This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PS: If you enjoy listening instead of reading, we have this edition available as an audio narration courtesy the good folks at Ad-Auris. If you have any feedback, please send it to us.

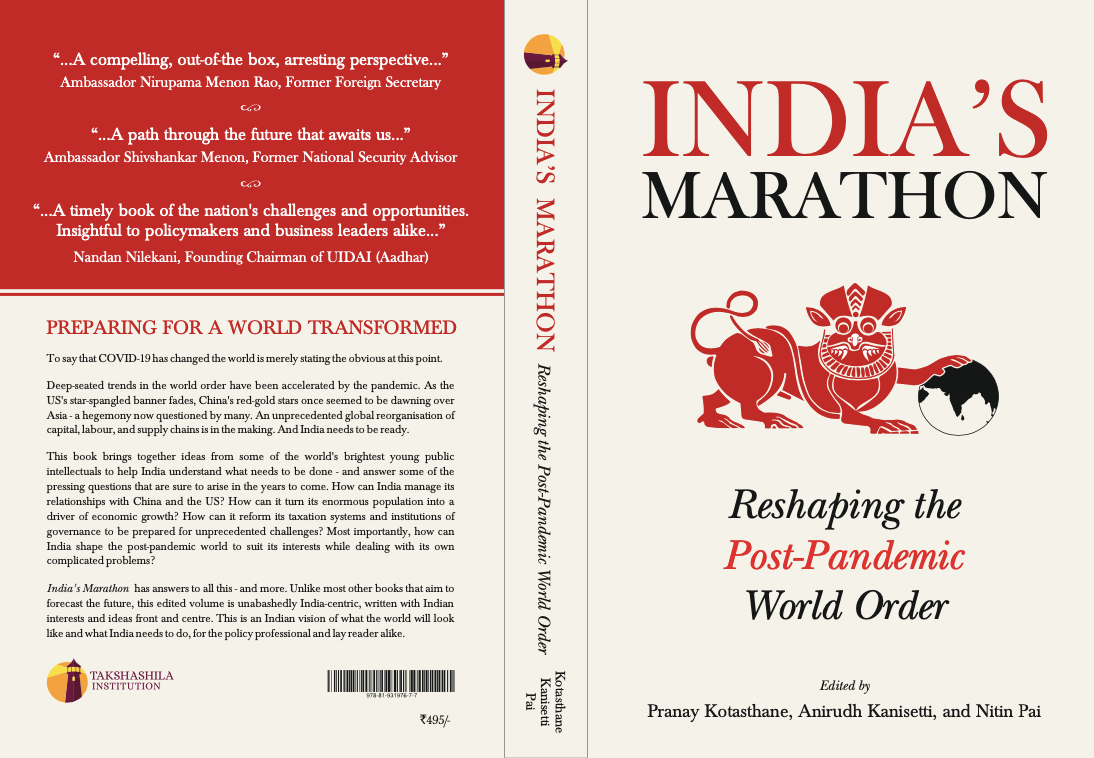

New Book Out! — India’s Marathon: Reshaping the Post-Pandemic World Order

— Pranay Kotasthane

I’ve co-edited India’s Marathon — a collaborative effort that brings together bold ideas on India’s place in the changing world order from some of India’s finest young thinkers.

(India’s Marathon, book cover by Anirudh Kanisetti)

Don’t take my word for it. This is what Ambassador Shivshankar Menon writes in his foreword:

“This volume poses questions which everyone wants answered but few dare to reply: how will the world order evolve and how can India deal with it? The Takshashila Institution has brought together some of the best minds to answer this question, and to give an Indian perspective on world order issues. Just for this the book deserves to be welcomed. This volume consists of coherent contributions from these scholars covering how India should manage its external relationships and the reforms that India needs to undertake domestically.

… No reader would or should agree with everything in this book. I, for one, am not sure that India’s choice is between alignment and non-alignment any more, or that strategic autonomy is an unattainable goal for India. After all, strategic autonomy by one name or another is what all powers, even superpowers, seek. But this book would have served its purpose if it provokes thought and rational discussion about India’s place in the emerging world, whether it is ‘orderly’ or not. Despite the daunting world that seems likely, and the scale and scope of the necessary domestic reforms outlined in this book, I found it reassuring that so many contributors found it possible to rationally conceptualise these issues from an Indian perspective, and to map out a path through the dimly sensed future that awaits us.”

Pranay Kotasthane, Anirudh Kanisetti, Nitin Pai (editors). India's Marathon (Kindle Locations 144-150). The Takshashila Institution. Kindle Edition.

