#1: Regulation is a pedagogical fail

Instead, there are ten types of government controls

A couple of years ago, Pavan Srinath pointed me towards this excellent paper: Why public goods are a pedagogical bad. I have now come to the conclusion that the term regulation deserves the same treatment: it is a pedagogical bad, so ambiguous that it is virtually meaningless.

I say so because of two reasons.

One, the word just implies too many things. For instance, if I say that bitcoin should be regulated, this statement offers zero insight into the precise government intervention that is being referred to. It is unclear whether regulating here means banning bitcoin, imposing a price cap for trading in bitcoins, or imposing an entry license that permits this trade.

Just have a look at the list below from an excellent public policy textbook — Eugene Bardach’s A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis. The range of actions that get classified as regulation range from outright bans to merely improving complaint mechanisms. When one term can mean so many distinct things at once, it is of little help as an analytical tool.

The second reason for why regulation doesn’t make sense is because there is NO industry or sector that is completely unregulated. So, when someone says that xyz sector should be regulated, I’m at a loss because I’m pretty sure that there might be some — perhaps insufficient —regulatory intervention already in place.

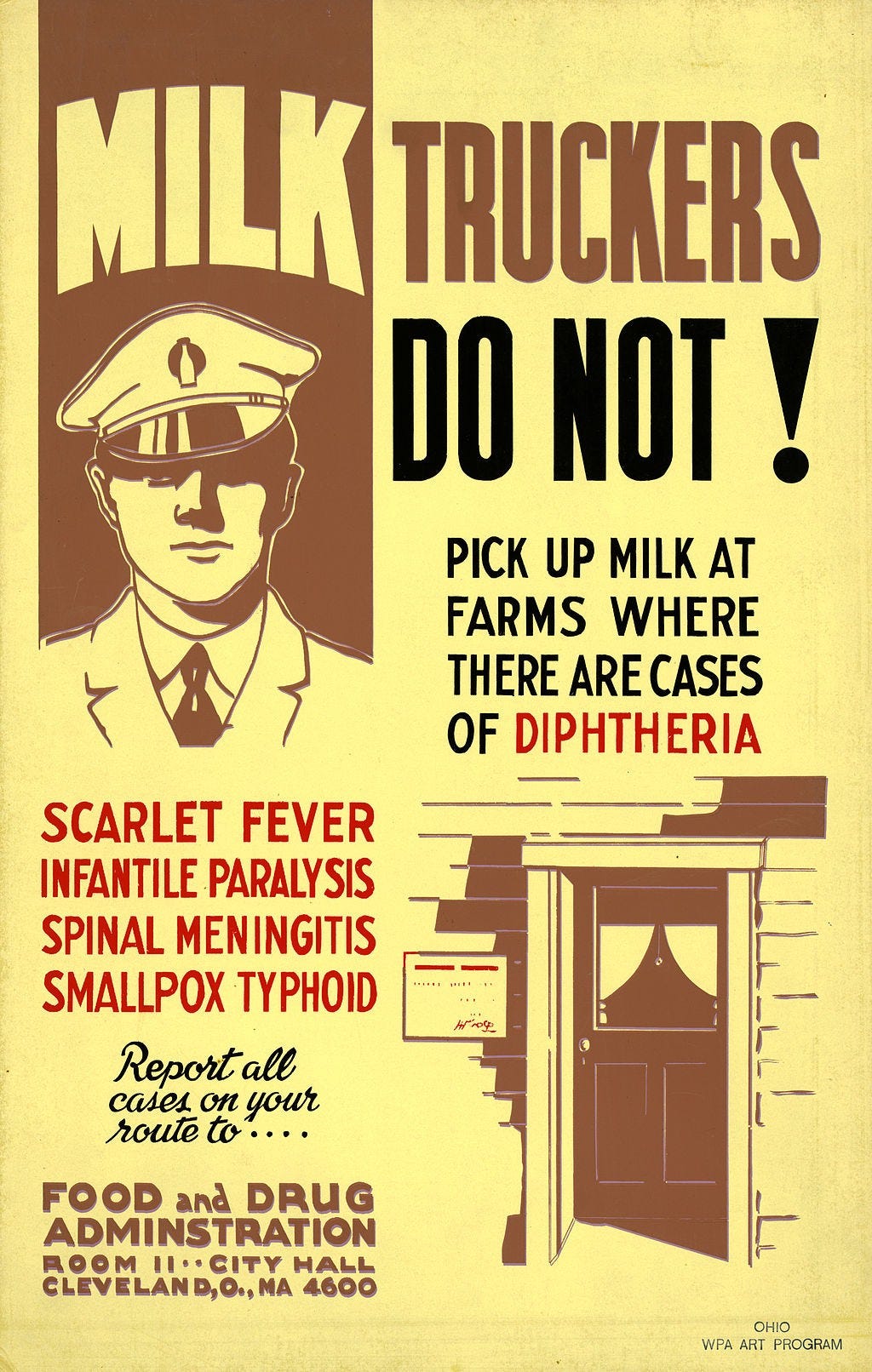

Regulation of the Milk Supply by USFDA (Source: Wikipedia)

For example, when someone talks about regulating private hospitals, it does not mean that the hospitals are unregulated today. There are many entry and exit criteria that these hospitals are already adhering to: from the space required for each ward bed to the minimum number of human resources, there are an extensive set of ‘regulations’ that are already in place (see the Clinical Establishments Act Standards from 2010).

If regulation is a pedagogical fail, what are the alternatives?

Instead of using the leaky umbrella term regulation, Anupam Manur and I were able to break the term down into the following categories. This is perhaps not an exhaustive list. All suggestions for improvement are welcome.

No further regulatory intervention required. The government can choose to ignore calls for tightening control. For example, a government may choose to ignore calls for caps on private school fees.

