Global Policy Watch #1: How the Sri Lankan Economy Unraveled

Insights on policy issues making news around the world

— RSJ

What people do when they storm palaces is broadly instructive about what comes next.

In 1792, the French insurgents determined to end whatever remained of the ancien regime stormed the palace of Tuileries and confronted the Swiss Guards who were defending the palace on the orders of Louis XVI. Blood, gore and massacre followed, at the end of which about eleven hundred combatants were killed. These included, as J.M. Thomson wrote in his history of the French Revolution:

..common citizens from every branch of the trading and working classes of Paris, including hair-dressers, harness-makers, carpenters, joiners, house-painters, tailors, hatters, boot-makers, locksmiths, laundry-men, and domestic servants.

The Bolsheviks were not to be outdone on the night of October 25, 1917, when they assaulted the Winter Palace at St. Petersburg on the orders of Lenin. The insurrectionists barely met with any resistance from the yunkers, the Cossacks and the women’s battalion guarding the palace. To quote John Reed from Ten Days That Shook The World (1935):

On both sides of the main gateway the doors stood wide open, light streamed out and from the huge pile came not the slightest sound. Carried along by the eager wave of men, we were swept into the right hand entrance, opening into a great bare vaulted room, the cellar of the East wing, from which issued a maze of corridors and stair-cases.

...One man went strutting around with a bronze clock perched on his shoulder; another found a plume of ostrich feathers, which he stuck in his hat. The looting was just beginning when somebody cried, ‘Comrades! Don't touch anything! Don't take anything! This is the property of the People!’ Immediately twenty voices were crying, ‘Stop! Put everything back! Don't take anything! Property of the People!’

Many hands dragged the spoilers down. Damask and tapestry were snatched from the arms of those who had them; two men took away the bronze clock. Roughly and hastily the things were crammed back in their cases, and self-appointed sentinels stood guard. It was all utterly spontaneous. Through corridors and up stair-cases the cry could be heard growing fainter and fainter in the distance, ‘Revolutionary discipline! Property of the People.’

The Filipinos did things a bit differently on Feb 24, 1986. As this news report suggests:

It started with a rock fight, then the gate was opened for a few photographers and the crowd pushed through into the palace the Marcos family occupied for 20 years, shouting and grabbing anything they could carry. They snatched clothes, shoes, perfume, monogrammed towels. Some wolfed food from the table at which Ferdinand E. Marcos and his family had dined before leaving in American helicopters for Clark Air Base and flight from the country.

Thousands of people were outside Malacanang Palace when the photographers arrived Tuesday night. Supporters of Corazon Aquino, who became president when Marcos fled, and Marcos loyalists started throwing rocks at each other.

They rushed through the gate, turning left to the administration building or right to the living quarters. Marcos loyalists followed them. The fights and looting started. Cheering, the rioters climbed on top of three tanks. One grabbed an ammunition belt. Others took guns.

Cut to present-day Sri Lanka. It has a foreign debt of over US$ 50 billion. Its foreign exchange reserves are about US$ 50 million. Inflation is running at over 50 per cent. The Sri Lankan Rupee has fallen by 80 per cent since the start of the year. What’s worse is that no one knows who is keeping score.

Former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country this week. Right now, he is in Singapore negotiating his asylum with friendly countries in the middle-east (why not China?). His brothers couldn’t get out of Sri Lanka in time. Gotabaya’s military plane didn’t possibly have space for two more passengers. Blood is thinner than aviation fuel. The other forty-odd members of the clan who hold various constitutional and government posts have gone into hiding. The time was ripe for an attack on the Presidential palace. And it happened, as they say, duly.

But this is how the Lankans did the storming (Photos: Arun Sankar/AFP)

To misquote Tolstoy: happy citizens are all alike. Unhappy citizens are unhappy in different ways.

Though unhappy, Sri Lankans look suspiciously upbeat here. So, one thing can be said for sure. There won’t be a revolution in Sri Lanka. The Lankans are a resilient, patient and easygoing lot. They have endured tough times in the past four decades. Now that the Rajapaksas are out of the frame, a national government is likely to be formed; a deal might get worked out with the multilateral agencies involving restructuring of debt, fresh borrowings from friendly countries, and prolonged pain of austerity for the rest of the decade. They will probably muddle through as they have done for much of their independent history. That apart, it is useful to appreciate how Sri Lanka ended up here. There are public policy lessons there.

