India Policy Watch: Why is UBI Back Again?

Insights on burning policy issues in India

- Pranay Kotasthane

The Universal Basic Income (UBI) proposal made it to last week's policy headlines. The occasion was the release of a report commissioned by the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister. Written by the Institute for Competitiveness, the State of Inequality in India Report bats for “raising minimum income and introducing universal basic income” to reduce “the income gap and equal distribution of earnings in the labour market”.

There is no cost-benefit analysis or implementation details of the UBI in the report. Nevertheless, since this report has been commissioned by a government advisory body just a couple of years ahead of the next national election, the report has rekindled the conversation on UBI.

What Do We Know About the UBI in India?

UBI has been extensively discussed ever since the Economic Survey 2016-17. It is one of those rare ideas for which you will find liberal and progressive arguments both for and against it. So I’ll skip the usual arguments and get to the crux of the UBI in India.

What we know is that a “Universal. Basic. Income.” is an impossible trinity in the Indian context. The government can at best meet two but not all three of its elements—a basic income that won’t be universal; a universal income that will be way below what qualifies as “basic”; or something that is universal and basic but not in the form of an income.

This trilemma arises due to two reasons. One, India is just not rich enough for the government to fund a full UBI by taxing citizens at reasonable rates. The Economic Survey estimated that even a non-universal basic income for 75% of Indians would cost nearly 5% of the GDP. For context, the total expenditure incurred by the union government including all its portfolios was approximately 13% of GDP before the pandemic.

Two, some proponents of UBI argue that the government can stop existing implicit and explicit subsidies, and use the savings to fund a UBI. The UBI would eliminate leakages, obviate the need for complex delivery machinery, and reduce incentives for corruption, they explain. But in a democratic setup where every political party finds it imperative to give individual handouts before elections, this is a leap of faith. It’s more likely that taxpayers will foot the bill for all current subsidies in addition to the UBI.

Realising this trilemma, political proposals after the Economic Survey report have tended towards the first option— a targeted basic income scheme, which is non-universal by definition. One such formulation, the Minimum Income Guarantee Scheme for the Poor (MIGS), made it to the Indian National Congress’ 2019 manifesto.

What Explains the UBI’s Return to the Headlines?

This conversation on variants of UBI has picked up the pace again. Like any major crisis, the pandemic has impacted the poor more than the rich. And hence, various income support schemes are back in favour. The Overton Window seems to be shifting. Interestingly, this trajectory towards increased monetary transfers after a major crisis was anticipated in a book nearly 60 years ago.

In a 1961 book titled The Growth of Public Expenditure in the United Kingdom, economists Alan Peacock and Jack Wiseman observed the patterns of government spending in the UK between 1890-1955. The dominant view at that time was that government spending as a proportion of the overall economy keeps rising organically as citizen demands grow with rising incomes. In a poor country, most citizens make do with the State providing them with the bare basic public services. But as incomes and government revenues rise, citizens demand that the State also provide them with quality education, low-cost healthcare, and affordable housing, and so on.

Peacock and Wiseman challenged this view of the organic growth of government spending. They saw that government spending rise in the UK happened in the form of step-jumps due to major crises (and there were many in their study period).

Their explanation of this phenomenon was as follows. In normal times, the level of public spending is capped by the acceptable level of taxation. Even if citizens might find a higher level of government spending desirable, they won’t accept a higher rate of taxation in return. This equilibrium is shattered by a crisis such as a war, where government spending and rates of taxes increase to manage the immediate difficult situation at hand. However, once the crisis recedes, new ideas of tolerable taxation levels emerge, and government spending does not go back to its original position. This conjecture came to be known as the Peacock-Wiseman Hypothesis (PWH).

Are we seeing PWH in action in India, because of COVID-19? If one were to look at costly expenditure policies such as UBI, speculations about a GST rate of 8% replacing the 5% rate, and the high fuel taxes, it does seem that we are moving towards a new normal in government spending.

Another interesting element of this hypothesis is the “inspection” effect:

“social upheavals impose new and continuing obligations on governments both as the aftermath of functions assumed in wartime (e.g., payments of war pensions, debt interest, reparation payments) and as the result of changes in social ideas. Wars often force the attention of governments and peoples to problems of which they were formerly less conscious—there is an "inspection effect," which should not be underestimated.”