This Twitter thread lists all chapter ideas and contributors. It’s a stellar list, I tell you.

Get your copy from Amazon India. Do give it a read!

Global Policy Watch: Fukuyama (et al) And The ‘Middleware’ Solution To Social Media Monopolies

— RSJ

Twitter India did a first last week. It labelled a tweet by BJP IT cell head as ‘manipulated media’. It claimed the label was based on its Synthetic and Manipulated Media policy. This was a policy launched by it in February this year. The rule for its user states:

“You may not deceptively share synthetic or manipulated media that are likely to cause harm. In addition, we may label Tweets containing synthetic and manipulated media to help people understand their authenticity and to provide context.”

Curbing Digital Colonialism

It is unclear if Twitter found no such tweets in India since February that satisfied the criteria for manipulate media. Surely, this wasn’t the first instance of false information shared by a blue-tick user in India. In any case, a beginning has been made and it will be interesting to see where and how far it will go with this. These steps are part of similar efforts by other social medial platforms to self-regulate themselves as they come under increasing government and regulatory scrutiny. There is a greater urgency among regulators around the world to curb the abuse of the dominant positions of the big tech platforms.

EU pursued antitrust charges against Google for over a decade. In 2018, it fined it nearly $10 billion. But not much has come out of it. Google was left to devise its own measures to offer a level playing field to its rivals. Google continues to dominate the search-engine market in Europe with over 90 per cent market share. The U.S. Justice Department last month sued Google for violating federal antitrust laws in running its search and advertising business. Also, the US Congressional investigation into the power of Big Tech (Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google) concluded in September this year with a voluminous 450-page report. The report indicts them in no uncertain terms:

"These firms have too much power, and that power must be reined in and subject to appropriate oversight and enforcement. Our economy and democracy are at stake.”

India hasn’t yet taken a concrete view about the dominance of Big Tech but there are rumblings. Last month, India’s antitrust regulator (CCI) opened an investigation against Google based on complaints from the start-up ecosystem. The practices of ‘forcing’ the app makers to exclusively use its billing system for in-app purchases and for bundling its payments app with Android smartphones sold in the country are under the regulatory lens. Last month, India brought all OTT platforms under the purview of its Information and Broadcasting ministry by changing the GoI (Allocation of Business) Roles, 1961. And it has been considering regulating the social media platforms and their content for a while now.

Not The Usual Lens

There are three key points that we have made about regulating Big Tech and social media platforms:

Antitrust regulators take the old Chicago school view to monopolies. This looks at monopolies through the economic lens of consumers and checks if they are being harmed by the dominance of monopolies. This is difficult to prove in case of Big Tech monopolies who provide most of their services for free and have deep customer loyalty.

The nature of these monopolies is quite different from those of the past. These players have appropriated huge amounts of data, run 2-sided platforms, have asymmetrical knowledge and power over their users, and can easily move into newer businesses based on these strengths. The traditional measures to curb the monopolies like breaking them up or stopping a line of business are difficult to implement.

Economic dominance is only one part of their power. It is the political dominance or the dominance of thought that can be more insidious. Like we wrote in edition #74,

“the data and attention appropriation done through these platforms constrain our choices: we live in echo chamber of our opinions, we buy things that are suggested to us and we see a version of reality that’s tailor-made for us and that no one else is seeing. Often the term ‘digital colonialism’ is bandied about when talking about Big Tech. This lack of freedom to be oneself, discover things on our own and not be dispossessed of our right to choose is what colonialism is about.”

The current antitrust laws have nothing to manage this.

In short, our view was the minimum acceptable price of Big Tech businesses to exist wasn’t zero.

It was you. Your data and your liberty.

In the normal course of events, politics would be about contestation of ideas and narratives in the political marketplace. And the best or the most acceptable idea would surface from this that would guide the polity. But social media platforms engineer a failure in these markets. The ideas that get pushed to your timelines haven’t won their duels in the marketplace of ideas. They have been programmatically fed to you. That program can be gamed. And Big Tech isn’t willing to solve this problem on its own. It took a long time to even acknowledge it is a problem.

We had concluded edition #74 with these lines:

“These are early days of policymaking in this area. There’s a need for deeper philosophical and sociological work in this space that will enable our thinking in how to legislate this.”

