#314 It's All About the Vibes

Q1 GDP growth, India-China tango, and the Online Money Game Ban

India Policy Watch #1: Manufacturing Good Vibes?

Insights on current policy issues in India

—RSJ

Writing about the Indian economy comes with an occupational hazard. You can’t forecast a thing. I’m not talking about the medium or long term here. That’s difficult at the best of times anywhere in the world. I’m talking about the really short term. Like just a quarter. And not just predicting how the quarter would go at the start of it. The difficulty extends to predicting it even after the quarter is over. So, here we are almost two months after the end of Q1 and even a couple of days back, most analysts and research firms expected the Q1 GDP growth to come in at 6.5 - 6.7 per cent. Even the RBI had put out 6.5 per cent in its last bulletin. All the Q1 corporate results and commentary suggested a slowdown in the economy. The high-frequency indicators that act as real-world proxies indicated a slowdown across the board, barring a few exceptions like telecom and defence manufacturing. Everything from cement consumption, domestic freight movement, toll collections, power consumption, etc, was indicating that India will be fortunate to have Q1 growth at the consensus estimate of 6.7 per cent or so.

Then the data came in yesterday. Here’s the Indian Express reporting:

“Strong services sector activity helped GDP growth comfortably beat expectations for the second quarter in a row, rising to a five-quarter high of 7.8 per cent for April-June 2025, according to data released by the statistics ministry on Friday. It is more than the January-March 2025 growth rate of 7.4 per cent, and first quarter 2024-25 growth rate of 6.5 per cent.

The rapid growth in the first quarter of the current financial year further consolidates India’s position as the world’s fastest growing large economy amid a particularly turbulent time that has seen the US tariff war buffet global economic prospects and push policymakers into a tight spot. On August 27, Indian goods into the US started facing a 50 per cent tariff, with President Donald Trump having announced a doubling of the levy earlier in the month, blaming it on New Delhi’s continued purchase of Russian arms and oil.”

The nominal GDP growth rate was 8.8 per cent, the lowest in three quarters. Perhaps the deflators used have been lower. It looks like that is the case for the services sector. GDP computation for any quarter and its comparison to the previous year (where the numbers keep getting revised) has reached a level of complexity that every single estimate missing the actual number by 1 full percentage point isn’t a surprise any more. Nor is the lack of explanation between what’s seen on the ground in terms of economic indicators, being different from the GDP growth data, any longer raising eyebrows. Maybe this is the real data, and everything else is mere conjecture. What do I know? In any case, the data nicely set up the usual commentary about US tariffs not impacting India and how, after the GST rationalisation comes into play, this number will only rise despite Trump tariff shenanigans. And all of this was quite timely. Just as the PM was starting his visit to Tianjin, China, to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) meeting, where the prevailing wisdom was that India was coming in with a weak hand after being left in a lurch by Trump. With this data, India will believe it has something to offer as the world’s fastest-growing large economy. Everybody loves a good set of numbers.

