#295 The Moment of Reckoning

Un-popular Culture; Israel and the Perils of the Proportional Representation System; and the Electronics PLI Just Got More Complicated

Course Advertisement: Intake for the 9th cohort of Takshashila’s 48-week Postgraduate Programme in Public Policy (PGP) is open. This course is aimed at professionals who want to switch careers to public policy. Details here.

India Policy Watch #1: No Laughing Matter

Insights on current policy issues in India

— RSJ

Two strands of Indian popular culture that have been strengthening in the past decade came together last month.

One, “ahistorical” fiction that has meant novels and films that recast past events to favour current political narratives reached its commercial peak with Chhaava, a semi-fictional account of Sambhaji, who succeeded Shivaji to the throne of the Maratha kingdom. While the opportunistic template of a Hindu king fighting against an ogre-like Muslim “invader” had lost some of its steam in the past couple of years owing to amateurish productions starring Akshay Kumar, I was sure there was an audience for a well-made film doing exactly the same convenient rewriting of history with great leaps of imagination. All you needed was a tighter screenplay and the right dose of Hindu victimhood that eventually triumphs, and you would have a blockbuster on hand. Chhaava did just that. It isn’t great filmmaking to me, and its politics has barely any conviction because it refuses to acknowledge the nuances and failings of its central figure. But it does the filmy and political blend of masala right, and that has meant box office magic. Hindi films and OTT shows have already taken a turn where the plot and dialogues are either to exploit the trend of the revised narrative of our history or have to be scrubbed clean of anything that portrays the current dispensation in a poor light. Self-censorship is the most evolved form of suppression of free speech, and we are getting good at it.

Two, we have also seen the state target standup comics and shut down shows because of what it considers vulgar or politically motivated content. We had the unseemly spectacle of FIRs and court cases filed against the show “India’s Got Latent” and YouTube creators Samay Raina and Ranveer Allahbadia, which led to the closing down of the very popular channels run by both of them. The Supreme Court called the content condemnable and dirty and asked, “if this is not obscenity in this country, then what it is?" Well, the short answer to that question is this news item where large amounts of cash was recovered from the residence of a Delhi Hight] Court judge. All we have so far is the constitution of a three-member committee by the Supreme Court and the transfer of the judge back to Allahabad High Court. No observations of the kind the Court had about Allahabadia - “there is something very dirty in his mind which has been vomited”. And last week, we had another comedian, Kunal Kamra, being threatened with physical violence with multiple FIRs filed against him for a new video where he made jokes mainly about the current Maharashtra ruling coalition. The members of the aggrieved political party attacked the venue where the show was held, and later, the Mumbai municipal corporation demolished it for some random infringement. Indian comedians have a very limited space left for content that won’t bring harm to them. Religion and politics are out, and barring a handful, most comedians have eschewed these topics. Risqué or outré stuff was already curbed and will vanish after India’s Got Latent outcry. All we are left with is jokes on caste and region stereotypes, corporates (especially airlines and delivery apps) and mimicry of film stars. Even these are under attack and will soon be buried under FIRs.

That is the state of affairs on freedom of speech and truth in India. Artists are self-censoring or pandering to a convenient narrative for commercial gains. And it gets worse every passing year.

Adorno wrote, “all art is an uncommitted crime.”

It breathes because it challenges power and dominant narratives. Once it moves in lockstep with the state, it loses its vitality. Because soon works of art will be created to retrofit what pleases the state. Then there’s no pursuit of any truth. It all becomes in service of the state. What remains is propaganda.

As Camus wrote in his famous essay on art, Create Dangerously (1957):

“To create today is to create dangerously. Any publication is an act, and that act exposes one to the passions of an age that forgives nothing. Hence the question is not to find out if this is or is not prejudicial to art. The question, for all those who cannot live without art and what it signifies, is merely to find out how, among the police force of so many ideologies, the strange liberty of creation is possible. It is not enough to say in this regard that art is threatened by the powers of the State. If that were true, the problem would be simple: the artist fights or capitulates. The problem is more complex, more serious too as soon as it becomes apparent that the battle is waged within the artist himself.

…Of what could art speak, indeed? If it adapts itself to what the majority of our society wants, art will be a meaningless recreation. If it blindly rejects that society, if the artist makes up his mind to take refuge in his dream, art will express nothing but a negation. In this way we shall have the production of entertainers or of formal grammarians, and in both cases, this leads to an art cut off from living reality.

