Global Policy Watch #1: Chinese Checkers

Global issues relevant to India

— RSJ

As was widely anticipated, U.S. President Biden signed an executive order imposing new, escalated tariffs on Chinese ‘green goods’ imports to signal his commitment to protect the domestic manufacturing sector. On his official X account, he put out the numbers and his intent:

“I just imposed a series of tariffs on goods made in China:

25% on steel and aluminum,

50% on semiconductors,

100% on EVs,

And 50% on solar panels.

China is determined to dominate these industries.

I'm determined to ensure America leads the world in them.”

Strong stuff.

The fact sheet that accompanied the executive order had stronger language.

“China’s forced technology transfers and intellectual property theft have contributed to its control of 70, 80 and even 90 percent of global production for the critical inputs necessary for our technologies, infrastructure, energy and health care — creating unacceptable risks to America’s supply chains and economic security.."

Apart from these, the embargo on exports of high-end chips and hi-tech products to China and sanctions on Chinese companies operating in America continue.

Meanwhile, Trump, in his campaign trail, has called these moves soft while promising to go further on tariffs and bans on Chinese imports. We are just about getting started on the trade wars in my opinion. There’s some difference between the Trump and the Biden approach to counter China as the New York Times points out:

“Mr. Trump wants to tear down the bridges of commerce between the world’s two largest economies and dramatically restrict trade overall. He has pledged to raise tariffs on all Chinese imports, by revoking the “most favored nation” trade status that Congress voted to bestow on China at the end of the Clinton administration, and ban some Chinese goods entirely. He would impose new taxes on all imports from around the world.

Mr. Biden rejects Mr. Trump’s proposals as too broad and costly. He wants to build a protective fortress around strategic industries like clean energy and semiconductors, using tariffs and other regulations. Mr. Biden is also showering companies in those sectors with billions in government subsidies, including for green-energy technologies through the Inflation Reduction Act.”

Either way, global trade is set to lose when politicians start thinking of it as a zero-sum game.

Much of this is being driven by the election year considerations in the US. Biden is trailing Trump in battleground states and he is returning especially poor scores in his handling of the economy. The two of them are ratcheting up their promises to the blue collar workforce in middle America on reviving manufacturing. The higher tariffs are meant to send out two signals. Firstly, to the domestic ‘green goods’ manufacturers, we are going to protect you from China’s overcapacity flooding our markets, and you need to keep your side of the bargain by building up capacity in quick time to match our green transition ambitions. Secondly, it is a message to China that we aren’t going to repeat our past mistakes of letting you play unfairly while we follow all the rules of the global trade game. We will hurt you till you stop playing the dumping game.

Will either of these work?

Let’s see how this will likely play out over the years in the US. At this moment, its domestic manufacturing sector doesn’t have the capital, scale or skills to build the capacity needed for the planned green transition. Top-down industrial policy looks deceptively easy to implement, but as the Indian experience has shown, it is almost impossible to manage every variable when you distort the market through tariffs. Recent history in the US is proof. Take, for instance, the bipartisan infrastructure law that Biden signed in November 2021, where US$5 billion was allocated to build a network of fast chargers along major highways. After more than two years the program has delivered only seven charging stations with some 40 spots where the drivers can charge their vehicles. The funding was meant for opening more than 5000 stations and 20,000 spots. Given the pace so far, it is unlikely those numbers are going to be met in this decade. And why has it gone so slow? Well, each state has to submit their plans to a federal body for getting a piece of that $5 billion pie, their plan then has to be reviewed and approved and then the states can solicit bids from private players to build the stations and then award the funds to the chosen partners. As you might notice, the process set out meant a lot of files going back and forth, government officials lording over business plans and vendors jostling to curry favour with the state officials who will decide on the winning bid. No wonder they have got only seven stations so far. The experience of setting up plants for other green tech products in future supported by grants and tariffs won’t be too different. This will take a lot of time and money, produce less globally competitive goods and increase the price for the American consumers. The taxpayers will pay for it both ways - by subsidising the industry and then paying more for what they produce.

That apart, it isn’t that China will take these tariff blows and not respond. China is still the biggest market for a lot of US manufacturers and any tit-for-tat move will make things difficult for them. From Apple, Qualcomm and Tesla to Nike, Cargill and Hollywood, China is the primary growth market for all. China might also strategically decide to ban exports to the US, especially to its retail sector, to increase the cost for American consumers who have gotten used to low-cost products from China. Inflation is already the primary concern of American voters, and China can easily raise the prices of its exports. China is also deeply integrated with the global supply chain and supplies critical raw materials and parts that find their way eventually into the US manufacturers. Just two elements, Tungsten and Vanadium, of which China is almost the sole global supplier, can be put under the banned list of exports, and the US manufacturers of hi-tech products will have a problem on their hands.

