This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PS: If you enjoy listening instead of reading, we have this edition available as an audio narration courtesy the good folks at Ad-Auris. If you have any feedback, please send it to us.

India Policy Watch: Thinking About Digital Colonialism

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

The unbridled power of large digital platforms is back in focus. Last week Google India announced all apps within Play Store must use its billing system that charges a 30 per cent commission on all transactions. The Indian start-up community that has been angling for raising barriers for global platforms to access domestic market lost no time in pushing back against the ‘Google Tax’. That seems to have worked. Google has postponed this move to April 2022. Google (and Apple) claim this commission is the compensation for their efforts at keeping their stores safe and secure.

Meanwhile, the US Congressional investigation into the power of Big Tech (Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google) concluded last week with a voluminous 450-page report. The report indicts them in no uncertain terms:

"These firms have too much power, and that power must be reined in and subject to appropriate oversight and enforcement. Our economy and democracy are at stake.”

The recommendations (pg 378 onward) to rein in these companies and restore competition in the digital economy however cover familiar grounds – structural separation of lines of business, curbs on acquisitions, allowing interoperability and open access, checking abuse of bargaining powers and strengthening antitrust laws and enforcement. You could almost use the same recommendations a century ago when looking to control railroad or oil monopolies. Surely, these will be useful (if they eventually translate into laws) to bring a semblance of control over Big Tech. But will they be enough?

I don’t think so.

The traditional way of looking at monopolies is to understand the factors that lead to their creation and the abuse they inflict or the harm they do to the customers and the society. The sources of monopoly power usually are technology, control of natural resources, access to capital or lack of alternatives in the market. This power is then abused by the monopolist. The most common abuse is that of being a price maker that maximises profits. The usual antitrust laws attack both the source and the abuse of monopoly power.

But there’s a problem in regulating Big Tech with these antitrust laws: the source of their monopoly power and the harm they do to societies is orthogonal to how the traditional monopolies operated.

Given this, how should we think about regulating them? We can begin by analysing the dominance of these players in the digital economy using the traditional monopoly framework and then going beyond it.

I will elaborate on this next.

Digital monopolies are unavoidable: There’s no single source of monopoly power for them. Its an alchemy of network effect, bundling of services, a bottomless pit of capital and high exit barriers that create a lock-in for customers. This makes it a winner-takes-all market. Infusing competitive intensity by breaking up these firms on lines of business or creating a ‘local’ alternative won’t work because these Big Tech ‘babies’ will soon turn into a monopoly.

Two-sided platforms: Most big tech firms have been successful in creating two-sided platforms of buyers and sellers. Sometimes this is apparent to the end customer (for instance, Uber) but often this isn’t (Google or Facebook). In these two-sided platforms, the tech firms tend to be monopolies (dominant seller) on one side and monopsonies (dominant buyer) on the other. So, Google has a near-monopoly on search that it provides for free. On the other hand, for any company wanting to advertise on digital platforms, Google is the dominant buyer. It actually auctions keywords. This two-sided dominance is different from the monopolies of the past.

There’s no ‘one’ business: In the earlier era, the dominance of a monopoly could be easily understood because of the distinct nature of their business. A railroad company was just in that business. So was a telecom company. But it’s difficult to categorise the big tech players into a single type of business. Amazon can position itself as a tech company to investors, an e-commerce platform to sellers and a retailer to regulators. Facebook is a social media platform whose business isn’t easy to define. Maybe it is a publisher or a media company, but it isn’t structured like one. Maybe it’s a community that brings the world closer (ha!). What’s worse the companies themselves don’t know where they will end up in future. Facebook has long wanted to start a digital currency and become a financial services company. Amazon has become the largest cloud service provider plus an on-demand entertainment platform while Google has its moonshots including wanting to be an autonomous car company. Which business of these companies do you regulate?

Asymmetry of power and knowledge: In a traditional monopoly situation, the customers sense the harm in the form of exploitative prices or a lack of voice in making their grievances heard. This is almost absent here. On any traditional yardstick of customer satisfaction – loyalty, retention or advocacy – these platforms score high. The pervasive nature of these platforms is such even a few minutes of outage creates widespread anxiety. Most customers have no sense of their exploitation despite the platforms knowing and using almost everything about the customer. This is the definition of absolute asymmetry where one side doesn’t even know there’s asymmetry.

