#265 Self-correction

China's Role in India's Manufacturing, Defence Budget Highlights, Bye-bye Biden, and Reading Recommendations

India Policy Watch #1: China, Padharo Mhare Des

Insights on current policy issues in India

— RSJ

A mixed bag of topics to write about this week. There’s the Economic Survey and the Budget presented by the NDA government, and the state of the US presidential race.

Let me start with the section of the Economic Survey that made me sit up and re-read the whole thing again. Here it is:

“.....it may not be the most prudent approach to think that India can take up the slack from China vacating certain spaces in manufacturing. Indeed, recent data cast doubt on whether China is even vacating light manufacturing. The questions that India faces are: (a) Is it possible to plug India into the global supply chain without plugging itself into the China supply chain? and (b) what is the right balance between importing goods and importing capital from China? As countries attempt to reshore and friendshore, India’s policy choices concerning China are exacting.”

Pragmatic and pointed. Like much of the Economic Survey this time.

It goes further:

“Developing countries will have to figure out a way of meeting the import competition from China and, at the same time, boosting domestic manufacturing capabilities, sometimes with the collaboration of Chinese investment and technology.

India has a similar decision to make, given its large bilateral trade deficit with China. It makes India vulnerable to potential abrupt supply disruptions. Replacing some well-chosen imports with investments from China raises the prospect of creating domestic know-how down the road. It may have other risks, but as with many other matters, we don’t live in a first-best world. We have to choose between second and third-best choices.

In sum, to boost Indian manufacturing and plug India into the global supply chain, it is inevitable that India plugs itself into China's supply chain. Whether we do so by relying solely on imports or partially through Chinese investments is a choice that India has to make.”

Kamaal hai.

Listen, the chasm between what’s suggested in the Economic Survey and the real world of policymaking is quite wide. We know that. But to have cleared ‘god knows how many reviews’ and to have got this sort of plain speak into the Survey deserves appreciation. It has got people talking. A good attempt, if there was ever one, at shifting the Overton window.

All through 2020-21, when there were border skirmishes with China, we argued for being pragmatic about the economic measures we take against China and keeping it a bit removed from our political line. Granted, the two cannot always be sharply segregated, but we advocated prudence over jingoism in our economic relationship with China. Then, like it is today, we had three core arguments favouring our stand. Over the last three years, data from both India and China have only made these arguments stronger.

Firstly, the dominance of China across multiple global manufacturing value chains makes it impossible for domestic manufacturers in India to decouple from them. Either they will reroute Chinese components from other countries or have to find alternatives from the developed world. Either way, it will make the domestic producers uncompetitive in terms of prices. And there’s no way, given the low maturity of our manufacturing sector, will we be able to make these intermediates ourselves any time soon. We have seen the impact of import substitution in the past. You get inferior products at higher costs. So, the die was already cast on this decision to distance ourselves from China economically.

Since 2020, we have only approved a quarter of total FDI proposals that have come from China and done our best to make imports from China more onerous. And what have been the results of this? In the five years since 2018-19, our exports to China have remained stagnant at around $16 billion, while our imports from China have raced to $101 billion from $70 billion. This should surprise no one. Countries don’t trade with one another. People do. And if they have strong economic reasons to do so, they will take all hurdles you place in their stride. The bottom line is the same traders who clap at their TV screens when news anchors go on about PM Modi showing “red eyes” to China, then wake up the next morning and place orders from Chinese companies. Left to itself, we will continue to see a surge in trade deficit with China, which will make us and our companies more vulnerable to arbitrary actions by its government.

Secondly, China is sitting on an economic crisis of its own and as much as it might enjoy needling India on its borders, it also needs us. To cut a long story short, China is unwinding its massive over-investment in real estate and infrastructure sectors that drove its growth in the past decade or more. Much of it was speculative, and there’s real pain from the high level of indebtedness resulting from this. The obvious lesson from this experience was to put a lid on investment-led growth and then balance their economy by focusing on greater domestic consumption. But that’s hard work for many reasons. The most important one is how to do this rebalancing without inflicting huge pain on its people in an economy that’s still on the ground floor of being a middle-income one. The absence of democracy and a quasi-dictatorial regime doesn’t help either in having real debates about the economy and the kind of bitter pill it needs to swallow.

