th and 20th centuries and as global trade increased, central banks emerged to manage the monetary system and provide financial stability.

There are three forms of money in any modern economy:

Banknotes: These are physical paper currency notes issued by the central bank that we all use in our everyday lives. This is a direct promise by the central bank to pay the note holder a specified sum of money. This promise is printed on all currency notes.

Bank Deposits: Ordinary people and businesses don’t hoard banknotes to conduct their business. They deposit their money in commercial banks. These deposits are stored in electronic form by these banks. The banks offer two services to their customers. They convert these deposits to central bank money in the form of banknotes when you demand it at an ATM and they offer to transfer your money to someone else through a payment system that exists between banks. Unlike banknotes, your deposits aren’t risk-free. They aren’t backed by any sovereign guarantee. A bank will be able to convert your money into banknotes only if it is solvent and can honour its commitments. We have seen instances of a bank failing to do so in India (Yes Bank, PMC etc.).

Central Bank Reserves (“reserves”): Commercial banks have their own accounts with the central bank where they deposit their funds. These deposits are used by banks to pay each other to settle transactions between them. The reserves are the other form of central bank money apart from banknotes. These are risk-free and therefore used for settlements among commercial banks.

Where does CBDC then fit in?

Simply put, a CBDC is a digital form of a banknote issued by the central bank. Now you might think we already use a lot of digital money these days. Yes, there’s money we move electronically or digitally between banks, wallets or while using credit/debit cards in today’s world. But that’s only the digital transfer of money within the financial system. There’s no real money moving. The underlying asset is still the central bank money in the form of reserves that’s available in the accounts that commercial banks have with the central bank. This is what gets settled between the commercial banks after the transaction.

This is an important distinction. We don’t move central bank money electronically. But CBDC would actually allow ordinary citizens to directly deal with central bank money. It will be an alternative to banknotes. And it will be digital.

CBDC: The Time Is Now

So, why are central banks interested in CBDC now?

There are multiple reasons.

One, cryptocurrency that’s backed by some kind of a stable asset (also called ‘stablecoin’) can be a real threat as an alternative to a sovereign currency. Stablecoins are private money instruments that can be used for transactions like payments with greater efficiency and with better functionality. For instance, the current payment and settlement system for credit cards in most parts of the world has the merchant getting money in their bank accounts 2-3 days after the transaction is done at their shops. A digital currency can do it instantly. For a central bank, there could be no greater threat to its ability to manage the monetary system than a private currency that’s in circulation outside its control.

Two, in most countries, there’s an overwhelming dependency on the electronic payment systems for all kinds of transactions. As more business shifts online and electronic payment becomes the default option, this is a serious vulnerability that’s open to hackers and the enemy states to exploit. A CBDC offers an alternative system that’s outside the payment and settlement network among commercial banks. It will improve the resilience of the payment system.

Three, central banks need to offer a currency solution for the digital economy that matches any form of digital currency that could be offered by private players. Despite the digitisation of finance and the prevalence of digital wallets in the world today, there’s still significant ‘friction’ in financial transactions all around us. You pay your electricity bill electronically by receiving the bill, then opening an app and paying for it. Not directly from your electric meter in a programmed manner. That’s just an example of friction. There are many other innovations waiting to be unleashed with a digital currency. Central banks need to provide a platform for such innovations within an ecosystem that they control. CBDC offers that option.

Lastly, digital money will reduce transmission loss both ways. Taxes can be deducted ‘at source’ because there will be traceability of all transactions done using CBDC. It will also allow central banks and the governments to bypass the commercial banks and deliver central bank money in a targeted fashion to citizens and households without any friction. The transmission of interest rates to citizens for which central banks depend on commercial banks could now be done directly.

While these are the benefits of a digital currency, there are other macroeconomic consequences including the loss of relevance of bank deposits that we have with our banks. Some of these may seem speculative at the moment but these are factors to consider as things move forward. A CBDC that offers interest will mean we could have a direct deposit account with the central bank. This will also mean a move away from deposits in banks to CBDC with the central bank. Also, the nature of a bank ‘run’ will change. Today a bank ‘run’ means a rapid withdrawal of banknotes from a bank by its depositors who are unsure of the solvency of the bank. This takes time and is limited by the amount of money available in ATMs. In a CBDC world, the ‘runs’ will be really quick and only constrained by the amount of CBDC issued by the central banks. Depositors will replace their deposits with CBDC pronto.

This secular move away from deposits could increase the cost of funds of commercial banks. They will have to depend on other sources of funds than the low-cost deposits that customers deposit every month in the form of salaries to them. A reduction in deposits will reduce the availability of credit in the system. This will have a repercussion on the wider economy. It will also mean greater demand for reserves from the central bank by the commercial banks to provide credit to their customers. Central banks will increase their reserves and their balance sheets will become bigger. These are among many potential scenarios that could unfold. These are early days and it will be interesting to track the iterations of the pilots that the RBI will do as it appreciates the use cases, the design features and the policy issues involved.

This is an interesting space to watch. India’s track record on building national digital infrastructure in payments is second to none. It might be the one place where the promise of CBDC could turn into reality.

