This newsletter is really a public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PS: If you enjoy listening instead of reading, we have this edition available as an audio narration on all podcasting platforms courtesy the good folks at Ad-Auris. If you have any feedback, please send it to us.

Global Policy Watch: Capital Markets (Enter, Stage Right) - Radically Networked Societies

- RSJ

It is difficult to write a newsletter this weekend and not talk about GameStop. Even for a public policy newsletter. But I like to believe if you hold your gaze long enough at any news going around, you will find a public policy problem. This becomes especially true if you run a twice-a-week public policy newsletter. Everything starts looking like a public policy issue soon enough.

Anyway, a lot of what’s happened with the GameStop stock over the last couple of weeks is part of the broader gusts of change that’s buffeting society and culture since the global financial crisis (GFC). In that sense, it is useful to try and look beyond the story to understand the GameStop phenomenon. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let’s do a quick recap of the story.

GameStop is a brick-and-mortar video game seller. A fairly routine presence across large malls across America, GameStop was meandering its way into irrelevance over the last many years. After all, who goes to the mall to buy video games anymore? And then the pandemic arrived to compound its woes. Its days seem numbered. Soon it would join the likes of Blockbuster, JC Penney and scores of other businesses that couldn’t reinvent themselves for the digital age. That was the consensus on Wall Street.

The Short Squeeze

But the Street is a strange place. A business with no prospects is also an opportunity to make money. By shorting its stock. You borrow a few shares of the company from someone (usually a broker) and you sell them in the market. Since you are borrowing the shares you pay a small charge for it. Plus the broker wants a bit of insurance in case things go bad. So you keep some money in an account that the lender can access in case things go south. Since you believe the stock price will go down, you wait for it to happen. When it does, you buy the same number of shares at the lower price and return them back to the broker. You pocket the difference. This is how it goes for any ordinary investor. If you happen to be a star fund manager of a hedge fund, you make it known to the world you are shorting the stock. You have a platform to voice your views and you send out a signal the stock will tank. Often this turns out to be a self-fulfilling prophesy. The stock does go down on your word and momentum does the rest. You make a tidy profit for your clients and a fat commission for yourself.

Of course, plans go awry too. The stock goes up contrary to your bet. You think this is temporary so you wait. But the broker is nervous and wants some assurance. So you top up the account where you had put some money in case things went bad. If the stock keeps rising, you have to keep topping this up. Since your loss can be unlimited (the stock can keep rising), you feel hemmed in as the stock rises. You feel squeezed. So you decide you want to call this bet off. The only way to do this is to buy the stock at an elevated price. You do that. But remember you are not the only one who had shorted this stock. As the likes of you buy the stock at the elevated price, the price goes up further. And other short sellers feel the squeeze. This is called short squeeze. It can wipe you out.

That’s that. Life is too short to know any more about short selling.

And The Gamma Squeeze

On the other hand, there are people who bet the stock price will go up. That’s usual. The riskier bet is buying a call option on a stock. Here you don’t buy the stock. Instead, you buy an option that the stock will go above a certain price. This is a small bet. You lose all money if the stock doesn’t reach there. But if it does, you make a lot of money on a small bet. Since this is a bet, there’s always the other party (market maker) that’s sold you the bet. They sell many such bets. And to hedge their bets they go out and buy a small number of the underlying stock. In case the stock price does go above the bet price, they will atleast recover some of their losses if they own that stock. For simplicity let’s call the rate of buying the stock to hedge the bet as ‘delta’. You can see where this is heading. If the stock keeps going up and more people buy call options, you will have the market makers buy more of that stock. This in turn drives the price further up. That is the delta keeps becoming faster. This rate of change of delta is called gamma. It is like acceleration. And this kind of squeeze in favour of stock going up is called the gamma squeeze.

Life is complicated enough already to know any more about Greek letters in stock markets.

Unstoppable GameStop

Events conspired in mysterious ways to bring both the short squeeze and the gamma squeeze to the GameStop stock overt the past few weeks.

There’s a Reddit forum (r/WallStreetBets) that has a mix of investors - small-time investors with deep knowledge of the markets (very few), bored young men (mostly men) who trade in markets for a lark (few more), thrill-seekers and degenerates who trade by turning economic logic on its head (many more) and gullible new investors who are drawn into this in the hope of getting tips to make a quick buck (the largest number). The forum members see themselves as Davids taking on the Wall Street establishment (Goliath). Fun fact: only 14 per cent of Americans directly invest in individual stocks and 3 out of 4 of them belong to the top 20 per cent of American households by income. Calling themselves the ‘little guys’ is a bit rich.