Having said that, it will be interesting to see how India positions itself at the SCO summit and the nature of discussions it has with the key players there. China is a net exporter plagued by significant overcapacity (once again) and inadequate domestic consumption. It is difficult to imagine China as a market for any Indian exporter looking to diversify away from the U.S. market. Russia, the other big player in attendance, is a relatively smaller market already dominated in key sectors by Chinese firms. The remaining players attending this are either smaller markets who themselves are impacted by Trump tariffs (Indonesia, Central Asian republics, etc) or those with whom India won’t be keen to trade (Pakistan, Turkey). So, there isn’t a lot at stake on the trade front here. A revival of trade ties with China is a good move regardless. This is a point we have made all along that trade with China will be a net positive for India so long as we keep strategic sectors out and ensure data localisation norms are followed. There isn’t a possibility of a deeper or strategic relationship with China at this moment given Pakistan and public perception of China in India. The political point of cosying up to China and Russia and inducing the saner minds in the U.S. to question the Trump administration on the logic of alienating India to such an extent remains moot. Almost a month since Trump went rogue on India, I see the visible pushback to pick on India quite limited going by what’s appeared on media so far. A few thinktanks have made some noise and there’s been some general lamenting of mistreating democratic allies. If there was a focused strategy over the past two decades to keep India on its side as a counter to China, it is not clear how deep that commitment was within the Washington policy circles based on evidence so far. On balance, it kind of proves that at its current size and capability, India isn’t material to US interests. It doesn’t lose sleep over what India thinks of it. In fact, the likes of Bessent and Navarro have gone on an offensive, accusing India of profiteering, being an “oil money laundromat” and more, while simultaneously treating China, guiltier than India on these counts, with kid gloves. Maybe the Indian calculus is that a more visible alignment with China and Russia will trigger more introspection on what the U.S. is losing in the bargain. I’m sceptical of it happening with this mad as a hatter administration that prioritises transactional benefits over strategic collaboration. It might only get them madder and make it worse for India. After all, it takes only one deranged post from Trump on hurting India’s service exports to the U.S. to queer the pitch here. In any case, my sense is that India has decided it doesn’t mind a few quarters of trade impact before it seeks rapprochement with Trump. During this time if it could find other export markets for its suppliers through quick bilateral deals, or its exporters figure out a way to go around the tariffs, or the front loading of exports before the tariffs came into play sustains them for some time, then India will hold on to its growth projections for FY26 and prove its resilience to the U.S. It could then deal with Trump with somewhat of a better hand than now. This scenario of hunkering down and waiting for the storm to blow over is quite realistic and looks like India’s best bet at the moment. Therefore, I don’t see any significant movement on trade talks before the end of the year. Neither party is keen now to move the puck forward.

Separately, a US appeals court on Friday upheld a decision by the US Court of International Trade in May that ruled that Trump did not have the authority to use emergency legislation to impose global tariffs that he imposed on Liberation Day without the explicit consent of Congress. In a 7-4 verdict, the appeals court wrote that there was no discernible authorisation for Trump to use specious justifications like fentanyl import or national security to impose tariffs on countries like Canada, China or Mexico. I’m somewhat surprised that the appeals court still has the spine to rule in this manner in times like these, when Trump has taken a leaf out of the Indian political playbook and set the FBI or IRS to harass his opponents or dismissed Fed officials on his whim. Just to get better at this kind of skulduggery, Trump should have better relations with India. The Indian political class has a lot to teach him on this count. In any case, the appeals court gave the Trump administration till October 14 to put this ruling into effect so that it can appeal to the Supreme Court against this verdict. It will be a huge surprise to me if the Supreme Court doesn’t reverse the appeals court ruling and restore the decision-making authority back in the hands of the President. But the appeals court’s decision was still a useful reminder that it will take more than this Trump term and a sustained concerted effort to run US institutions to the ground. Not that they aren’t trying their best to do so. But there’s hope that some kind of order will be restored eventually.

Matsyanyaaya: Making Sense of the India-China Thaw

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

—Pranay Kotasthane

The Indian PM is in China for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Meet this week. You will come across many articles that amplify how India and China are executing a ‘strategic reset’ in response to Trump’s tantrums. Even in the lead-up to the meeting, the perception in the Indian and foreign media is that India has suddenly swung towards China; that the QUAD will cease to exist; and that BRICS, RIC, and SCO will become super vital from an Indian lens.

But that would be a wrong conclusion.

First, we must acknowledge that many knots in the India-China relationship have been undone thanks to the Trump administration's actions against India. It's foolish to argue that these things would have happened anyway. Recent reports in the Indian media suggest that the relationship status change was underway regardless of Trump. Hence, we now hear of ‘a secret letter’ Xi Jinping sent to the Indian President in March expressing interest in better ties with India. The fact that India started showing interest in this outreach only after the Trump tantrums began, and that this news has come out only now, suggests that the US administration is the catalyst in the India-China reaction.