There are two lenses to apply. The first is the structural weakness in the Sri Lankan economy that has persisted for a long time. Then there is the proximate cause of the recent past that led to sovereign debt default and bankruptcy. We will examine both here.

The Achilles' Heel

In 1948, the British left Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) with an economy that was quite similar to the many similar resource rich nations of the time. Manufacturing was non-existent, banking services were limited to a couple of cities and the mainstay of the economy was the exports of tea and rubber which were vulnerable to commodity cycles. However, it started with a good base of foreign reserve surplus that could cover imports for over a year. With this starting point, the obvious policy measures should have came into play. One, develop a manufacturing sector (public and private) that stimulates growth in the economy and reduces the dependency on imports of intermediates and finished products. Two, to develop the banking sector and create development finance institutions that could provide credit for this transition in the economy.

Neither happened. In fact, the focus on the plantation economy deepened in the decade after independence. The foreign reserve surplus soon turned to a deficit as Sri Lanka continued to import higher-value goods, and the government found it difficult to raise revenues to support its spends as its population increased.

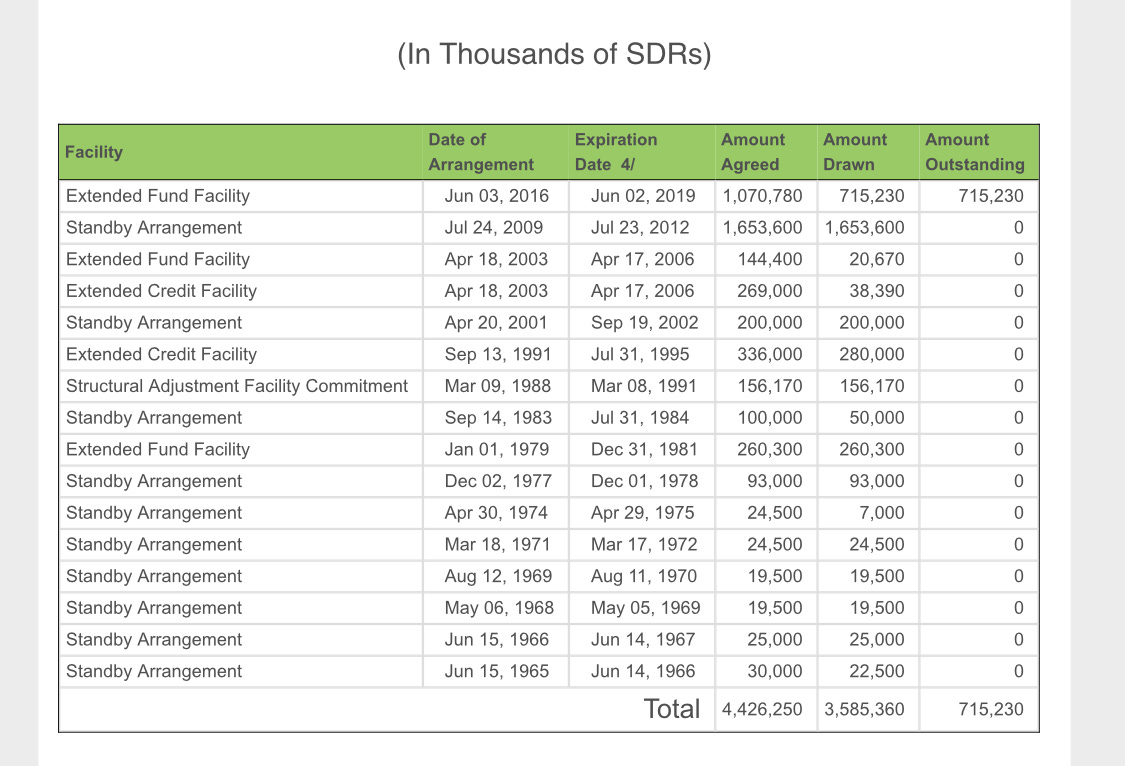

By the mid-60s, Sri Lanka was contending with both a fiscal deficit and a current account deficit. The classic twin deficit pincer that low-income economies get caught in. Over the last six decades, it has struggled to come out of it. The reasons could be many - lack of domestic savings, absence of development finance institutions, inability to attract other sources of foreign capital like direct investment instead of debt and political instability and a long civil war that didn’t help the economy. Things didn’t go badly for Sri Lanka only in the last few years. Its economy was always fragile, as the seventeen different IMF bailout packages that started in 1965 indicate. See the table below for the history of IMF bailouts (SDR = Special Drawing Rights).

