#50 Sunday Double Bill: Ab Tak Chappal & Close Encounters of The Third Kind

A perfect encounter, crime in politics, retributivism, the hawai chappal tax structure, VCs versus media elites, trade policy as a means of coercion and more

This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

India Policy Watch 1: The Chimera Of A Just State

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

Vikas Dubey, a dreaded gangster with multiple cases of murder against him, was killed in a police ‘encounter’ on Friday morning. In the past week, five of his associates who were involved in gunning down eight policemen were killed in different encounters or while they were in custody.

The Perfect Encounter

Dubey was arrested on Thursday at Ujjain. On the way to Kanpur in police custody, their vehicle overturned. Then Dubey did things that confirmed his legend. In that overturned van, he freed himself from his handcuffs (Houdini). He snatched a service revolver and shot out of the van defying gravity (Iron Man). He then ran some distance despite having a steel rod in his leg that gave him a limp (Forrest Gump). After a while he remembered he had gun that could be used to shoot at the police (Gulshan ‘bad man’ Grover). Instead he was shot dead. While displaying such daredevilry, he kept his mask on. Guns didn’t scare him. Virus did.

As far as subliminal messages on the danger of COVID-19 go, this can’t be surpassed.

The police claimed the vehicle turned over because the ‘tired’ driver tried swerved away to save a herd of cows. God bless him. Running over a cow could possibly have meant a different headline. Anyway, I remain in hope we will soon hear the transmission system of that vertiginous vehicle was made in China. That will make it a perfect encounter.

Encounter killings aren’t new in India. Yet this week was remarkable. Almost everyone predicted Dubey and his associates will be killed in encounters. And we counted them down while the police filled us with stories of the encounters. The public response to the killings has been unsurprising. The ‘nationalists’ view these as a form of speedy justice that the due process of law won’t guarantee. Their argument is these gangsters deserved what they got. So, what’s to complain? The ‘liberals’ are aghast at the vigilantism of the state. This is a slippery slope, they warn. And then there are those who wonder what dark secrets about the establishment did Dubey and his gang carry with them to their graves.

This sordid saga can be looked at from multiple perspectives. We are interested in two. First, the nature of the relationship between criminals and politicians in India. How do we understand it?

Second, the increasing allure of retributive justice in our society. What confers legitimacy to retributive justice and what are its constraints?

1. A Theory For Criminals In Politics

Let’s paint a picture of the Indian state in broad strokes. Like all states, it has a legitimate monopoly over violence, and it uses it to manage law and order, among other things. India is a poor country and for most of its citizens the state is also the ultimate provider of resources and services. The Indian state is large in its remit and in its ambition but ineffective in translating them to actions. On paper it has a lot of responsibilities but in reality it doesn’t have resources to discharge them.

There are three kinds of state behaviour that sets the ground for criminality.

One, the absence of the state. This is quite common in India where the state has low capacity but high ambition. In many interior parts of India, the state can’t fulfil its responsibility of providing law and order. Also, its role as the ultimate provider of resources and services is compromised by vested groups who coral them. In the absence of the state, a local enforcer takes over. This enforcer represents the interests of specific dominant group (mostly a caste), captures the resources of the state and becomes the quasi-state in the region. But this capture of the state is not without ‘contestation’ from other groups. This leads to a cycle of crimes resulting in consolidation of power or a fragile peace between the groups.

The politicians find these enforcers useful because they hold sway over voting blocs. In a ‘first past the post’ electoral system with multiple parties in fray where a 30-35 per cent vote share is adequate to win a seat, these enforcers can swing the elections. In the 80s as the hegemony of the Congress weakened, many enforcers cut out the middleman (politician) and jumped into the electoral fray. The growth in Indian economy meant they got richer by capturing government contracts and branching out to other businesses. Over time they had money, muscle power and their loyal caste base – an unbeatable electoral combination.

