#307 Grasping at Straws

China's anti-India Actions, Frameworks on Tech Geopolitics, and Credit Growth Projections

Matsyanyaaya: China Gets the Jitters

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

—Pranay Kotasthane

The policy news item of this week was Foxconn recalling its Chinese engineers from its India facilities. Indian news reports cited it as another instance of China actively blocking India’s manufacturing rise. Chinese media downplayed it as a routine operational move by Foxconn rather than a geopolitical move by the party-state. Chinese media reports argued that the workload for local iPhone17 production is picking up and hence Foxconn’s decision to recall engineers.

To make sense, observe other developments over the past few months. Specialty fertiliser exports to India remain restricted over the past two months even as China has resumed exports to other countries. About eight months back came the news that China was blocking exports of Tunnel Boring Machines (TBMs) to India. These Herrenknecht TBMs were assembled in the German construction company’s China facility. And six months ago, Rest of World reported that China is actively blocking the movement of Foxconn’s Chinese employees and shipments of specialised manufacturing equipment to India. Meanwhile, the rare earth magnet restrictions on India and several other countries continue. These developments are happening even as the India-China political relationship is on the mend with the resumption of the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra after six years - a confidence-building measure suggesting a willingness to improve ties. Thus, these attempts at economic coercion seem to be out of phase.

To me, these actions suggest that China is clutching at the straws to prevent industrial capacity going abroad. They aren’t as much about blocking India’s manufacturing rise as they are about protecting China’s hitherto manufacturing dominance. Like the kid who walks away from a cricket game with his bat and ball as he senses an imminent loss, China seems to be trying to prevent the outflow of basic equipment, materials, and ideas.

But these are self-defeating moves. Neither Foxconn’s Chinese engineers, China’s speciality fertilisers, nor China-assembled TBMs are indispensable. Blocking these items doesn’t translate into significant leverage over India because they are substitutable. They might cause some delays but Taiwanese and Vietnamese engineers will easily replace Foxconn’s Chinese engineers in a few weeks. Similarly, because of Chinese restrictions, Herrenknecht India is now supplying all its Metro TBMs from their India facility. Moreover, Indian buyers will be able to source Chinese fertilisers through third countries albeit at a higher cost.

The alternative explanation for the economic coercion is that they are a response to India’s restrictions on Chinese investments and high countervailing duties on Chinese imports. This explanation appears unconvincing because China’s coercive practice is having quite the opposite effect in India. Rather than nudging India towards a workable economic relationship, these actions justify India’s concerns and actions.

What is your view about these developments? Leave us a comment.

A Framework A Week: Instruments of Technology Geopolitics

Tools for thinking about public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

