Global Policy Watch: Ud Jayega Bezos Akela*

Bringing an Indian perspective to burning global issues

- RSJ

Homo sapiens first went to space in 1961.

60 years later, a new species, decidedly less superior than Homo sapiens, has succeeded in going to space.

Billionaires.

Remarkable. So, what should we make of it?

A Race To Nowhere

There are three arguments against the space race among billionaires. And these arguments play into the wider debate about capitalism and inequality that’s roiling the developed world. I will take a stab at rearticulating them.

To start with we have the old charge against capitalism of being self-obsessed, indifferent and out of touch with the reality of the world around them. In a time when a global pandemic has destroyed lives and livelihoods and the poor still don’t have access to vaccines, the spectacle of billionaires spending hundreds of millions on their toys isn’t appetising. Our moral intuition says it is wrong. Surely, it is their wealth and they have the freedom to pursue whatever they fancy. But that wealth could have more productive uses that make the world better. And it isn’t just a prayer to the goodness within the hearts of the billionaires that we need. There’s a right that the society has over some of that wealth they have accrued through dodging taxes (or at least not paying their fair share), keeping employee wages low and using sharp elbow tactics to monopolise the markets. Taking off into space during these times is like showing a giant middle finger to the rest of humanity.

The second argument offered against the space fantasies of billionaires is that it will amount to nothing. The science of sending a shuttle to orbit the earth and come back is more than 60 years old. So, no new ground in science is being broken here. Also, any talk of space travel or living on Mars underestimates the difficulty of a person being in space for any amount of time. Sim Kern has a good piece on this in the Salon:

“Around half a dozen astronauts live up there (International Space Station) at any given time, bouncing around a narrow tube with roommates they didn't choose and who can't properly bathe for months on end. The wifi is slow. The food is not Michelin starred, to say the least. Their sleeping situation is akin to a floating coffin. And pooping involves a complicated procedure in a port-o-potty where the door is a plastic curtain and everything floats.

Astronauts' time is micromanaged by a team of experts on the ground. Unlike future space-tourists' imagined itineraries, much of their time is spent working on actual science, but a great deal is dedicated to mere survival as well. Space-dwellers must exercise at least two hours a day to keep their bones from turning to goo. They spend a ton of time studying systems and conducting repairs on equipment that frequently breaks because space wants to kill you.”

That’s just orbiting the Earth. She also dashes any pipe dreams about colonising Mars:

“And what about Musk's dream of a colony on Mars, or at least the Moon? Those are astronomically less feasible. The farther away from Earth you're trying to sustain life in space, the harder it gets. And while they have the benefit of gravity, the surface of the Moon and Mars are covered with a powdery regolith that gums up mechanisms.

….So despite Musk's lofty claims of making humanity "a multi-planetary species," that's way, way beyond the realm of current technical possibility. And his claim is especially absurd, considering that in order to generate the wealth that sustains billionaires like Musk, we're rapidly destroying the one planet we can live on — Earth.”

No matter how tough things get at Earth, it will still be infinitely more livable than Mars for a long, long time. It might be better to spend money to continue keeping Earth viable than to plan a human settlement on Mars.

The whole thing does sound like a billionaire pissing contest.

The third argument made is about how all great scientific and technological advancement is funded by the government using public money and then exploited for private benefits by venture funds, family offices and shrewd entrepreneurs. All in the name of enterprise and capitalism. This is another case where the heavy lifting is done by the state taxing everyone while the benefits are concentrated among the very few. Anand Giridharadas in his newsletter The Ink has a sarcastic take on this:

“I have an idea for a reality show. It’s called “Billionaires Solve Problems the Government Solved a Long Time Ago and Then Explain How Much More Efficient They Are Than Government.” I may ask Richard Branson to produce.

In the pilot episode, Elon Musk will “invent” something he calls the Digital Method of Verification. He will pioneer a whole system whereby people can take a driving test and receive a plastic card that I’m told Musk will refer to as a “license” and thus gain permission to drive on public roads.

In the second episode, Jeff Bezos will “innovate” a new kind of bookstore that buys books but then gives them out to people for free, so long as those books are returned. He will fund it with some of the money he doesn’t pay in taxes. He will call it the Lending Interesting Books to Raise Aspirations for Reading Youths, or LIBRARY, program.”

.. you get the drift.