A Framework a Week: China’s Predicament

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

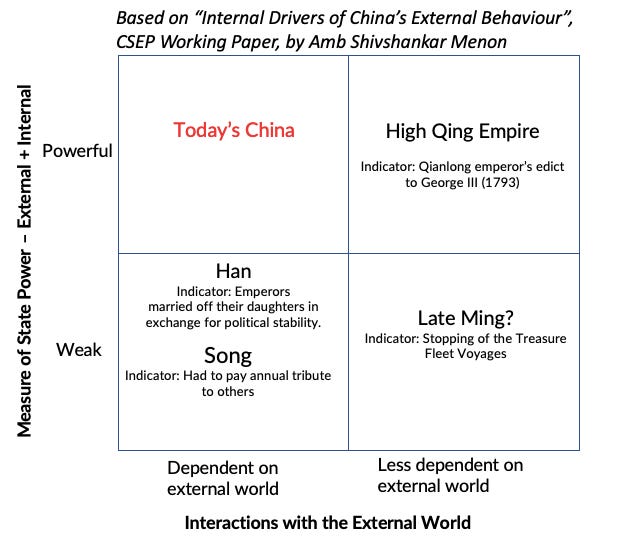

A couple of weeks back, I had linked out to a CSEP paper by Amb. Shivshankar Menon. Titled Internal Drivers of China’s External Behaviour, he explains the domestic imperatives that are likely to modify China’s external behaviour.

In that paper, one #lightbulb framework explains the novelty of the situation that China finds itself in. Here’s the text from the paper:

Today, China faces an unprecedented situation at home and abroad and is therefore reacting in new ways. China is more powerful than ever before but is also more dependent on the world. This is an unprecedented combination, not known in Chinese history—not in the Han when she had to ‘buy’ off the Xiongnu by marrying Han princesses off to steppe leaders; nor in the Song when she was one and sometimes the weakest power in a world of equals; nor in the high Qing when she was powerful but independent of the external world, as the Qian Long emperor reminded George III in writing. [Internal Drivers of China’s External Behaviour, CSEP Working Paper, Shivshankar Menon ].

We can interpret this insight visually in this 2x2 framework.

The implication is that China finds itself in an unfamiliar position today and as a result, will act externally in new ways altogether. The high power-high dependence combination helps explain China’s belligerence in the Himalayas and the South China Sea.

It also explains the drive towards self-reliance in technology domains. The high-dependence on adversaries acts as a motivation, and high domestic power gives China the confidence (over-confidence?) to do it all domestically. Observe China’s response to the US export controls on its semiconductor industry. I expected a definitive retaliation after the 20th Party Congress had reaffirmed Xi’s control. But that hasn’t happened. It only makes sense if China’s political establishment is confident of overcoming the dependence in due course while taking advantage of it to bolster present capabilities.

Advertisement: Takshashila is now accepting applications for the next cohort of GCPP. Apply now. If you like reading this newsletter, you will find the course enriching.

PolicyWTF: Emigration Embargoes

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Pranay Kotasthane

Rina Agarwala has an excellent article in The Monkey Cage, highlighting the restrictions preventing the less-educated, poor Indians from emigrating easily.

“Under India’s 1983 Emigration Act, poor emigrants have to hire a government-certified recruiter, fill out piles of government paperwork, pay huge fines and hope for government approval. Unlike Ramdas Sunak’s experience in the 1830s, they usually emigrate without family members on temporary visas, working under difficult conditions for little pay under the control of their foreign employer.

Although these emigrants send home the largest share of India’s massive remittances — an estimated $100 billion in 2022, and which have saved India through multiple financial crises and cover 40 percent of the basic needs for millions of poor households — they receive little acknowledgment or support from the Indian government.

Educated emigrants, by contrast, are free to leave India as they please. Since the 1980s, the Indian government has offered them awards and special financing options for savings accounts, investments and bonds within India. The government has also encouraged their temporary return to India with business partnerships and high-level positions within the Indian government. Receiving countries are also more likely to welcome educated Indians than poor immigrants. [Is the new U.K. prime minister a paragon of immigrant success?, Rina Agarwala, Washington Post]

It is indeed quite disturbing how the emigration policy came to be this way. There are good intentions behind it, of course. The government’s rationale is that these entry barriers are meant to check human trafficking. That’s why the restrictions on less-educated women are even more stringent than those for men. Check this out:

The Emigration Act (1983) states that persons of working age who have not completed schooling up to the tenth standard are issued an ECR (Emigration Clearance Required) passport. The remaining population is eligible for an ECNR (Emigration Clearance Not Required) passport. When men having ECR passports plan to emigrate for work, they need to obtain an “Emigration Clearance” from the office of the Protector of Emigrants (PoE) before travelling to certain countries (currently, 18 in total). What’s even more egregious is that a woman of age less than thirty with an ECR passport is completely banned from getting emigration clearance for all kind of employment in any ECR country.

But the anticipated unintended result is that it blocks off opportunities for people who probably would improve their life outcomes the most by emigrating.

I’ll leave you with a link to edition #15, in which we write about this policyWTF and solutions to improve the situation.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] Our Puliyabaazi on public libraries received a lot of listener interest. What do you make of it?

[Book] Global Value Chains and the Missing Links: Cases from Indian Industry by Saon Ray and Smita Miglani is a must-read to understand India’s prospects in different sectors, given the shifting geopolitics and geoeconomics.

[Podcast] Math with CCP Characteristics.

Share this post