But it isn’t all plain sailing for China. The great rebalancing of the economy from investment-driven to consumption-led growth isn’t going well. The mindless investment and overcapacity in real estate in the past two decades predictably created a bubble that has meant overleveraged companies going down with half-completed projects and customers losing money. Barring a surprise on the upside last quarter, the economy is sputtering. The government is now planning to hoover up real estate inventory to take some supply off the market and support the prices for some time. But that will mean more investment from the government. Instead of rebalancing the economy, China seems to have again ended up with an investment heavy model with the capacity they have built up in the green-tech sector. Almost two-thirds or more of the global capacity of EVs, solar cells, wind turbines, and EV batteries is now with China. The US is no longer an accessible market. The EU isn't sure whether to follow the US suit. The political pressures are no different in EU countries and it is likely some of them will make EV imports from China restrictive to protect their own automotive industry. Emerging markets like India, the Philippines or Indonesia aren’t going to open up to China easily. Maybe some of the EU or emerging market countries will agree to Chinese companies setting up local production capacity. But that won't help with the capacity already built (and continuing) in China. So, the question is where will China go with this overcapacity? Russia, Hungary and some African client states aren’t large enough markets. Instead of rebalancing, it looks like it is going to be in a deeper hole of wasted capacity and overinvestment. The familiar sceptre of the ‘lost decade’ of Japan in the 90s looms over China if it continues down this path. It is difficult to see Xi stepping back from a confrontation and finding ways to de-escalate the trade wars. There is a misplaced sense of being a victim of the US policies (shared with Russia) and an inflated view that their model of growth is better which will get in the way of any real breakthrough. And the worse China does on the economic front, the greater will be the desire to act politically to demonstrate strength to its domestic constituency. This can only go from bad to worse.

Economic nationalism, de-globalisation, nativism and populism seem to be the dominant and somewhat irreversible trends around the world at this moment. There’s a rising insecure China with a belief in its inevitable destiny of being the global superpower taking on an aging, bumbling superpower that won’t back down nevertheless. It is always a risk to generalise from a few events and draw a bigger picture to fit the narrative. But this is how the 1930s must have felt like.

Global Policy Watch #2: A Singapore Summer

Global issues relevant to India

— Pranay Kotasthane

In the iconic TV Series Mungerilal Ke Haseen Sapne (directed by Prakash Jha), the lead character slips into reverie every episode, lost in a world where his day-to-day life has been substantially upgraded. Many chief ministers have employed these Mungerilal-esque superpowers, dreaming of transforming their capitals into another Singapore: SM Krishna, Arvind Kejriwal, Sheila Dixit—the list is way too long.

It’s easy to dismiss such dreams, as I have done above. I instinctively scoff at casual conversations that contrast India’s development journey with Singapore because the scale doesn’t compare, and the initial conditions are vastly different. Moreover, direct comparisons can also commit the fault of ‘isomorphic mimicry’, as Shruti Rajagopalan and Alex Tabarrok have explained in this classic paper.

While emulation isn’t advisable, it’s quite telling that so many Indian leaders have sought inspiration from Singapore. Perhaps, it’s because Indian cities share base commonalities with Singapore that leading cities in the West don’t. For instance, Singapore, too, is not neatly laid out like a Cadbury dairy milk chocolate, with blocks demarcated by perpendicular roads. Next, the tropical climate necessitates a lot more roadside trees not usually found in great other cities located further north. Finally, a colonial experience dotted by remnant imperial structures is another thing that Indian cities share with Singapore.

And yet, unlike our cities, Singapore actually works. The tap water is potable, the public transport is excellent, the differently abled can move around the city, children can be seen travelling alone on buses and metros, and the street lights remain switched on at night!

As you can infer, I spent the last few days in Singapore. This post is a travelogue compiling observations that might strike a public policy enthusiast from India. This post is strictly anecdotal, and I’ll be happy to learn from your reflections about the place.

The first thing that struck me was the large number of public and private construction projects. My previous mental model of cities was that construction would plateau beyond a GDP per capita threshold, the erstwhile city centre would degrade in livability, and the new construction activity would shift to the periphery. After all, that’s what has happened with many cities in India and in the West. And so, I was pleasantly surprised that even a city-state with a GDP per capita of $82,000 had more metro lines, underpasses, and high-rises to build in the core areas.

Coincidentally, this was also a week when the city-state swore in only its fourth prime minister. One would have thought that this would be a major event with traffic diversions, congratulatory posters, and political roadshows. But that wasn’t the case at all. Perhaps, things would change when Singapore elects a party other than the PAP, which has overpowered its competitors since independence. But for now, apart from some low-key events and a few television interviews, there wasn’t anything visibly remarkable.

Another noticeable aspect was the way import dependence was communicated publicly. As an island city-state, Singapore has no agricultural sector to speak of (<1% of its GDP). There aren’t any substantial reserves of industrial raw materials either. The natural gas used for electricity production is entirely imported. More than 40 per cent of the water is also imported. And yet, Singapore became a developed country by utilising the benefits that globalisation offered. It focused on value-added services and manufacturing, making raw material imports an ally in its growth.

