#281 Causes and Reasons; Effects and Impacts

The Q2 Growth Figures, A Framework for Sustainable Policy Change, and a Question on the US' policy self-goals

Course Advertisement: Intake for the 40th cohort of the Graduate Certificate in Public Policy Course (GCPP) closes soon. The GCPP will equip you with policy fundamentals and connect you to over five thousand people interested in improving India’s governance. Check all details here.

India Policy Watch #1: Why the Decline in Q2 Growth?

Insights on current policy issues in India

— RSJ

The GDP print for Q2 came in last week, and to the surprise of no one except the government and the central bank, it was a shocker. The economy slowed to a growth of 5.4 per cent, a seven-quarter low, driven by sluggish consumption and a sharp slowdown in industrial growth (7.4 per cent y-o-y growth in Q1 to 2.1 per cent in Q2).

The fiscal spending was low in H1, thus impacting fixed asset investment, which in turn meant low demand for steel, cement and construction materials. Personal consumption was weak because of continued macro-prudential tightening by the central bank that has led to credit growth coming down from 16-17 per cent to 11 per cent over the last four quarters. We have written earlier about how tight liquidity and an excessive focus on reining in food inflation have led to credit drying up for retail consumers. Timing is everything in managing these variables and our opinion has been that the central bank jumped the gun here. Those tracking high-frequency indicators of the economy and the corporate sector results of Q2 were raising the sceptre of a slowdown for some time. But no one heard them.

Back in edition #274 (Sep 29), while analysing the fiscal package unveiled by China, we had written:

“Looking at China’s economic issues at this time presents a fascinating contrast with India, where the central bank has kept liquidity really tight over the past two years, tried to dampen loan growth by increasing risk weights for banks for unsecured loans, and has signalled that credit growth cannot be higher than deposit growth in the banking system. These are all countercyclical measures to tame inflation, prevent the possibility of asset bubbles building up and keeping powder dry in case global macro gets worse. All of these will start impacting growth soon, if not already.

If China is a case of too little too late, maybe India is doing too much too early.“

The Government put on a brave face, expressing optimism for H2 and cautioning against over-interpreting the Q2 numbers. Some blame was laid on the doors of disruption in the global supply chain and on the global environment not being conducive to growth. But that’s ignoring the real reasons.

Anyway, I can see fiscal spending improving in H2 and some relaxation on controlling food inflation now that some big state elections are out of the way. But the consumption indicators in Q3 have remained weak, and there’s only been a marginal uptick in other high-frequency indicators. The government has signalled the annual GDP growth will come in below the earlier estimate of 7 - 7.2 per cent to about 6.6 per cent. I think we will end up there if everything else falls in place. This is because, given where food inflation is (over 6 per cent) and that the central bank cannot unwind the policy interventions that led to monetary tightening so quickly, we will continue to be in a low liquidity environment. Also, the post-Trump global trade flows can be quite volatile if one were to take his promises on import tariffs at face value. While the clamour for central bank action on cutting rates shot up following the dismal Q2 GDP numbers, it is difficult to imagine an immediate rate cut with these headline metrics. The strong dollar over the past few months has also meant limited elbow room to pump in liquidity through forex interventions. All in all, whether we acknowledge it or not, we have painted ourselves into a corner, and it will take a few quarters to find a way out of this.

Speaking of currency, there’s also a limit to the interventions that the central bank can make to hold the Rupee stable. The Rupee has been the most stable EM currency in the past four quarters thanks to a hyperactive defence of it by the RBI. The Rupee volatility index has been about 600-700 bps lower than the EM currency volatility index (~10 per cent). This level of currency management is unprecedented. Over the past few months of defending the Rupee, the FX reserves have decreased from over USD 700 bn to a little less than USD 650 bn. This is still a comfortable FX level and provides the central bank with the ammunition to defend the Rupee longer if needed.

But the question is, why does it need to defend the Rupee so vigorously? The FX reserve build-up over the past couple of years has been aided by a favourable movement in balance of payment (BoP) because of the continued rise in FDI and the good inflow of FPI money last year coming on the back of India’s inclusion in global bond indices. This is already slowing down—FPI inflow is almost done, FDI repatriation is at an all-time high as PE/VCs cash out, and the fiscal measures taken by China have meant at least a temporary switch of EM funds away from India. Given these stresses on BoP, the usual Trump-related uncertainty on tariffs and oil price volatility remains high, and the Rupee continues to defend against the odds to signal some kind of economic stability and pride, which doesn’t seem prudent. Moreover, businesses and investors have gone easy on medium-term hedging against currency volatility, with the central bank signalling its intent to defend Rupee. Why incur the cost of a forward when the government is doing everything to manage the currency volatility? Like in the earlier case of liquidity tightening, even the continued support to Rupee has gone on for a bit longer than necessary, and it will make sense to let it slide and leave the volatility for businesses to manage themselves. Overmanaging currency fluctuations almost always leads to second-order implications that come back to bite later.

