This newsletter is really a public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PS: If you enjoy listening instead of reading, we have this edition available as an audio narration on all podcasting platforms courtesy the good folks at Ad-Auris. If you have any feedback, please send it to us.

- Pranay Kotasthane & RSJ

It’s the 72nd Republic Day today (as we write this). The Constitution of India is a revolutionary document. The past few years have seen some wonderful works of scholarship about our constitution. We’d like to call out a few here.

The Constitution will remain a distant and daunting document as long as we don’t develop a habit of referencing it directly. Thankfully, EBC has been publishing a coat pocketbook version since 2009. It works great as a reference book. And it doesn’t hurt that it looks elegant and makes for a wonderful gift. As an aside, a dream project of mine is to convert the constitution into a knowledge graph that visually connects the cross-referencing articles in the Constitution. If any AtU reader has the technical chops to make this happen, please ping us.

Madhav Khosla’s India’s Founding Moment: The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracyis a brilliant and erudite work that is essential to understand the radical nature of our Constitution and the interplay of ideas and debates among people who cared deeply for this nation that led to its creation.

Rohit De’s A People’s Constitution: The Everyday Life of Law in the Indian Republic challenges the idea that our Constitution was the product of an elitist imagination whose impact in the lives of ordinary Indians was minimal. De uses four examples to make his case about the Constitution empowering the people of India to take on the state.

Tripurdaman Singh’s Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment of Constitution of India shows how the idealism of the Constitution became a difficult burden to bear while running a government. No constitution can be eternally infallible. But we set a precedent of changing the architecture of our Constitution really early in the life of our Republic. We might never recover from that ‘original sin’.

Gautam Bhatia’s The Transformative Constitution: A Radical Biography in Nine Actsexplains in detail why the Constitution at its core aims to bring about a social revolution. Many a constitution aim to transform the polity and economy but few aim to change society itself. This is what sets the Indian Constitution apart. The classic work on this line of reasoning is Granville Austin’s The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation.

This passage from Rohit De’s A People’s Constitution helps make sense of the remarkable achievement that the Indian Constitution is.

“The Indian Constitution was written over a period of four years by the Constituent Assembly. Dominated by the Congress Party, India’s leading nationalist political organization, the assembly sought to include a wide range of political opinions and represented diversity by sex, religion, caste, and tribe. This achievement is striking compared to other states that were decolonized. Indians wrote the Indian Constitution, unlike the people of most former British colonies, like Kenya, Malaysia, Ghana, and Sri Lanka, whose constitutions were written by British officials at Whitehall. Indian leaders were also able to agree upon a constitution, unlike Israeli and Pakistani leaders, both of whom elected constituent assemblies at a similar time but were unable to reach agreement on a document. The Indian Constitution is the longest surviving constitution in the post-colonial world, and it continues to dominate public life in India. Despite this, its endurance has received little attention from scholars. [Rohit De, A People’s Constitution, pg 2]

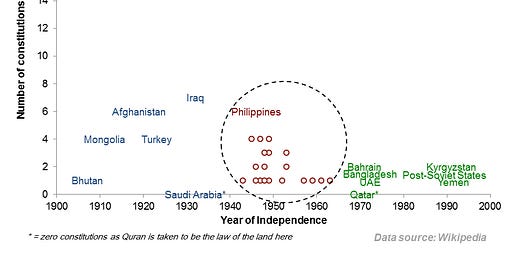

To explain the last point visually here’s a comparative chart plotting the number of constitutions against the year of independence for Asian states.

India, of course, falls in the heavily clustered zone labelled “independence era states” - political communities that overthrew European colonialism to establish new nation-states. Zooming in this era, we find that a handful of constitutions in Asia have survived. Only three amongst them had a constituent assembly that brought together people to make their own constitutions. And even amongst the ones where one constitution has survived this far, most have been beset by politically active militaries and dictatorships. The Indian constitution is without a doubt an exception to be proud of.

