We have a book out. Already bought it? Good.

It makes for a great gift too. Ship it to your friends. Here’s the helpful link.

Now curl up for a long Sunday edition.

India Policy Watch #1: The State and Capital

Insights on current policy issues in India

— RSJ

The Indian equity markets have been hit by a research note on the Adani Group, the diversified conglomerate with interests ranging from ports to vanaspati. The group, whose market cap was a little over ₹21 trillion (~ $250 billion) at the start of the week, lost about 20 per cent in two trading sessions, based on the report. Maybe you’re feeling a little sorry for the group’s fortunes on the back of the note.

Don’t.

This might give you some perspective.

“The combined m-cap of Adani group companies was up 66 per cent during the 2022 calendar year; the group gained 82.8 per cent in CY22 if we add the listing of Adani Wilmar and the acquisition of Ambuja Cement, ACC, and New Delhi Television. The group ended CY22 with a market value of Rs 21.3 trillion, up from Rs 11.64 trillion at the end of December 2022. The group bought Holcim India assets in May last year and acquired NDTV from its promoters in November last year.

In all, the Adani group m-cap was up 419 per cent between January 2020 and December 2022, from Rs 4.1 trillion to Rs 21.3 trillion. After Friday’s fall, its m-cap is the lowest since March 2022.” [Business Standard]

Heh!

What’s a 20 per cent fall when you’ve had a 419 per cent (missed by 1 per cent there) rise in about 3 years? And if one were to stretch the timeline a bit further, in 2013, the group was valued at ₹50,000 Crs or ₹0.5 trillion. From 0.5 trillion to 21 trillion in a decade. You do the math. Or maybe I will do it for you. That’s about 4100 per cent. If you wrote a film script about this, studio execs would have asked you to tamp down on the fantasy bit.

There are three areas to go deeper into as we look at this minor blip in the Adani saga. And yes, it will be a minor blip, all things considered. One, trying to make sense of the Hindenburg note and its likely repercussions on the group and Indian markets in general. Two, how should one think of policymaking in areas like infrastructure and utilities that tend to have monopolistic features? And lastly, what does all of this tell us about the relationship between Indian capital and polity?

About The Note

So what’s the gist of the report and the 88 questions Hindenburg has posed to the Adani Group? Hindenburg is an activist short-selling firm that sells borrowed stocks today with a commitment to buy them at a price in future. They borrow it from long-term investors who believe in the stock's prospects. If the price falls in future, the short sellers make a profit. Typically, such firms pick stocks that they believe are overvalued on fundamentals or have a flaw in their business model. They then push the narrative that the stock needs to be re-rated. They would have already built positions in advance of such a narrative. If the narrative succeeds, the stock tanks temporarily, and the short seller makes a quick killing.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with this. Short selling has a role to play in the markets. It increases liquidity, deflates bubbles, brings fraudulent or delusional business models into focus and provides good entertainment to bystanders. All good stuff. Efficient markets and all that. They also earn the justifiable ire of companies that don’t have any of these features but are simply stuck in a bad business phase. Their lives are made worse because of short sellers. It isn’t surprising, then, that they are seen as vultures preying on firms in duress. But short sellers take such brickbats as occupational risks. In their world, they are investigative investors who love exposing fraudulent corporations and calling out scams.

Hindenburg is a relatively new and characteristically aggressive member of this species. They have had a good track record in running down the likes of Nikola - remember the Tesla of trucks that made unverifiable claims which all turned out to be false? Famously it played a promo video showing a Nikola EV truck cruising at high-speed while, in reality, it was just a truck being rolled down a hill in Utah, a bullshit claim Hindenburg exposed. The valuation of Nikola went down from $ 34 billion at its peak to about a billion now. There are other scalps that it has had - Bloom energy, China Metal, HF foods etc., all of which have been followed up with regulatory action. This isn’t a random operator who has surfaced with a series of allegations. They have a track record of questioning the valuations of companies.

So how does Adani fare in being in the crosshairs of Hindenburg? Do they deserve to be there?

Listen, anyone running up a 419 per cent increase in valuation in less than three years can be seen to be in bubble territory. There are two ways to look at this. One is that there are structural reasons that can justify this scrutiny by short sellers. This could have happened to any group with similar characteristics. What are these?