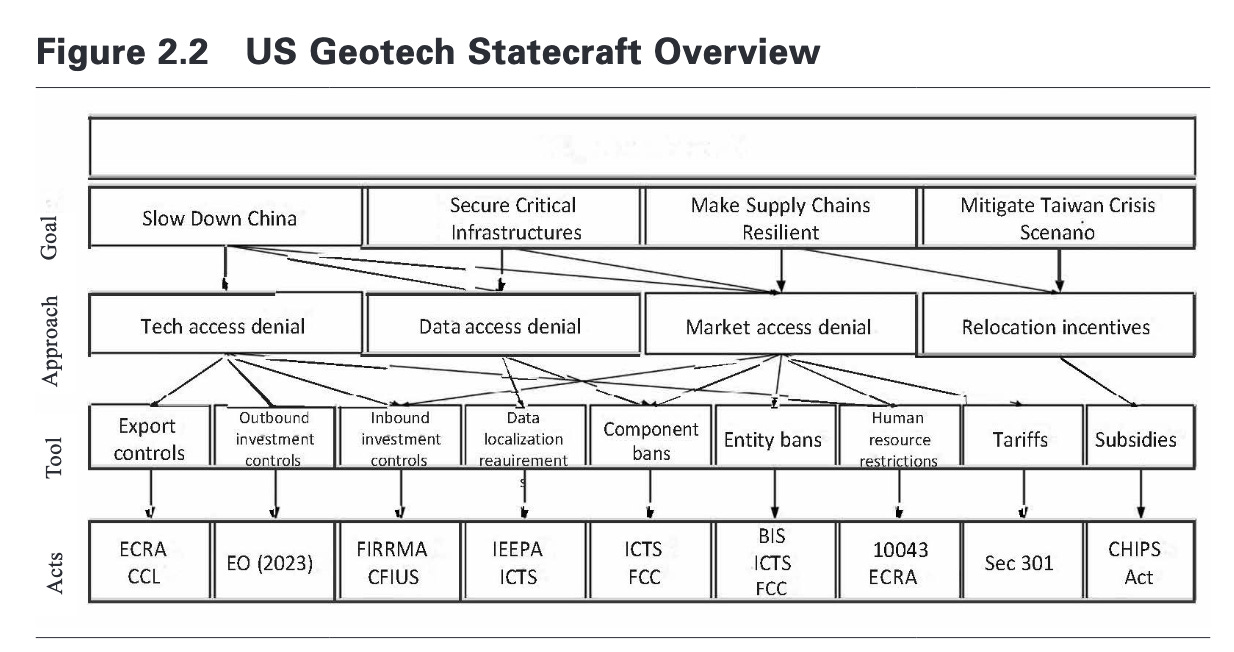

What adversarial instruments are nation-states using in the technology domain? To what ends? What are the unintended consequences of using these instruments? To think through these questions, I created this framework listing all the politico-economic instruments that we might see this decade. Many of them are already at play.

Of these instruments, the one that has fallen out of favour in recent times is “increasing dependence and control” as a way to maintain your lead over a competitor. The operative logic in this instrument was as long as an adversary is dependent on your core technology, you could control its progress and stay ahead. But as technology came to occupy the centrestage in geopolitics, this operative logic has fallen by the way. Both the US and China are trying to decouple from their competitors in select technology domains. The fallout is that with dependence on the adversary’s tech no longer possible, scientists and engineers will be forced to develop substitutes and alternatives, either alone or in conjunction with counterparts from friendlier countries.

This shift explains why a DeepSeek came about after OpenAI blocked access to Chinese users and the US government blocked Chinese users from accessing advanced chips.

China’s controls on rare earth magnets and critical minerals will very likely have the same effect. A case in point is the Quad launching a Critical Minerals Initiative earlier this week. Here’s the rationale from the Joint Statement of the Quad foreign ministers:

We are deeply concerned about the abrupt constriction and future reliability of key supply chains, specifically for critical minerals. This includes the use of non-market policies and practices for critical minerals, certain derivative products, and mineral processing technology. We underscore the importance of diversified and reliable global supply chains. Reliance on any one country for processing and refining critical minerals and derivative goods production exposes our industries to economic coercion, price manipulation, and supply chain disruptions, which further harms our economic and national security.

There are no other details about this initiative yet. And judging by the underperformance of the Quad Semiconductor Supply Chain Initiative, I wouldn’t get too excited. Nevertheless, the announcement highlights that China’s export controls is creating the imperative for alternative sources and substitute materials.

Speaking about the US and China’s tech geopolitics, a new book Tech Cold War: The Geopolitics of Technology by Ansgar Baums and Nicholas Butts is a great read on the topic. Here’s their framework on how the US and China are playing this game.

This mapping between tools and acts is helpful in understanding the many ongoing moves. The book also has good insights on how technology firms are reorienting themeselves to manage a world in which nation-states consider every technological dependence as a strategic vulnerability. Worth a read.

India Policy Watch: Waiting For Growth

Insights on current policy issues in India

—RSJ

The corporate results season in July will give an early read on how recent monetary policy actions—the 100 bps cumulative repo rate cut, the easing of risk weights on banks lending to NBFCs, and the resulting cuts to deposit rates and term deposits by banks—is playing out for consumer sentiments and private capex cycle. The question of speed and quantum of credit revival in FY 26 is key to growth projections.

The underlying thesis behind the recent monetary actions was simple. The RBI had eased liquidity post-COVID-19, and coupled with credit hunger in the unsecured loan segment, it had driven the overall credit to grow 17-18 per cent between FY 22-FY24. By late FY24, RBI could see early signs of stress in that segment as customers had overleveraged themselves with small ticket loans that were available on mobile apps of banks/NBFCs and fintechs with limited underwriting rigour. As the argument goes now, instead of only focusing on addressing the stress building in the unsecured segment, RBI launched a bazooka of measures to bring overall credit growth under control. These included raising risk weights for unsecured segments, clamping down on fintechs and co-lending models and using the relatively blunt instrument of loan-to-deposit ratio (LDR). The informal guidance to banks on keeping LDR constant or bringing it down meant that banks could only grow credit as fast as their deposit growth. For instance, the largest private sector bank brought down its LDR from more than 110 per cent to below 100 per cent in a couple of quarters. The situation was similar for other private banks, where they had to manage their LDR ratio in a tight range. What this meant was banks had to find deposit growth first before servicing credit demand. The deposit growth has been tepid over the last many quarters as household savings have declined, and there has been greater financialisation in the economy, leading to consumers participating in equity and other financial instruments rather than keeping money in bank deposits. This meant there was limited availability from customers to support deposit growth, and there was an intense battle for deposits among banks. All of this meant that the credit growth slowed every quarter in FY25 and eventually came down to about 11 per cent from the highs of 17-18 per cent. This material slowdown in credit growth also showed up in GDP growth numbers. This is the view of those who see the FY25 slowdown as purely supply-driven as the banking system tightened (or was forced to tighten by the RBI) its disbursement funnel while there was still robust customer demand. In this view, now that the supply constraints have been eased, we will see growth coming back.

