#263 Beyond the Obvious

The Indian State vs 'Godmen', India-China Comparisons, and the Russia Trip policyWTF

India Policy Watch #1: Omniabsent State → Omnipresent Babas

Hot takes on burning public policy issues

— RSJ

More than 100 people, almost all of them women, were killed in a stampede at a satsang (religious gathering) on July 3. The event was organised by the followers of Narayan Sakar Vishwa Hari, or Bhole Baba, a self-styled ‘godman’ who has built a cult in western UP districts of Mathura, Etah, Shahjahanpur, Kasganj and Hathras.

The reasons for stampede include the usual litany of administrative failures that have made such events death traps in India. Poor planning—instead of the 80,000 followers that were supposed turn up, more than 225,000 turned up; absence of crowd management protocol for such events—the space was cramped and barricaded, the surface was uneven and when there was a rush to collect the ‘charan dhool’ (literally, the dust on which the Baba had walked), a few women fell and that led to a cascade of people getting trampled over; and lastly, the almost total absence of any emergency medical support at events because none among the organisers or the local administration believes something like this will happen despite multiple pieces of evidence to the contrary in India over the years.

For a country with a population like ours with multiple instances of large congregations, we devote very limited time and resources to the policy issues around crowd management. It is no surprise that we have stampede-related deaths reported every year across India where the basic principles of crowd management could have avoided the loss of lives of ordinary citizens. In fact, given the risks involved, our attitude towards safety and the number of such events in India, we must thank our stars that we get away with fewer than expected tragedies.

While the public policy failure in managing such events is evident, it is the other success that’s of interest to me for this edition. What explains the tremendous success of babas and godmen in India? What makes someone who was a police constable a couple of decades ago turn into a miracle worker with a cult following who can gather over 200,000 people to listen to him speak on a weekday afternoon during a particularly harsh north Indian summer? Faith or superstition is the ostensible reason.

But the failure of the Indian State is the real one.

In our book Missing in Action, we write about how the Indian State is simultaneously omnipresent as an oppressive presence in the lives of its citizens and ‘omniabsent’ in not being there for citizens when and where it truly matters for them. The Indian State is spread too far to meddle with almost everything the ordinary enterprising citizens would want to do and too thin to be effective in anything it tries to do for them.

Three specific failures of the Indian State have encouraged cults of these kinds to develop over the years. This trend has accelerated in recent years, contrary to the belief that with rising education levels, scientific awareness, and a relative increase in prosperity, fewer people should believe in superstitions and miracles.

Consider the case of Bhole Baba, a Dalit godman who apparently sought no offerings or money and whose primary following is among Dalits and backward caste poor women. Many among them have spoken of the two things that he offered them - a sense of hope that their current miserable lives (and even afterlives) will be better if they followed him and a promise of social dignity and kinship by being together as his followers which they otherwise don’t have. The success of political representation among Dalits and other historically disenfranchised sections is often described in glowing terms in Indian politics. Unfortunately, and not unexpectedly, the political success in representation hasn’t translated to a massive change in the social lives of these communities. Because the political representation eventually settles in to take the shape of the Indian State, and once that happens, there is only so much that the State can do to change the lives of these sections.

This isn’t mere rhetoric. This is precisely what has happened. Greater political representation for Dalits in north India has coincided with a preponderance of miracle workers, sanghs and deras that encourage their followers to drop their caste surnames, shun traditional gods in favour of human alternatives, involve them in some kind of society-building measures (construction of a school or hospital) to give a sense of purpose to their coming together and rope in more followers into the cult. This is what political representation should have enabled. But it didn’t. The State has continued to fail in improving their social representation, delivering real equity, and reducing ongoing anxiety about who will support them when things go south. Babas fill in the vacuum.