Among the many flaws that are often pointed out about our Constitution, the one we disagree most with is about how unmoored it was from India’s past. The accusation is we didn’t try and locate the great ideas and values of the Constitution in our past. This created a sense of distance of the ordinary Indian from the ideals of the people’s Constitution. We have two problems with this line of argument. First, this alienation from our tradition (if true) was to be bridged by later scholars and interpreters of the Constitution including legislators and administrators. The members of the Constituent Assembly shouldn’t have been expected to also write a commentary on it in parallel. Second, there are multiple references to how the principles enshrined in it are consistent with the best of our historical tradition.

Another common criticism is that the Constitution reproduced two-thirds of the GoI Act of 1935 and hence wasn’t transformative enough. What’s forgotten of course is that the 1935 Act itself was a result of a powerful Indian independence movement’s consistent political pressure on the British government. The charge of not being transformative enough” needs rethinking.

We will leave you with two excerpts of speeches made in the Assembly that support the assertion that the Constitution is consistent with the best of the Indian historical traditions while leaving out the undesirable elements.

On 17th October 1949, J.B. Kripalani made both the points we have stated above:

“Sir, I want, at this solemn hour to remind the House that what we have stated in this Preamble are not legal and political principles only. They are also great moral and spiritual principles and if I may say so, they are mystic principles. In fact these were not first legal and constitutional principles, but they were really spiritual and moral principles. If we look at history, we shall find that because the lawyers and politician made their principles into legal and constitutional form that their life and vitality was lost and is being lost even today.

Take democracy. What is it? It implies the equality of man, it implies fraternity. Above all it implies the great principle of non-violence. How can there be democracy where there is violence? Even the ordinary definition of democracy is that instead of breaking heads, we count heads. This non-violence then there is at the root of democracy. And I submit that the principle of non-violence, is a moral principle. It is a spiritual principle. It is a mystic principle. It is a principle which says that life is one, that you cannot divide it, that it is the same life pulsating through us all.

As the Bible puts it, "we are one of another," or as Vendanta puts it, that all this is One. If we want to use democracy as only a legal, constitutional and formal device, I submit, we shall fail. As we have put democracy at the basis of your Constitution, I wish Sir, that the whole country should understand the moral, the spiritual and the mystic implication of the word "democracy". If we have not done that, we shall fail as they have failed in other countries. Democracy will be made into autocracy and it will be made into imperialism, and it will be made into fascism. But as a moral principle, it must be lived in life. If it is not lived in life, and the whole of it in all its departments, it becomes only a formal and a legal principal. We have got to see that we live this democracy in our life.”

And more famously, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar in his last speech at the Constituent Assembly draws upon our past:

“It is not that India did not know what Democracy is. There was a time when India was studded with republics, and even where there were monarchies, they were either elected or limited. They were never absolute. It is not that India did not know Parliaments or Parliamentary Procedure. A study of the Buddhist Bhikshu Sanghas discloses that not only there were Parliaments-for the Sanghas were nothing but Parliaments – but the Sanghas knew and observed all the rules of Parliamentary Procedure known to modern times. They had rules regarding seating arrangements, rules regarding Motions, Resolutions, Quorum, Whip, Counting of Votes, Voting by Ballot, Censure Motion, Regularization, Res Judicata, etc.

Although these rules of Parliamentary Procedure were applied by the Buddha to the meetings of the Sang has, he must have borrowed them from the rules of the Political Assemblies functioning in the country in his time.This democratic system India lost. Will she lose it a second time? I do not know. But-it is quite possible in a country like India – where democracy from its long disuse must be regarded as something quite new – there is danger of democracy giving place to dictatorship. It is quite possible for this newborn democracy to retain its form but give place to dictatorship in fact. If there is a landslide, the danger of the second possibility of becoming actuality is much greater.”

The above lines are followed by his famous ‘Grammar of Anarchy’ passage. He knew what he was talking about.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Video] Ambedkar’s speech at the Constituent Assembly

[Document] Judgment on Shankari Prasad vs Union of India: The First Constitution Amendment Act, 1951 was challenged in the Shankari Prasad vs. Union of India case. The Supreme Court held that the Parliament, under Article 368, has the power to amend any part of the constitution including fundamental rights.

[Podcast] On Puliyabaazi, Rohit De joins Saurabh and Pranay to discuss India’s tryst with constitutionalism.

[Article] Democracy and the Republic - the differences between these two concepts.

Share this post