…Consequently, its (art’s) only aim is to give another form to a reality that it is nevertheless forced to preserve as the source of its emotion. In this regard, we are all realistic and no one is. Art is neither complete rejection nor complete acceptance of what is. It is simultaneously rejection and acceptance, and this why it must be a perpetually renewed wrenching apart.”

India Policy Watch #2: The Tyranny of Context in Electoral Systems

Insights on domestic policy issues

— Pranay Kotasthane

In November 2022, I drew attention to the perils of the proportional representation (PR) system in the context of Israel’s elections. In the 2022 election, the vote share of the extreme right-wing party, Otzma Yehudit, doubled. And because small parties hold disproportionate leverage in PR systems, it was widely anticipated that the party would demand its pound of flesh in the government formation talks. Itamar Ben-Gvir, the leader of Otzma Yehudit, became the Minister of National Security on the back of his party's winning seven of the 120 seats in the Knesset!

Then, Oct 7 happened. The war began. When the ceasefire was announced in January 2025, Otzma Yehudit exited the government in protest. It demanded the resumption of strikes until all hostages were brought home. Given the PR system, the ruling coalition depended on Otzma Yehudit’s support to pass the annual budget, without which it could have faced dissolution. So the government agreed to its demand, Israel began another round of deadly attacks in Gaza, Otzma Yehudit was back into the ruling coalition, and Ben-Gvir was back as the Minister for National Security.

None of this suggests that the PR system is the only cause. Nevertheless, it reminds us that the PR system has drawbacks and can accentuate divisions by bolstering the fringe. We should be cautious. I’m reposting sections of my article from November 2022 explaining my scepticism towards a solution many people advocate for India.

One aspect of the Israeli political system should interest many Indians. Unlike India, Israel follows the List Proportional Representation (PR) system. This system optimises for the proportional conversion of vote share into equivalent seat share. People vote for a party, not a candidate. All parties with a vote count above a minimum threshold (3.25% currently) are sure to have their representatives in the Knesset.

India follows the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system. Voters vote for a candidate. The one who polls the most votes wins. The parties fielding the losing candidates get zero seats, even if they poll just one vote less than the winning candidate’s party in every constituency. The disproportionality between the vote share and seat share is a feature of this system, not a bug. So, a party with a 30 per cent vote share might be able to win a majority of seats and form a government.

In casual conversations about elections in India, you will come across this statement: “The root cause of unfair electoral representation is that India follows the primitive FPTP. We should instead move on to a ‘fairer’ Proportional Representation (PR) system, one in which the legislature represents the true vote shares.”

But the lived experiences of Israel’s (and earlier, Italy’s) PR system show it’s riddled with problems too. Here’s why PR is an overrated solution to India’s problems with electoral representation.

Issue 1: The Purpose of an Electoral System

A PR system can be perfectly representative and yet utterly dysfunctional. Its proponents are right that it is fairer than FPTP in translating vote shares into seat shares. By design, it will also have the positive effect of having more political parties in the legislature.

At the same time, another inescapable feature of the PR system is post-election coalition-building, in which many fringe parties hold all the aces. Israel’s recent electoral struggles are a case in point. Many smaller extremist parties are openly demanding specific ministerial posts as a precondition for their support to Netanyahu. In a democracy that is 120 times bigger than Israel, this problem of unstable and unworkable coalitions could get amplified. A government would be formed by a coalition of 20-30 parties, and the smaller partners would have disproportional leverage. Fewer governments will complete their full term. Israel has had 25 elections to the Knesset thus far, and only on nine occasions has the government completed or come closer to completing the four-year term.

Confronting the trade-off between fairness in translating vote shares to seat shares and effectiveness in creating governments that can perform is inevitable. And I’m not sure if the PR system in India can strike the right balance.

I spoke with a friend who understands India’s politics much better than I do. In his view, the fundamental goal of an electoral system is not necessarily proportional representation but to render a government legitimate. On that count, Indian governments elected using the FPTP system have been broadly accepted by the Indian electorate after the elections. The current government is testing the limits of this acceptance, but its legitimacy to govern is not under serious question yet.