Data appropriation: The ‘natural resources’ over which these platforms have a monopoly are our attention and the data that flows from the rhythms of our daily lives. The attention and data are then transmuted into factors of production and monetised in many different ways. All of this is done through our consent. Life is too short to read the terms and conditions while signing up to these platforms. The unanticipated consequences of handing over these ‘natural resources’ are difficult to fathom for most people. From nudging you to buy something you didn’t need, to flooding your timelines with propaganda that’s aimed at you – the algorithms control your behaviour. This monopoly power is difficult to dimension. Even the platforms often don’t understand it. The frequent defence that Facebook puts up in various senate hearings attests to this. They don’t know how to control what’s coming up in your timelines. The program knows your ‘persona’ and it does what it has to do.

Geographic boundaries: The nature of the digital economy is such that these monopolies don’t have geographic boundaries. The seamless nature of the platform and its monopoly on attention and data as resources ensure they can extend their monopoly anywhere in the world. How do you regulate a global monopoly? Do you take a nationalistic agenda and stop them at your boundaries? That will only mean setting up domestic monopolies. Who do you trust more? A global monopoly that adheres to the best corporate governance norms or a domestic monopoly in countries with weak institutions or that lack democratic accountability?

Loss of freedom and the end of thought: The data and attention appropriation done through these platforms constrain our choices: we live in echo chamber of our opinions, we buy things that are suggested to us and we see a version of reality that’s tailor-made for us and that no one else is seeing. Often the term ‘digital colonialism’ is bandied about when talking about Big Tech. This lack of freedom to be oneself, discover things on our own and not be dispossessed of our right to choose is what colonialism is about. That we have done this voluntarily and for convenience and value that’s quite apparent is what makes this difficult to legislate.

A new form of capitalism: One way to manage this kind of monopoly is to let things play out. To let evolution take care of this. There will be a period of monopolies reigning across sectors. Soon there will be overlapping of interests and territories among them. It is attention and data that are being monopolised and beyond a point, they are finite too. They will fight among themselves, get bruised and breakup in the process. Also, there will always be newer opportunities that will attract smaller, nimbler firms that will beat these incumbents. This has happened throughout history and there’s no reason to believe this time is unique. A new form of capitalism will evolve after a period of digital colonialism. It won’t be better or worse. It will just be different.

What’s resistance then?

It is not easy to legislate the resistance to these monopolies. The policymakers are using the tried and tested tools to counter them. They will yield some benefits in the short-term. But they will be largely ineffective for the reasons we have mentioned above. The other options like moral pressure to delete an app or the self-control to stay away from these players can’t scale up. Such measures also don’t consider the huge benefits these platforms deliver to us. The truth is technology will remain a step ahead of us. The idea that we can tame it is also a non-starter.

There are proponents of ethical algorithms who believe a societal code or a legislative norm for how algorithms are to be used is the way ahead. There are others who believe handing over control or making users aware of how their data is being used and compensating them for it. This will make it a fair bargain. Maybe it will. These are early days of policymaking in this area. There’s a need for deeper philosophical and sociological work in this space that will enable our thinking in how to legislate this. Until then we think the house report is a good place to get things started.

A Framework a Week: What Makes an Asset Strategic?

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

From AI to semiconductor chips and from data to rare earth metals, a whole lot of assets are labelled as being strategic by many governments and analysts. And yet, there’s no conceptual clarity as to what the term strategic means.

Most often, it is narrowly used to describe assets that are critical for the military. In this definition, only goods that can be used for war or to threaten war qualify as strategic, an obvious example being nuclear technology.

By another definition, assets that are critical for the economy or military and have no other easily available substitutes, qualify as strategic. For example, oil becomes a strategic asset for India using this definition.

So what really is strategic then? I was lucky to stumble upon a framework which tackles this fundamental question. Jeffery Ding and Alan Dafoe in their paper The Logic of Strategic Assets: From Oil to AI theorise that:

Strategic Level of Asset = Importance * Externality * Nationalization

The strategic level of an asset is a product of the following three factors:

Importance: an asset’s economic and/or military utility (some sectors, e.g. freight transport, contribute more to economic growth than others, e.g. high-end fashion).