These have led China to revert to its old playbook. Go big on manufacturing again. It has built humongous overcapacity in the green energy sector and is now looking to export it worldwide to fuel its growth in the same model that worked for it in the first decade of this millennium. The problem is that the developed economies have learnt their lesson this time. China is struggling and will continue to find it difficult to export this overcapacity so easily this time around. The second-best option for it is to set up production facilities in the markets it wants to access. This reduces the risks of a ballooning trade deficit with China and creates employment opportunities in the domestic market. The US and much of the Western world are possibly closed to this option because they have their own manufacturers to protect and revive. So, China is looking for markets, and there’s no bigger emerging market than India, which is also looking to make a green transition. It needs the Indian market. We can, therefore, have Chinese FDI into India on our terms.

Lastly, having more Chinese companies setting up factories and making mega investments in India shifts the risk to them. Once they are in with their investments, they are on the hook and vulnerable to our policy regime. This is a point that Swaminathan Aiyar made back in 2020. It is risky for others to put money in India and they will have to weigh it with the advantages of cheaper labour and a large market in India. We don’t have to do anything except ensure we keep a few strategic sectors out of it and ensure these companies follow our data privacy and safety laws. This option works more in our favour than the ever-spiraling trade deficit with China.

I hope the Economic Survey leads to some rethinking in this area. Given our continued employment challenge (which is highlighted by the Economic Survey, too), we need much stronger manufacturing sector growth, especially in the ‘lighter’, more labour-intensive industries. We have more to gain than lose in this reset.

Regarding Budget 2024 itself, I don’t have a lot to write about. It was mostly meh. A fair degree of continuity in keeping fiscal discipline, some special packages for the states run by the coalition partners, an apprenticeship programme that might take care of skilling issues in the long run but won’t address the more fundamental challenge of creating jobs, a bit of TDS reform and random tinkering on taxation on capital gains that make no sense except to signal that we like to tax the rich. Nothing to see here. Move on. The Finance Secretary reiterated the last bit about taxing the rich in his interactions with the media. If that’s something to go by, this is a strong early signal that one of the lessons learnt by the BJP from the elections is to go down the good old socialist, redistributive ‘garibi hatao’ plank.

It is a bad idea, both economically and politically, for a party in power.

Addendum

— Pranay Kotasthane

Long-time readers will recall that our stance on Chinese investment has been on the same lines as the Economic Survey 2023-24. I want to highlight a few excerpts from earlier editions which explain our case.

In edition #199, we classified the government’s preliminary approval to 14 of Apple’s 17 Chinese suppliers for setting up joint ventures in India as a step in the right direction. In other words, a Not(PolicyWTF). We wrote:

Back in 2020, we had written that tightening the FDI rules for all sectors is a policyWTF. Existing FDI rules back then already had restrictions on foreign investments in strategic sectors. To overlay this reasonable condition with a region-specific ban on investments across sectors didn’t make sense.

Given this backdrop, the small opening the government has now offered to Chinese suppliers of Apple is a positive course correction.

It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but there’s just no other way to achieve the stated goal of creating $300 billion in electronics manufacturing by 2026, with overseas sales of $120 billion, than to engage Chinese manufacturers.

In edition #222, we argued that achieving stated targets in electronics manufacturing requires a “re-coupling” between Indian and Chinese businesses on three dimensions: chips, investments, and talent. We argued for two policy shifts then:

One, distinguish between the Chinese governments and Chinese businesses. Indeed, the Chinese Communist Party’s controlled economy means that Chinese businesses have less agency than their counterparts in the US or India. It is also true that China’s aggression on the border and adversarial positions at multinational fora show that it sees a growing India as a threat, not an opportunity. However, it is also important to note that Chinese businesses—especially suppliers to other multinationals—have different incentives than the CCP. Outside a narrowly defined set of strategic sectors such as defence and telecommunications equipment, investments by such businesses in India is a net positive.