The Adani listed entities have a low free float, i.e. there is a small number of shares available in the public market to trade because, in all these stocks, the Adani family owns over 70 per cent. A low float means there aren’t many shares available, leading to low liquidity. Low liquidity means difficulty in matching demand versus supply. So any marginal increase in demand or supply significantly impacts the price of the shares. So, the volatility of such stocks is high. Simply put, when the going is good, valuations rise dramatically and get into bubble territory. It is normal for them to attract short-seller interest.

The other structural reason is the sectors in which Adani companies have built businesses. Infrastructure and utilities tend to require a high upfront investment, which typically takes the form of debt and its profits are back-ended. It is usual to see highly leveraged companies with small profits in these sectors. These projects run the risk of delays, changes in regulations or innovation that could disrupt their long-term plans. Short sellers bet on such an eventuality coming true.

Lastly, the group has diversified itself furiously in the last five years. They have their footprint across the Indian infrastructure and utilities space —ports, energy, airports, transmission, green energy, cement and many other sectors where they have unlisted entities. Considering the family’s stake in them, these are run fairly centrally with members of the family and a close circle of confidants at critical executive positions. It is difficult to run just a couple of these complex businesses well. Running so many of them at a breakneck speed requires huge management bandwidth and acumen. And luck. Maybe the group has it, but it is understandable if a short seller is sceptical about it.

Structural reasons that could apply to any group with similar underlying features aside, there are a few other reasons Hindenburg has picked up that are unique to the Adani Group. As their research has shown, there is a network of offshore shell companies that have direct or indirect interest in the group listed companies. Some of these have opaque ownership that links back to the family or have common addresses. You know, the usual playbook. Then there are governance issues laid out thick in the report - from suspicious characters running offshore businesses, sketchy audit practices covering up accounting irregularities and stock manipulation. Short sellers smell blood when they come across such things. So did Hindenburg.

The group has called these charges stale, unsubstantiated and baseless or words to that effect. There is an FPO (further public offer) that is on at the moment where the group is trying to sell ₹20,000 Crs of its shares. This is what Hindenburg has timed its report to target. The FPO might struggle a bit to sail through. But that amount is a chump change for the group. A week or so of volatility, some questions from regulators, a few lawsuits, some strategically timed PR events and the group will be done with this kerfuffle by February. This is nothing more than a minor speed bump in its fortunes.

Public Policy Questions

There is often a defence made about companies that become dominant in the infra or utilities space that the nature of these sectors is monopolistic or oligopolistic. This is true for reasons too many to go into this post. These sectors need large balance sheets, which becomes difficult for a new player or a disruptor to compete against. Also, once you’re large, you have economies of scale and network effects to dictate the price and build customer moats that are difficult to penetrate. That’s fine. Nothing illegal about it. This could hold true if, over a period of time, someone builds a dominant position in a sector. The speed with which the Adani Group has done so, across many sectors, with greenfield projects or strategic acquisitions, where they win bids with mechanistic efficiency, makes for an interesting case study.

The design of these auctions or bids and the accumulation of monopolistic market power across so many interlinked sectors is a useful public policy issue to think about. The State, instead of doing hundreds of things it shouldn’t be doing, should be working on better design of bids and controlling market failures like monopoly power building up in critical sectors. Also, it is true that many questions raised by Hindenburg have been raised in the past or are speculative in nature, but that doesn’t mean they have been answered fully. The sectoral regulators and the many institutional shareholder advisory firms that have come up in India should seek more clarity on them. The best course of action for the Group is to engage more with their stakeholders and settle these persisting questions. It will help the group in future and also restore confidence in the governance practices in corporate India for global investors. India would like to believe it is on the cusp of a golden decade. It will help if its policy response to such issues shows it is learning and evolving. But will it?

State and Capital

There are a few broader issues to think about the relationship between the State and Capital in light of this.

One, the State has disproportionate and arbitrary power in regulating sectors relating to natural resources. This means either of two things happens. The State either arbitrarily chooses winners who might not be capable of executing the work or are only in the game to take huge debt from banks (especially public sector banks), siphon off the funds and go through a convoluted bankruptcy process and come out unscathed. This has been the modus operandi for many infra projects in the past with repeat offenders. This is crony capitalism, and what’s worse, you don’t get anything at the end of it all. Nothing gets completed. This arbitrary nature of state intervention has meant our infrastructure has lagged the world and credible players have stayed from entering this sector in the last decade. Further, financial institutions have burnt their fingers and have been too careful in lending to greenfield projects. The unintended consequences have been terrible for the people who make do with some of the worst public infrastructure in the world for fast growing economy.