Good In Theory, Bad in Practice

I have limited sympathy for these arguments, compelling and strong on rhetoric though they may be. I will add here I find nothing heroic about Branson or Bezos going to space. It may not be as inane as them buying a yacht or a mansion. But it is close. My differences are on the principles used to criticise them.

Let me start with the criticism about the timing of these missions. Is there any reason to believe had these space flights happened a year down the line, we wouldn’t have seen a similar criticism? The world is an unequal place as it has been for most of human history. There’s data to show it has become less unequal in the past two centuries. There’s a problem of judging any spending by billionaires by what else it could have achieved for society. Because why should this moral matrix stop at the billionaire?

Surely someone spending money on an icecream could have used that money to buy food for the hungry. I could go on. Stretched to its absurd logic this argument would mean we should stop every ‘unnecessary’ spend till we have redistributed wealth to the extent that everyone in the world has food. But it won’t stop there. Because human wants increase. Once everyone has food, there will be some who will desire a house (or, maybe an iPhone?). And the same cycle of redistribution will start till everyone has a house or a phone.

You can see where this is going.

Any patterned distribution programme will never stop till everyone gets exactly what the other has. And that can never be achieved naturally. It will need state coercion. This is the lesson learnt from 20th-century history. Worse, like I have written in previous editions, anytime we arrive at the final equilibrium of a patterned distribution programme, the next transaction shatters it. This is natural. Human beings are all different and unique. They will have different time preferences (current vs future), risk appetites and utility functions for every transaction. To preserve some kind of fragile, equally distributed pattern in society will require every transaction to be approved by a central authority lest the pattern fails. This is the Hayekian road to serfdom. We must stay away from it.

I also have a minor issue with the argument Kern makes that this doesn’t really take science further. To many of us, science seems to work in episodes of breakthrough advances. The reality is otherwise. There’s a gradual build-up of knowledge that leads to bigger questions and more fundamental inquiries. This is what’s needed in space science. Private space exploration has been real for the past two decades. There are networks of private satellites that track weather patterns, pollution, green cover depletion, nuclear proliferation in rogue states and help in navigation. Others are trying to provide broadband access to millions whom local telecom companies cannot serve.

Manned space exploration hasn’t been a huge priority for national space programmes for a long time. Governments don’t have the capital and the end of the cold war reduced any further incentive for it. The billionaires might be in a pissing contest right now but there is a frontier here. And it needs to be explored. If private capital is happy doing it, we shouldn’t complain. There might be future entrepreneurs out there who might benefit from this democratisation of space. We might not yet know in which way. But the beauty of science is things don’t change in a linear fashion. The human capacity to challenge a new frontier and go beyond what’s imaginable is the basis for our civilisation.

Lastly, I come to the sarcastic piece by Anand Giridharadas about billionaires only discovering now what the government has already done many years back. This is perhaps the most illogical of the arguments. But it appears to have a strong currency among the woke left. Let me make three counterarguments.

One, barring the period between the end of WW2 and the early 80s, there isn’t a great state-sponsored track record of supporting innovation anywhere, anytime in history. And let’s be clear that the period of exception wasn’t because the state loved science and technology. It was the cold war that was driving its investment. The central idea, to put it simply, was to annihilate the human race. So to look back at that period with some sense of pride about the achievements of the state is delusional. We had pursued science for wrong ends and handed enormous powers to a few who controlled these weapons of mass destruction. That we didn’t end the world in that period is providence. God knows we tried. The billionaires today can use their enormous wealth and science in many ways detrimental to our race. That they don’t isn’t providence. They are interested in other things than modelling themselves on villains from the Bond franchise.

Two, there is a market failure in basic science and research. Research has positive externalities and the likelihood of any kind of commercial success is low. There is a reason why it has to be supported through state funds, grants and philanthropy as it has happened over the ages. Beyond that, there’s enterprise and risk capital that’s needed to transform basic research into commercially viable products. These aren’t mutually exclusive. There’s no disconnect here. To keep harping on how all the basic research for, say, an mRNA Covid vaccine was done using government grant misses this point. Reading Walter Isaacson’s The Code Breaker you realise how important a patent is for those in basic science. There is love for science, for sure. But claiming intellectual property for future gains is as critical. And the road from a scientific breakthrough to a commercially viable product is arduous. Entrepreneurs aren’t just picking up ideas from the lab for free and turning into billionaires.

