#17 Finance Commission Is Not Family-planning Commission

Indian troops in Afghanistan, 15th FC, internal migration, and what's really really tough for governments to do

This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PolicyWTF: Finance Commission Is Not Family-planning Commission

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

Nitin Pai’s 2014 post The real problem is not overpopulation but under-governance punctures one of the most longstanding causal narratives about India’s stymied-progress story.

Nevertheless, the overpopulation narrative remains a powerful intuition which has been internalised even by several government institutions of repute. The 15th Finance Commission, for example, decided that a 12.5% weightage be given to demographic performance (measured as the inverse of fertility rate) while deciding the share of devolved funds across states. This was reportedly done to assuage the demands of the ‘well-performing’ states which opposed using 2011 population as one of the criteria for tax devolution on the grounds that it punishes states which have been better at managing their populations. The 15th FC report has this to say:

Better performance in reduction of TFR also serves as an indirect indicator for better outcomes in health (especially maternal and child health) as well as education. Hence, this criterion also rewards States with better outcomes in those important sectors of human capital. Since this is an important performance criterion to reward efforts made by States in controlling their population and achieving better human capital outcomes in education and health, we have decided to assign a total weight of 12.5 per cent.

The Malthusian line of thinking survives: population is the problem.

My argument is that if the objective of general-purpose transfers is to enable comparable levels of public services at comparable tax rates, it is only fair that the latest population data be used as is. Justifying the use of ‘demographic performance’ assumes that general-purpose transfers are levers for family planning. They aren’t. Family planning and population control are better managed through interventions on the expenditure side of budgets. And that is happening organically across India — just that the starting points are different for different states.

In fact, the Finance Commission should have used population projections for the period 2020-2025 in order to decide on the demands for the same period. This way, it would have rewarded states which have been migrant magnets instead of punishing states which have higher absolute fertility rates.

For more on this topic, Anupam and I recorded an All Things Policy conversation:

A Framework a Week: What’s Easy & What’s Not?

Tools for thinking public policy

In the last edition, I spoke about three ways to classify government interventions. Assuming you have these tools at hand and you plan to attack your favourite policy problem, which of these tools would you choose? Perhaps the most important factor before diving in is to assess if the state capacity required for that particular intervention exists, can be built up, or is out of reach. In that sense, it is useful to know things that can be done easily and the ones that can’t, especially when there is dearth of state capacity. Those who can’t perform addition will not be able to compute square-roots either.

Kelkar & Shah, in their book In Service of the Republic, build on a landmark paper by Pritchett & Woolcock (referenced in the HomeWork section) to identify what’s tough and what’s easy for a government to do. These are:

Transaction-intensity: it is easier to build state capacity where the number of transactions is low. For example, it is easier for the government to do curriculum design (few transactions) than get classroom teaching right (crores of transactions everyday).

Discretion-intensity: it is easier to build state capacity in areas where low discretion is needed. For example, taking in deposits is easier for a bank to do but approving loans to small businesses is tough because the latter involves higher levels of discretion.

Stake-piling: when there is more at stake for private persons, they will try to influence the outcomes in their favour, making it tough to achieve state capacity. For example, the job of SEBI is a high-stake game where a few highly-knowledgeable investors might be trying to rig the game in their favour.

Secrecy levels: it is harder to achieve state capacity in areas closed to open feedback and criticism. For example, the space programme’s successes and failures cannot be hidden while those of the defence production programme are often hidden. The former is where India does relatively well in.

This is a powerful insight to assess the complexity of governmental actions. Before deciding on a government intervention, assess where that action lies on these four criteria.

The authors further argue that better IT systems can reduce discretion in the hands of a government functionary (assuming that is desirable), thereby reducing some of the complexity.

It will be a good exercise to identify government actions in your area of concern (health, education, fiscal policy etc.) and map these on the four-point scale of complexity. My guess is that often times our governments jump into ‘computing square-roots’ without even being able to ‘add two integers’.

Matsyanyaaya: Should India Send Troops to Afghanistan?

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

This debate has risen from the ashes, once again. A rather-convincing rationale in favour has being that an Indian military involvement in Afghanistan will shift the battleground away from Kashmir and make the Pakistani military-jihadi complex divert its resources towards the Durand Line. However, this argument has not been able to find much traction in the past and number of strategic, logistical, and historical reasons have been put forward over the years in opposition to this bold idea.

