While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways.

Audio narration by Ad-Auris.

PolicyWTF: Our Democracy In Wave 2

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

- RSJ

It is difficult to write anything with clarity when almost every second message you read is a cry for Oxygen, ICU beds, Remdesivir or plasma. This isn’t an exaggeration. This is the reality of every urban Indian today. Yet they are lucky. The ability to amplify is itself a privilege. There are many others going silently into the night; mourned by their voiceless kin but unnoticed, uncounted and unmourned by the state. Because it is inconvenient to even acknowledge them.

This is a difficult moment for India. It is not easy to write with perspective and acuity about our criminal neglect of lives while retaining empathy for those on the frontlines of this battle. So, excuse me if I ramble a bit in this edition.

No Information, No Democracy

There’s a lot made about democracy in India. If we were to believe our own hype that is. We have a rambunctious multi-party system. Our elections are festivals celebrating people’s choices. The janata is the janardhan, apparently. For years, the more cynical among us have seen through this charade. Today, the despairing shallowness of these claims are laid bare for all us to see.

At its heart, democracy is about availability of information. As information became more accessible and moved with greater speed in the industrial age, societies had to adopt democratic norms. Other choices could only be coercive. Because information is power. It helps you compare, to make informed choices and to hold those in power accountable. It is no surprise then among the first thing any authoritarian regime does is to control information. Information makes democracy tick. Without it, democracy is just a periodic voting exercise.

The remarkable thing about India’s pandemic response is the sheer absence of information available to the public. Even the Supreme Court cannot get direct answers out of the government. The number of vaccines we have purchased in advance, the current stockpile we have, the monthly rollout plan we have in mind or the price of the vaccines. Nothing is known. The anticipated number of infections we might have for every district in the country, the future need for Oxygen, ventilators, doctors, healthcare workers or technicians in each district, the real mortality rates, the data on genome testing, the amount of foreign aid or where it is going - the list is endless. There are no past datasets, there’s barely any data being collated now and there’s no forecast for us to plan a better response future even as we see the pandemic spreading to rural areas in India. We don’t have a daily dashboard or targets against which we monitor our response to a virus that’s knocked us over. Administrative incompetence and deliberate official suppression have brought us to this parched information landscape.

This lack of information in the midst of a catastrophe renders democracy void. Only a chimera remains. Every living moment is filled with anxiety because you are a step away from being drawn into the Covid apocalypse. You cannot plan even for the week ahead. You cannot judge the actions of the government because there’s hardly any information. You read a news report about foreign aid gathering dust at the airports and the next day the partisans of the government point to another report on how things are moving quickly. In this see-saw battle between information and disinformation, in the midst of this epistemological fog, we have to find the right direction.

Democracy is about choice in the hands of people. Choices are made by weighing the arguments put up by either side. Arguments need information. Cut the information supply and democracy gasps for breath. It is not just patients that are running out of Oxygen in today’s India.

There Won’t Be Any Reckoning

This also makes the next point that I want to discuss almost irrelevant. Is the handling of the second wave a moment of reckoning for PM Modi and his government? In any normal, functional democracy with rational voters and a modicum of opposition, it should have been. But I’m not sure about it happening in India.