But this doesn't mean India favours ditching the US for China. The India-China relationship is currently a transactional trade relationship and nothing else. India does far fewer things with China than China does with the US, Japan, and Australia. For example, the bilateral trade figures for all three countries with China far exceed the India-China trade figures. At present, there isn't even a direct flight between the world's two biggest countries. There are no significant people-to-people connections, and the reciprocal public opinion of the other nation-state is mainly negative. Even the US under the Biden administration did far more with China than India did with China.

Further, investments from China face severe restrictions in India; the Great Firewall prevents Indian software firms from accessing the Chinese market, India-China border issues continue to fester, and China's relationship with Pakistan will always limit the kinds of things India and China can do together. None of these issues can be resolved easily.

Given the relationship's low base, it's easy to mistake new engagements for some kind of strategic reset. But they really aren't anything like it. There are structural barriers to the India-China relationship and structural enablers for the India-US relationship. It's up to the US administration to decide where it lies with respect to China. India, for its part, will continue to resist China's aggression in its own way and now collaborate lightly in a few economic domains.

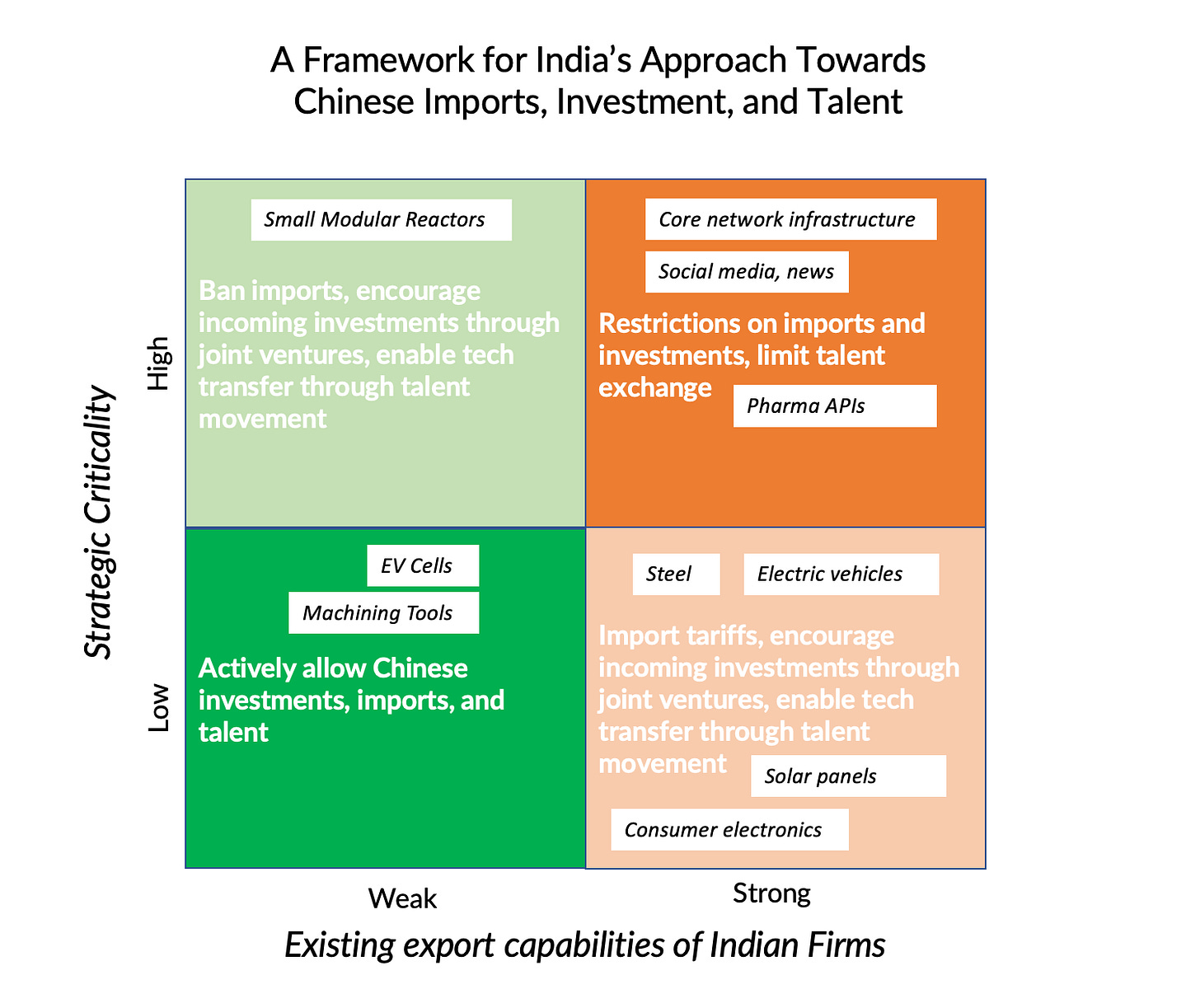

Keeping this context in mind, here are some new developments on the India-China front. A report in Mint claims "India has identified manufacturing, renewable energy & auto components for relaxing covid-era curbs on Chinese investments.. it's considering a plan to allow 20-25% Chinese investments in these sectors through the automatic route.” This is a much-needed normalisation in the economic relationship. We have consistently argued that India should welcome Chinese investment for our benefit. In July 2023, I had argued that:

the Indian government needs to make two shifts in its policy approach to China.

One, distinguish between the Chinese government and Chinese businesses. Indeed, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) controlled economy means that Chinese businesses have less agency than their counterparts in the US or India. It is also true that China’s aggression on the border and adversarial positions at multinational fora show that it sees a growing India as a threat, not an opportunity. However, it is also important to note that Chinese businesses—especially suppliers to other multinationals—have different incentives than the CCP. Outside a narrowly defined set of strategic sectors such as defence and telecommunications equipment, investments by such businesses in India is a net positive.

