India Policy Watch: State Capacity, the Smart Parking Edition

Insights on domestic policy issues

— Pranay Kotasthane

Public policy is all around us; observing the same public space over time can reveal much about public policy, implementation, and state capacity. So, I’ll try something different today. I will narrate the story of a parking policy reform, which I’ve observed closely over the last couple of years. In it are lessons for government contracting, deployment of technology, and public choice. Drop a reply if this story resonates with you or if you have other such anecdata in mind.

The Pre-reform Situation

MG Road is a busy thoroughfare in Bengaluru’s Central Business District. Well-known shops, pubs, restaurants, and offices line the road. As you can imagine, many office-goers and business owners commute to MG Road and park their vehicles next to the curb. On weekdays, finding a vacant parking space after 9 am is a sure-shot sign of divine intervention.

Even though curbside parking is not chargeable nominally, scarcity causes Coasian transfers to originate. An informal cohort of unauthorised Parking Marshalls emerges. These marshalls help vehicle users negotiate parking in return for a fee. After multiple complaints about this “rent-seeking”, the city government puts up free parking boards and demarcates parking bays for two-wheelers and four-wheelers.

A reduction in the real price of parking leads to increased demand. Office-goers rush towards the city centre earlier than usual. The threshold beyond which parking became an ordeal moves up to 8.30 am, after which people have to park about half a kilometre away in a designated paid parking. And since the Traffic Police have no capacity to enforce parking rules except once in a moon, you would usually encounter double-parked vehicles on MG Road, usually cabs. Some shops even employ valets to double-park customers’ cars, which are slid into vacant parking slots as soon as they become available. The motorable road width decreases because of these double-parked vehicles. It is quite a chaos.

The Smart Parking Reform

The paid parking reform had been mooted on several occasions but wasn’t politically palatable. Finally, the city government bit the bullet after the first COVID-19 wave. BBMP —the city municipal corporation—realised that its tax revenue sources had thinned. And with an ongoing hoarding ban and a newly launched GST, revenue generation options had narrowed further. That’s when the Overton Window for paid parking opened up.

Given the lack of state capacity, BBMP doesn’t usually do parking enforcement itself. So it enters into a public-private partnership in which one company Central Parking Services (CPS), is granted a contract for parking on ten major roads in the city’s Central Business District for ten years. Reports suggest that BBMP expected Rs 31.56 crore annually through this arrangement.