Should India think differently this time around? We have an article coming up which argues that bolstering anti-insurgency institutions should take primacy over economic development projects from the Indian side, which does not necessarily require the presence of a large number of Indian troops in Afghanistan.

Regardless of the imminent US withdrawal, India’s interests in Afghanistan haven’t changed. India hopes to build up Afghanistan’s state capacity so that Pakistan’s desires of extending control can be thwarted. Given this core interest in a changed political situation, what’s needed in the long-term in the security domain is to build the strength of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF). Without a strong ANDSF — which comprises the army, police, air force, and special security forces — peace and stability in Afghanistan will remain elusive. India’s aim should be to help the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan claim monopoly over the legitimate use of physical force.

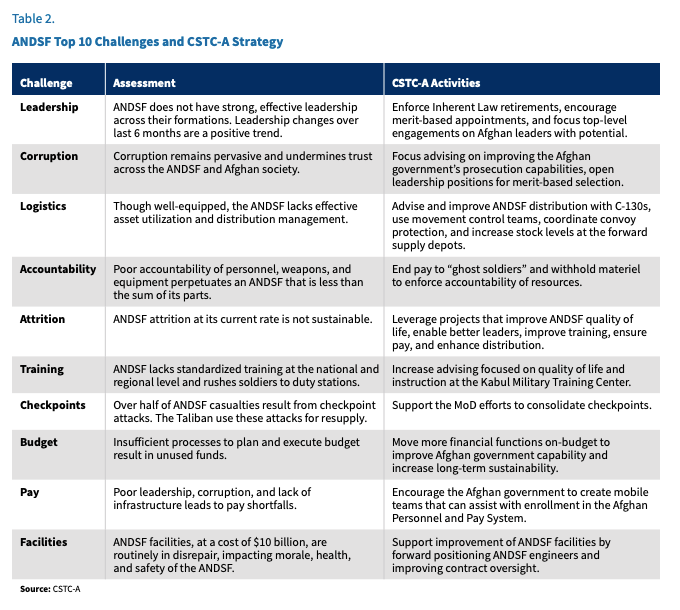

Any analysis looking at India’s military options in Afghanistan should thus start with an identification of the challenges faced by the ANDSF and how India can pitch in to meet those challenges. A study conducted last year by the Combined Services Transition Command-Afghanistan (CSTC-A) — a US-led multinational organisation charged with the planning, programming, and implementing reform of the ANDSF — identified ten challenges being faced by ANDSF.

Counterintuitively, this study brings out the fact that the biggest challenges faced by the ANDSF are related to the decline in the quality of human resources at hand rather than the shortage of financial resources. This is where India can come in. Indian expertise could prove useful in tackling each of the ten challenges identified above. Sending Indian forces might help resist the Taliban in the short-term but that’s not going to enhance the strength of the ANDSF along the dimensions mentioned above.

India Policy Watch: Internal Migration is Having a Bad Time

Insights on burning policy issues in India

I had a tweet thread on internal migration arguing that in no case should free movement of Indians within India be trampled upon under the garb of local culture, overpopulation etc. — it still remains the route to prosperity.

This comes in the context of the ongoing debate on the Citizenship Amendment Act which is focused on international migration. However, I find both sides conveniently forget how Indian states are unquestioningly and steadily raising entry barriers for fellow Indians.

The case in point being how easily Andhra Pradesh got away with its 75% reservation policy in the private sector for locals. Here’s the complete thread:

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] An eightfold path for beating a populist by Larry Diamond is pretty interesting. This framework also shines some light on why the Delhi elections produced the results that they did.

[Paper] ‘Solutions When the Solution is the Problem: Arraying the Disarray in Development’ by Pritchett & Woolcock is a must-read paper for development scholars and practitioners.

[Paper] Narrative Economics by Robert Shiller, which embraces the importance of stories for improving the economics discipline.

[Podcast] The Science of Economics - Ajay Shah and Pavan Srinath discuss the problem with economics academia and methods. It is a must-listen conversation for public policy enthusiasts.

[Book] Sixteen Stormy Days: The Story of the First Amendment to the Constitution of India. If you can get past the relentless tirade against Nehru, Tripurdaman Singh’s narration of the first amendment saga is quite engaging.

That’s all for the week. If you like this newsletter, please do read and share.