The other model is you choose winners, and they get things done. This is crony capitalism, but atleast you get the work done for the public at the end of it. So far, the Adani Group falls in this category which, in a strange way, is an improvement from the last infra cycle we had in 2009-13. Small mercies. Also, if we are going to be choosing some kind of national champions, it would be good to make it official with the State taking a stake in such enterprise too. Why not participate in the value you’re helping create? None of this is to condone crony capitalism in any way. It distorts the market, reduces competitiveness and makes the customers pay for poor service and high prices eventually. But in the Indian context, there’s always been someone using the State to maximise its business advantage. You know the names that have changed over the years. The model remains the same. So, you will settle for it if it delivers the service promised to start with. This isn’t how a mature State and Capital interact, but that’s where we are.

Two, there’s a long-term risk with many critical infrastructure sectors being dominated by a single group. Continuity is a virtue in these sectors, but that is at risk if it is built on the foundation of cronyism. The same party may not be in power forever. Even if it does, new players may hold the levers of power in the party in future. This could mean a reset in relationships, or newer favoured entities coming in. Unwinding investments and switching market dominance in such sectors can get messy and will disrupt the lives of citizens. That apart, there’s always the risk of second or third generations of the family splintering or lacking the management acumen of the founding group. They will flounder in running these businesses. That would again run similar risks for citizens.

Third, there are two responses from different quarters that are funny and sad in their own ways. And they tell something about the state of capital in India today. There’s one argument being made by partisans that this is some kind of western conspiracy against India to derail its infra push by torpedoing its key infra player and its FPO. It is funny because, till last year, when Indian markets were doing well and FPI and FDI were touching all-time highs, there were no conspiracies to be found. It is quite incredible how the usual Indian scepticism and distrust of the rich is now coming up short against the politics of vishwaas. Harnessed well, this change in attitude can be a game changer in how the citizens view the market. But it is being used for a different set of objectives here.

The other response, or the lack of it, is from other business houses over the years as they see a dominant player emerge in multiple sectors. They have been happy either not venturing into those businesses or finding comfortable adjacencies. This will be an interesting space to watch because it is almost certain that there will be an intrusion into their long-held territories too. The ambitions will collide. Will those silently watching so far, cede their ground and happily become a smaller player, or will they fight for their turf? It is difficult to say, but the wider silence over the years tells you all about Indian capital at this moment that you want to know.

As I said earlier, the Adani Group will find the answers to the questions posed, and this will be a minor bump on its path. The report is just that—a report. The real questions are about correcting the distorted relationship between the Indian state and markets. Of being pro-markets and not pro-business. And about creating an environment where people trust markets. Those questions aren’t getting any answers anytime soon. That’s a long haul.

India Policy Watch #2: Don’t Forget State Capacity

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

We often invoke the “lack of state capacity” when we witness policy failures. The concept helps us transcend the utter useless simplification that goes something like this “policy was good but implementation was bad”. Analysing state capacity can help us anticipate unintended consequences and help pick a context-appropriate policy instrument.

The lack of adequate state capacity can be debilitating. It weakens the State’s authority. More importantly, it shows up in unexpected ways. As in the Whack-a-Mole game, plugging one failure only means that weaknesses start showing up in other places.

So this week, I want to reflect on some domains of public policy where the Union government needs a step jump in capacity. Of course, we know there is no branch or function where the Indian State has adequate capacity. Moreover, capacity issues in the domains of law and order and enforcement are chronic and well-known. And issues such as health and education are primarily state government issues. So I’ll focus on three domains where the need for filling state capacity gaps has become urgent in recent years.

One: Foreign Policy Capacity

We are between world orders. The interregnum requires confronting tough trade-offs and making things happen. As it has become apparent, this period is a tremendous opportunity for India’s role as a global actor. India is chairing the G20 this year. It needs to get things moving in the Quad. Given that India isn’t in the new multilateral trade groupings, several bilateral trade agreements must be carved out. The Ukraine-Russia War drags on, and India has the opportunity to mediate at the appropriate time. The Indian government also wants to popularise its digital public infrastructure stack. More broadly, high technology is now a global enterprise where foreign policy will play a crucial role in enabling technology flows.