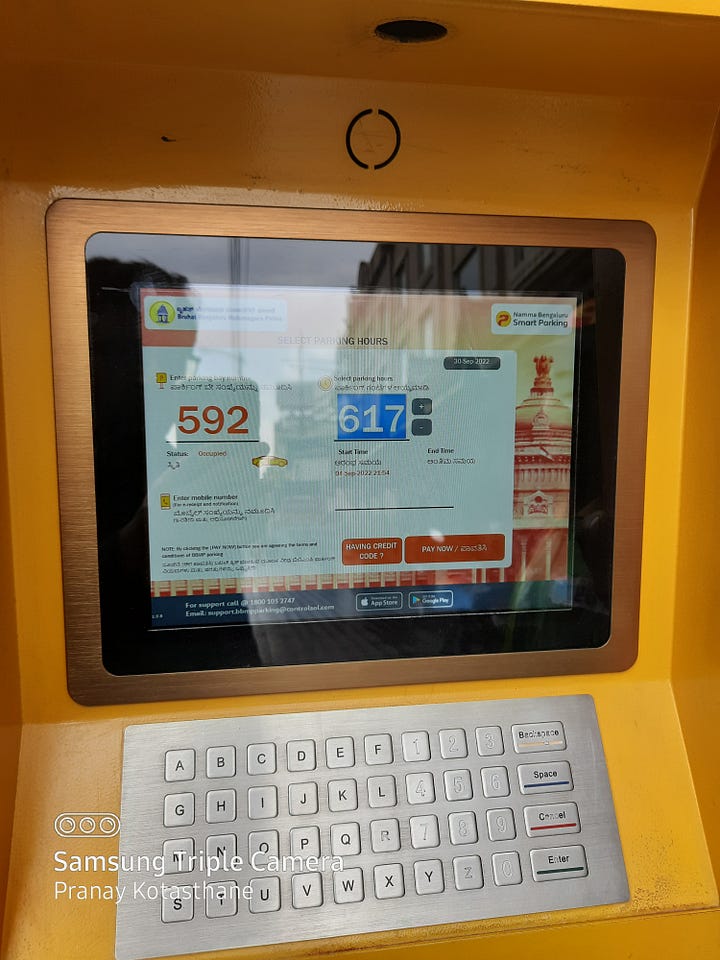

To prevent corruption, BBMP employs technology. Curbside parking spots are clearly marked and numbered. Sensors are installed on each slot to identify the presence or absence of a vehicle. Customers can book a parking slot on arrival via an app and pay seamlessly through UPI/card/or wallet. Parking kiosks are also installed on footpaths for people who don’t have the phone app. To encourage digital payments, cash payments are made costlier by 16.6%, i.e., Rs 30 in cash grants parking permission for 50 minutes, while the same amount paid digitally allows you to book a parking slot for 60 minutes. For a detailed account, see this Deccan Herald report.

To help people transition, parking charges are waived for the first week of operations. Thereafter, cars have to pay Rs 30 per hour.

Now, guess what would have happened? Can you anticipate the unintended consequences?

Post-reform observations

Pricing a resource according to its scarcity leads to a more efficient resource allocation. We saw that scarcity principle play out here. Soon enough, you could find a parking slot at any time of the day. The contractor employed several uniformed parking marshalls to prevent double-parking and unauthorised use. The same road you saw above now started looking as below:

The story doesn’t end here, though. It’s not as if parking requirements are this elastic in the central business district, and it’s not as if the city has reliable public transport options.

What really happened was the displacement of parked vehicles from MG Road to a nearby residential road and a parallel thoroughfare. To avoid paying the parking fee, people started parking vehicles on other roads, sometimes right under “No Parking” signs. These infractions were uncommon earlier as these roads were patrolled by traffic police vehicles. But with the enforcement contracted out to a company in the surrounding area, perhaps the incentive for the Traffic Police to patrol the area decreased, as public choice theory would predict. And so, while the parking situation on MG Road improved, other neighbouring roads became free parking lots, causing congestion and unchecked traffic rule violations.

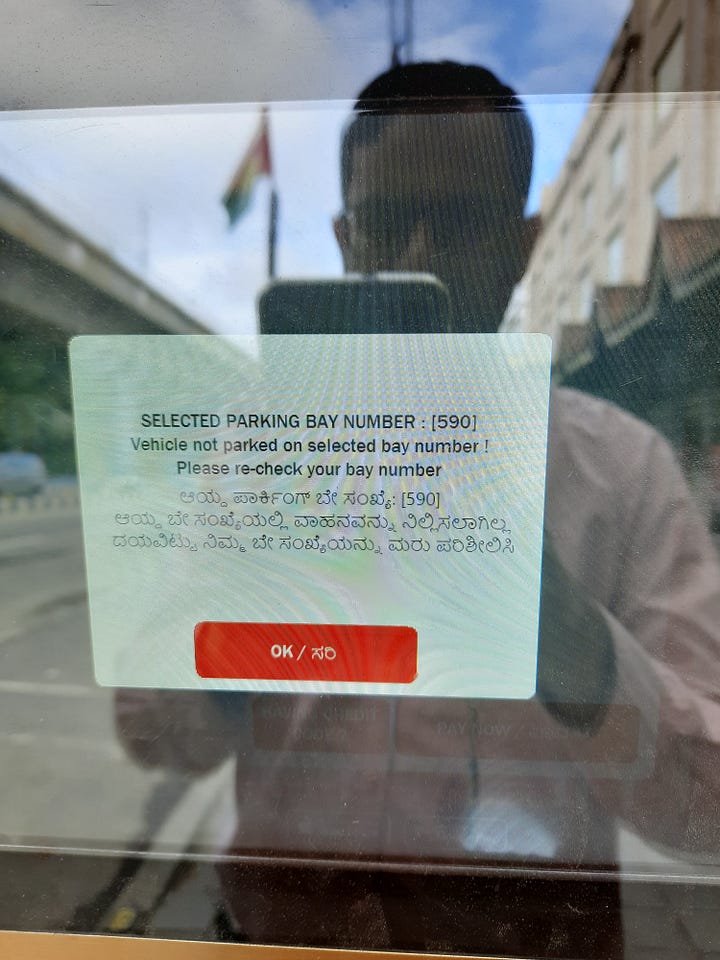

As for MG Road, the “smart” parking didn’t remain smart for long. The sensors for most parking slots stopped working soon. The app and the kiosks showed a parking slot as" “empty” if you parked a vehicle there. At other times, it showed unpaid bills of previous customers. On one occasion, the app asked me to pay a parking fee of Rs 18,290!