Chinese investments can also give us foreign policy leverage. Economist Swaminathan Aiyar’s recommendation “massive foreign investment is a bigger risk for the foreigner than the investee country. So, let us attract as much Chinese investment as possible, since the main risk will be theirs, not ours.” needs deeper deliberation beyond simplistic binaries.

Two, the Indian strategic establishment needs a sharper definition of what constitutes “strategic”. It is insufficient and counterproductive to define entire sectors as strategic. Not all types of chips or LCDs are strategic. They cannot be used to harm an adversary. Dependence on China for these items does not make it a strategic vulnerability for India. If imported chips and Chinese investments into electronics assembly is what India needs to accelerate its journey, they accelerate, not impede India’s growth.

Earlier this week, Business Standard reported that three companies—Tata Solar, ReNew, and Avaada Electro—had sought the government’s permission to issue visas to 36 Chinese engineers to help them set up solar module manufacturing. We dealt with this issue earlier in edition #261:

One of India’s largest conglomerates is waiting for government approvals to permit travel of Chinese engineers who can train Indian staff to ‘Make Electronics in India’. And even this small ask has become a political hot potato.

This, to me, is a perfect illustration of what is likely to happen once we start going down the path of increasing barriers to trade with China. We need to contend with the fact that Chinese talent and investment are crucial elements of the global electronics supply chain. Even firms such as Apple have a large supplier base in China. Of the 188 companies in its supplier list, 151 are Chinese or have a substantial manufacturing presence in China. There is absolutely no way for India to build an electronics ecosystem quickly without accessing Chinese investment, talent, and commodity chips.

It would be terrific if India could put in place fine-grained barriers specifically against Chinese products in sectors where India has competing firms. But from what we know about the Indian State, such a strategy is most likely to spill over into other sectors where India has no competing firms, and turn into an all-out denial regime towards Chinese companies. This will hurt India far more than China, as we account for just 3 per cent of Chinese exports.

Though we have consistently argued for a selective recoupling of Chinese and Indian economies, we do not think China’s political stance and military posture towards India will change anytime soon. The Economic Survey’s assessment has led some observers to make over-optimistic extrapolations about a political rapprochement between China and India. Some even think that the Russia-India-China (RIC) grouping might rise from the ashes, spurred by the prospect of another volatile Trump presidency. That hardly seems to be the case.

The CCP doesn’t consider India an equal. It is unlikely to reduce political and military pressure on India. If anything, it will only become more antagonistic towards India as the power gap between the two neighbours reduces. In a 2015 Takshashila Discussion Document that Dr Anantha Nageswaran (the current Chief Economic Advisor) and I had written, we made a point that has stood the test of time thus far:

China’s strong growth (backed by the US) over the last four decades had made it see itself as a power that would challenge the US. However, if it’s economic power declines (and that of India’s grows), the vast gap between India and China will start reducing. This means that China might become more aggressive in its dealings with India. A China that declines as a global power will have fewer tools to operate with, but it does not mean that it will be friendlier to India. Hence, India will have to invest in building its economic power and diplomatic capacity so that it is rightly placed for the time when China confronts India as an equal.

Thus, resetting economic ties is required only because it is imperative for India’s economic story, not in the misplaced hope that it will reduce political friction between the two countries.

Global Policy Watch: Bye-Bye Biden

Global policy issues relevant to India

— RSJ

Back in January, in my annual prediction post, I had this as my first prediction:

“President Biden will decide sometime in early February that he cannot lead the Democratic Party to power in the 2024 elections. He will opt out of the race and give possibly the most well-backed Democrat, financially and otherwise, a really short window of four months to clinch the nomination. In a way, this will be the best option for his party. If he continued to run for the 2024 elections, it would have been apparent to many in the electorate that they are risking a President who won’t last the full term. If he had opted out earlier, the long-drawn primary process would have led to intense infighting among the many factions of the party, eventually leading to fratricide or a Trump-like populist to emerge perhaps. A narrow window will allow the Party to back an establishment figure and reduce the fraternal bloodletting.”