Chinese investments can also give India foreign policy leverage. Economist Swaminathan Aiyar’s recommendation that “massive foreign investment is a bigger risk for the foreigner than the investee country. So, let us attract as much Chinese investment as possible, since the main risk will be theirs, not ours,” needs deeper deliberation beyond simplistic binaries.

Two, the Indian strategic establishment needs a sharper definition of what constitutes ‘strategic.’ It is insufficient and counterproductive to define entire sectors as strategic. Not all types of chips or LCDs are strategic. Dependence on China for these items does not make it a strategic vulnerability for India.

China’s success in manufacturing was possible because it was willing to harness Western investments despite political and ideological differences. Though the India-China relationship remains complicated due to simmering tensions along their shared border, India must take a leaf out of China’s book and cautiously utilise Chinese products, investments, and talent to close the power gap.

If taken forward, this would be a positive step from an Indian perspective. Again, such a move doesn’t mean India has swung towards China. The US, for instance, has a far more liberal stance towards incoming Chinese investments in non-critical sectors than India. By allowing a predictable investment environment, India would only be taking a position that makes economic and tactical sense.

The other news item of the week was that India plans to lift its 2020 ban on all Chinese apps. The opening of two positions in TikTok India’s Gurgaon office further fuelled this story. The government, however, responded that its position on this issue had not changed.

Since India’s ban, TikTok has headquartered itself in Los Angeles and Singapore to distance itself from its parent Chinese company, ByteDance. But we also know now that TikTok has been used as a weapon of cognitive warfare in Taiwan. Thus, it makes ample sense to be cautious about any Chinese product with cognitive autonomy implications.

Perhaps our framework from edition #267 still holds good.

India Policy Watch #2: Game Over

Insights on current policy issues in India

—Pranay Kotasthane

Earlier this week, an online money gaming firm filed a case in the Karnataka High Court challenging the Promotion and Regulation of Online Gaming Law, 2025. This law prohibits online money games such as Poker, Rummy, fantasy sports teams, and prediction markets. It also seeks to promote e-sports and online social games, i.e., games that do not involve staking money in the hope of receiving a larger sum. For context, the online real money segment constitutes nearly 86 per cent of the total online gaming sector revenue.