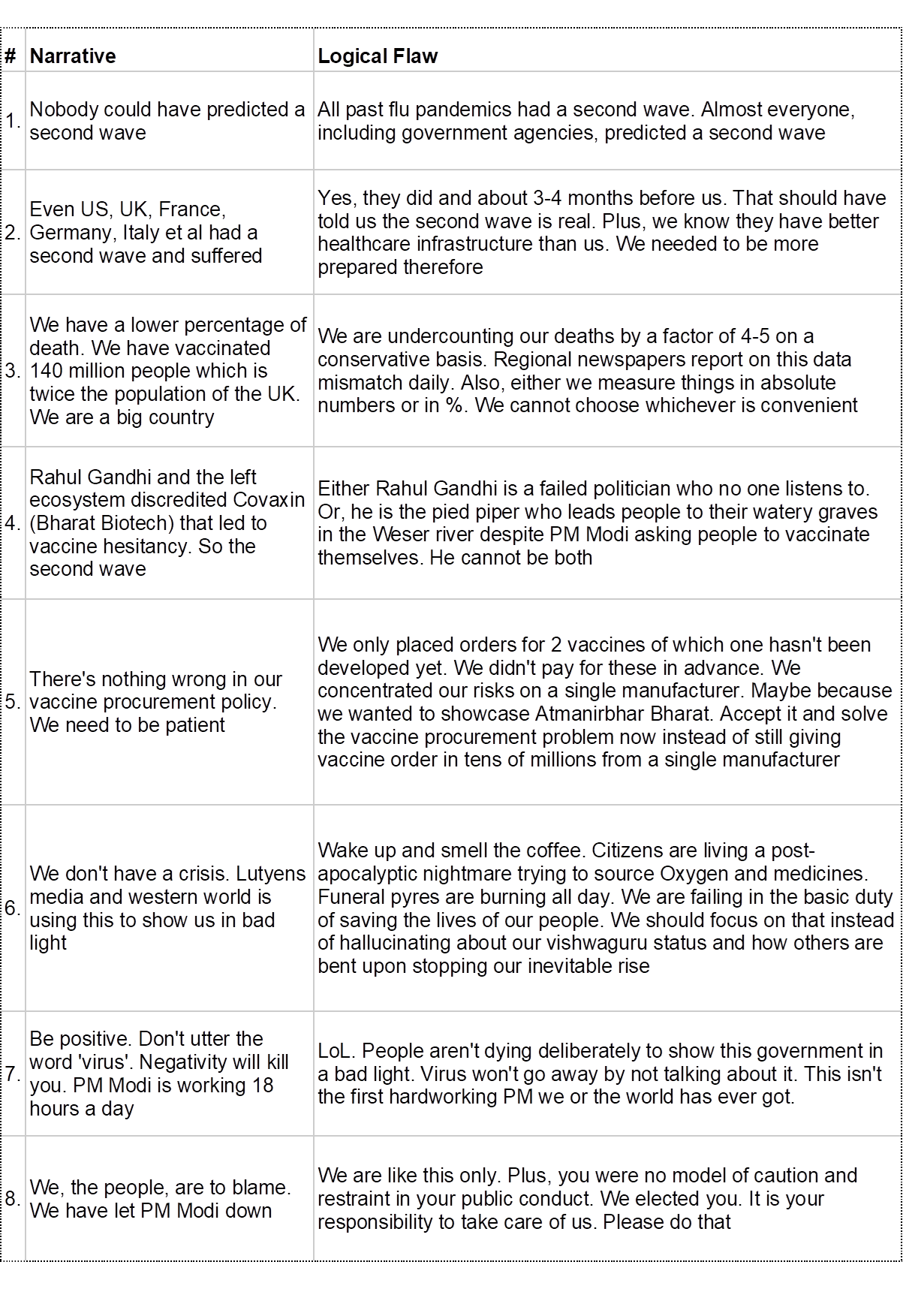

First, the lack of transparency or information makes it easy for the government to spin narratives that take away the heat from it. We have already seen some remarkable feats of narrative building in the past month. Merely listing them down inspires awe within me in for the narrative entrepreneurs building them. But it also boggles my mind on how these logically weak or inconsistent narratives aren’t countered with vigour. I have made a simple table below to reflect this.

Any reasonable person with an open mind will come to a similar conclusion as I have reached in the table above. But people lose their sense of perspective while thinking about politics.

This is an old problem. Why do people find it so difficult to let go of their political beliefs?

I don’t want to go into either the philosophy or the neuroscience of this issue in this edition. Some day I will. The short answer is this. People who have agency (in India those that are educated, employed and with means) have a disproportionate belief in the soundness of their judgment. They consider they have arrived at their political beliefs using reason and on their conviction of what’s wrong with the world. This process is deeply personal. It becomes a part of their identity. This causes them to invest emotionally into any politician or a political party that furthers this view. This is different from familial or religious ties that are accidents of birth. This is a product of your own logical mind. A mind that, all things considered, is superior to others. This is the reason why families or old friendships cleave on political beliefs. Even blood is thinner than political faith because the political is personal and vice versa.

In India of today, there is a large coalition of people who have invested deeply in PM Modi and his vision of India. This coalition is useful to study to understand why there won’t be a reckoning despite the abject failure of this government to provide the basic right of life to its citizens.

First, there are those in the coalition who believe we wasted the first 67 years of our independence pursuing wrong economic and social policies. Merit was stymied, enterprise was killed and a rigid bureaucracy along with a venal state held us back. Among this lot, there are those who are disappointed already with PM Modi today and sit on the fence. The other side of the fence doesn’t make for great company either. The great hope there is in the form of Mamata Banerjee whose only virtue is that she defeated the BJP. Governance isn’t exactly her forte. This is the kind of political thinking that’s got us here. Anyway, the greater number in this section of the coalition are the ones who respond to the ‘system’ is all flawed message. So, PM Modi needs more time to smash this ‘system’ to smithereens. He is forever the outsider for them.