Sometime last summer a few members of the forum started making a case for GameStop as a stock that’s undervalued. The stock was trading at about $4 then. There was no rationale. It was pure optimism backed by hopes of a turnaround in the business. But that’s how even the best equity analysts often make a case for a stock. Or a VC fund values a start-up. The stock caught fancy of a few members in the forum and rallied a bit.

In September, Ryan Cohen, an entrepreneur who sold his online pet store Chewey for $3.5 Bn a few years back, bought about 12 per cent of GameStop at $8.4 per share. Cohen believed he could turn GameStop into an online success. This was the validation the WallStreetBets members were looking for. The stock doubled in three months soon after.

In January this year, things got weirder. GameStop was one of the most shorted stocks in the market (the total shorts were more than the available outstanding shares). As it rallied up, some of the prominent short sellers started talking down the stock. Particularly, two firms - Melvin Capital and Citron Research - called out the insanity around the stock. Now a word about short sellers, hedge funds and other established fund houses on Wall Street. For years since the GFC, there’s been a wave of simmering anger against them from the retail investors. Deservedly. These firms have done it all - cartelisation, manipulation of stocks leading to fake momentum and selling toxic products to ordinary investors. The calling out of GameStop rally by them triggered something extraordinary.

The WallStreetBets forum decided to apply the short squeeze on the short-sellers. It was the mother of all squeezes. Meanwhile, GameStop brought Cohen and his two buddies on to their Board. Momentum was on. Gamma squeeze was in. The stock went berserk. From $20 to $320 over two weeks with wild fluctuations. Over 20 Bn shares were being traded daily making it the most traded stock in the world. Nothing had changed in its underlying business. In fact, the numbers were looking worse. But this wasn’t about GameStop anymore.

In these two weeks, the whole thing has turned into a movement. It is no longer about making money. It is about making a statement. Socking it in the face of the establishment. There’s no logic anymore. It is a cult. Citron and Melvin have closed their positions and made extraordinary losses. These wins have given more life to the movement. Shorted stocks of companies that can hardly have a future have quadrupled. These include names like AMC, Blackberry (remember) and Nokia. The whole thing is nuts.

The bar for absurdity in Wall Street lore is high. Short squeezes have a long history. The original baron, Cornelius Vanderbilt, once short squeezed the life out of NYC Council members who were betting against him. The railroad empire he built was the result of that. George Soros took a $10 Bn short position on the British Pound and almost broke the Bank of England in 1992. And in the early days of the pandemic last year, the crude oil price went below zero. There’s something about the GameStop story that tops them all. There was a rational economic explanation to the earlier events however bizarre they appeared. This one goes beyond economics.

Markets In The Crosshairs

Four trends now deeply embedded in our culture and politics seem to have marked their arrival in the markets with this story.

Radically Networked Societies (RNS) meet Capital Markets: Nitin Pai and Pranay define a radically networked society as a web of hyper-connected individuals, possessing an identity (imagined or real), and motivated by a common immediate cause. The emergence of RNS aided by cellphones, cheap data connectivity and social media platforms is a phenomenon for the hierarchical state to contend. The immediate cause that motivates an RNS could be irrational but before the state or the established institutions can even put their shoes on, the RNS might have gone around the world twice with their message. This is what fuelled the bizarre stories emerging from the suicide of a Bollywood star during the pandemic or with the rise of the QAnon movement in America. Well, RNS is now in the markets. The WallStreetBets is a classic case of RNS. A bunch of hyperconnected, mostly anonymous investors who view themselves as Wall Street outsiders and whose immediate cause is to take down short sellers and hedge fund managers. That their chosen targets are a greedy, egoistic bunch divorced from reality has made their job easier. The story sells itself - the long due revenge of the ordinary investor.

Knocking the experts off their pedestal: The experts are all sold out. They have an agenda and they won’t tell you the truth. That’s the message that’s mainstream now in politics and culture. This is what drives the anti-vaxxers, climate science deniers, trade protectionists and other conspiracy theories going around. Now add the Wall Street experts to this list. If a research analyst says a stock has no future, bet against her. Do the irrational thing and if it pays off for even a day, you have been proved right.