Externality: the economic and/or security externalities associated with an asset, such that uncoordinated firms and individual military organizations will not optimally attend to the asset. (e.g. the positive externalities generated by research into foundational technologies, which private actors under-invest in because they do not capture all the gains from spillovers).

Nationalization: the degree to which these externalities differentially accrue to the nation and one’s allies, and not to rivals (e.g. fundamental research in medicine has positive externalities, but they may easily diffuse to other rival nations, which limits an asset’s strategic level).

What’s interesting here is that the authors apply the economic concept of externality to a question in the national security domain. They contend that some assets and technologies demonstrate the characteristics of an externality-like market failure. This means that uncoordinated firms and individual military organisations underproduce these strategic assets and hence the attention of the State is required.

These externalities are distilled into three forms:

“Cumulative-strategic logic involves assets and sectors with high barriers to entry linked to cumulative processes, such as first-mover dynamics, incumbency advantages, and economies of scale. These high barriers to entry lead the market to under-invest, and military organizations to require explicit state support to achieve nationally optimal investments. Aircraft engines [1945-present] serve as a representative example, as high research and development costs associated with these complex technical systems make it so that only a handful of firms can compete.

Infrastructure-strategic logic involves assets that generate positive spillovers across the national economy or military system, which sub-national actors (e.g. firms or militarybranches) under-invest in because they do not appropriate all the associated gains. These are often central technologies that complement and upgrade the national technological system. A representative example is railroads [1840-1860].

Dependency-strategic logic involves assets whose supply is concentrated in a limited number of suppliers. Due to the lack of substitutes, these assets are often vulnerable to supply disruptions… Individual firms do not fully internalize the downside of a cut-off for the nation’s economy or military, for which continued access to these dependency-strategic assets is at risk due to the lack of substitute goods and alternative suppliers. Nitrates [1914-1918] are a representative example, as the British naval blockade prevented Germany from importing nitrates from Chile, the world’s principal supplier.”

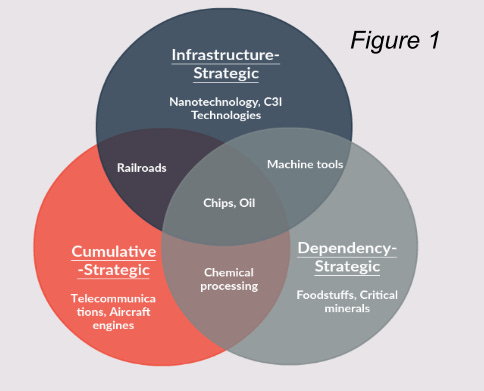

These three logics are not mutually exclusive. The authors argue that states should pay especially close attention to those technologies and goods that exhibit multiple strategic logics. The figure below illustrates the overlap:

(Source: Jeffery Ding and Alan Dafoe, The Logic of Strategic Assets: From Oil to AI)

This framework is a really useful tool for prioritising strategic assets. Using this framework, which assets qualify as being strategic for India, you reckon?

Poetry In Public Policy: Louise Gluck

—RSJ

Lousie Gluck has won the Nobel Prize for Literature (2020) for “her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”.

“She writes oneiric, narrative poetry recalling memories and travels, only to hesitate and pause for new insights. The world is disenthralled, only to become magically present once again.”

Gluck possesses a direct, natural style that shines a light on our imperfections with a detached clarity. But that doesn’t take away from the beautiful, lyrical compositions that stay with us for long. She is one of the originals.

Nostos by Louise Glück

There was an apple tree in the yard --

this would have been

forty years ago -- behind,

only meadows. Drifts

of crocus in the damp grass.

I stood at that window:

late April. Spring

flowers in the neighbor's yard.

How many times, really, did the tree

flower on my birthday,

the exact day, not

before, not after? Substitution

of the immutable

for the shifting, the evolving.

Substitution of the image

for relentless earth. What

do I know of this place,

the role of the tree for decades

taken by a bonsai, voices

rising from the tennis courts --

Fields. Smell of the tall grass, new cut.

As one expects of a lyric poet.

We look at the world once, in childhood.