Considering these factors, it was no surprise that the monetary policy committee (MPC) that met this week decided to hold the rate unchanged but reduced the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) from 4.5 per cent to 4 per cent. CRR is the fraction of liquidity reserve that the commercial banks must keep with the central bank as a prudent stability measure. A 50 bps cut means there is about Rs 1.3 trillion released for the banking system to lend onwards to its customers. This reversal of tightening should boost credit growth, which has seen a consistent downward trend in the past four quarters. The question is, given the higher risk weights and other policy interventions already done, is this infusion of liquidity too late? Already, there are signs of credit stress in the MFI, gold and personal loan sectors where the level of indebtedness has gone up significantly, and a sudden change in policies has meant banks are holding back on lending even to good-quality customers. There might be a need to do more to get credit growth back on track. The MPC committed “to remain unambiguously focused on durable alignment of inflation with the target” which in simple English means the 4 per cent target remains the North Star for policy actions. So, any rate cut is still some distance away, and the government and the central bank will have to use other tools to ease liquidity and spur growth. The options here aren’t too many.

Lastly, the recent results in state elections give the union government a lot of breathing space to manage the tightrope between growth, inflation and currency stability. The economic performance, or lack of it, doesn’t seem to be of voters' primary concern while voting for the BJP (or, to be fair, any other party) so long as a combination of welfarism and nationalism works in tandem with local caste equations. This apparent divorce between economy and politics is strange but can possibly be explained by how low the political parties have managed to keep voters' expectations on the economy on account of their efforts. That a low GDP print, like in Q2, spurs policy action almost immediately is, therefore, a pleasant surprise. Despite everything, it would appear that growth matters. And that’s some solace.

P.S. In 1991, the then finance minister Manmohan Singh’s response in the Rajya Sabha addressing the fears of devaluation of the rupee needs a revisit:

“Let me say that in this country there seems to be a strange conspiracy between the extreme left and extreme right that there is something immoral or dishonourable about changing the exchange rate. But that is not the tradition. If you look at the whole history of India’s independence struggle before 1947 all our national leaders were fighting against the British against keeping the exchange rate of the Rupee unduly high. Why did the British keep the exchange rate of the Rupee unduly high? It was because they wanted this country to remain backward and they did not want this country to industrialise. They wanted the country to be an exporter of primary products against which all Indian economists protested. If you look at Indian history right from 1900 onwards to 1947, this was a recurrent plea of all Indian economists—not to have an exchange rate which is so high that Indian cannot export, that India cannot industrialise. But I am really surprised that something which is meant to increase the country’s exports and encourage its industrialisation is now considered as something anti-national.”

A Framework A Week: What Makes a Policy Chance Stick?

Tools for thinking about public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

A section of Punjab and Western Uttar Pradesh agricultural land owners is threatening another protest. This group is demanding a legal guarantee for Minimum Support Price (MSP), debt waivers, pensions for farmers and farm labourers, no hikes in electricity tariff, and the withdrawal of police cases. On the back foot, the Union Agriculture Minister has already stated in the Parliament that all produce will be purchased at MSP.

How the winds have changed! In 2020, the government tried to push three bills allowing the sale of farm produce to players outside APMC, relaxing stocking restrictions under the Essential Commodities Act, and enabling contract farming. Then came the massive protests and the rollback of these bills. Today, those reforms have been buried deep, and the government is merely trying to hold its ground in the face of demands diametrically opposite to reforms. What began as an attempt to transform India’s agriculture has, within four years, brought us to a place that’s taken us several steps behind the starting line.

We have written several posts on the Farm Laws fiasco (#94, #97, #148, and #184). However, this post focuses on a framework that can help us distinguish policy changes that work from those that don’t.

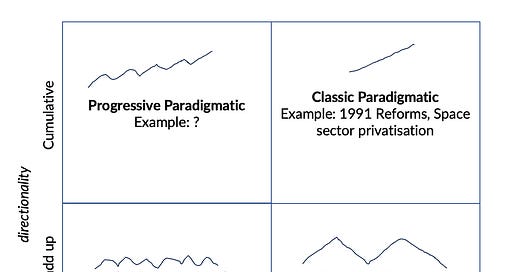

Cashore and Howlett, in a paper on super-wicked policy problems, have developed a useful taxonomy for policy change and its prospective stability. The 2x2 framework’s first axis is the tempo of the change—some reforms are a series of incremental policy changes, whereas others attempt a step-jump or “paradigmatic” alteration. The second axis is the cumulative directionality of the reforms—do the changes accumulate and move the system to an entirely new equilibrium, or are they just fluctuations centred around the status quo?

Using these axes results in four kinds of policy reform mechanics.

In this framework, the Farm Laws of 2020 would be classified as “faux paradigmatic,” where a swift change in policy was reversed and sent back to its original position and beyond. In contrast, the upper two quadrants have policy changes that add up together, moving the system to a new equilibrium.

Another interesting difference this framework highlights is between the two left quadrants. Some incremental policy changes do not add up, and policy inertia returns the domain to the old equilibrium, while some progressive changes do add up to a transformative change over time.