The second failure is that of delivering basic healthcare services to the poor, even in the not-so-remote locations in India. Secondary or tertiary healthcare is a distant dream there. Miracle cure of chronic ailments is often the primary draw of these godmen. Because for these citizens, secondary care is either inaccessible or they are simply priced out of it. So, the choice is either a godman whose mere touch or a blessing cures you that others have vouched for, or there's a quack who puts up a tent in your town or village and offers you natural cures for all kinds of illnesses. The trigger for the Hathras stampede was the rush of the followers to collect the ‘charan dhool’ of the baba which reputedly had miraculous healing powers. Anyway, both these business models have done well because the structural issues in healthcare, especially the prohibitive cost of medical education and the limited number of medical seats in India mean there aren’t enough doctors for the society, and there’s no incentive for any doctor to set up a practice in the Indian hinterland. The NEET examination fiasco is another consequence of the same issue.

Lastly, there’s a school of thought that believes the re-emergence of religion in our political discourse after years of trying to keep it out of it and pursue some kind of Indian secularism is for the broader good of the society. Religion has a central role in the lives of Indian people, and the active effort to keep it out of politics as envisaged by most of the founders of the Indian State only helped it morph into a more virulent suppressed political form. That’s the logic offered by those who believe that civilisational Hinduism, or its equivalent, as championed by the dispensation that’s been in power for the past decade, is for the good of Indian society. Hence, the ever more religious overtones to so many constitutional and political events in our lives during this period. Even the opposition has become part of this project, as was seen in the recent session of the Lok Sabha when even the LOP led his speech with a picture of Shiva with his various qualities apparently serving as a guide for his political actions. Now, there is a belief that citizens who watch these displays can distinguish between the performative and the spiritual aspects of these acts of their leaders. But it isn’t always easy to make such distinctions. More often than not, and this is borne by evidence across the world over time, people see these acts by leaders as validation for whatever form of religion - benign, superstitious or virulent - that they like to follow. And this will only deepen in India because there is no political currency for scientific temper (as outlined in Constitution) or some kind of spiritual reawakening that the more sophisticated proponents of religion in politics claim. Anyone speaking in those terms will lose politically.

For now, Bhole Baba will join the long list of infamous godmen as the usual stories of his alleged excesses and sexual shenanigans show up in the media. But there is a longer list of Babas flying under the radar right now with a possibly larger following than him. And there are more waiting to get in on the game.

When the state is ‘omniabsent’, babas become omnipresent.

India Policy Watch: Six India-China Comparisons

Hot takes on burning public policy issues

— Pranay Kotasthane

Earlier this week, Martin Wolf’s well-regarded FT column argued that India is on its way to becoming a superpower—and the poorest one at that—by 2047. The operative paragraph is here:

“Moreover, and crucially, India has strengths. It is an obvious “plus one” in a world of “China plus one”. India has good relations with the west, to which it is strategically important. But it is also important enough to matter to everybody else. It could be what the IMF calls a “connector country” in the world economy. Indeed, it can and should lead in the liberalisation of trade, domestically and globally. India also has the advantage of its diaspora, which is enormously influential, especially in the US. Not least, India’s human resources give it the capacity to diversify and upgrade the economy over time. It must exploit this. Size, in short, gives the country weight. India is not just constrained by the world: it can and must shape it.” [Martin Wolf, FT]