Then we have the garden variety bigots of various hues who believe India is held back because the minorities in tandem with global forces are undermining it. They hark back to India’s glorious past and its abiding civilisational values. These are the consumers and distributors of the millions of fake messages churned out by the WhatsApp factories. The general consensus here is a thousand years of ‘foreign’ rule set a superior but somewhat naïve race back. Our path to salvation lies in showing these ‘foreigners’ their place while going back to those civilisational values. In PM Modi they find a man who will set us on the path to deliverance.

And the final section includes those who have a nuanced view that our civilisational values can be blended with modernity to arrive at a modern conception of Indian state that’s different from the Nehruvian one. Indeed, I think this can be a worthwhile project. But it needs a philosophical and cultural articulation of our values that is in sync with the current reality of a diverse India and a modern world. And it has to be compelling enough to rewrite the constitution in a way that won’t fracture society. To draw an analogy, it needs clear thinking of the likes of Paine, Burke or Montesquieu with the civilisational understanding of Vivekananda or Aurobindo. That’s a tall order. Instead they have the likes of Sadhguru and Rajiv Malhotra to aid their efforts. In any case, in PM Modi, they have the anti-Nehru at the helm. And that’s good enough for now.

The despair about the future of India that’s often written by a section of commentariat these days might be overblown. We have lived through terrible political and economic choices for many centuries. We will survive. Not thrive. And that’s tough to swallow. We had a window of opportunity to realise our potential as a nation and to improve the lives of our people. We could have been a contender. It is all in the past now.

But to most Indians today it doesn’t matter. A tendentious reading of the past and a majoritarian fantasy of the future has clouded our judgment. Form takes precedence over substance. Appearances matter more than truth.

No surprise then to discover the final counter to any political argument in India today is - aayega to Modi hi.

India Policy Watch: What Matters and What Doesn’t

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

The Union government has received a lot of flak over its criminal negligence in managing the pandemic response. It deserves nearly all of it, and more. We have written about this over several editions.

Today however, I want to look at three incorrect — or at least problematic — frames being used to blame the government’s pandemic response, shoddy as it is. The intention is to ask the right questions. Only then can we hope for the right answers.

Incorrect Frame #1: Blame Vaccine Diplomacy

As the cases have skyrocketed and vaccine supplies have plummeted, India’s vaccine diplomacy has come under the scanner once again. The question doing the rounds is that did India commit a grave mistake in gifting vaccines to other nation-states? With the benefit of hindsight, the dominant narrative today is yes, by prioritising vaccine exports over domestic inoculation, India did a disservice to its own people.

I disagree.

In edition #102, I made a realist case for India’s vaccine diplomacy. I stand by that view. The original sin of the Union government, of course, was that it didn’t place enough vaccine orders and hasn’t done so even until now.

Rewind to February and you’ll notice how complacent the government was of having conquered the virus had peaked. It seemed that the government would sail through a dying pandemic with a snail paced vaccination campaign. It is with this line of thinking that vaccine diplomacy began.

Another way of thinking about vaccine diplomacy is to think of its opportunity cost. At the current vaccination rate, India would’ve had five additional days of supplies had it not given any of the nearly 10.7 million doses as gifts to other countries. In fact, a majority of the deliveries (nearly 35 million) have been under commercial terms between manufacturers and other countries. It’s likely that countries would’ve not helped India in the current crisis the way they did had India blocked exports of vaccines earlier.

Holding the Union government accountable for its mistakes is important. Equally important is identifying what the exact mistake was. By internalising that India was wrong in extending its help to other countries in its own time of help, we would be learning the wrong lesson. Such heuristics tend to stick around for long in the Indian strategic affairs community. Try arguing for developing overseas operations military capability of any kind and the idea will be shot down citing the IPFK failure in Sri Lanka more than three decades ago. It’s important that vaccine diplomacy isn’t perceived as another IPKF moment. This pandemic is as much about learning the right lessons as it is about not learning the wrong ones.

Incorrect Frame #2: “ದುಡ್ಡಿಲ್ಲ” Government Has No Money

Nero fiddled while Rome burned. How we love this story. Every ineffectual leader in the times of crises gets equated to Nero. This time around, the charge of callousness rests on the government’s plan of redeveloping India’s central administrative area at a reported cost of nearly ₹20,000 crores. The critiques argue: can’t the government redirect some of this money for increasing the number of hospital beds, oxygen plants, and vaccine procurements? — problems that are dire and important today.

From a political perspective, this line of attack probably makes for a powerful narrative. I wouldn’t know. But wearing a policy analyst’s hat, this logic makes little sense. That’s because the government has enough monetary resources at its command for fighting the pandemic and building a new parliament, both.

Facts of the matter first. The ₹20,000 crores amount is to be spent over multiple years, of which less than ₹2,000 crores is being spent this financial year. For perspective, this is 0.05% of the Union government’s FY21-22 budget.