The optimist would say that the inspection effect might lead Indian governments to finally focus on key areas such as pro-market reforms, liberalisation of factor markets, defence, poverty reduction and public health.

But the realist would argue that the policy debate on public health hasn’t matured enough to present viable options, and hence it is more likely that the government might opt to spend on “quick-win” schemes such as the UBI or PLI, which are simpler and intuitive at face value. So, on the whole, we should keep a close eye on the government spending trajectory.

PS: Peacock and Wiseman hasten to remind us that their conjecture is not inevitable, the reality depends on the social and economic context of the crisis itself.

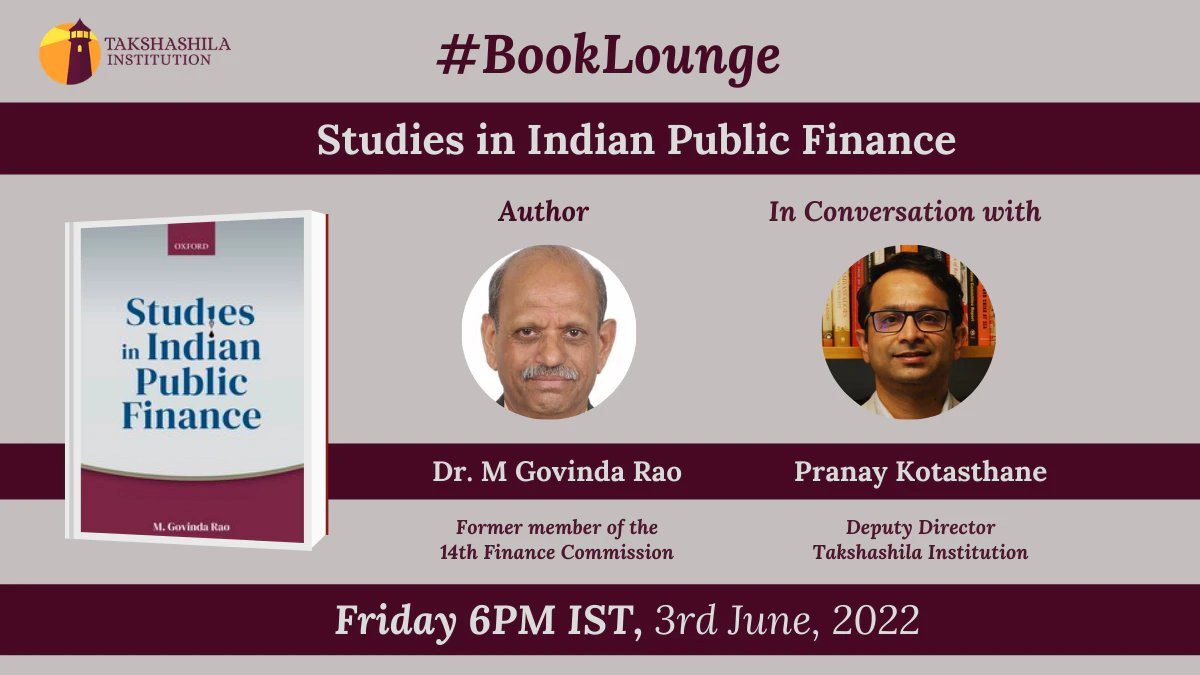

Speaking about PWH, we’re hosting a conversation with India’s foremost authority (and my public finance teacher), Dr Govinda Rao, this Friday. His latest book Studies in Indian Public Finance narrates India’s tryst with taxes, debt, expenditures and budgets. A must-read for any public policy enthusiast.