This model has been replicated across India with minor differences. In regions where Indian state has been able to make deeper inroads, the enforcer has become less a criminal and more a businessman. This applies to the more prosperous states in southern and western India. In the Hindi heartland, it is still the wild west.

Two, the unwarranted interventions of the state with unintended consequences. Think prohibition, bad real estate or tenancy laws, high import tariffs, misclassification of resources like water and coal as public goods and more. Each of these leads to the emergence of powerful mafia that helps citizens circumvent these bad laws. The list of liquor dons, smugglers, water or coal mafia and real estate goons is long in Indian cities. Since corporate political funding in India was banned for a long time, these criminals funded politicians in return for patronage. Over time, they morphed themselves into businessmen and joined political parties.

Three, the absolutist state. This is where the citizens have allowed the state to have unlimited power over them on ideological grounds. The ideology could be political, religious or something contrived. The agents of the state have a free run and often turn into criminals. This is the worst form of criminality in politics. Barring a couple of years of emergency, India has not seen absolute state control. But there is a divide that’s emerging where every issue is seen through a partisan political lens. The priority in framing any narrative is not the merits of a position but how it will help strengthen a political ideology or the other. The debate on the killing of Dubey is an example of this framing. Turkey, Hungary, Philippines and Brazil have seen more egregious versions of this play out in their polity. The institutional strengths of these countries have been no match to this capture. US and UK are in the midst of this battle where the civil society is holding out. We should keep an eye out for any ideological capture.

A Looming Threat

The Indian state brought criminality in politics upon itself through its absence or injudicious interventions. The saga of Dubey’s rise and his death is another instance of this. The solution to this is in narrowing the scope of the state and making it stronger and effective within that. But we aren’t heading towards that solution. The consensus being manufactured justifying Dubey’s extra-judicial killing and the ease with which it is being accepted by people portends the start of the third kind of criminality. We will have agents of the state turning criminals because they have absolute power and the moral sanction of the public. This is dangerous. History has shown it singes everyone. The guilty and the innocent.

This shouldn’t go unchallenged.

2. Retribution Is Not Revenge

There’s an intuitive appeal to the notion of retributive justice. Someone commits a crime. They inflict pain on others without their consent. So, they need to be punished. This is easy to understand. There are philosophical disagreements over this though. There are other theories of punishment that focus on deterrence or incapacitation. But they have moral problems in them too. For instance, deterrence justifies using people as means for a larger good. This is the notion of punishing someone to set an example to others. This goes against Kantian categorical imperative or the supreme principle of morality. Others find retributive justice puzzling. H.L.A. Hart, the famous British legal philosopher, once termed it as a ‘mysterious piece of moral alchemy in which the combination of two evils of moral wickedness and suffering are transmuted into good.’

Kant believed the law of retribution or jus talionis is the only way to determine the appropriate degree of punishment. The three claims of jus talionis are:

Punishment is justified only if it is deserved

It is deserved only if the person has voluntarily done a wrong (that which is being punished)

The severity of punishment is proportionate to the severity of wrongdoing

Among the most convincing arguments made in favour of retributive justice was Herbert Morris’ appeal to fairness. Morris states that for us to live in a society and derive benefits from it, we must accept certain limits on our behaviour. If a person fails to exercise this restraint, he abandons a burden of constraint that others have taken upon themselves. In this way, he gains an ‘unfair’ advantage that others don’t have. This advantage must be squared through a punishment.

The two questions that follow then are – who should be the punisher and what should be the quantum of punishment?

The State As The Punisher

In the state of nature, the victim should be punishing the wrongdoer. This has many problems. The criminal might not be accessible to the victim to inflict punishment. Not all victims may also be in a position to punish. This world is matsyanyaaya, your ability to punish the wrongdoer is circumscribed by your relative power.