Issue 2: The Party vs the Legislator

In a PR system, the legislator is virtually a rubber stamp, as candidates vote for parties, not specific candidates. The political party is at the front and centre of the system, unlike in an FPTP system where people vote for individuals to represent them.

In the Indian context, a political party is already an unhealthily powerful institution that has accreted more power through instruments such as the anti-defection law and opaque electoral bonds. Switching to a PR system would break even the modicum of connection between legislators and the electorate.

Issue 3: The Fringe as the Centre

In a divided polity such as India’s, successful political parties have no option but to cater to a broad section of the electorate to win the 30-40 per cent vote share. In a PR system, parties have no incentive to appeal to a broad section of the electorate. As long as they can win the votes of a narrow group, they are assured of seats, which would be enough to make them “king-makers”. Moreover, as the Israel experience has repeatedly shown, a PR system can legitimise small, extremist parties, a result India definitely doesn’t need at this time.

These three issues highlight that the PR system might make us worse off. Of course, this debate between PR and FPTP is not new. Some countries, such as Germany, have tried a mixed-member system in which voters cast one vote for their legislator (who has to qualify through FPTP) and another for a party list (which then translates to seats on a proportional basis). But one thing’s for sure. Every alternative is path-dependent and not without drawbacks.

The unthinking support for shifting to PR at the margins is a specific case of a general phenomenon I call the ‘tyranny of context’. The existing familiar system appears unworkable because we know its pitfalls too well. On the other hand, a reform from another country seems attractive because we don’t understand it at all.

Changing to a PR system is unlikely to result in better governance outcomes. On some parameters, it might make things worse. Ambedkar had famously warned:

“However good a Constitution may be, if those who are implementing it are not good, it will prove to be bad. However bad a Constitution may be, if those implementing it are good, it will prove to be good.”

What he said of the Constitution also seems to apply to the electoral system. It’s better to look for solutions within the constraints of the FPTP system, perhaps.