In their 2012 paper, Overcoming the Tragedy of Super wicked Problems: constraining our Future Selves to Ameliorate Global Climate Change, the authors argue that “super-wicked” problems like climate change can only be tackled through progressive paradigmatic policies, i.e., slow changes that add up over time.

A search for a one-shot “classic paradigmatic” policy change is often impractical, particularly because such problems are not caused by a single entity or action but by the cumulative actions of several individuals. A single policy intervention cannot address the multifaceted nature of the problem. Moreover, super-wicked problems are also characterised by the absence of a central authority capable of enforcing a one-shot global solution. Thus, the authors argue that tackling such problems means committing to a series of steps that trigger a path-dependent process. In their words:

“.. the purpose of an ‘‘applied forward reasoning’’ approach is to identify ways in which interventions might create particular policy pathways that move toward preferred outcomes. Our approach is complementary to, but distinct from, other scenario-building efforts, which attempt to identify logics and take into account contingencies that could lead to different futures. Instead, we focus specifically on policy logics that may trigger and nurture path-dependent processes that lead to transformative change over time.”

To bring about a progressive paradigmatic policy change, changes must trigger the following path-dependent processes:

Lock-in: a policy intervention has immediate durability, making it difficult to reverse. In other words, the policy has “stickiness”.

Self-reinforcing: the costs of reversing a policy increase over time. In other words, support for the change increases over time.

Positive feedback: support for a policy expands beyond the initial target population in ways that reinforce the support of the initial population.

It is striking that the Farm Laws—although necessary—met none of the three conditions above and ended up being faux paradigmatic reforms.

I struggled to identify examples of progressive paradigmatic policies in the Indian context. Do you know any? Send us a comment.

P.S. RSJ had a post long ago on ways to engineer a choice architecture for the public that can address the tendency to fabour short-term maximisation. Some of his recommendations are quite close to the “progressive paradigmatic” approach. Read about them here.

Global Policy Watch: Explaining American Policy Self-Goals?

Insights on global issues relevant to India

— Pranay Kotasthane

As an Indian well-wisher of the idea that America represents, one question bugs me: what explains the US making so many policy blunders in recent years?

Whether it is the advocacy of protectionist tariffs in the economic domain, the support for anti-immigration and anti-abortion policies in the social domain, or allowing Israel to dictate terms in the strategic domain, the US seems to be making quite a few choices that go against its national interests.

From an Indian perspective, I find this quite puzzling. When the government makes policy blunders here, we instinctively focus on two reasons: a lack of state capacity or the absence of data or epistemic knowledge about the problem. However, none of these issues exist in America. It is home to the world's best knowledge and talent base across virtually every field, and it also possesses high state capacity. And yet, it seems to be making counterproductive policy choices repeatedly in several fields at once.

So, what could be the reasons if knowledge and state capacity aren't the issue? I can make three guesses. The first answer is social media. Like in India, the social media ecosystem in the US could have triggered hatred towards the elite and the experts, making extreme opinions travel further.

The second reason could be that despite being home to the world’s smartest people, their ideas never reached a broader audience; they merely stayed within their professional circles and elite publications.

A third reason might be that every nation-state or generation needs to discover its own truths over time. Perhaps every good idea has an expiry date, and every bad policy idea is resurrected, even in advanced countries like the US.

This question is an open thread in my mind. What do you make of the policymaking environment in the US? What explains its self-goals?

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Ajay Shah has a useful framework in this article on an outgoing FDI strategy for Indian firms.

[Paper] This paper on policy dynamics is insightful.

[Article] Sarthak Pradhan and Pranay explain the leverage points to improve India’s corporate R&D performance in this Deccan Herald opinion piece.

This is wrt your open question on US policymaking. My 2 cents below:

#1: A major policy driver for the US is the fear of China's rise. On that front, I feel Clemenceau's quote (Generals always prepare to fight the last war, especially if they had won it) applies here. The Americans are framing policies wrt China as if it is the former USSR, i.e., military foe with no economic weight and little integration into global trade. Since China is none of those (militarily much weaker than US, economically a giant, and the mfg line for everything in the world), copying the Cold War strategies is just dumb.

#2: The US got used to being the country everyone admires. Now there are too many countries that don't look up to the US. The soft power is eroding slowly, but many of its policymakers don't seem to get it.

#3: The world is getting multipolar. If they put sanctions on Iran or Russia, they need to give exceptions to India and China. The Ukraine war evoked support only from the West; India and China were granted exceptions; and the rest of the world didn't care. Adjusting to this complex reality where everything has feedback loops of increasing complexity isn't easy.

#4: America has increasingly weaponized its currency to impose unilateral sanctions and evictions from SWIFT. All of this makes other countries nervous and rumblings of alternate systems become more attractive, if nothing as a safety net.

#5: All of the above situations are complex enough. To add to that, America now elects people (Biden, Trump) who are too old to understand or adjust to such dynamics.

Either the framework or your application to policies is not making much sense to me. I'll need to read the paper to understand the framework, because your explanation is not clear. Also, it looks like in the bottom-right quadrant, you can add any policy change that got reversed, either fully or partially, which does not seem very useful.