Output quantity controls. An extreme form of this intervention is a ban on the production of a good. A common form of this intervention is to allow production of a good or service but to restrict the quantity that can be produced. For example, industrial licenses in the pre-1991 era had restrictions that prevented companies from producing beyond a license capacity threshold.

Output type/quality controls. Mandating the disclosure of information is a common way of controlling the type and quality of controls. By making tax filing and audits compulsory, or by making it necessary for food marketing companies to disclose nutrient information on their products, the government controls the type and quality of outputs required. Setting pollution emission standards is also, in effect, an output quality control measure.

Output recipient controls. Governments can also restrict where the outputs go. Export restrictions fall under this category of regulation. So do priority sector lending mandates for banks.

Input quantity controls. For example, the Indian government specifies a reserve requirement for banks in the form of gold, government-approved securities before providing credit to the customers (referred to as the Statutory Liquidity Ratio).

Input type/quality controls. Reservations in jobs are an example of controlling the type of input. Worker safety regulations translate into specific inputs such as requiring the presence of a doctor on-site in a workplace.

Input provider controls. Through import restrictions, for example, governments prevent inputs from outside the country. Another example is a regulation that prevents monopoly formation by mandating that the supply-chain of a company cannot be owned by the same company.

Imposing output price controls. Price ceilings and price floors are commonly used regulations and constitute a separate category.

Entry controls. Governments can specify the conditions that need to be met even before firms can start production. For example, it is mandatory that a hospital cannot begin operations without a registered medical practitioner on its payroll. Another example: governments prescribe a lower limit for the capital required before an individual can launch a bank.

Exit controls. Governments can specify the conditions that need to be met before firms can stop production. For example, bankruptcy laws specify what firms need to do before closing down operations entirely.

Most importantly, each of these controls has different intended and unintended consequences. And ‘regulation’ conflates all of them.

So, the next time someone says that xyz sector of the economy should be regulated, ask them to explain which of the ten controls are they referring to? What will be the unintended consequences of that measure? And, are those risks worth taking up?