This is where the state steps in. Max Weber defined the state as a human community that successfully claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. Simply put, people transfer their right to the use of physical force to the state to earn justice. The state build institutions to use this legitimate force. The institutions include the parliament to draft laws, the judiciary to determine guilt and the police to enforce law. These institutions provide the victim with the access to the wrongdoer, to argue for their punishment and the courts decide on the quantum of punishment based on precedence, written laws and jurisprudence.

The severity of punishment should be proportional to the gravity of the wrong. The gravity of wrong can be tempered by factors like intentions, first-time offence, extenuating circumstances or background. The scale of punishment is set with a few cardinal bands marked for certain kind of crimes and then building an ordinal proportional scale between them. The state sets these laws.

The Fault In Our Encounters

Now, let’s view the reactions to encounter killings from this perspective.

The citizens of India have transferred their right to use physical force to the state. This is important for people who argue – what about the rights of those eight policemen killed? The state has all the powers, physical and moral, to exact retributive justice. The system is designed for this. The state as a punisher has defined the norms for the use of this force to ensure it doesn’t turn into a predator. This protects the ordinary, innocent citizens from the unbridled power of the state. These norms include the process for framing of charges, identifying the accessaries, proving guilt and delivering punishment. The state doesn’t have any right to pick and choose among these responsibilities. Any compromise in this chain of checks and balances runs the risk of the state inflicting violence on the innocent. The encounter killings are acts of bad faith by the state because they violate this.

The institutions of the state work in tandem to deliver retributive justice. One arm of state can’t blame another for laxity and strike out on their own. So, the police can’t implicitly blame the judiciary for delays in delivering justice. The failure is collective. In any case, judicial delays aren’t the reasons why criminals like Dubey weren’t behind bars. We have seen the state keep people in detention for long when it has so desired. The state has to find solutions to its problems. The state can’t externalise its failures and plead its hands are tied.

Retributive justice of the state is important to curb vigilantism in society. In its absence, vigilante groups would deliver justice without following any checks and disproportionate to the quantum of offence. When the state abandons due process, it becomes a private vigilante group exacting revenge. This can trigger a cycle of retribution and encourage vigilantism among other private groups. There’s also the risk of criminals escalating violence against the state because there’s a huge ‘dis-incentive’ to surrendering to the state. This will lead to more lawlessness in society hurting ordinary citizens.

Know The Difference

The ‘celebration’ of encounter killings by sections of society and the media lets the state get away with its failures to deliver justice. The multiple holes in the story of the police suggest the state isn’t even making a pretense now to hide its failures. In a perverse way, it has turned this failure into its success by playing to the gallery. Retributive justice shouldn’t turn into revenge orchestrated by the state. The long-term repercussions of this kind of revenge will be terrible for society.

As George Fletcher wrote about retributivism in Rethinking Criminal Law: “It is not to be identified with vengeance or revenge, any more than love is to be identified with lust”.

It is critical we know the difference.

PolicyWTF: Ulta-Pulta Tax

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Pranay Kotasthane

Last week I came across this piece of news: Govt moves SC against Bharti Airtel’s ₹9.23 billion GST refund. The details of this specific case aside, you would have heard that the government is struggling to refund the input tax credit (ITC) it owes to businesses, ever since the GST was introduced. Essentially, the government didn’t anticipate the volume of ITC being claimed. As a result, it is far behind its payments and has sucked out working capital from businesses.

But, have you wondered why are the GST refund claims so high?

The main reason is this week’s PolicyWTF: the inverted duty structure.

What’s tax policy for if we can’t make a pig’s breakfast out of it? We expect a tax policy to perform miracles — solve India’s inequality problem, create an aatmnirbhar Bharat, create employment, maybe even produce vibhuti from thin air. In search of such a tax policy that does all these things, we ended up with a GST that has way too many rates.

Inadvertently, this resulted in some raw materials being taxed at a much higher rate than the final product. For example, the tax on rubber used in hawai chappals is a mighty 18 per cent. Why it is so high I have no idea. On the chappals itself, the tax rate is just 5 per cent presumably because we have to save this laghu udyog. This situation is what’s called an inverted duty structure.