Well, I had taken President Biden to be a better man than he turned out to be. Instead of doing this in February, he bowed out of the race only last week after a disastrous debate performance and a stubborn reluctance to read the writing on the wall. The Democrats now lag in most battleground states, the Republicans have received a donation surge after Trump’s assassination bid and a convention that displayed coherence and unity (not things you associate with Trump), and there’s barely any time to find a nominee except to anoint Kamala Harris at the Democratic convention next month. For someone who has had almost 50 years of distinguished public service and a fairly decent presidential term, I’m afraid Biden will be mostly defined by this delay, which made the path easier for a second Trump term.

Multiple theories are floating around about why he didn’t make this decision earlier. From a deep state running things behind the scenes to his inner circle led by his wife (Lady McBiden?) wanting to hold on to power, there’s an entire gamut of them. I have a simple theory about this. At the close of their careers, all politicians start to think about their legacy. This is pure hubris, of course. You don’t define or create your legacy. Eventually, history does. But hubris is natural to a politician. For Biden and his inner team, the legacy they had set store in their minds was this - the man who stopped Trump, not once, but twice. And took America back away from the brink.

I’m almost certain everyone on his team knew it wasn’t about lasting a full second term with all his faculties working at levels that befitted the role of president. Their only focus was to hope he was fit enough to last this campaign, beat Trump, and then, a year or so down the line, step down, stating he was placing his country above himself. Everyone then stands up and applauds. And he cements his legacy. Unfortunately, Biden’s health deteriorated faster than they expected, although it was clear to everyone else.

It was a gamble. It is what politicians do all the time. It is what Joe Biden has done most of his life with tremendous success. The key to this game is to not lose your last gamble. Because in this game Joe Jeet Wohi Sikander (he he).

Unfortunately, Joe lost his. And that will be his legacy.