A Novel But Half-formed Approach

As if on cue this week we had Francis Fukuyama, Barak Richman, and Ashish Goel publish an article in Foreign Affairs titled How to Save Democracy From Technology: Ending Big Tech’s Information Monopoly. The article picks up the core point made by us. The antitrust regulations are using old tools to solve the economic problem. They may or may not be enough. But they don’t even begin to address the political costs of the Big Tech monopolies. The solution offered is not exactly fleshed out in the article, but it is important because it goes beyond the conventional thinking that has dominated this space.

They write:

“The economic case for reining in Big Tech is complicated. But there is a much more convincing political case. Internet platforms cause political harms that are far more alarming than any economic damage they create. Their real danger is not that they distort markets; it is that they threaten democracy.”

It is remarkably similar to the points made by us in the past. The article then picks up the usual solution to break monopoly power – more regulations, breakup, data probability and privacy laws – and dismisses them all before proposing a solution:

“If regulation, breakup, data portability, and privacy law all fall short, then what remains to be done about concentrated platform power? One of the most promising solutions has received little attention: middleware. Middleware is generally defined as software that rides on top of an existing platform and can modify the presentation of underlying data. Added to current technology platforms’ services, middleware could allow users to choose how information is curated and filtered for them. Users would select middleware services that would determine the importance and veracity of political content, and the platforms would use those determinations to curate what those users saw. In other words, a competitive layer of new companies with transparent algorithms would step in and take over the editorial gateway functions currently filled by dominant technology platforms whose algorithms are opaque.”

The solution comes with its own set of problems. The authors acknowledge it and posit this as the start of a conversation to find a solution:

“Many details would have to be worked out. The first question is how much curation power to transfer to the new companies. At one extreme, middleware providers could completely transform the information presented by the underlying platform to the user, with the platform serving as little more than a neutral pipe. Under this model, middleware alone would determine the substance and priority of Amazon or Google searches, with those platforms merely offering access to their servers. At the other extreme, the platform could continue to curate and rank the content entirely with its own algorithms, and the middleware would serve only as a supplemental filter. Under this model, for example, a Facebook or Twitter interface would remain largely unchanged. Middleware would just fact-check or label content without assigning importance to content or providing more fine-tuned recommendations.

The best approach probably lies somewhere in between. Handing middleware companies too much power could mean the underlying technology platforms would lose their direct connection to the consumer. With their business models undermined, the technology companies would fight back. On the other hand, handing middleware companies too little control would fail to curb the platforms’ power to curate and disseminate content. But regardless of where exactly the line were drawn, government intervention would be necessary. Congress would likely have to pass a law requiring platforms to use open and uniform application programming interfaces, or APIs, which would allow middleware companies to work seamlessly with different technology platforms. Congress would also have to carefully regulate the middleware providers themselves, so that they met clear minimum standards of reliability, transparency, and consistency.”

As a new approach to deal with the problem of fake news and lies circulating on social media platforms and making it sit well with the notion of free speech, this is a useful starting point. The control of what kind of content we want to see should lie with us. Like it has always been in media, the content consumer has to be active while engaging with it and the provider passive. Not the other way around.

Matsyanyaaya: The Strategic Consequences of India’s Low Economic Growth

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

Last week I came across a data story in The Business Standard and I haven’t been able to erase off my mind. Krishna Kant writes:

“Over the past 10 years, India’s per capita GDP is up 35 per cent cumulatively from $1,384 in 2010 to $1,877 now. In the same period, per capita GDP in China rose 141 per cent from $4,500 to $10,839, while it doubled in East Asian countries (excluding Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong) from $4,006 to $8,195.

Bangladesh saw the fastest growth with its per capita up nearly two-and-a-half times from $763 in 2010 to around $1,900 at the end of this year. And, Vietnam’s per capita rose 115 per cent from $1,628 to around $3,500.”

There’s a nice chart showing how the India growth story lost its way over the last full decade.

(Source: Krishna Kant, India's 10-year growth one of the biggest laggards in Asia, EM peers, The Business Standard)

The humanitarian consequences of low economic growth are obvious. I won’t bring them up here. The questions I have are concerned with India’s engagement with the world: what would be the strategic consequences of this poor economic performance? Does a decade of slow growth foreclose some options for India? Would India’s position on RCEP have been different had the last decade’s performance been at par with other peers? Would the PRC have been just as aggressive against a more prosperous India?

The search for answers took me back to Sanjaya Baru’s 2002 landmark paper titled Strategic Consequences of India’s Economic Performance. The paper captures what scholars were thinking nearly twenty years ago, just before the golden growth years between 2004 and 2009.