In short, foreign policy is now a high-stakes game. A lot needs to be done. But the gap between these expectations and policy capacity has only grown wider. Without increasing policy capacity immediately, these opportunities will not deliver results. For example, consider the dire need for fast-tracking bilateral trade negotiations. Unless the foreign policy machinery emphasises the geopolitical urgency, our trade negotiators will endlessly block forward movement over less-consequential things such as Europe’s steel import quotas.

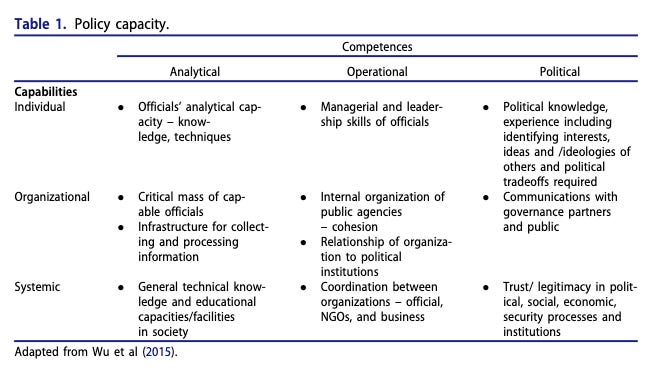

But what does a lack of foreign policy capacity mean? It is well-known that the intake into India’s foreign service is woefully short of the requirements. But there’s much more to it. In their 2019 article “India's Foreign Policy Capacity, " Kanti Bajpai and Byron Chong deploy an existing framework to assess India’s capabilities along nine dimensions.

They conclude that the capacity is weakest for Organisational capabilities, even though Indian foreign service ranks high on Individual capability parameters. On the Systemic capabilities dimension, the record is mixed. After considering alternatives, they recommend a dramatic increase in entry-level recruitment through the civil service examination.

Given the current world disorder, the government needs to focus on giving a quick boost to foreign policy capacity, or else the gaps between India’s ambitions and delivery will show up.

Two: Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology (MeitY)

Given the economy-wide impact of its decisions, MeitY is arguably the third-most important Union ministry after Finance and Defence. The ministry will make policies related to critical issues such as data protection, digital public infrastructure, semiconductors, cybersecurity, and international cooperation. Without a step jump in capacity, we can expect incompetence to show up in the policies.

Three: Economic Regulatory Bodies such as the Competition Commission of India (CCI)

I came across this piece of news earlier this week:

“Government has not accepted the parliamentary committee's recommendation to introduce the concept of "mandatory effects-based analysis" in the proposed Competition Amendment Bill.” [Business Standard, 27 Jan]

Essentially, the standing committee asked the CCI to “study the impact on consumers, innovation and competition before adjudicating a conduct as violative of the competition law”.

But the CCI refused. Like a gully cricketer who asks for underarm bowling because facing the real deal is too tough, the government argued:

“it is difficult to quantify such effects and conducting such studies may delay any corrective action. By the time we study the effects, the markets will have suffered.” [Business Standard, 27 Jan]

In other words, the CCI is admitting it lacks the capacity to govern Information Age markets. Another domain that needs a shot of state capacity urgently.

India Policy Watch #3: The Defence Budget Serves a Limited But Useful Function

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

(This is a draft of an article that was published on TheQuint website on 22nd Jan)

As soon as the Union defence budget goes live, another cycle of discussions on its size and composition will begin. Analysts will focus on how the expenditures deviate from the previous year. The government, on its part, will compare today's spending to what it was in 2014 to impress upon us that it has done enough.

Such discussions are of limited value. The budget is only a financial statement based on the government's priorities. The defence budget is then a result of intra-governmental negotiations that consider India's threat perceptions, national security goals, defence capabilities, and the economic climate. As the government doesn't release any of these upstream ideas as official public documents, the defence budget becomes a focal point for understanding India's stance.

Given this reality, the defence budget serves a limited but essential function. It needs to inspire confidence in the strategic community that India has enough fiscal power to manage the China challenge over the next few years. The fiscal reassurance is necessary because India's strategic environment is much different than in 2014. Terrorism is no longer the threat that it was back then. Pakistan, the primary strategic challenge then, has had a tough decade. International support for its military-jihadi complex has declined even as it has to contend with the Taliban on its western border and with economic mismanagement internally.