This results in refunds because input taxes claimed for credit exceed the output taxes payable. Let me illustrate. Assume the hawai chappals are sold at ₹120 to customers. The output tax payable would be ₹6/chappal (5 per cent of 120). However, since the GST is a value-added tax, the chappal maker can net out the taxes she has paid for the inputs. Assuming that she purchased rubber of ₹50, she has already paid a tax amount worth ₹9 to her supplier (18 per cent of 50). The net tax to be paid by her is -₹3! This means the government needs to refund this amount to the chappal maker. Ordinarily, such a situation wouldn’t arise if the value added by the chappal maker was really high or if the tax rate on rubber would have been the same or less than the one on the chappal.

Examples of such an inverted duty structure abound in the Indian GST. Textiles, housing, and many other sectors are afflicted with this problem. The government, of course, delays paying these refunds, resulting in even more emotional atyaachaar of businesses.

The lesson from this touching story: redistribution and equity should be one of the goals of the expenditure side of the budget. Raising revenues shouldn’t be tasked with this goal at all. Broadening the base, lowering the tax rates for all individuals and companies, and getting rid of tax exemptions is more progressive than a highly progressive GST.

PS: A second-order effect of such an inverted duty structure is that it creates incentives for a new class of cheaters: professional refund creators. Read this ThePrint.in report:

In a case from last year, authorities found that a group of people created a network of 500 firms, including fake manufacturers of ‘hawai chappals’, across states, other intermediary firms and fake retailers to claim and encash fake credit… the group managed to create fake credit amounting to Rs 600 crore before the tax authorities cracked down.

India Policy Watch 2: ‘Persecution’ Of The Privileged

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

One view about journalists is they get paid to ask questions and write things that their subjects want to avoid. I concur with William Randolph Hearst’s dictum: “News is what someone else does not want printed: everything else is advertising.” Though this is often wrongly attributed to George Orwell.

Two Of The Same Kind?

My limited exposure to journalism has convinced me it is a fine profession ruined by journalists. This is truer for business journalism where subject matter expertise tends to be limited and deeper dives are difficult because of lack of access. But businesses left unchecked can and often do, take advantage of the society. I believe a dogged journalist with a healthy dose of scepticism about everything a company’s PR throws at them can uncover truths that small armies of auditors and regulators can’t. Examples abound: Cambridge Analytica-Facebook, Theranos and recently, Wirecard.

I can see the social good that sharp business journalists do.

My limited exposure to VCs has convinced me it is a fine profession ruined by people who have rarely run a business for any length of time. That hasn’t stopped them ever from sitting across an entrepreneur and telling them how to scale their business or change their strategy. But risk capital is necessary to spur innovation. VCs arrange for the risk capital and bet on ideas early. This has allowed thousands of young entrepreneurs to dream big, build new products, create millions of jobs and disrupt existing business models.

I can see the social good that perceptive VCs do.

Silicon Valley Versus East Coast Media Elite

Last week these two got into a public spat. A good account of the events is here.

Here’s the plot summary. Taylor Lorenz writes for the New York Times where she covers internet culture (she reviews a lot of TikTok videos and Instagram posts). She posted a tweet on Wednesday last week criticising Steph Corey, the CEO of Away, a direct-to-consumer luggage start-up. Over the last six months, Away has been receiving negative coverage for its toxic work culture with Corey leading the way in mistreating employees.

In response, Corey posted several Instagram stories in late June lashing out at media companies. Lorenz tweeted a response to Corey. Balaji Srinivasan, entrepreneur and a former general partner at the storied Silicon Valley VC firm, Andreessen Horowitz, tweeted back at Lorenz terming journalists like her ‘sociopaths’.