India Policy Watch #2: The Defence Budget Round-up

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

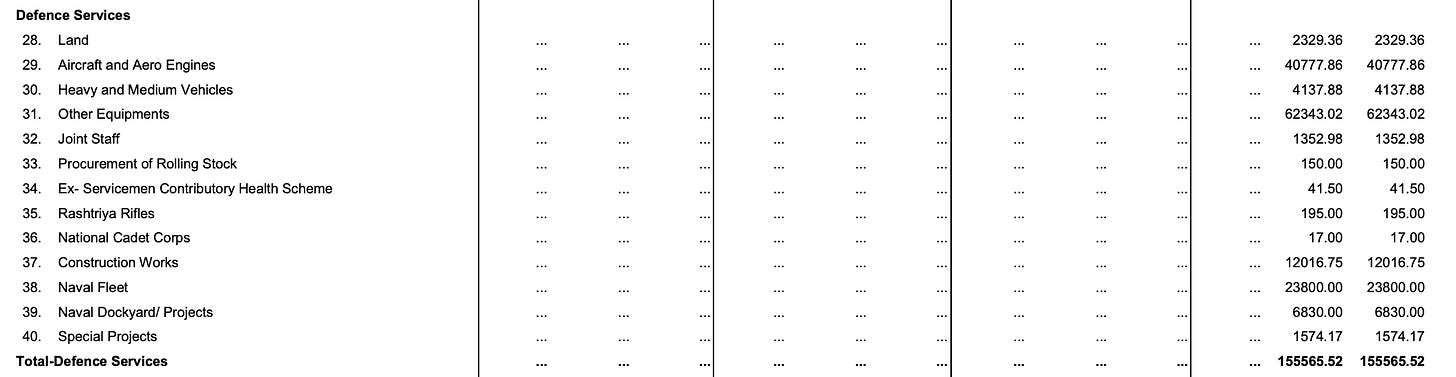

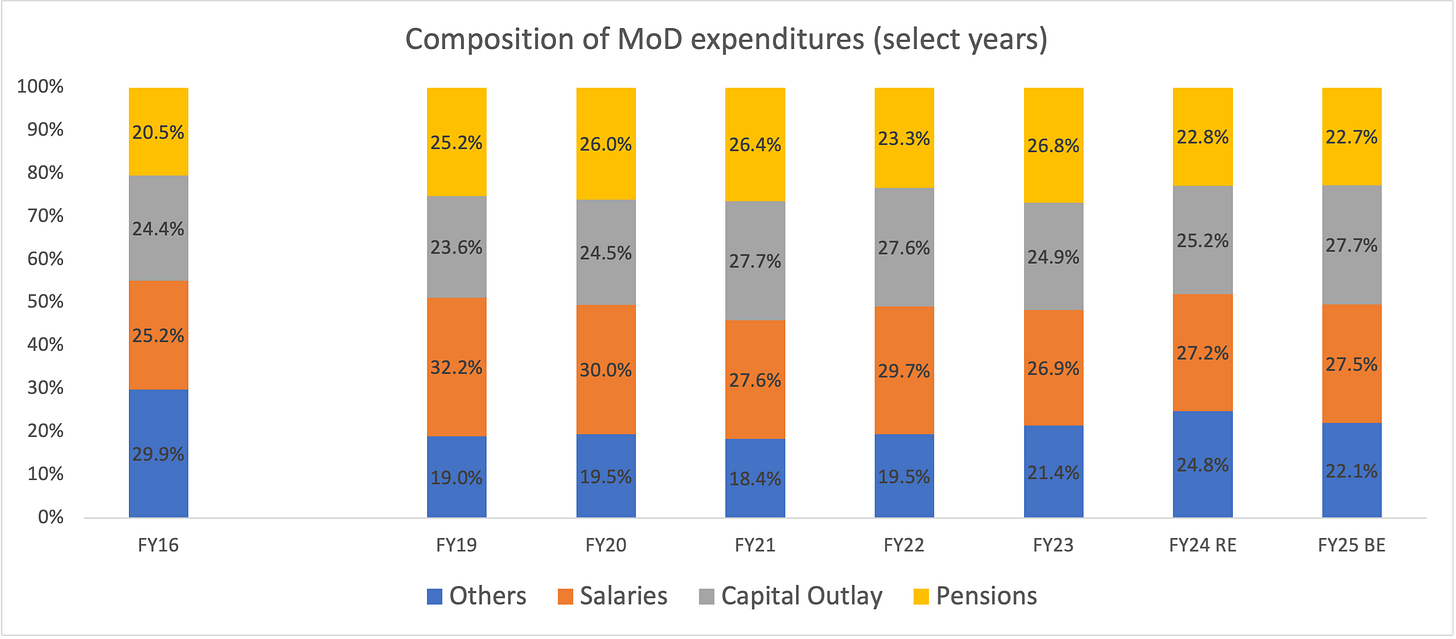

Every year, I write about the defence budget. Because that domain is shrouded in secrecy, it faces little scrutiny. For instance, consider the fact that the government has stopped reporting the split-up of the expenditure on arms purchases across the three services. Until the intermediate FY25 budget, the government shared this data with the public, which allowed analysts to create charts of this nature:

Starting this financial year, creating such a chart is no longer possible. The budget only reports platform-wise lumpy numbers that combine the capital expenditure across the three services. Something like this:

Some people have suggested that this indicates a move towards joint procurement and theaterisation. However, that is an incorrect inference. Even with theatre commands in place, the demands placed by the three services will determine the expenditure on arms procurement. Hence, they will continue to be budgeted as separate line items for the three services.