Global Policy Watch #1: Axel Leijonhufvud On His Tribe

Global policy issues relevant to India

- RSJ

“The Econ tribe occupies a vast territory in the far North. Their land appears bleak and dismal to the outsider and travelling through it makes for rough sledding; but the Econ, through a long period of adaptation, have learned to wrest a living of sorts from it. They are not without some genuine and sometimes even fierce attachment to their ancestral grounds, and their young are brought up to feel contempt for the softer living in the warmer lands of their neighbours such as the Polscis (Political Scientists) and the Sociogs (Sociologists). Despite a common genetical heritage, relations with these tribes are strained-the distrust and contempt that the average Econ feels for these neighbours being heartily reciprocated by the latter-and social intercourse with them is inhibited by numerous taboos. The extreme clannishness, not to say xenophobia, of the Econ makes life among them difficult and perhaps even somewhat dangerous for the outsider. This probably accounts for the fact that the Econ have so far-not been systematically studied. Information about their social structure and ways of life is fragmentary and not well validated. More research on this interesting tribe is badly needed.”

That’s how the paper ‘Life Among The Econ’ began in the September 1973 edition of Western Economic Journal. Written by a young professor at UCLA, Axel Leijonhufvud, the paper was a humorous take on economists as a tribe written in the style of a field paper of an anthropologist. Reading it almost fifty years after it was written, it is hilariously accurate and relevant.

Axel Leijonhufvud died earlier this month. His defining work was his 1968 book ‘On Keynesian Economics and the Economics of Keynes’ where he questioned the validity of the IS-LM model that had become the foundation for applying Keynesian economics. The success of Keynesian economics and the subsequent research on it had made most believe that there was nothing left anymore to discover in macroeconomics. Leijonhufvud proposed a radical departure from this consensus. He called it the ‘cybernetic’ approach that begins with rejecting the notion that the system is in a state of equilibrium. Instead, he argued that the economy is always in a dynamic state which is continually evolving based on initial information available with transactors - their endowments, beliefs, expectations, existing relationships, assets etc. There are a set of possible actions given an initial state and the behavioural rules that will dictate what next step will be chosen. Economic systems, he claimed, operate at a tactical, transaction level with no planned long-term goal. You can study this over time and there will be patterns of behaviour and reference points that will emerge based on the initial set of assumptions but there’s no guarantee things will always converge to an equilibrium.

It was an intellectual challenge to Keynesian consensus and laid the ground for the takeover of the field by the adherents of the rational expectations theory. Famously, his book that theorised at length on macroeconomics didn’t have a single formula. He didn’t need them to make his point. Leijonhufvud believed then (1971) that economics was being taken over by top-down quant models without having an ear to the ground. 50 years later you could argue things have gotten worse.

Anyway, I will leave you with a sample of Leijonhufvud’s dry wit from his anthropological study of the econ tribe.

On status among economists:

“A comparison of status relationships in the different “fields” shows a definite common pattern. The dominant feature, which makes status relations among the Econ of unique interest to the serious student, is the way that status is tied to the manufacture of certain types of implements, called “modls.” The status of the adult male is determined by his skill at making the “modl” of his “field.” The facts (a) that the Econ are highly status-motivated, (b) that status is only to be achieved by making ”modls,” and (c) that most of these “modls” seem to be of little or no practical use, probably accounts for the backwardness and abject cultural poverty of the tribe. Both the tight linkage between status in the tribe and modlmaking and the trend toward making modls more for ceremonial than for practical purposes appear, moreover, to be fairly recent developments, something which has led many observers to express pessimism for the viability of the Econ culture.”

On the primacy of models over everything else:

“While in origin the word “modl” is simply a term for a concrete implement, looking at it only in these terms will blind the student to key aspects of Econ social structure. “Modl” has evolved into an abstract concept which dominates the Econ’s perception of virtually all social relationships-whether these be relations to other tribes, to other castes, or status relations within his caste. Thus, in explaining to a stranger, for example, why he holds the Sociogs or the Polscis in such low regard, the Econ will say that “they do not make modls” and leave it at that. The dominant role of “modl” is perhaps best illustrated by the (unfortunately very incomplete) accounts we have of relationships between the two largest of the Econ castes, the “Micro” and the “Macro.” Each caste has a basic modl of simple pattern and the modls made by individual members will be variations on the theme set by the basic modl of the caste. Again, one finds that the Econ define the social relationship, in this instance between two castes, in terms of the respective modl. Thus if a Micro-Econ is asked why the Micro do not intermarry with the Macro, he will answer: “They make a different modl,” or “They do not know the Micro modl.” (In this, moreover, he would be perfectly correct, but then neither, of course, would he know the Macro modl.)”