The crowd is right: What are people like you buying, watching, eating or wearing? So many people can’t be wrong. If I can watch and enjoy something based on what others are watching, I can buy a stock the same way. Zero brokerage platforms like Robinhood and Public have built their business models around this. Gamify the stock markets. Make it addictive. The millennials seeking thrill sitting at home during the pandemic have a new destination. Buy stocks, buy options and have fun. Let them buy high, sell low and take a selfie while doing so. You earn street cred doing this within your community. Who cares about the losses? YOLO.

It is personal: Hyper-personalisation, the market of one, call it by any name. You are now invested deeply in your belief and your platform. It is your identity. The echo chamber you inhabit keeps reinforcing this belief. After a while, even the platform has no control over you as Twitter and Facebook have seen over the years. And Robinhood discovered to its dismay last week. They will take you down too. Because it is all personal. You can’t just let Citron Research or Melvin Capital have a view about GameStop that’s contrary to yours. They have to be taken down.

The GameStop phenomenon is just the beginning. It is like the Arab Spring of 2011 engineered on Twitter. Today it seems like a moment when the little guys took on the big, brutish establishment and won. This victory, like that of the Arab Spring, will be pyrrhic. The genie that escaped from that movement has been hard to put back into the bottle. The markets will now have to contend with the genie. It is out.

For those like us who battle to protect the fast receding middle ground everywhere, this is a new front. Anything that elicits support from both Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ted Cruz must give the classical liberal a pause. That moment for Capital Markets is here.