Meanwhile, Chinese actions along the border since 2017 have made it clear that India faces a wealthier and more capable primary strategic adversary over the next decade. Our defence budgets should have begun to reflect this fundamental change in the security environment. But a look at the numbers doesn't suggest so.

At the start of the decade (FY12), defence expenditure comprised 2.8 per cent of GDP and 17.6 per cent of Union government expenditure. By FY22, this has declined to 2.1 per cent of GDP and 14 per cent of Union government expenditure. In other words, defence has slipped in priority relative to non-defence functions. Moreover, the expenditure profile has skewed towards higher personnel costs, such as salaries and pensions, at the expense of an almost equivalent drop in capital outlay and stores (operational and maintenance expenditure).

The government addressed some of these issues last year. The Agnipath scheme could reduce pension expenditure, but those savings will accrue only after fifteen years. The government also increased capital outlay in the previous budget. It now makes up 29% of defence expenditure compared to 24.5% in FY20. Moreover, the navy's share in this capital expenditure has increased to 35%, up from the 27% range between FY16 and FY20. Budgetary allocations suggest that the government is trying to build up India's naval strength in response to China's challenge on the northern borders.

But these changes aren't enough. They are still incrementally positive changes. To build strength against China, the government needs to move forward on two counts.

One, we need to adopt a whole-of-government approach towards defence financing.

The defence finance crunch cannot be solved by the defence ministry alone. The solution lies in a whole-of-government approach where the government prioritises defence expenditure in line with future threat projections, even if it means reducing expenditure elsewhere. The good news is that there is enough slack in government expenditure, which, if reduced, can permit defence modernisation without affecting key developmental priorities like health, education, food and water. There are three areas where expenditure can be curtailed.

One, cut non-merit subsidies. Economists Sudipto Mundle and Satadru Sikdar find that in 2015–2016, unwarranted non-merit subsidies of the Union and all state governments combined amounted to over 5.7 per cent of GDP. The Union government doles out nearly a fourth of this. Even halving this subsidy bill can free up a fiscal space of almost 0.8 per cent of GDP.

Two, rationalise centrally sponsored and central sector schemes. Currently totalling 116, many of the Union government schemes encroach on the domain of state governments. Rationalising them will create fiscal space for defence.·

Three, sell non-strategic firms. There are currently 249 operating Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs). The Union government should divest its stake from all CPSEs except a select few of core strategic importance. It is unconscionable for the government to cut defence spending while injecting taxpayers' money into failing companies.

Two, create a non-lapsable fund for capital acquisition.

Multiple parliamentary standing committees on defence have repeatedly highlighted the need for a non-lapsable defence capital fund account as a budgetary mechanism for handling the multi-year capital acquisition processes. The Fifteenth Finance Commission also recommended the creation of such a fund. Since capital acquisition is a complex process spanning multiple years, a non-lapsable capital account would be helpful in the seamless carryover of surplus funds from one year to the next instead of the standard budgetary procedure of handing over unutilised funds back to the Consolidated Fund of India. Last year's budget didn't mention this reform, even though the union government had given an in-principle agreement way back in Feb 2021.

Money can be drawn out of this non-lapsable fund as and when a capital acquisition deal fructifies. Crucially, the defence ministry can seed such a fund using two revenue streams. One stream is monetising non-essential defence land. The defence ministry is the biggest landholder of the union government, a lot of which is now prime real estate in India's major urban centres. Selling some of this land can generate the resources to build bigger and better defence facilities away from city centres while the surplus can be parked in the capital account fund. It is immoral for the government to hold on to this land while compromising defence modernisation.

The second potential source for seeding the capital acquisition fund is to divest stakes in underperforming defence public sector enterprises. There are nine defence public sector undertakings and 39 ordnance factories under the defence ministry, operating at widely varying performance levels. Privatising some of these can help populate the capital acquisition fund.

The defence budget is another opportunity for the government to signal to its citizens and the world that it can take tough fiscal decisions in the interest of India's defence. Don't let it go to waste.

A Framework A Week: Two is Better Than One

Tools for thinking about public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

The 2x2 matrix is not exactly a public policy framework. But it is an incredibly useful tool for scenario-planning in any field or work, including public policy. These matrices are quite commonplace — you’ll find them in many consultancy reports and impact assessments.