It went south from there. Other VCs (Paul Graham, Jason Calacanis) joined in complaining about the ‘takedown’ culture of media. A leaked audio recording from Clubhouse, an invite-only audio digital chat site that has predominantly VCs and entrepreneurs as its members, went viral. The recording has Silicon Valley millionaires complaining about tech media and east coast elites peddling untruths, advancing a ‘cancel’ culture and persecuting hardworking, innovative founders who are ‘building’ things that change the world.

From Vice:

Srinivasan, formerly a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, claimed that "the entire tech press was complicit in covering up the threat of COVID-19," and claimed that relying on the press is "outsourcing your information supply chain to folks who are disaligned with you," comparable to the United States having outsourced its medical supply chain.

"When it comes to our industry, there’s a really, really toxic dynamic that exists right now," Nait Jones, an Andreessen Horowitz VC, said on the call while speaking about recent reports about abuse in the tech industry. "Because those stories were so popular and drove so much traffic, they also created a market for more of those stories. They created a pressure on many reporters to find the next one of those stories inside of a fast-growing tech company because those stories play very well on Twitter, especially around protecting vulnerable people."

It is a bit surreal to imagine this lot as the little guys taking on the establishment. But there you have it. Soon, others from media joined in and it was cola and popcorn time for all of us.

Save us the trouble of answering your questions

At the heart of the complaint against media is this. We are providing risk capital, the founders are building things that will make society better while you are concocting negative stories that distract us from our mission. There’s some merit in this argument. In the last 40 years, capital gain taxes have come down the world over and pension funds have been allowed to invest a part of their huge corpus in private equity funds. This has been channelled by scores of VC/PE firms to build a thriving start-up culture around the world. This is a positive for the society.

But there are questions:

Are we going through the peak of human innovation and scientific breakthroughs because of the enormous risk capital sloshing around? The answer is probably no. There is a detailed paper by Tyler Cowen and Ben Southwood ‘Is the rate of scientific progress slowing down?’ which examines this in great detail. This is what the paper concludes: “To sum up the basic conclusions of this paper, there is good and also wide-ranging evidence that the rate of scientific progress has indeed slowed down, In the disparate and partially independent areas of productivity growth, total factor productivity, GDP growth, patent measures, researcher productivity, crop yields, life expectancy, and Moore’s Law we have found support for this claim.”

What kind of innovation is being supported? To paraphrase Peter Thiel, we wanted flying cars, instead, we got 140 characters. The VC/PE model has an investment time horizon of 5-7 years. This isn’t the patient capital needed for a fundamental breakthrough in technology or pure science. There’s not a lot of risk capital supporting research in medical sciences, healthcare or clean-tech to name three areas that could do with more capital. Instead, the incentives of VCs are aligned in a way to ‘overfund’ a specific trend as a herd. Delivering food, luggage (heh) or a pet walker (haha) direct to consumer has some social benefits but they aren’t the biggest problems confronting humanity.

Do tech entrepreneurs and VCs get a bad press all the time? My media diet is quite healthy, and I would say no. Entrepreneurs and star fund managers have been feted like never before. They give TED talks, do fireside chats and make predictions about the future in books, podcasts and industry conferences. These are all covered in a positive light. The bad press is but a fraction of their total coverage.

Do they deserve to be questioned? Well, why not? Public figures deserve scrutiny. Also, the tech start-up and VC complex hasn’t been a model of upright behaviour all the time. The use of vanity metrics to project their businesses, playing up valuations in media, collecting extensive data while keeping users in dark, abusing that data, many instances of toxic work culture and playing fast and loose with ESOPs are all stories that need to be written. The lack of transparency has meant journalists have to eke out a story from the little validated information that comes their way. Some of them will be false. But that doesn’t negate the wider good these stories do for the ecosystem. It should be in the interest of the VC-founder community to have the media ask these questions to keep everyone honest. To imitate the worst of mainstream politics and brand them as ‘fake news’ sets a dangerous precedent.