India Policy Watch #3: PLI is now ELI + TLI + CI

Insights on domestic policy issues

— Pranay Kotasthane

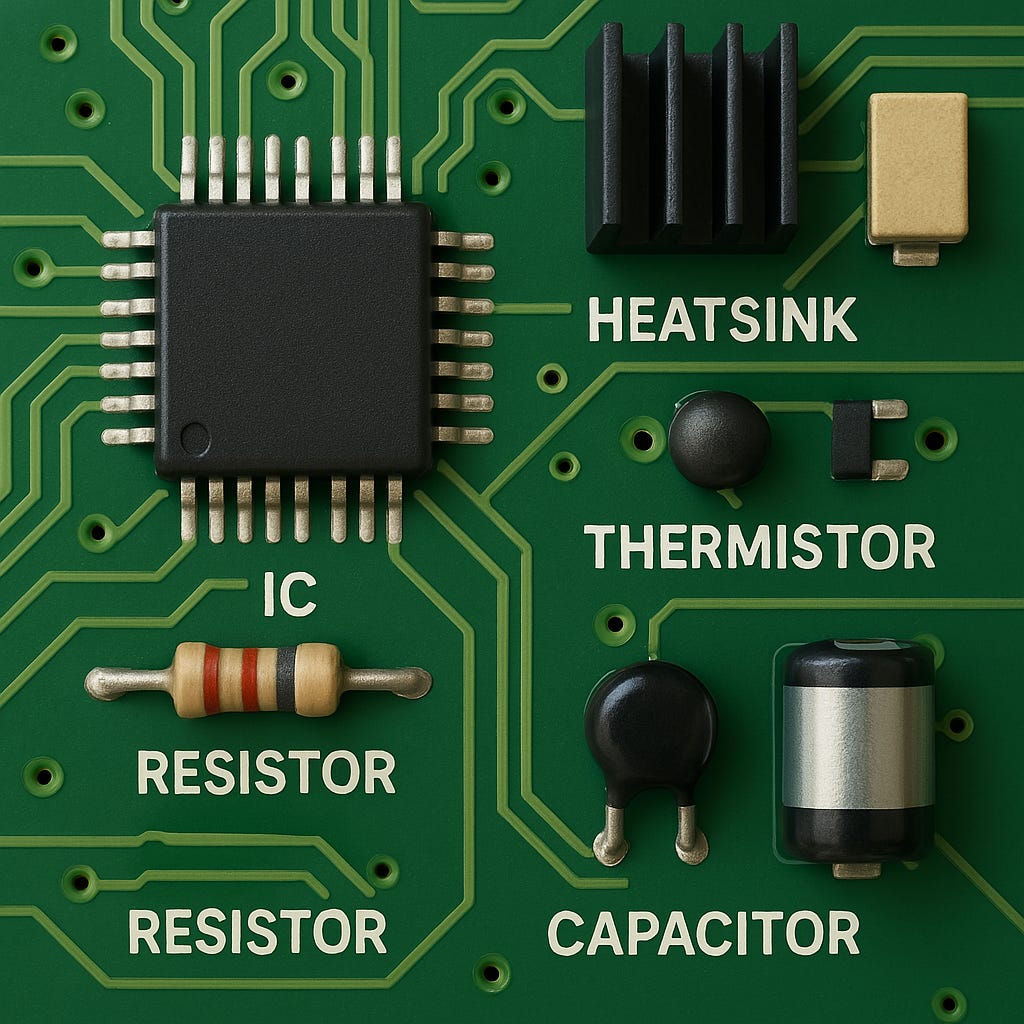

The Union Cabinet approved the Electronics Component Manufacturing Scheme (ECMS) earlier this week. The scheme incentivises the production of electronics components except chips (a different mechanism already exists for chips—the India Semiconductor Mission). This means the government is now willing to pay companies producing side-hero components like resistors, inductors, heat sinks, multi-layered printed circuit boards, etc.

What’s more interesting is the incentive mechanism. The production-linked incentive (PLI) has been replaced by something else. There are three different kinds of incentives on offer:

Turnover-linked incentive: Unlike the PLI, which rewarded incremental production within a specified period, TLI will offer payments based on the total revenue achieved from eligible products, regardless of growth or incremental changes from past performance. The aim seems to be to simplify the process for claiming incentives.

Capex incentive: Upfront capital support for buying equipment to produce these electronics components.

Hybrid incentive: this combines (1) and (2) for some of the more advanced components.

Employment-linked incentive: Finally, there’s also a line that says, “payout of a part of the incentive is linked with employment targets achievement.”

Perhaps we will have more clarity once the Gazette notification for this scheme is released. However, my first impression is that the PLI is being replaced by a policy instrument that’s hoping to achieve multiple objectives simultaneously. This is a concern because the PLI itself faced problems related to allocations—a mere 8 percent of the total PLI allocations across all schemes have been paid out thus far. Intermixing the goals of employment and turnover will likely complicate payouts further. Why not replace this complexity with a simple profit-based tax break instead?

The second point to consider is the policy goal itself. None of these components are strategic—enough alternatives exist worldwide. There is no market failure requiring government financing here. As companies start assembling phones and chips in India, an electronics component market should emerge organically. Yet, the government has announced a financial incentive, which suggests a trend—the PLI has created an expectation that the government will provide a financial incentive for every industry segment it considers essential. I’m sure companies and industry organisations have explained to the government in great detail why they cannot manufacture capacitors and resistors in India without direct support from taxpayer money.

A charitable view could be that these incentives are a necessary evil in the face of Chinese overcapacity. With Chinese exports facing headwinds elsewhere, India could see a deluge of Chinese electronics components, dissuading domestic investment. This risk is real and worth government attention. Even so, a complicated financial incentive—one that is bound to face payout problems—seems to be an ineffective way to achieve the goal. It’s time the government stops ignoring crucial pro-market reforms, such as an overall reduction in the GST rates, labour law reforms, and lowering industrial land use restrictions.

P.S.: These changes are especially relevant because whatever replaces the electronics PLI will likely be repeated in other sectors.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Yascha Mounk argues, “The idea that the country’s political dysfunction can be fixed by embracing a new electoral system is a dangerous fantasy.”

[Paper] This CSIS report on the geopolitical implications of DeepSeek and chip export controls is a fantastic read.

[Paper] A lovely little vintage paper on an overused phrase nowadays: technological sovereignty.

[Podcast] Over at Puliyabaazi, author Sohini Chattopadhyay speaks about women in sports, citizenship, nationalism, and much more. Go listen!

Great piece!

No market failure, no govt intervention. ECMS funding will come from tax payers pocket.