The rest is memory.

Parable of Hostages by Louise Glück

The Greeks are sitting on the beach

wondering what to do when the war ends. No one

wants to go home, back

to that bony island; everyone wants a little more

of what there is in Troy, more

life on the edge, that sense of every day as being

packed with surprises. But how to explain this

to the ones at home to whom

fighting a war is a plausible

excuse for absence, whereas

exploring one’s capacity for diversion

is not. Well, this can be faced

later; these

are men of action, ready to leave

insight to the women and children.

Thinking things over in the hot sun, pleased

by a new strength in their forearms, which seem

more golden than they did at home, some

begin to miss their families a little,

to miss their wives, to want to see

if the war has aged them. And a few grow

slightly uneasy: what if war

is just a male version of dressing up,

a game devised to avoid

profound spiritual questions? Ah,

but it wasn’t only the war. The world had begun

calling them, an opera beginning with the war’s

loud chords and ending with the floating aria of the sirens.

There on the beach, discussing the various

timetables for getting home, no one believed

it could take ten years to get back to Ithaca;

no one foresaw that decade of insoluble dilemmas—oh unanswerable

affliction of the human heart: how to divide

the world’s beauty into acceptable

and unacceptable loves! On the shores of Troy,

how could the Greeks know

they were hostages already: who once

delays the journey is

already enthralled; how could they know

that of their small number

some would be held forever by the dreams of pleasure,

some by sleep, some by music?

Matsyanyaaya: Narratives about China’s Pandemic Response

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

Narrative 1: The Chinese party-state, which covered up the COVID-19 outbreak in the initial stages, is the world’s number 1 enemy.

Narrative 2: After the initial shock, China has been remarkably successful in containing the outbreak, like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

Floating around are these two distinct narratives about China's COVID-19 response. On the surface, these two narratives appear to conflict with each other. Scratch the surface and you’ll find that both narratives are actually in harmony with each other.

Quite a few opinion pieces perceive these two narratives as being in conflict. Such articles explain, with awe, that even though China bungled up initially, it was able to get back on its feet quickly, curb the rise in infections, and take the lead in vaccine research. How does one explain this apparent contradiction?

In my view, both these narratives are in harmony and not in conflict. I say this because the initial failures and the later 'successes', both, can be explained by the same incentive structure that characterises the Chinese authoritarian party-state.

In the initial days, government officials in Wuhan were competing against each other in hiding the facts lest the heavy hand of the authoritarian regime fall on them. Local officials claimed there was no person to person transmission, medical professionals who raised alarm were silenced, and state media refused to speak a word about the disease. Even after nine months since the outbreak was first reported, the party-state continues to deflect the blame, claiming success in reporting the outbreak first on one hand, and blaming everyone else in the world for starting the pandemic on the other.

These same incentives at least partially explain the later successes as well. First, the authoritarian setup was well-suited to enforce strict lockdowns for long periods at the citizens’ expense. Next, in a desperate urge to project the party in a positive light, many thousands of people were vaccinated without the completion of clinical trials. Despite a history of vaccine safety scandals, the authoritarian regime was ready to risk the lives of citizens in the hope of regaining some lost pride.

By taking these dangerous shortcuts, it is quite likely that China’s vaccine candidates will be the first to reach the market. China might even come up with a global vaccine campaign and label it the medical silk road.

Despite all this facesaving, if China is the first to get to the market with a vaccine (and that’s a big if), other states’ perceptions are unlikely to make a U-turn. The damage is already done. All projected successes now are like apologising after slapping an unsuspecting person for no reason.

The world is increasingly coming to terms with the reality of engaging with China — there are clear short-term gains to be had but the downside risks are way too high. China’s response has shown that these downside risks are not just high but they are always lurking beneath. It will take China more than a few interest-free loans and vaccine diplomacy to make this risk perception disappear.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Emily Birnbaum and Issie Lapowsky in the Protocol on the findings and recommendations from the House antitrust subcommittee’s report on Big Tech

[Interview] Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias on The Nuances of Data Colonialism and taking a sociological view on digital monopolies.

[Article] David Brooks has a compelling diagnosis of American society over the last two decades. A lot of it applies to India as well.

Share this post