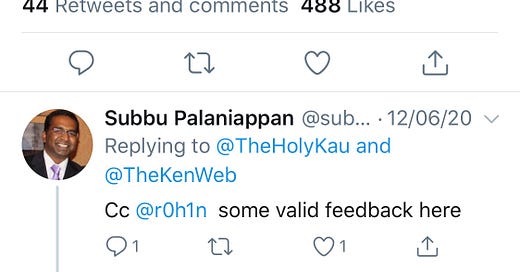

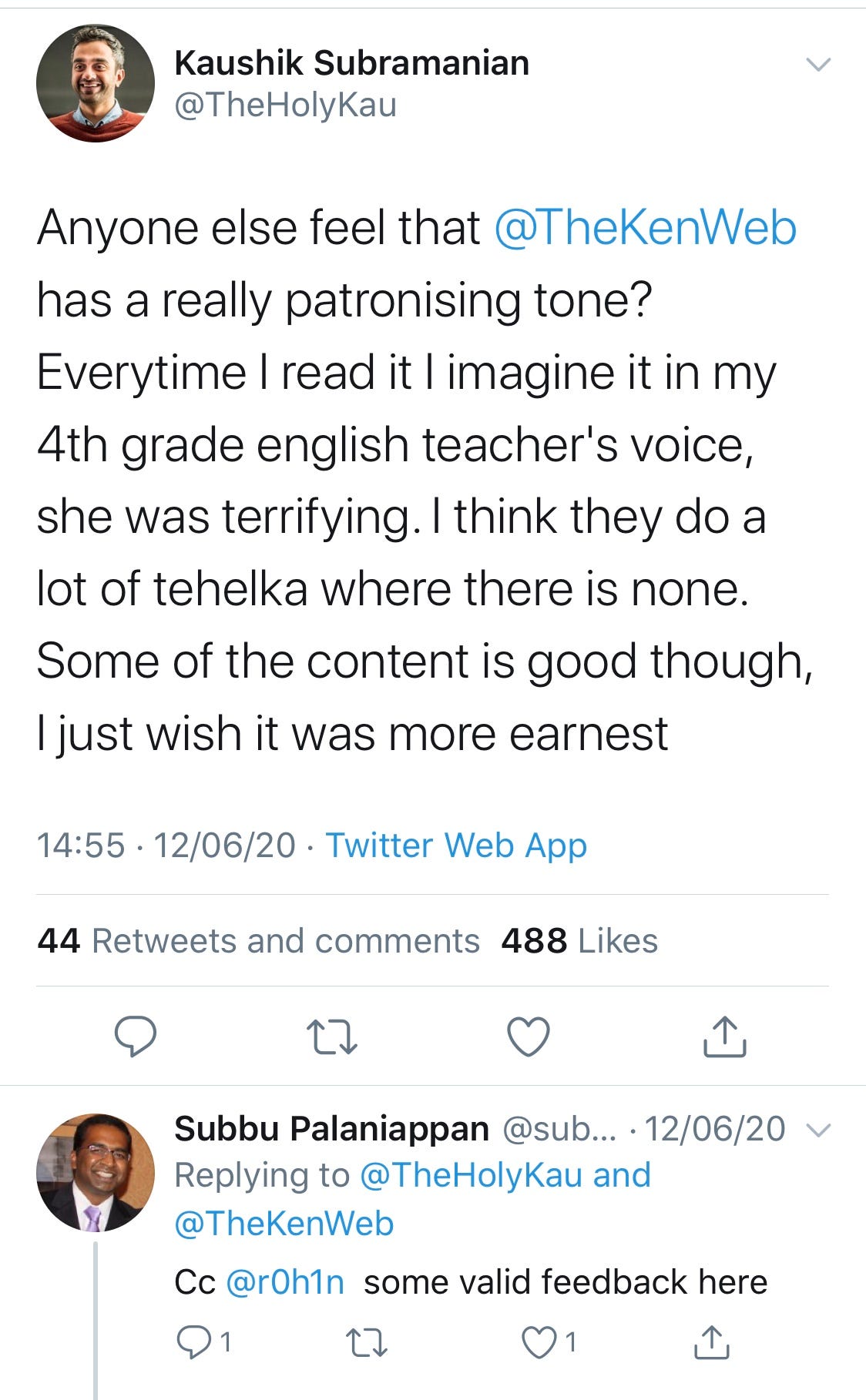

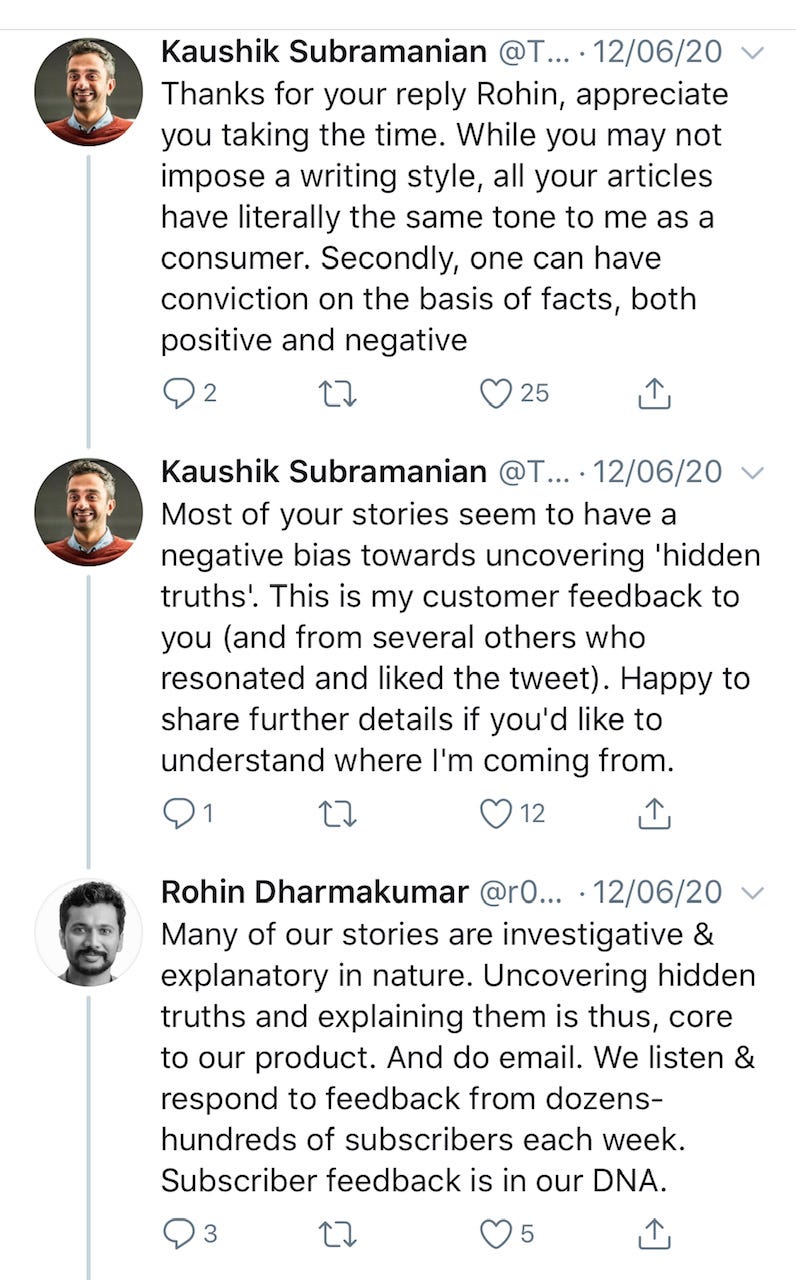

I was speaking to a VC friend the other day about this and he pointed to me a somewhat similar but milder argument that played out on Twitter India about a month back between The Ken, an online media house focusing on business, tech and start-ups and few VCs and readers of The Ken.