On the future of Economics:

It would be to fail in one’s responsibility to the Econ people to end this brief sketch of life in their society without a few words about their future. The prospect for the Econ is bleak. Their social structure and culture should be studied now before it is gone forever. Even a superficial account of their immediate and most pressing problems reads like a veritable catalogue of the woes of primitive peoples in the present day and age. They are poor-except for a tiny minority. miserably poor. Their population growth rate is among the highest in the world. Their land is fairly rich, but much of the natural resources that are their birth-right has been sold off to foreign interests for little more than a mess of pottage. Many of their young are turning to pot and message. In their poverty, they are not even saved from the problems of richer nations-travellers tell of villages half-buried in the refuse of unchecked modl-making and of the eye-sores left on the once pastoral landscape by the random strip-mining of the O’Metrs. It is said that even their famous Well Springs of Inspiration are now polluted. In the midst of their troubles, the Econ remain as of old a proud and warlike race. But they seem entirely incapable of “creative response” to their problems. It is plain to see what is in store for them if they do not receive outside aid.

Global Policy Watch #2: Let Musk Play

Global policy issues relevant to India

- RSJ

Elon Musk couldn’t have existed at any other time in human history. Because at no other point in our history would it have been possible to simultaneously be the richest person in the world, run the most innovative and bold business enterprises, troll powerful politicians and colleagues, show a fine disregard for the law (esp SEC’s laws), smoke a joint on live web TV, create asset bubbles with just a single word and also be seen by millions as a messiah.

A thousand years from today just studying the life and times of Elon Musk would be enough to understand the 21st century. And this would have been true even a couple of months ago. However, that’s not enough for Musk. In the last few weeks, he has gone further. In April, he made a bid for buying out Twitter, the platform that is seen as the global public square of our times and taking it private. Of course, he bid for it at $54.20 per share because he cannot resist a ‘420 marijuana joke’ when he takes these important decisions. And since then, he’s been trolling Twitter. On Twitter. About its management, the likely bots it has as users, its policy on censoring content, its product features and on how its headquarters might be better used a shelter for the homeless. While it is tremendous entertainment for onlookers, there are those who are worried about the implications of a very rich man with strong libertarian and, often strange right-wing beliefs owning the most influential social media platform in the world.

Twitter is already chaotic with bad actors manipulating the platform to trend topics, troll people and create a fake news industry that has ruined lives, influencing elections and creating just about the worst kinds of influencers in countries around the world. The initial euphoria of it providing a voice to ordinary citizens, getting rid of the gatekeepers and the hope of many more Arab Springs have been replaced by a cynicism that it is a platform that can be abused by those with more resources for their political ends. And into this chaotic world, now we will have the king of chaos, Musk, himself holding the reins. This could get really bad.

Or will it?

At the heart of this issue is that old question that Plato tried to answer in ancient Greece. Who should hold power in a society and how should the use of that power be regulated?

There are three key concerns I read about Musk owning Twitter and it is useful to understand them a bit more.

First, there are problems with Twitter today. Bots, fake news, concerted abuse by mobs and somewhat random ways of censoring voices. These issues aren’t helped by its lack of transparency – the algorithm it uses to recommend and trend topics or how it decides on clamping down on certain accounts or tweets are all shrouded in mystery. People abuse the platform for their benefit while Twitter often ends up punishing the wrong guy. Musk has zeroed in on the source of this problem. To him, the platform is optimising for the attention of the user and its algorithms are built to reinforce your biases over and over again. And no one outside of Twitter knows how the algorithm decides which biases will it reinforce and which it won’t. Over time, he fears this lack of transparency will erode trust among users and reduce the effectiveness of the algorithm because of a lack of credible challenge from the outside. He views this as an engineering problem and to quote him – “open source is the way to go” – to solve this. That sounds vague but, hey, it is Musk talking. You can trust him to find the technical solution to this.

Those who oppose Musk buying Twitter are worried that this ‘engineering tech-bro’ mindset has gotten us into this mess in the first place. Musk might be good at putting rockets in space and, possibly, colonising Mars someday but solving a complex social problem is a different ball game. It requires a deeper understanding of people, their motivations and a mind that can think beyond rational expectations and incentives. Giving Musk the charge to make Twitter better is the equivalent of handing the keys of the asylum over to its inmates. That’s the argument.