Three, if state sponsorship, and not entrepreneurial flair (or greed), was the only thing needed for scientific innovation and commercial success, we should have seen tremendous breakthroughs coming from the erstwhile USSR, India, Cuba and Venezuela. But you know the score there. One of the features of the youth today is how much of history seems to be lost on them. The way the discourse is going we might just reinvent the French and the Russian revolutions all over. And pay for all the benefits and the consequences. There’s an air of inevitability to this happening. This was what Nietzsche probably meant when he spoke of eternal recurrence in human affairs. We are doomed to it.

I will end this piece with the one argument I agree with against billionaires in space. There’s one use of the money spent that’s better than trying to make Mars livable. It is to continue making Earth more livable. It is the best home we can ever have.

Hannah Arendt in her 1958 classic, The Human Condition, starts her prologue with the deep desire that humans have to escape the world the way it is to a world that we can create from scratch. Arendt starts off by describing the launch of the Sputnik, the first-ever satellite launched into space by us. She writes:

The immediate reaction, expressed on the spur of the moment, was relief about the first “step toward escape from men’s imprisonment to the earth”.

… Should the emancipation and secularisation of the modern age, which began with a turning away, not necessarily from God, but from a god who was the Father of men in heaven, end with an even more fateful repudiation of an Earth who was the Mother of all living creatures under the sky?”

And her conclusion on this is what I can get behind:

The earth is the very quintessence of the human condition, and earthly nature, for all we know, maybe unique in the universe in providing human beings with a habitat in which they can move and breathe without effort and without artifice.

.. For some time now, a great many scientific endeavours have been directed towards making life also “artificial”, toward cutting the last tie through which even man belongs among the children of nature. It is the same desire to escape from imprisonment to the earth that is manifest in the attempt to create life in the test tube, in the desire to mix “frozen germ plasm from people of demonstrated ability under the microscope to produce superior human beings” and to “alter their size, shape and function”; and the wish to escape human condition, I suspect, also underlies the hope to extend man’s life-span far beyond the hundred-year limit.

* Kumar Gandharv singing Kabir on the futility of it all

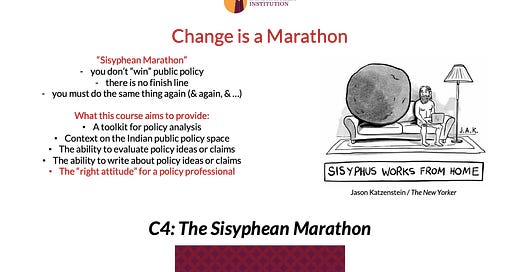

If the content in this newsletter interests you, consider taking up the Takshashila GCPP. The certificate course is customised for working professionals. Intake for the 30th cohort ends on 22nd August.

This slide from the Fundamentals of Public Policy module, co-anchored by Pranay Kotasthane and Ameya Naik gives a good idea of what the course has to offer.

PolicyWTF: Clipping our Wings

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Pranay Kotasthane

Have you tried booking domestic flights recently? If yes, the unreasonably high prices would have made you pause. It’s likely that you would’ve shrugged it off by blaming the government for raising taxes on fuel, and shelled out the money anyway. Well, you are partly correct. Indeed a government policyWTF underlies the high ticket prices but it’s not the one you think.

I realised the reason while trying to book a flight ticket myself. I noticed a strange coincidence — not only were the prices high, but all airlines were also charging the exact same high price. A representative price chart is given below.

Turns out, a few restrictions that the Ministry of Civil Aviation had imposed last year during the first wave, are still in place. And that explains this weird price chart.

Specifically, the government has restricted airlines in not one but three different ways.

One, it put a cap on the total capacity that airlines can deploy. Note, this doesn’t mean a restriction on the number of passengers in a flight but a restriction in terms of the total number of flights that an airline can operate. Two, it also put a ceiling on the ticket price depending on the sector and travel time. And three, it put a floor on the ticket price meaning that tickets couldn’t be sold below a particular price even if the airlines wished to do so.

The stated intent for each of these measures was equally baffling. The capacity restriction is apparently to discourage discretionary travel, the price cap is to protect the consumer, and the price floor is to protect the financially weaker airlines.

Let’s give this bizarre policy the Anticipating the Unintended treatment (edition #48). One of the most commonly observed effects of government intervention is that rent-seekers often distort government policies to serve their own interests. And that’s what seems to be the real reason behind these three-fold restrictions. The capacity restrictions and price floors appear to be a clientelistic policy to clip the wings of the largest player in the market.