Despite repeated calls to the grievance contact number, the contractor didn’t seem to be interested in getting these fixed. The profit motive would have suggested that the company would aggressively keep all sensors active, but that’s not how it played out.

As public choice theory would predict, corruption didn’t go away. The situation was much better than in the past. Nevertheless, since the sensors weren’t working, the Parking Marshalls sensed an opportunity. The system allowed them to reset or extend the parking time limits at the kiosks. Some of them started striking side deals with regular commuters. The parking marshalls also enjoyed discretion in enforcing steep fines for overparking. Since there was no robust check to track fines, they could strike a deal with the customer instead of registering an official fine.

Zooming Out

The marginal benefits of the parking policy reform are greater than the marginal costs; hence, it should continue. But it is still a work in progress. Contracting out doesn’t obviate the need for enforcement entirely. My anecdata reiterates one important lesson in public policy: better contracting or procurement also requires state capacity. Without having built that muscle, contractors can easily take governments for a ride. As Chitgupi, Gorsi, and Thomas write in their LeapJournal article titled Learning by doing and public procurement in India:

Procurement is an expertise. No government organisation can sporadically do this well. It is an expertise which can be built, albeit over many years. In any government organisation, people and processes can be organised to focus on this expertise, and to devote time and effort on the entire pipeline of government contracting. The process of developing this capability can be accelerated by bringing in people with this specialised expertise. Strengthening the entire life cycle is required to successfully spend budget amounts. But this is only the beginning of success in procurement where government can contract to deliver quality projects efficiently, on time and at low cost.

Applications for the re-awesomed Post-Graduate Programme in Public Policy are now open. Check details here.

Global Policy Watch: End Game

Insights on global policy issues

— RSJ

Some recent inflation prints from the US and other developed markets suggest the central banks are winning the fight. In India, too, the inflation expectations are getting less hawkish. Is this true, or is there more to this?

A bit of a diversion here. A few editions ago, I pointed out how the ECLGS scheme launched during the pandemic to support the MSME sector had worked out well in India. The sovereign promised the banks they would guarantee the loans they disburse as part of this scheme. The banks could continue to use their underwriting norms without making them too stringent because of overthinking the negative impact of the pandemic on these businesses. The bank could, therefore, support these businesses, and as it has turned out, that’s all that was needed to keep this sector above water. The government didn’t have to dole out loans themselves, and the banks did what they do well, namely, underwrite, disburse and collect. Net result: the system NPAs for this scheme will end up in the 3-4 per cent range in line with this kind of portfolio in normal times.

I bring this up because while writing about this last month, I thought it would be useful to check if other governments went down this path during COVID-19. It turns out yes, they did. Most of western Europe did the same. Over 60 per cent of new loans in France were guaranteed by the sovereign. In Germany, it was over 40 per cent, and now they have come up with a fresh scheme to stave off the energy crisis emerging from the Ukraine conflict. In Italy, not only were fresh loans state-backed, but they also rolled over older credit to these new schemes. This seems to be becoming a thing.

Governments seem to have hit upon this nice little trick where they don’t have to raise debt or taxes to manage a crisis. They simply need to offer credit guarantee through banks. It will sit on their books as a contingent liability and won’t show up in debt ratios. Nobody gets hurt. Neat.

So, why did I bring this up while talking about inflation? Since the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2009, the debt-to-GDP ratios in the developed economies have only moved one way. Up. Then we had the pandemic in 2020. Governments threw more money at the problem. The result is we have debt-to-GDP ratios upwards of 250 per cent in most OECD countries now. Two problems have arisen because of this.

One, this indiscriminate money supply plus some supply chain constraints have meant inflation has hit multi-decade highs. Notwithstanding all modern monetary theory hypotheses that were in vogue a couple of years back, it turns out that more M4 money in the system will lead to higher inflation. And inflation hurts the poor most. Second, the system is vulnerable to collapsing at such debt-to-GDP ratios with the smallest of shocks going forward. I mean, how long can you keep kicking the can down the road?