I’m less than convinced about this. Twitter is a technology platform. Its engagement with its users, its feature of bringing the latest information to your feed and its ability to create a network for you based on how you use it are all products of its technology. The choices it has made on technology have created it in the shape it is today which is different from say, Facebook or Reddit. If the platform encourages click-baits, reinforces biases and tribal loyalties through the like button and optimises for your attention, the solution to it cannot be to solve for human nature. That is an unsolvable problem. This is an engineering problem. Sure, as history has shown once you think you have solved it, the problem will shift. This is an ongoing process in science and every technological innovation has evolved in this way over the centuries. The solution to human mobility has over time gone from horses to cycles to cars to aircraft with each solution bringing with it newer problems. Nobody has ever contended that the real solution is for humans to develop wings.

Two, there is a view that platforms like Twitter are a public good and it shouldn’t be owned by rich, powerful people like Musk. I can grudgingly admit that Twitter is like a public good. But that only means there’s a need for the state to intervene in framing guidelines on how it will be used. It doesn’t necessarily follow that it should be owned by the state. That would be a catastrophic mistake. There’s a long history of media being owned by the rich around the world. The state in most democracies has understood the criticality of media in the scheme of things and managed it well so far. Media moguls have influence but none has ever become a law unto themselves. On the other hand, the state has tried but it has not managed to stifle free speech. We have been worried about this equilibrium for a long time. As far back as 1941, Hollywood was making Citizen Kane about a powerful media owner and his outsized influence on politics and society. Media has only diversified and thrived since. Musk might suffer from a God complex. He might want to be the techno-feudal overlord of the universe. Even if he were to become one, he will still be less powerful than the state.

Three, there is a belief that Musk is a canny operator and perhaps someone who understands the power of Twitter more than anyone else in this world. His reason for owning the platform is to have a free run to do things he likes to do in his spare time – troll the SEC, progressive left and other adversaries in business; pump up meme stocks or dodgy cryptocurrencies, make gains at the expense of his stupid followers and, who knows, probably build a base for some kind of a career in politics. So, Twitter is an expensive toy that he loves. He will play with it till he gets bored. At the end of it, the world will be poorer for his misadventure because Twitter is still an amazing platform for good.

Should he be allowed to run a platform like Twitter to the ground because he has the money and the power? Well, maybe not. But the truth is that he has the power and the money because he has been proven right many times over. There is no divine reason for his magic. He commands trust among his millions of followers because he makes the seemingly impossible possible. Were he to take advantage of that trust to the detriment of his followers, he will begin to lose that power. Musk takes long-range bets – electric vehicles, space travel, EV batteries, hyperloop – and his credibility is the only reason why investors trust him to pull these off. He should know the perils of short-term gains at the expense of that credibility. He will not take a punt on that.

There are market failures that need attention in big tech and social media businesses. Elon Musk buying Twitter won’t make this worse. These failures need policy interventions that regulate the market dominance and the information advantage these companies have. Those are the guardrails that the state and the regulators need to build. The Musk Twitter drama is a sideshow.

HomeWork

Recommended podcasts, papers, and articles on public policy matters

[Paper] Mihir Mahajan and Shekhar Sathe estimate additional deaths in the pandemic years by using publicly available insurance data. TL;DR - the estimates are quite close to the WHO-reported numbers. If you prefer a podcast on this topic, listen to our Puliyabaazi.

[Paper] This old paper asks: Did India’s public expenditure follow the Peacock-Wiseman Hypothesis as a result of the 1962 India-China War? TL;DR - yes, partially.

[Article] Over at New Things Under the Sun, Matt Clancy summarises the literature that investigates the relationship between population and innovation. The evidence suggests that bigger populations are generally better for innovation.

[Podcast] This BIC Talks episode with Faisal Devji on Gandhi is top-notch.

[Paper] For a libertarian critique of the UBI, read Bryan Caplan. “The UBI is a triumph of simplicity over numeracy”, he says. Of course, he is speaking from the American socio-political context.