#32 The Indian State Walks Into a Bar...

Morality around alcohol consumption, India and post COVID-19 world order, and stock market divergence

This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PolicyWTF: Alcohol, Morality and the State

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

The Bechdel test is a non-scientific measure of gender inequality in fiction and films. The test is simple. A work (book or film) passes the test if it has two named women characters speaking to each other about something other than a man. About half the mainstream films in Hollywood fail the test.

I have devised the Indian equivalent of the Bechdel test. It is a test to measure our attitude towards alcohol. A Hindi film passes the test if it has two or more characters drinking without:

Anyone nursing a heartbreak

Planning or doing something illegal

Singing or dancing

Modestly, I call it the Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley (RSJ) test. My rudimentary analysis shows less than 1% of Hindi films qualify the RSJ test. Apparently, our society can’t ever imagine ordinary people having a drink responsibly. If you have examples, I would like to hear from you.

Anyway, that brings me to the three truths not universally acknowledged about alcohol in India.

First, we drink a fair bit. India consumes about 8-9 billion litres of alcohol every year (not accounting for arrack or local toddy). That’s 6.5 litres per person per annum. We have over 180 million people who drink regularly (tipplers as the media delights in calling them). The industry has been growing between 8-10 per cent annually over the last decade. If Hindi films are to go by, we should be having a whole lot of singing, dancing and crimes every week on our streets. But we don’t. Most people drink responsibly and get on with their lives.

Second, governments earn a lot from alcohol. The industry is among the top revenue contributors for most states. The states collect more than Rs. 1.5 lakh crores in excise alone every year. If you add sales tax, commercial tax, and various cess, this number would easily double.

Third, the policies regulating alcohol in India continue to draw their moral inspiration from Hindi films. They are steeped in misplaced morality and they vary across states with bewildering complexity. Every aspect of the value chain is controlled – production, distribution, pricing, taxation, consumption – with an infinite variety of laws across states.

A study by Pahle India Foundation (p 69) found a manufacturer needs about 10,900 (!) certificates or licenses from various agencies to operate a plant in Maharashtra. The Pahle India report (p 69-83) on ease of doing business in this sector isn’t meant for the faint-hearted. You might need to fortify yourself with a peg or two before you dive into the byzantine maze of regulations. There was also a time when you needed a permit to drink in many states (the origin of the term ‘permit rooms’ for establishments selling alcohol). There’s arbitrariness, rent-seeking and inefficiency in regulating the industry.

Now, if anyone had paused to think about these obvious truths at the time lockdown was announced, they would have reached a simple conclusion. People will want to drink, and the states will need alcohol-related revenues during the lockdown.

The solution to home deliver alcohol was obvious and was suggested by many at the start of the lockdown. Instead, 40 days later, the state starved of funds had to reopen alcohol outlets (even in red zones) and we had people queuing up with little or no consideration for social distancing guidelines. After almost a week of chaos, a few states have since decided to sell it online. But not without further use of arbitrary powers. Most of them have added a ‘corona tax’ ranging anywhere between 20-70 per cent. There will, of course, be unintended consequences. The demand for alcohol might not be as inelastic. The overall revenues might actually fall. With purchasing power dwindling for people across the board, cheaper and illegal substitutes will find takers. Expect ‘hooch’ tragedies to make a comeback in news. An artificially high price will create conditions for a thriving black market. In all likelihood, neither the state nor the society will benefit. Yet, the states seem to be in a race to implement such ill-considered policies.

In ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments’ (1759), Adam Smith showed our moral ideas are the product of our nature as social creatures. Morality is part of our very nature and benefits us and society. We have in-built moral standards to guide us. The state shouldn’t concern about the morality of its citizens. It should focus on rules of justice to protect individuals from harming one another. In its regulation of alcohol, the Indian state does just the opposite. It uses significant state capacity to police the morality of its people while being lax on rules of justice.

The results are obvious – an inefficient alcohol industry and warped social attitudes towards alcohol. The costs are enormous.

A Framework a Week: India and the Post COVID-19 World Order

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

I’ve discussed our New World Order Framework here before. This week, we (Akshay, Anirudh, Anupam, & I) came out with a research publication that applies this framework to answer these questions:

how the world order might change due to the COVID-19 pandemic,

how this changed world will affect India,

the domestic policy reforms needed to prosper in this world,

Geopolitical pathways for India in this world, &

Small bets that may hold it in good stead under uncertainty.