The core argument is The Ken is into the ‘gotcha’ school of journalism relying on scoops and gossips to pull down start-ups and their founders. The overwhelming advice to The Ken in this twitter thread was to change their ‘tone’, do positive stories and restore some ‘balance’ in their coverage. (As an aside, we also discovered the editor of The Ken, Rohin Dharmakumar, reads our little public policy newsletter.)

As a long-time subscriber to The Ken and a follower of tech and start-up news in India, I think we need probably ten ‘Kens’ to restore the overall balance of coverage of VCs and start-ups in India.

Matsyanyaaya: Trade Policy as a Tool of Coercion

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

The ongoing trade war between the US and China has highlighted, once again, how trade policy can be deployed as a tool of coercion. Whether it will be effective is not something that I know enough about. But what interests me is this: what are the conditions under which bilateral trade policy can be used as a tool for coercion?

The zeroth condition is that there must be a substantial trade relationship between the to-be-coercive state and the to-be-coerced state. Failing this condition, trade can at best be used as a tool for inducement but not coercion. For example, India cannot use trade as a tool for coercion with Pakistan because there is barely any trading relationship between the two states.

The next condition is that the coercive state must be an overwhelmingly large market compared to the coerced state. Product bans and raising tariffs can be potent tools only if the losses incurred to the coerced state are significant. It is precisely this condition that helped imperial China intimidate many of its small neighbours. The message to all its tributary states was clear and consistent across centuries: we have everything in abundance here. It is you who needs access to our market. So, pay tributes and kowtow to the Emperor or you shall never have trading rights.

Robert Blackwill & Jennifer Harris have earlier described how Russia has repeatedly used trade as a tool for coercion against its smaller neighbours.

In the recent past, Georgian wines, Ukrainian chocolates, Tajik nuts, Lithuanian and even American dairy products, and McDonald’s have all fallen afoul of sudden injunctions… While dealing a significant blow to the Ukrainian economy, Moscow’s geoeconomic moves served, first, to remind Ukraine — and others in the region — of the consequences of decreasing ties to Russia in favour of the European Union; second, to reinforce Russia’s role as an economic regional hegemon; and third, to prevent the continued expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation to Russia’s borders. Facing Russian threats on countless levels, Ukraine halted its plans to sign deals with the EU at the November 2013 Eastern Partnership summit in Vilnius. [War by Other Means, Blackwill & Harris]

The third condition is that the coercive state should have a bilateral trade deficit with the coerced state. This is counterintuitive — most people regard trade deficit as a liability rather than an asset. But it is this deficit which lends a dimension of intimidation to trade policy. This is precisely the reason why the US could use this tool in the first place against China. There is a range of goods on which the US runs a bilateral deficit with China.

My contention is that the presence of all three conditions is necessary for the use of trade policy as a tool for coercion. Seen from this lens, the US trade war against China satisfies conditions one and three but does not meet condition two. Hence, its effect on China is likely to be limited.

In general, trade policy’s effectiveness as a coercive tool additionally depends on what is being demanded from the coerced state. It also depends on the ability of the coercing state to incur the losses resulting from retaliatory actions by the coerced state.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Pratap Bhanu Mehta in The Indian Express on why strong-arm tactics unleashed by the state can’t be a stand-in for law and order.

[Interview] Greg Epstein interviews Anandh Giridharadas on his book, Winners Take All where they discuss Silicon Valley VCs and entrepreneurs as the priests in the new tech religion. There’s a telling quote by Giridharadas quote: “Because [many] are truly possessed of the feeling that leaving them alone, and letting them do whatever they want to do, and grow however they want to grow, is what is best for the world.”

[Podcast] What are India’s options against the People’s Republic of China’s arrogance? What are the costs and benefits of banning apps of Chinese companies? Can economic power be exercised to hurt China without incurring significant costs? Saurabh and Pranay tackle these questions in this episode of Puliyabaazi.

That’s all for this weekend. Read and share.