Moreover, such arguments asking for diverting money from one purpose to another play in the hands of the government by inadvertently giving it safe passage as long as it can show monetary constraints. The truth of course is that the Union government has enough options at hand to beg, borrow, and steal money for fighting the pandemic.

The State as an institution is unparalleled. It doesn’t easily run out of money like households do. If it does, it always has the option of monetising deficit (albeit at the risk of future inflation). And if there ever was a case to be made for monetising deficit, a raging pandemic would definitely make the cut. After all, what is the use of a democratic republican State that cannot spend to protect the life of its citizens dying by the thousands every day?

In fact, after a lot of hullabaloo about how asking the states to procure vaccines from manufacturers might lead them to fiscal troubles, most states, — including low-income ones such as Bihar and Odisha — have promised free vaccines to all adults in the 18-45 age group. As an example, we estimated that Karnataka would require approximately ₹3900 crores to vaccinate all its residents in the 18-45 age group for free. Of which, ₹3176 crores can be borrowed immediately by using RBI’s Way and Means Advance facility.

Don’t listen to government excuses over money in these times.

PS: As far as the Central Vista Redevelopment Project is concerned, India would indeed need a new parliament a few years down the line once the delimitation of constituencies takes place in accordance with the 2031 census (thanks to a helpful reader, Kamil, for dispelling my belief that delimitation would happen in 2026). This is not a new demand and India is capable enough of funding the redevelopment of a small pocket in Delhi even as it fights a pandemic.

PPS: It beats me why the government could not postpone the Central Vista Redevelopment Project until the second wave peaked. That would’ve been prudent.

Incorrect Frame #3: The Liberalised and Accelerated Phase 3 Strategy is to be blamed

The move to allow state governments, private hospitals, and industrial establishments to procure vaccine doses directly from the manufacturers has been under fire ever since it was announced. The criticism is on two counts.

One, this approach would lead to confrontation between state governments seeking better deals from manufacturers. Two, the Union government can use its scale to strike better deals with both domestic and foreign manufacturers.

The solution suggested is that the Union government must incentivise vaccine production, procure all these vaccines from manufacturers, distribute them using a transparent formula to the states, and provide all vaccines for free. Moreover, do all this in mission mode.

The problem with this criticism is that it heavily overestimates the Union government’s capacity. To expect a government that couldn’t strike advance contracts with a handful of manufacturers to do all the above is to ignore the constraint that inadequate state capacity imposes.

From a citizen’s perspective, to expect a different result while repeating the same failed strategy doesn’t make sense. I suppose most people think that the real cause of the government’s ineffectiveness is either the lack of money, intent or both. In reality, the problem is a deeper one, of capacity — bureaucratic, intellectual, and implementation.

Another deeply ingrained narrative today is that if Indian governments can organise Kumbh Mela (spot the irony) and nationwide elections, it should also be able to organise a mission mode vaccination campaign. Unfortunately, it is more likely that vaccinations will continue in the slow burn mode over multiple years and will need to deftly change track as the virus mutates and better vaccine variants get discovered. I doubt a centrally planned system will be able to solve for all this.

State capacity should change public policy alternatives we choose and hence, it’s better to get state governments and private players to get involved. As the number of vaccine candidates increases, more options will become available to these entities, far quicker than a centrally planned system run by a low-capacity union government.

As Ajay Shah and Amrita Agarwal write:

“These changes will unlock the energy from varied Indian buyers — states, firms, communities, and individuals — and increase their accessibility to global supply.

Indian buyers need to explore the global vaccine market and be comfortable paying market prices. As an example, the Israeli government paid $28 per dose (i.e. ~2,000 per dose) to Pfizer and Moderna in late 2020, which was 43 per cent higher than the price paid by the US and the EU. This got them rapid vaccine deliveries. They have vaccinated most of their population and now do not force people to wear masks.

If Indian persons (private and public) put down ~2 trillion, i.e. a billion doses at ~2,000 per dose, this would yield transformative impact. This is a price worth paying to control the economic and human cost.”

Of course, this doesn’t mean the Union government can wash its hands off entirely. It still has an indispensable role to play. One, only it can accelerate domestic production by getting all vaccine manufacturers to share knowhow and ramp up capacity. Two, while the global supply squeeze eases, it must create a transparent prioritisation mechanism for distributing the scarce supply within states.

In sum, to get the right answers, we need to ask the right questions, again and again.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Pratap Bhanu Mehta writing for the Indian Express: “If our politics continues as usual over the next few months, the devastation to our lives will be immeasurable.”

[Report] Samanth Subramanian asks Why is India, the world’s largest vaccine producer, running short of vaccines?

Share this post