The end-loser in this game is the consumer — ticket prices of most airlines have conveniently settled to just below the price ceiling regardless of how early you book your tickets.

Given the other challenges that less-fortunate Indians are facing today, this issue might seem trivial. Think again. These government interventions have created precedence for the government to intervene in the interests of “financially weaker” players, even if it comes at the expense of the consumer. This is what should worry us. The fact that these restrictions are in place sixteen months after the pandemic began indicates that the rent-seekers are already in the driving seat. Today, the government wants to protect weaker airlines; tomorrow it might extend its “protection” to other sectors, further harming consumers.

Finally, the government’s primary responsibility should be to ensure that aeroplanes and airports don’t cause further spread of the virus. Mandating COVID-19 detection tests or fully vaccinated certificates might directly address this risk. Price bands and capacity caps serve no such purpose. The government should back off.

#TWIL: A Boston Tea Party Myth

This section looks at something new and striking we learnt over the week

— Pranay Kotasthane

It’s my ignorance that until this week I thought the Boston Tea Party protest was caused due to high taxes. Turns out, it was actually caused due to a tax cut!

This is what I read in the book Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue by two leading authorities on taxation, Joel Slemrod and Michael Keen.

The reason is a bit convoluted. It involves India, smugglers, and of course, the East India Company. Here’s the story as I understand it.

Starting in 1768, there was a nominal tax on imports (including tea) landing at American colonies. This tax was a statement of British suzerainty over the colonies rather than a means of revenue collection. Given the weak enforcement, almost 60 per cent of tea was smuggled, escaping this nominal tax levy. The tea itself was procured by the East India Company from China and auctioned in Britain, from where it found its way through legal and illegal means to the colonies. Apart from the import duty applied on reaching the colonies, a similar charge was applicable when the tea first landed in Britain. So far so good. The East India Company was raking in the profits while the colonies’ smugglers had their own party going on in parallel.

Then came the Bengal Famine of 1769 which devastated the company-controlled revenue areas. Despite ample intimidation and coercion, the Company’s revenue collection wouldn’t improve. Given the importance of the Company to the British Empire, other ways had to be found to revive its fortunes.

Someone found a novel way out — reduce the costs of the Company’s tea trade with the colonies. The British government refused to reduce the import levy on goods entering the colonies as it could be perceived as giving up a sovereign right over the colonies. Instead, the import levy on tea reaching Britain was refunded to the Company.

Regardless, the net result was that the tea reaching the colonies became cheaper, threatening the fledgling smuggling business. With their margins undercut, they sought to contest this tax cut. These smugglers went on to play a major role in the protests that dumped chests of tea from vessels carrying the ‘tax-cut’ tea at Boston.

Quite fascinating.

As the authors remind in the book, taxes are seldom the first reason behind independence movements. But they often end up becoming the last straw, the immediate cause that sparks world-changing protest movements.

A Framework a Week: Describing a State’s Policy on a Geopolitical Issue

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

How do we explain India’s position on the Israel-Palestine Issue? How to evaluate China’s actions in Afghanistan? These kinds of descriptive questions are quite common in geopolitical analysis. In order to structure the thinking about such questions, here’s a simple three-point framework.

To evaluate a State A's policy on X issue:

Ask what are A's interests in X issue? Identify strengths, weaknesses, risks and opportunities. To avoid a superficial rational-actor model analysis, also consider the stances of a few important interest groups within A.

List the actions A has taken on X issue thus far.

Ask how actions listed in #2 affect the interests outlined in #1? Have some actions exposed some weaknesses even as they opened up new opportunities? Have there been fallouts, unintended consequences?

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Video] Intelligence Squared Debate: “Should Billionaires Be Abolished?” For the motion: Linsey McGoey, Professor of Sociology and director of the Centre for Economic Sociology and Innovation at the University of Essex. Against the motion: Ryan Bourne, R. Evan Scharf Chair for the Public Understanding of Economics at Cato Institute

[Audio] Economist and Nobel Laureate James Heckman of the University of Chicago talks about inequality and economic mobility with EconTalk host Russ Roberts.

[Book] The Power to Tax: Analytical Foundations of a Fiscal Constitution is a classic work in Public Finance by Geoffrey Brennan and James M Buchanan.

Share this post