We often think of scenarios based on the variation of a single factor, and the mental model we deploy is a linear scale. The strength of the 2x2 framework is that it helps create robust scenarios located at the intersection of two “important, independent, and uncertain” trends. The weakness of this model is that it ignores an interplay between more variables.

But how does one go about using this framework systematically? That’s where this paper, “Scenario Building: The 2x2 Matrix Technique” by Alun Rhydderch, comes in. It has a cool eightfold path to deploy this tool.

Step 1: Identify the focal issue or decision

This step involves developing a question that the scenario exercise should help answer. This is an underrated step. People often ignore this step and end up creating 2x2 scenarios that aren’t useful. An example question where scenario-planning might help: How will a US-China decoupling impact India?

Step 2: Internal Dynamics

This step involves scanning the operating environment to identify external and internal dynamics that might affect the question. In our example, some important dynamics are US-China dependence and India-China border tensions.

Step 3: Identify Driving Forces in the Environment

Here, we locate the factors that impact the internal dynamics (Step 2). For instance, some important factors that we might consider are the nature of US-China decoupling (total/selective), India’s economic dependence on the US and China, and India’s trade policy stance.

Step 4: Rank Driving Forces by Importance and Uncertainty

This step involves identifying the two most important and most uncertain drivers. In our example, the nature of US-China decoupling seems to be far more uncertain than India’s economic dependence on US and China.

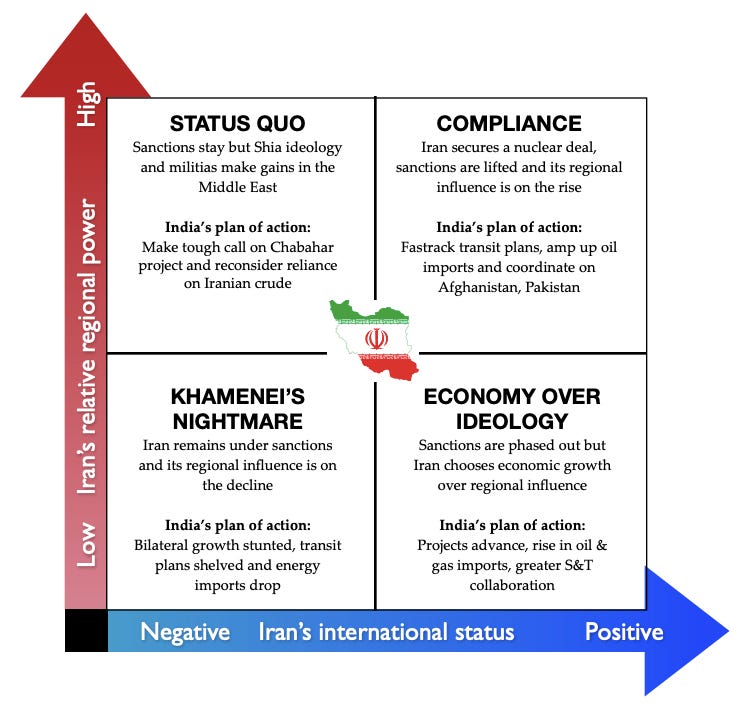

Another example is from an exercise we did at Takshashila in 2015 to answer this question: How might Iran’s global status and regional influence play out over the next decade?

Step 5: Selecting the Scenario Logic

This is a pause-and-reflect step. Here, we check if the two drivers identified in Step 4 make sense. Sometimes, these two factors might correlate, and we can populate only two scenarios along the diagonal rather than four quadrants.

Step 6: Fleshing Out the Scenarios

In this step, we project and imagine how the scenario would look like on all drivers identified in Step 3. This is a fun step and works best when done in groups.

Step 7: Implications

Each scenario would create different opportunities, threats, and possible allies.

Step 8: Selection of Leading Indicators and Signposts

In this step, we identify the indicators that can help us understand how each scenario might progress.

Check out the entire document here. It is a super useful tool.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Book] Another edition of Policy Success Case Studies is out, this time from the Nordic countries.

[Lecture] Ambassador Bilahari Kausikan’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee Memorial Lecture is gold for anyone interested in geopolitics.

[Video] A useful short explainer on the deficiencies of the Competition Commission of India.