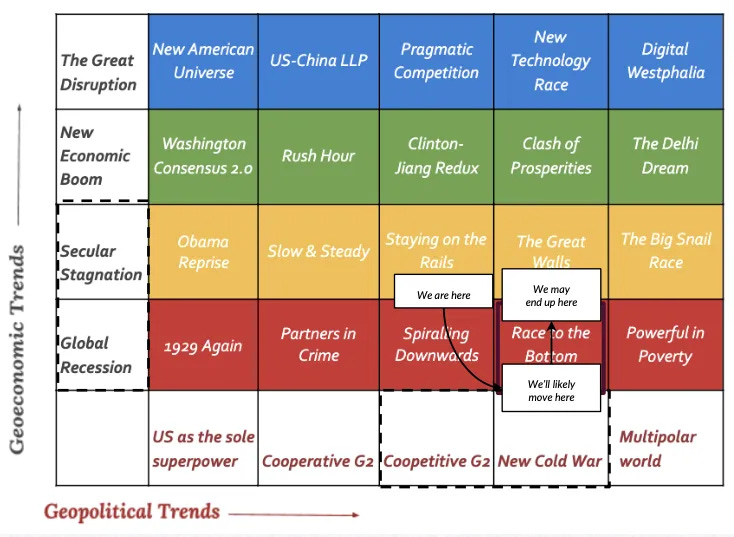

The article also hints at some trends that might spoil the party for India: the global economic slowdown, rising protectionism, and the climate crisis, to name a few. Long-time readers will recall that we had developed scenarios to understand such trends and their impact on India in the book India's Marathon: Reshaping the Post-Pandemic World Order.

Such projections inevitably lead to India-China comparisons. Comparing the two economies today is not helpful in most cases simply because China is almost five times richer than India. That one intermediate variable explains most of the sector divergences.

Not only is China’s output higher, but it is also able to assemble more inputs than India can. For instance, it has more active military personnel, a threefold defence budget, more engineers, factories, doctors, etc. Not surprising.

But wouldn’t it be far more interesting to compile a list of economic inputs that India already has in abundance, yet their resulting output is smaller than China’s? Such a list would identify domains that are the proverbial low-hanging fruit; the problem in such domains isn’t chronic resource scarcity but about converting these inputs into outputs and outcomes.

The most apparent input domain is population. But let me go a step further and list six other specific paradoxes.

Agricultural resource endowments: From this week’s The Economist:

“Although India has a third more land under cultivation than China, it harvests only a third as much produce by value, according to analysis by Unupom Kausik of Olam, an agri-business listed in Singapore.”

Medical Colleges: India has the highest number of medical colleges globally, yet China produces 3.5 times the doctors India produces yearly. China had 420 “undergraduate institutions with medical education” in 2018, while India managed to establish 706 medical colleges by 2023. Indian colleges offer 1.09 lakh undergraduate seats, while China’s output is nearly 3 lakh doctors every year. We have covered the reasons for this discrepancy here.

Vaccine Capacity: India is the world’s largest vaccine maker. Yet China exported five times the number of COVID-19 vaccines India could export.

School Teacher Salaries: Indian teachers in government schools are much better paid than in China, yet China beats India in student learning outcomes. Teacher salaries (specifically in government schools) are three times the per capita GDP in India. But a better pay scale doesn’t translate into better teaching.

Diaspora: India’s diaspora (18 million) is nearly twice as large as China’s (10.5 million). Indian immigrants have done exceptionally well for themselves and their host countries. Due to this diaspora, India’s inward remittances are higher than any other country's. Yet, the Chinese diaspora performs better in terms of research spillovers. Chinese immigrant researchers are likelier to co-author papers with colleagues back home than Indians. These co-authorship networks have helped Chinese universities climb the scientific ladder faster.

USFDA-approved Pharmaceutical Plants: India has the largest number of FDA-approved plants outside the US. Yet, China’s pharmaceutical industry exports nearly three times more by value than its Indian counterpart.

Are there any other input-output pairs of this nature that I’ve missed? Drop us a comment.

Matsyanyaaya: The Tail’s Wagging the Dog

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

Rarely have I been able to classify any foreign policy move as a policyWTF. On that front, India has done rather well. But the PM’s visit to Moscow comes close.

The PM landed in Moscow just a day after a missile strike on a children’s hospital in Ukraine, at a time when the partners India needs for countering China were discussing Ukraine at the NATO Summit. And it wasn’t as if the outcomes were significant either. Apart from the bear hug pictures, the outcomes document has zero wins for India. India couldn’t even insist on getting the “Indo-Pacific” mentioned in the joint statement. Nor was there any mention of “territorial integrity” and “sovereignty”, terms the Indian PM has often deployed in the Ukraine-Russia context. Surely, this is anything but “strategic autonomy”.