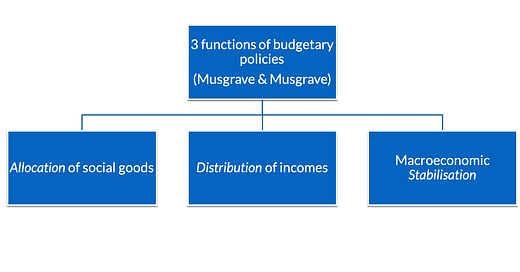

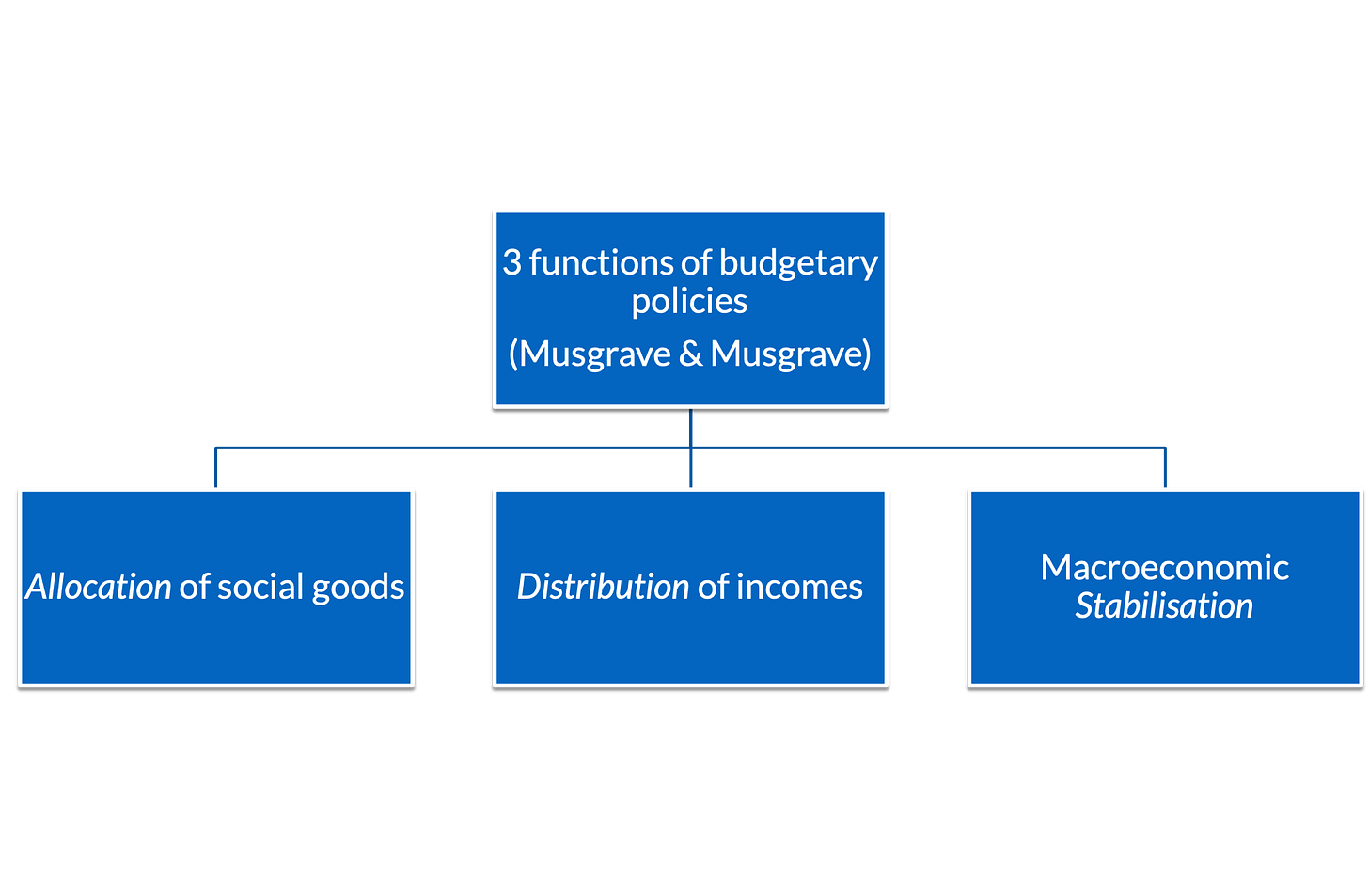

A Framework a Week: Three Functions of the State

Tools for thinking public policy

- Pranay Kotasthane

Public Finance in Theory and Practice (1973) by Musgrave and Musgrave has an elegant classification of budgetary functions. Since you’ll be bombarded with the news about the union budget over the next few days, this classification would be of some use.

From a public finance perspective, the three main functions of the State are allocation, distribution, and stabilisation.

Allocation of social goods needs to be done primarily by the State because the market is likely to under provide such goods. Consider a private company willing to install street lights in your area for a fee that will be collected from all residents. Residents are likely to underpay because the benefits of good lighting will accrue to strangers beside themselves. Most people would prefer freeriding, the result being unlit streets. Here’s where the state comes in to allocate such social goods and imposing mandatory taxation, it tries to prevent freeriding.

Distribution of income or wealth is another important and perhaps the most controversial function of the State. If the income distribution is not in line with what the society perceives as being “fair”, the State tries to alter the distribution pattern. For example, it is now widely accepted that poverty and food insecurity are undesirable in the Indian society and hence there is broad support across the political spectrum for some subsidies to the poor.

Further, there are three fiscal instruments for redistribution:

a tax-transfer scheme, combining progressive taxation of high-income with a subsidy to low-income households. example: tax money used for a direct benefit transfer for low-income families.

progressive taxes used to finance public services, especially those such as public housing, which particularly benefit low-income households.

a combination of taxes on goods purchased largely by high-income consumers with subsidies to other goods which are used chiefly by low-income consumers. example: GST rate of zero for grains and salt but tenwty-eight percent for cars.

All three instruments of distribution distort markets and hence need to be used in moderation. In a previous edition, we have written why a tax-transfer scheme is better than loading a tax-system with multiple objectives.

Finally, macroeconomic stabilisation seeks to achieve desirable levels of macroeconomic indicators such as inflation and unemployment since the market-determined values might not be optimal. Increase in the budget for the employment guarantee scheme (MGNREGS) due to COVID-19 is an example of budgetary policy being used to stabilise the unemployment situation.

Stabilisation can happen through these two instruments:

Monetary instruments such as interest rates, discount rates, and open market operations, or

Fiscal instruments such as raising public expenditures on infrastructure.

Often, a budgetary policy designed for one of these functions can cause problems in the other. For example, a government trying to stabilise inflation by banning exports of commodities can affect the distribution of incomes of producers. This is the precise predicament of export bans on onions. Hence the grand challenge is to design policies that minimise such conflicts.

Humour: Green shoots

The Union budget will be presented tomorrow and we bet you’ll hear the phrase ‘economy green shoots’ at least once. Many growth rate-based narratives around the economic recovery will compete with each other. So, here’s a pic in anticipation of all that — green shoots on a money plant.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Audio] Amit Varma with Pranay on Radically Networked Societies in The Seen And The Unseen

[Article] Kevin Roose’s The Shift column in The New York Times: The GameStop Reckoning Was a Long Time Coming

[Article] Sarthak and Pranay have an article in Deccan Herald on an underrated budget document.

Share this post