So, the inevitable has happened over the past six months. Central banks have raised interest rates in a dramatic manner to tame inflation. This seems to be working, as the slowing of headline inflation number suggests. But I am not sure about it. Most of the recent reduction comes from the fall in prices of the more volatile commodities. In fact, the ‘sticky’ part of the consumption basket seems to be still in inflationary mode. Also, the rising rates have killed growth in most developed economies. They are in a recession. And while the employment data suggests that jobs are being added, if you look closely, the worm is beginning to turn. The slowdown across sectors will mean layoffs, consolidation and a reduction in capital expenditure. The employment rate will soon start falling.

With that backdrop, what are the choices available to a government? I see a likely scenario that brings these various tugs and pulls together for a short-term fix that might appeal to them. I will elaborate below.

Now that inflation has touched multi-decade highs, and we are at that point in the rate hike cycle where we have pretty much killed growth in the short term, there isn’t more elbow room to increase rates. Inflation may subside a bit as supply constraints reduce, and maybe the war in Ukraine ends. But this is an opportune time for governments to reset inflation expectations upwards among its people.

If you were running an inflation targeting model with a two per cent threshold (like in the US), it is somewhat easier now to raise it to 4-6 per cent without much furore. If you were running it at a 4-6 per cent range (like in India), you could reset it to 6-8 per cent. The Overton window is available for this. I think the governments will willingly take it. A slightly higher inflation expectation, without it becoming runaway, will allow central banks to pause raising the rate. It will also increase nominal GDP. This is important because a two per cent upward reset of the inflation target will lead to a corresponding increase in the nominal GDP. And increasing nominal GDP through higher inflation is the easiest way to reduce debt to GDP in the system for a government. Cutting costs and tightening the belt are all difficult ways of balancing the budget. Nobody wants to do that. In the past, letting inflation run high was unacceptable to any incumbent government. But the way the cards have fallen in the last six months, the governments can get away by citing forces beyond their control. I think no government will look this gift horse in the mouth. They will reset inflation targets. Now doing this means what’s called financial repression. That is, the savers will lose because their savings will be undercut by inflation in future. So, this will have to be done gradually. But I see this level of financial repression as inevitable.

The success of credit guarantee schemes opens another front for governments. As I mentioned, the governments will do more of this because why not? So, in some sense, you will see a capture of private credit by government-directed guarantee schemes. It won’t be as much in India, but I see it quite likely in the developed economies. So, it is likely that while the economy will head to a recession, private banks will continue to supply credit because of these sovereign guarantees. There’s a likelihood that bond traders will take a dim view of this and push up yields significantly. But there are multiple tools with the government to force pension and insurance companies to buy government bonds. This will rise. Yield curve management isn’t a big deal anyway if central banks decide to do it. So, no fear on that front too. This will mean we could have continued credit expansion backed by the government in the near future without the fear of a rating downgrade. If you combine that with the developed economies bringing manufacturing back from China into their own countries, we could have a capex-led boom beginning soon after we have brought inflation into the new target limit.

Of course, I’m not saying I support this kind of state intervention that pushes credit in the areas it wants to focus on instead of the market allocating capital in the most efficient way. In the long run, the state will make the wrong choices driven by its political objectives. But we will have to wait for the cycle of boom to first play out before that kind of bust unfolds. This might take a decade or maybe more. I am, therefore, sceptical of those who suggest a deep recession or stagflation is around the corner for the global economy. There will be a short recession, but other options are available for the state to manage this and push a real reckoning into the future.

Stagflation might be the end game, but that end is not nigh.

HomeWork

[Paper] Internal Drivers of China’s External Behaviour by Amb Shivshankar Menon is really helpful in understanding China’s recent actions. This line in the paper struck me (There’s a useful 2x2 matrix in it):

“Today, China faces an unprecedented situation at home and abroad and is therefore reacting in new ways. China is more powerful than ever before but is also more dependent on the world. This is an unprecedented combination, not known in Chinese history—not in the Han when she had to ‘buy’ off the Xiongnu by marrying Han princesses off to steppe leaders; nor in the Song when she was one and sometimes the weakest power in a world of equals; nor in the high Qing when she was powerful but independent of the external world, as the Qian Long emperor reminded George III in writing.”

[Book] The High Costs of Free Parking by Donald Shoup is essential reading on parking policy.

[Paper] Which social welfare policies should the Indian government prioritise? This paper does a cost-benefit analysis to answer this important question.