The stated intentions of the ban are that many people have lost money while playing these addictive games, which are aggressively marketed by celebrities and influencers; and that online money games promote ‘financial fraud, money-laundering, tax evasion, and in some cases, the financing of terrorism’.

In other words, the regulation does not address issues like excess screen time, child protection, or cognitive autonomy but is specifically targeted against financial consequences.

Let’s look at the restrictions in other countries to get a fair idea of the regulatory landscape.

Australia has maintained a strict ban on online real-money games like casinos and poker since 2001 under its Interactive Gambling Act. But this ban exists alongside a rampant offline gambling scene, with poker machines ("pokies") common in pubs and clubs. This dichotomy has fuelled criticism that the law protects the revenues of powerful physical gambling lobbies while driving determined online users toward riskier, unregulated offshore platforms.

The US offers a different model, one of regulated permission. Following a recent Supreme Court decision, the power to legalise sports betting was returned to individual states, resulting in a patchwork of regulations. Most states have legalised online sports betting, and a smaller number have also legalised online casino games. The treatment of games like poker and rummy varies, with many states regulating them as skill-based games or under specific casino licenses.

China presents the most prohibitive model of all. It prohibits all forms of online gambling and real-money games. The only exceptions are two state-run lotteries. The enforcement is severe, backed by criminal penalties and the Great Firewall designed to block access to foreign gambling sites. However, even China’s approach has a release valve: Macau and Hong Kong operate under entirely different legal frameworks where these games are allowed.

As this global experience reaffirms, there is no doubt that this segment requires government intervention. But a ban seems excessive and disproportionate for three reasons.

First, a philosophical point. It grants excessive coercive power to the state. A government that takes upon itself the role of protecting citizens from their own financial missteps in gaming will also be expected to provide people with quotas, electric appliances, LLM access, and jobs. This Maai-Baap Sarkaar logic has no clear endpoint and will continue to erode personal responsibility and freedom of choice.

Second, the practical utility of the ban is highly questionable. The notion that banning these games will drive people toward more virtuous behaviours is weak. While those on the margin might indeed migrate to e-sports, the determined player will not be stopped. They will simply seek out options using VPNs and offshore, unregulated websites. Players will be exposed to platforms with no consumer protections, no oversight, and a far higher risk of fraud and manipulation. The most determined might even pivot to something far more dangerous in the completely unregulated underground.

Finally, better options exist. Just as the stock market has circuit breakers, constant risk disclosures, and strict regulations on advertising and selling, online real-money skill games could have been subject to similar robust controls. A regulatory body could have mandated strong KYC norms, implemented mandatory deposit limits, and created a national self-exclusion registry (like Australia). This would have directly addressed the state’s concerns about addiction and financial security without resorting to a prohibition that pushes it into the shadows.

What do you think?

P.S.: I’ve intentionally avoided the ‘game of skill vs game of chance’ differentiation because I always found that distinction self-serving and specious. I also find the arguments about the lost tax potential erroneous. Government revenue potential should never be the first reason for judging a sector.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] This Puliyabaazi is a deep-dive into the street dogs mangement issue.

[Thread] SemiconIndia 2025 will take place next week. This X thread is a ready reckoner on all the major developments since December 2021, when the new set of semiconductor policies was announced.

[Article] Sandeep Bhardwaj explains the Super 301 episode in this Times of India piece, when the US unsuccessfully put tariffs on India in 1989 with the intention of opening up the Indian economy by force. That didn’t work (Hum Nahin Sudhrenge), but India did take up serious reforms by 1991. Let’s see what happens this time around.

[Journal Issue] The next edition of the Indian Public Policy Review journal is up. It has excellent long-form policy perspectives. Read, share, and subscribe to get an update once every two months.

Agree the ban feels more like virtue signaling (like the plastic straws ban) rather than a well thought policy. I expect folks who are 'sold' on RMG as a way of making money, as something they're happy to do anyhow etc to go underground or worse migrate to overseas platforms that offer RMG. A side effect will be crypto wallets usage.

This surprising ban on a business overnight seems very bad. It reduces government's credibility and takes confidence out of honest business people.