For us, world order scenarios are at the intersection of geoeconomic trends on one axis and geopolitical trends on the other one. Using this framework, let’s look at where the world is possibly headed after COVID-19.

On the geopolitical side, both superpowers face a decline in absolute power. Middle powers have more leverage. Smaller powers need capital, regardless of where it comes from.

On the geoeconomic side, we are headed towards a global recession in the short run, perhaps secular stagnation in the medium-term. Liberal economic order is under threat and economic nationalism is back in fashion.

We call this scenario “Race to the Bottom” world. It was one of the 20 world order scenarios we imagined in 2017.

How does this world look like in the backdrop of COVID-19? One, we are moving from one to many economic webs. One led by the US dollar, the other by China's capital, and a more diffused collection of middle powers who independently strike bargains with the US and China.

Alright, alright.. how does this order affect India, you ask? Much depends on how India responds to the pandemic and what welfare and healthcare systems will be put into place in the coming years. Rebuilding broken social harmony will be a key imperative for building strength.

Besides that, In a “Race to the Bottom” world, global labour flows will become restricted. Capital flows are likely to thin out. India needs another engine of growth in such a world. Large-scale manufacturing offers one such opportunity.

Specifically, on the foreign policy outlook, there are some actions India must take regardless of what the rest of the world does:

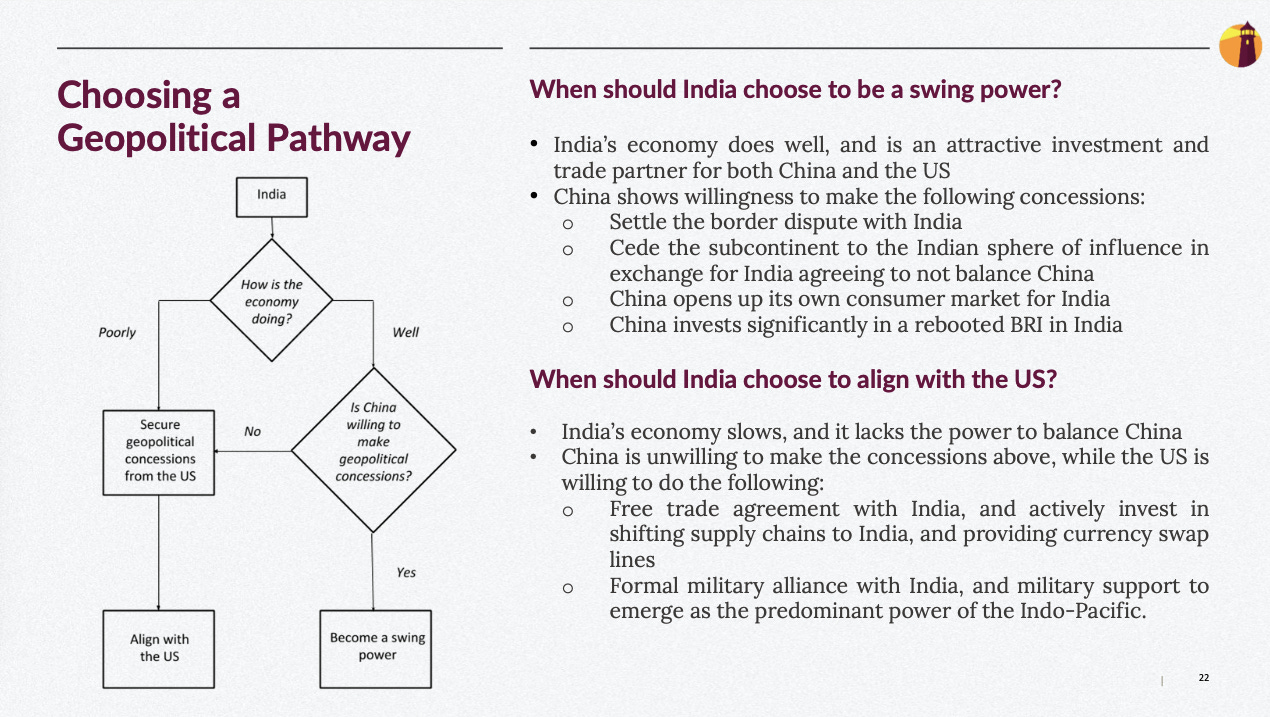

Leaving these 'dominant strategy' moves aside, two potential geopolitical stances for India in the new world are one, to be a swing power for both the US and China-led groupings & two, to "align" itself more closely with the US. Here's a flowchart to help think about this.