I have a somewhat mixed view of this thesis on account of three reasons.

First, I think we are too sanguine about there being a robust underlying demand for credit, and that it will promptly show up the moment the supply is eased. Much of FY22-24 credit growth was driven by unsecured individual loans of lower ticket size (< ₹2 Lakh), credit cards, MSME and MFI segments. Of this, the unsecured loan and credit card growth, with the benefit of hindsight and data, was largely driven by over-leveraging by a small set of customers rather than any broad-based increase in access to credit within the economy. Customers were taking easy credit that was available because it was so convenient and there was no check on end use because it was unsecured. Much of that money went to advancing consumption or into equity markets (the simultaneous rise in small-value derivative trading volumes is no coincidence) or to other risky investment options (crypto, gaming sites, etc). If the customer demand was broad-based, we would have seen an uplift in the secured asset segments like mortgage, two and four-wheelers and durables. That wasn’t the case. The commentary of companies (producers) in these segments for most of FY25 was muted about growth, and it remains so for FY26. There is no strong underlying demand in these segments that’s lying in wait for credit to be available. The story is similar in MFI, where some easing of guidelines around how many MFI loans a group could take aided in overleveraging in that segment. This was addressed in FY25 and MFI loan growth has come off significantly. The only resilient segment is the MSME space, which will slow down a bit because of the base effect after seeing more than 20 per cent CAGR over the past four years. The thesis that FY25 was a supply-driven slowdown is correct, but the corollary to it that once supply is eased in FY26, the growth will go back to the FY22-24 range is incorrect. That growth was driven by froth in the consumer lending space, and no bank is going to go back looking for that froth.

Second, while the rates have been cut and liquidity increased, they alone won’t spur credit growth. Deposit growth continues to remain weak, and cuts in deposit rates will make it more difficult to attract term deposits. If the LDR constraint on Banks remains (implicitly), this will continue to weigh on credit growth. The liquidity will further ease in Q3 when the CRR cut comes into effect, but I remain sceptical about how much of it will show up in the deposit system during FY26. Some of these changes are structural, especially around the nature of deposits for banks (more bulk than retail) and it will take banks time to adjust to the reality of lower cost of funds and lower margins. Till then, they will try to manage their margins by keeping loan yields high.

Lastly, there is still friction in the monetary transmission of rates that will take at least a year to take shape. The rates on new loans, measured in weighted average lending rate (WALR), and the policy rates, measured in weighted average call money rate (WACR), now move in tandem faster in India than before. Almost 50 per cent of loans in the system are now externally benchmarked linked (EBLR), which reprice “automatically” when the repo rate changes, but that “automatic” part comes with a delay. This is because the nature of funding within the banking system has changed in the past 3 years, where more funding comes from term deposits, of which more than three-quarters are from tenors of more than 1 year. The decrease in marginal cost of funds (which is the “automatic’ part in repricing of EBLR) will therefore take almost a year or more before the transmission of rate cuts fully plays out.

My guess is we will see a muted FY26 on credit growth (less than 10 per cent for the first three quarters) and possibly some uptick in Q4. The underlying demand still remains the primary driver and not the supply side issues although easing there helps. The hope of seeing credit demand in the mid-teens will need consumer sentiments to change in the underlying segments.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] In the next Puliyabaazi, Garima Mohan explains trends in European foreign policy with a special focus on the India-EU relationship. Garima has excellent insights on this topic so give it a listen.

[Not(PolicyWTF)] The Union Cabinet approved the Research Development and Innovation Scheme to catalyse corporate R&D in India. The structure is promising, with the government setting up a Special Purpose Fund, which will lend to other AIFs (Alternative Investment Funds) acting as specialised intermediaries between the SPF and deep tech startups. More on this in a subsequent edition.

[Article] FT lists China’s industrial vulnerabilities - ball bearings and carbon fibres.

Rare earths gets all the headlines. But there’s a whole host of commodities that are under an informal ban.

A Switzerland based (but China linked) commodity trader I spoke to told me he could get me Cobalt hydroxide to Baltimore port but not to Nava Sheva without earning the ire of the government.