A simpler explanation might be that the ministry didn’t particularly enjoy some reporting on the three forces' capital expenditures and decided to do away with the underlying data itself. I might be wrong about this, and I will happily revise my claims if there are better explanations. But for now, it seems like the MoD has done what the Education Ministry did with the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2012—if a number shows you in a poor light, make that number go away. ना रहेगा बांस ना बजेगी बांसुरी.

That apart, the defence budget wasn't spectacular. Defence expenditure as a proportion of the union government spending and as a proportion of India’s economy continues to decline. It is now projected to be below 2 per cent of the GDP this year. That didn’t prevent the MoD’s press release from claiming:

“In the Regular Union Budget of Financial Year (FY) 2024-25, Ministry of Defence (MoD) has been allocated Rs 6,21,940.85 crore (approx. US $75 Billion), the highest among the Ministries.”

That’s putting a brave face on, but I’m old enough to remember that excluding interest payments, MoD expenditure has been the “highest among Ministries” for a really long time. After all, defence is the prime constitutional responsibility of the union government.

The budget's one positive aspect is its focus on improving the capabilities of maritime and land border protection forces. The capital outlay for arms procurement has also increased by 9 per cent over the revised estimates of the previous year, indicating a major platform deal might come through this year.

It seems clear to me that the government has decided that the China challenge needs to be managed through non-military means. Perhaps the government considers other tools of statecraft — diplomatic, economic, or non-conventional — more suitable for the purpose. We can only hope that it is busy sharpening these tools even as defence spending continues to decline in relative terms.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

— Pranay Kotasthane

This time, we have a slightly expanded section because there’s lots of good stuff to share.

Drop whatever you are doing and listen to Planet Money’s episode titled “How Flying Got So Bad (Or Did It?)”. It’s an epic story that illustrates how de-regulation operates. We often have an irrational fear of de-regulation in India. We think that without having the government as an active player (and not just a regulator), markets become rapacious, matsyanyaaya reigns supreme, and all of us small fish become menu items for the big fish. However, this episode brilliantly explains the benefits of de-regulation through the change in the nature of American airline operations over the decades. Flying in the past was way more luxurious but waaaay more costlier than what it is today. There is, of course, a flip-side to it, as one of the hosts ponders:

Maybe this is a bigger moral about the trade-offs that come with the economy as a whole. Like, we embrace an ethos of deregulation. It meant that things became cheaper. And also, then they started to feel cheaper. That is the trade-off.

Speaking about de-regulation, one chart in the Economic Survey really struck home. It showed how overtime rates in India are exceedingly high, while the working hour limits in a factory are quite low. Business Standard had an excellent chart that puts the two observations in perspective.

The net result is that companies must hire more people and pay every employee substantially more for extra work. We have first-world regulations at third-world incomes, resulting in a situation where incumbent employees benefit at the expense of those who are left unemployed as capital moves to other countries with reasonable regulations.

These observations are thanks to a series of papers by Prosperiti, which highlight mind-numbing manufacturing regulations that have crippled India’s growth story. How can India’s manufacturing become competitive with the boondoggles that are still in place? That’s the question that Chapter 8 of the Economic Survey asks. It’s well worth reading.

Another must-read for this week is a short essay by James C. Scott, who passed away this week. His work has inspired many scholars we admire. Reading this essay, appropriately titled “Intellectual Diary of an Iconoclast,” will immediately tell you why that is the case. We will someday do a Puliyabaazi to inform our audience about Scott’s work.

Speaking of Puliyabaazi, check the episode with Akshay Jaitly on the link between power sector reforms and India’s energy transition. (Don’t forget to subscribe to the channel!)

Finally, three short, online, cohort-based courses are on offer at OpenTakshashila that will interest you—one on Space Power, another on Life Science Policy, and one on Sports Governance. These are cutting-edge topics in public policy, so do check them out and get equipped.

@RSJ, you referred to deep state.

What do you think of deep state? Does it exist? Is it a conspiracy theory?

I have asked about the same here: https://opentakshashila.net/posts/military-industrial-complexmic-and-the-deep-stateds?utm_source=manual