Given how uncertain this world is, India should also invest in small bets, which when doubled down on, could yield big benefits.

There’s more to this. The entire document can be read here. It’s intentionally not written in an academic paper format. Do read and let us know what you think.

India Policy Watch: The Perils of a Badly Directed Stimulus

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

The NASDAQ Composite was at 8464 about 6 months back. Six months, over 1.3 million COVID-19 infections and 75,000 deaths, $3 trillion of stimulus and a record 20 million job losses later, the NASDAQ Composite is at 9121. It is up 7.8 per cent. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had its best April in 33 years after it rallied up by about 11 per cent. In India, the Nifty 50 was up 14 per cent in April while conservative estimates suggest the lockdown might have cost us between 8-10 per cent of output, about 110 million jobs and maybe, a third of our MSMEs.

The divergence between stock markets and the main street hasn’t been starker.

The general theory about a market index is it reflects the present value of future earnings of all stocks based on existing information. Since the stocks that make up the index usually represent different sectors, the index is assumed to stand in for the whole economy. As new information comes in, the index moves up or down depending on how it views it. With that in view, it would take some serious stretching of credulity to believe the information we’ve been getting over the past month is good for the economy. But that’s what the index shows.

Wall Street versus Main Street

The market participants have their reasons for this. The oft-repeated view is the market is solely focused on the future after pricing in all existing information. So, all bad news of 2020 is factored in and the market is already looking beyond it. The other view is that market tends to overreact on either side. Examples from the past are given to support this. For instance, between 2007-09, the real GDP in the U.S. contracted only by about 4.5 per cent while the index fell by half. Lastly, with interest rates at near zero, there’s a view that surplus capital has nowhere to go except to the markets. Well, these aren’t entirely satisfactory explanations.

A more specific view of the markets will perhaps help. The index only represents the views of the owners of stocks about their own future. Not that of the broader economy. The $3 trillion stimulus by Fed with its bailouts for various industries, buying of junk-rated corporate securities and helping out of large and small corporates by lending to them directly is seen by market participants to largely benefit only them. It is no surprise that almost everyone linked to markets has praised the speed with which the Fed acted this time compared to GFC.

By linking the stock market performance to Fed’s actions, the market has deftly trapped the Fed into the responsibility for holding up the index. Separately, the prices for Fed funds futures contracts for early 2021 already suggest it will take the policy interest rate below zero. These are self-fulfilling prophecies. The Fed has already shown its hand by proclaiming its ‘whatever is necessary’ to support the economy. The capital markets, aided by a President who sees the index as the real measure of economic health, have captured the Fed’s policy response. The market, therefore, isn’t looking at the carnage unfolding in the real economy at this moment. They are betting on the Fed making good whatever losses they incur till things get back to normal. This will lead to a huge debt burden for the future generation. But the way the deck is stacked, it will be carried disproportionately by the same class who are carrying the burden today.

Intervening for wrong reasons

There were easier options to hold up the pandemic economy in the US. The workers on payroll could have been supported by using the IRS mechanism in reverse to deposit funds into their bank accounts. The existing bankruptcy procedure was fair and robust enough to manage the balance sheet restructuring for most large corporates where the creditors got preference over equity interests. A separate relief package for small businesses for a short period of time would have helped those who truly needed support when liquidity dried up. These would have cost a fraction of the trillions that have been spent while letting markets do what they do best - allocating resources efficiently and rebuilding for future.

The coordinated actions of the U.S. government and the Fed that began during the GFC continue to distort the markets. The temporary relief these actions bring while kicking the proverbial can down the road shouldn’t blind us to their reality. These policy actions should be judged by their results that protect a minority of fund managers, investors and shareholders. This kind of repeated insidious interventions will have extreme economic consequences in future. The Indian indices so far have mirrored the U.S. markets with the hope of a similar stimulus package. That we too need a relief & reconstruction package is beyond debate. We will do well, however, to avoid walking down the same path in designing our stimulus.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] In his Business Standard column ‘The inevitability of classical economics’, TCA Srinivasa-Raghavan argues the state has reached its limit for both Marxian and Keynesian interventions and it’s time for Fisher, Hayek and classical economics

[Article] Gunjan Banerji in the Wall Street Journal offers five reasons why the market is rallying when the economy is so bad

[Paper] Pritchett, Woolcock, and Andrews’ classic paper on implementation failures

That’s all for the week. If you like this newsletter, please do share.