The timing of the visit and the dud joint statement indicate that the visit’s primary purpose was to send a signal to the US and the West. It does seem that the transnational repression allegations have strained India-US political relations considerably. To the extent that India is demonstrably cosying up with Russia. The signal is that the West could lose a partner in its competition with China if it decides to press the matter further.

A few tough days lie ahead for India-US relations. As for the India-Russia relations, the matter isn’t about what India got out of the visit, but rather that Russia hasn’t much to offer. Russian investments in India are insignificant; tourist flows have been declining. Cut off from critical global supply chains due to export controls, Russia has no new high-technology wares to distribute. If anything, oil imports sharply increased India’s trade deficit with Russia. To think that a weakened Russia would come to India’s rescue is letting nostalgia displace realism. The tail is wagging the dog.

HomeWork

Public Policy Content That You Mustn’t Miss

[Article] Check out Brian Albrecht’s post on a paper applying price theory to understand opioid demand. I wish there were more papers such as these in the Indian context.

[Article] Rajesh Rajagopalan’s clear-eyed take on the PM’s Russia visit.

[Post] Our answer to the question: Aap Hamaare Hai Kaun, Russia?

Thanks Pranay - the India/China comparisons are a nice way to look at low hanging fruit. I wonder if any of these 6 areas are intentionally being worked on. And if not, why not?

To complete the assessment though, I think its also worth looking at the flip side i.e. sectors where India has a comparative advantage say services exports - ensuring that the policy environment remains supportive to sustain this advantage is as important as working the low hanging fruit.

The critique of the Prime Minister's visit to Moscow reflects a profound bias towards Americanism, lacking a nuanced understanding of India's strategic imperatives and long-standing diplomatic relationships. Firstly, dismissing the visit as merely a "policy WTF" undermines the complex calculus that underpins India's foreign policy decisions. The assertion that the timing of the visit, coinciding with a NATO summit, signals a rift with the West is simplistic. India's foreign policy operates on the principle of multi-alignment, balancing relationships with major global powers to safeguard its national interests.

The writer's expectation for India to align unequivocally with the West ignores the geopolitical realities and the historical context of India-Russia relations. For decades, Russia has been a reliable partner, particularly in defense cooperation. This relationship cannot be reduced to immediate transactional gains or the lack thereof in a single visit. Moreover, criticizing the absence of terms like "Indo-Pacific" and "territorial integrity" in the joint statement reflects a superficial understanding of diplomatic negotiations, which are often influenced by the broader strategic context and ongoing dialogues.

The commentary also disregards India's sovereign right to pursue an independent foreign policy. Suggesting that India's outreach to Russia is a mere signal to the West undermines India's agency and strategic autonomy. It is crucial to recognize that India's engagement with Russia is not solely about what Russia offers in the present but also about maintaining a diversified foreign policy portfolio to avoid over-reliance on any single bloc.

Further, the writer's fixation on strained India-US relations due to transnational repression allegations misses the broader picture. India and the US share a robust strategic partnership that transcends temporary disagreements. The realpolitik of international relations involves managing differences while continuing to cooperate on shared interests, such as countering China's rise.

Finally, the critique's pessimistic view of Russia's current economic state and its implications for India is myopic. Strategic partnerships are not only about immediate economic benefits but also about geopolitical stability and long-term strategic interests. India's increased oil imports from Russia, for instance, reflect a pragmatic approach to energy security amid global volatility.

In sum, the commentary reflects a one-dimensional perspective that prioritizes alignment with the West at the expense of a more balanced and strategic approach to India's foreign policy. The complex interplay of global diplomacy demands a more nuanced understanding that transcends binary narratives of alignment and opposition.