The comparison with India during the same period is useful. India chose the more inefficient state-led industrialisation and capital creation model and overdid it by the 70s with the nationalisation of the banks. But it led to the creation of a manufacturing sector and the availability of credit. India also created relatively strong institutions for a developing economy during that time. That meant we avoided a sovereign debt default scenario till 1991. The Indian state, after having generated the initial impetus, should have gotten out of most of these areas by the mid to late 70s. But that’s another story.

Sri Lanka never built that core capacity, nor did it follow the model of the ‘tiger’ economies of creating national champions in select sectors. In the early 80s it ‘opened’ its economy on the behest of the IMF that made these conditions collateral for further bailouts. The dismantling of duties and exchange controls made Sri Lanka even more dependent on imports as its nascent industries couldn’t compete with the foreign goods flooding in. The twin deficit continued to worsen and further de-industrialisation set in.

There are things Sri Lanka is commended for during this time. It has the best HDI metrics in the region, with good quality healthcare and education available to its citizens. These should lead to better economic outcomes, provided the structural issues are addressed. That these metrics themselves were built on foreign debt makes their sustainability suspect. Over-indexing on one measure while avoiding a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis and the unintended consequences is an old public policy error.

Why did things go from bad to worse in the past few years?

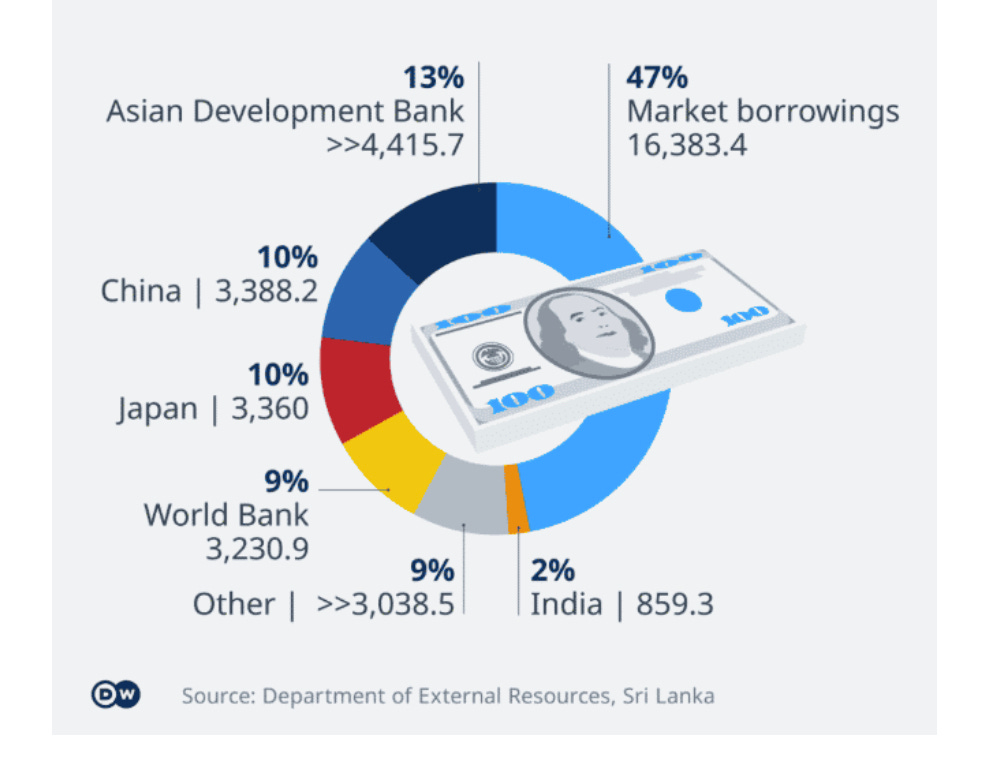

Two things happened. One, the composition of Sri Lankan debt changed for the worse. Sri Lanka issued international sovereign bonds (ISBs) at attractive coupons that got in global fund houses into the mix with more dollar-denominated debt. China, too, got into the game with large infrastructure projects that have ended up as the proverbial white elephants. The chart below shows how its foreign debt stood in 2021.