“For India, there is no doubt that the first and most important challenge is that of accelerating the rate of economic growth and development. Economic performance and capability certainly constitute the foundation of national security and power even more so for a developing nation like India. It will define the limits to military capability and alter the relationship between India and its neighbourhood, especially its two major adversaries, namely, China and Pakistan.

The paper’s observations on Pakistan have broadly stood the test of time. The Pakistani military-jihadi complex’s self-defeating policies have strangled the economy in ways that even a nuclear weapons status and use of terrorism as a state policy haven’t been able to offset. The dehyphenation between India and Pakistan in international affairs is now self-evident. However, the story of this last decade is humbling. The gap between the two has increased not because India has done well but because Pakistan has done far worse.

On China, the paper argued:

“The strategic consequences of the economic competition with China are, there- fore, fundamental to India’s future role within Asia and the global system. If India can sustain above average growth (over 7 per cent per annum in the next decade) and if China experiences a deceleration of growth, coupled with domestic political uncertainty, the widening gap between the two civilisational neighbours can be reversed to an extent. If not, China will emerge as the pre-eminent Asian power and force India into accepting its strategic leadership even within south Asia. The key to this strategic rivalry will be the relative economic performance of the two countries. The main strategic challenge for India in the medium term is, therefore, its relative economic performance vis-à-vis China.”

Remarkably prescient. Eighteen years on, the gap between the two countries has only widened. China has been able to forge strong economic ties with all countries in the Indian subcontinent.

Economic Reforms Needed

The paper identified these macroeconomic targets essential from a national security perspective:

Elimination of the revenue deficit, a manageable fiscal deficit, elimination of wasteful subsidies not targeted to the poor;

Low and manageable current account deficit;

Low internal and external debt, low short-term debt in overall external debt;

Profit-generation by public enterprises; privatisation of non-strategic public enterprises;

Self-financing public utilities like power, irrigation water and public transport;

An increase in the tax/GDP ratio to levels reached by rapidly industrialising developing countries of around 15 per cent of GDP from the current low of 9 per cent of GDP.

What struck me was that eighteen years since, many of these targets still remain aspirations.

Lessons for the Future

It is clear now that China’s rapid and sustained economic development over three decades played a fundamental role in transforming its international stature. The bad news for India is that not only did it start on the same path ten years later than China but it also seems to have fizzled out much earlier.

Going ahead as well, India’s economic development will underscore its international role. India’s economic trajectory will decide whether it can play the role of a swing power between the US and China or whether it gets relegated to a weak partner of the US, much like Pakistan is to China. The stakes have never been higher.

We put this rather simply in a flowchart to conceptualise India’s future options like this:

(Source: India in the Post COVID-19 World Order, Takshashila Discussion SlideDoc)

Money Quote: Why Care About Budget Deficits?

— Pranay Kotasthane

Dr M Govinda Rao pointed me to this quote by Martin Feldstein from his LK Jha Memorial Lecture at RBI. Feldstein warned about the adverse consequences of large budget deficits thus:

“Unfortunately, it is easy to ignore budget deficits and postpone dealing with them because the adverse effects of budget deficits are rarely immediate. Fiscal deficits are like obesity. You can see your weight rising on the scale and notice that your clothing size is increasing, but there is no sense of urgency in dealing with the problem. That is so even though the long-term consequences of being overweight include an increased risk of a sudden heart attack as well as of various chronic conditions like diabetes. Like obesity, government deficits are the result of too much self-indulgent living as the government spends more than it collects in taxes. And, also like obesity, the more severe the problem, the harder it is to correct: the overweight man has a harder time doing the exercise that could reduce his weight and the economy with a large deficit and debt is trapped by increasing interest payments that cause the deficit and debt to rise more quickly. I emphasize the analogy to stress the point that budget deficits need attention now even when their adverse effects may not be obvious.”

Enough said.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Interview] Promarket interviews Fukuyama. “A Loaded Weapon”: Francis Fukuyama on the Political Power of Digital Platforms

[eBook] Friedman 50 Years Later series. A collection of 28 essays reflecting on Friedman’s essay on shareholder maximisation

[Reports] US Thinktanks CNAS and CFR make the case for two different multilateral arrangements between powerful democracies to take on China in the technological domain

[Article] Amit Cowshish and Rahul Bedi have a definitive take on India’s defence pensions system.

If you like the kind of things this newsletter talks about, consider taking up the Takshashila Institution’s Post Graduate Programme in Public Policy (PGP) course. It’s a 48-week in-depth online course meant for working professionals. Applications for the Jan 2021 cohort are now open. For more details, check here.

Share this post