The market borrowings now contributing to 47 per cent shot up in the last decade. This fresh source of funds further lulled the policymakers. The government continued to spend and feed domestic consumption without a plan to control the fiscal deficit while borrowing to build infrastructure and pay for imports.

In 2019, Gotabaya came into power, promising to reverse these policies. But the ‘strong man syndrome’ took over. There were bold initiatives announced with minimal debates and understanding of likely scenarios that could emerge. Corporate taxes and VAT were slashed in the hope of an economic boost. That didn’t come because there wasn’t an industrial base that could take advantage of this. The fall in tax revenues widened the fiscal deficit and increased the government’s borrowing from the central bank. The pandemic hit tourism, a significant contributor to the economy and a source of precious foreign exchange. The widening current account deficit had to be controlled, leading to another bold idea. The government announced an overnight transition to organic farming and banned the import of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides. There was no real conviction to organic farming here. It was just a means to reduce the import burden and bring the current account deficit under control. The consequences were disastrous. Paddy production fell over 20 per cent, and there was an immediate food shortage. Tea production suffered, and exports fell. Then the Ukraine war sent oil beyond US$ 100 a barrel, which was the last straw. The central bank supplied over US$ 2 billion in the past 12 months to import essential items. But eventually, they all ran out of runway. And we got here.

Of course, Sri Lanka's historical structural weakness is a factor to blame for its troubles. But you cannot take away the hubris of strong man decision-making that aggravated its situation in the last three years. Policy-making requires debates, scenario planning, anticipating the consequences and above all, strong institutions to take an independent, objective view of decisions. Bypassing them and going by instinct might seem like strong leadership, but the odds are stacked against good outcomes coming from them.

Matsyanyaaya: Ignorance Breeds Bias

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

When our level of understanding of another country is poor, we resort to cognitive shortcuts to make sense of the news coming from there. We interpret happenings in a way that reaffirms our current fears, hopes, and anxieties.

While parsing information about a stronger adversary, we start with a sense of awe. When a weaker adversary makes it to the headlines, we start from a position of derision. Similarly, when we interpret information from a stronger ally, we amplify news that shows us in good light with respect to the ally. As for a weaker ally, our starting point is self-aggrandisement.

Excessive reliance on these cognitive blinkers indicates that we don’t know enough about another country. And since we don’t know enough, we cannot differentiate between trash takes and informed opinions, rumours and facts, and between motivated actions and serendipity. It is easy to see these blinkers in action on social media discussions on Indian foreign policy issues.

Take, for instance, what happened in the US earlier this week. House Rep Ro Khanna proposed an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act 2023. Amongst other things, the amendment had these lines:

While India faces immediate needs to maintain its heavily Russian-built weapons systems, a waiver to sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act during this transition period is in the best interests of the United States and the United States-India defense partnership to deter aggressors in light of Russia and China’s close partnership.

The House passed the amendment. Immediately, Indian media and commentariat pronounced that the US had given India a CAATSA waiver. My first reaction was no different. I realised later that this amendment only urges the Biden administration to provide India with a CAATSA waiver since the authority to take this decision lies with the executive branch. Unsurprisingly, there’s not a single mention of this amendment in the top American newspapers (I checked WSJ, WaPo, and NYT). Still, we had already given ourselves a strategically autonomous pat-on-the-back here in India.

There are several other instances as well. In Feb 2018, a 26-member committee of the Pakistani Senate passed a resolution for the promotion of the Chinese language in Pakistan. Within minutes, Indian media was reporting that Pakistan has made Mandarin an official language of Pakistan! Someone just picked up a piece of bad news reporting from a Pakistani YouTube channel and assumed the worst. The sense of ridicule was almost instantaneous, and few stopped to consider how the official language of a State could be decided by a Senate Committee consisting of 20-odd members?

Of course, these cognitive shortcuts are the easiest to find in Indian discussions on China. Because we understand so little about its culture, language, and politics, we almost always solely rely on our preconceived notions. So, we are absolutely confident that the Sri Lankan economy faltered only because of China’s debt-trap diplomacy, that China’s already deployed AI for advanced decision-making in military systems, or that China’s social credit system is a real-life incarnation of the Black Mirror episode, Nosedive. The reality is quite different, but these narratives occupy prime positions in our discourse.

Can we train ourselves to not succumb to these cognitive shortcuts? Perhaps. Political Scientist Yiqin Fu has a really good solution set in the context of poor understanding of China in the US. She proposes four ways out:

Tying more of one’s payoffs to what is happening in the target country as opposed to how news from the target country makes you feel would incentive you to form more accurate beliefs. Participating in online prediction markets or having some exposure to the target country’s financial markets would be a concrete example.

The ultimate solution is to expand your knowledge.. as you can so that you are qualified to judge a wider pool of sellers (commentators).. A realistic approach could be talking to friends or following people with different skill profiles. Together you would be capable of evaluating commentary on a broader set of issues.

Give more weight to commentary that uses systematic evidence… where applicable, the quality of commentary that cites systematic evidence is generally superior to those that do not.

People on the knowledge frontier of any given issue bear special responsibility to amplify analyses they find reasonable, including those that reach conclusions they disagree with. On issues at the intersection of many niche areas, the average consumer has no way of distinguishing between analyses that are “reasonable but different from mine” and those that “rely on complete falsehoods.” So experts ought to share all commentary they find reasonable, regardless of how much they agree with the conclusion.

As a footnote, its useful to consider that the “CAATSA has been waived off” cognitive shortcut indicates one of two things:

some of us are intuitively assuming that US domestic politics has a better appreciation of India’s worldview. And hence, we are ready to jump to the conclusion that the US has already waived off these sanctions. We are seeing what we want to see. Given the chequered past of the US-India relationship, even this mistaken assumption is a positive sign.

However, I think most people are intuitively assuming that India is entitled to a waiver. A lot of Indians are convinced that the US cannot counter China without India on its side. And so, they interpreted the CAATSA amendment news as a reaffirmation of India’s global importance.

It is also interesting to consider if these mistaken assumptions will impact the Biden administration’s calculus on the waiver. Since many Indians are already convinced that India has got a CAATSA waiver, can it now afford to impose sanctions? The answer, of course, depends on a whole lot of other factors. Nevertheless, our cognitive shortcuts about another country reveal a lot about ourselves.

Course Advertisement: Admissions for the Sept 2022 cohort of Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy programme are now open! Apply by 23rd July for a 10% early bird scholarship. Visit this link to apply.

A Framework a Week: Things Governments Do

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

(This post was first published in March 2018 on Indian National Interest)

A typology of government actions can be extremely helpful. Faced with a policy problem, such a typology can serve as a menu of actions that governments can respond with. Various policy solutions can then be seen in this comparative framework:

might action X be the better way to solve this policy problem?

why would the government employ action X over other actions?

what are the disadvantages of using action X over other actions?

Surprisingly, I came across only a few typologies of government actions. One by Michael O’Hare and the other by Eugene Bardach.

O’Hare’s 1989 paper A Typology of Government Action says: all legitimate government behaviour can be classified in eight classes.

Note how this classification does not include things like laws, rules, and procedures — actions that we associate most commonly with a government. The reason is that these three are methods to implement the chosen government action. As such, a law can be a chosen method for many government actions: to prohibit (example: Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006), to tax (example: Income Tax Act, 1961) and to subsidise (example: the Hajj Committee Act, 1959).

Eugene Bardach’s typology in A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis is the second one I came across. It classifies government actions into these categories:

1. Taxes (add, abolish, change rates, tax an externality)

2. Regulation (entry, exit, output, price, and service levels)

3. Subsidies and Grants (add, abolish, change formula)

4. Service Provision (add, expand, organise outreach, reduce transaction costs)

5. Agency budgets (add, cut, hold to last year’s level)

6. Information (require disclosure, govt rating, standardise display)

7. Structure of Private Rights (contract rights, liability duties, corporate law)

8. Framework of Economic Activity (control/decontrol prices, wages, and profits)

9. Education and Consultation (Change values, upgrade skills, warn of hazards)

10. Financing and Contracting (leasing, redesigning bidding systems, dismantle PSU)

11. Bureaucratic and Political Reforms

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Ajay Shah on improving resilience against extreme surges in demand.

[Blog] Noah Smith has an excellent post on the Sri Lankan economic crisis.

[Book] Carrots, Sticks and Sermons — another useful classification of policy instruments

Share this post