One would ordinarily expect import dependence projected as a strategic vulnerability in government communications. In contrast, I was surprised to see a public advertisement for a new metro line proudly announcing that it was deploying brakes from Germany, displays from Japan, and some other components from France and the Czech Republic, with the rolling stock being assembled at Qingdao in China. The messaging was explicitly about creating an excellent public transport facility by buying the best the world has to offer. Rare, isn’t it?

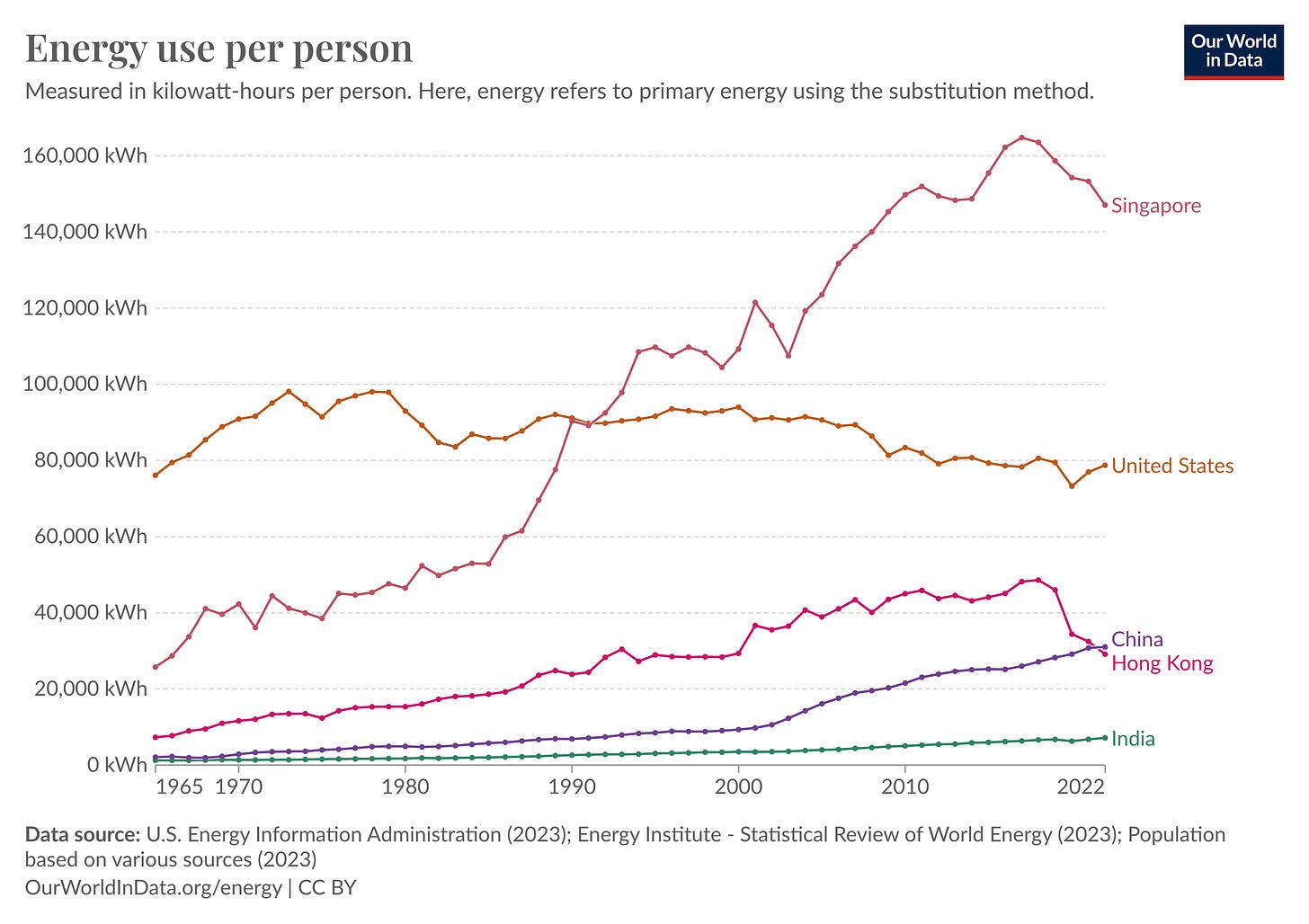

Next, no Indian traveller will fail to notice the high energy intensity of the economy. Lee Kuan Yew famously called air conditioning one of the building blocks of Singapore’s success, and one can see the remnants of that approach everywhere in Singapore. Even open tourist spaces have gigantic fans and coolers, of the kind I have never seen in India. Check out the Our World in Data chart below for evidence. Living in the tropics without air conditioners and coolers is not a battle worth fighting.

A related aspect is the use of disposable plastic carrier bags; they are everywhere. Most plastic waste is incinerated or goes into a landfill on another island, but there wasn’t any moralising around the use of plastic.

Singapore also seems to have adopted a pragmatic approach to climate change. Even though news reports tell you that nearly a fifth of the personal vehicles sold last year were EVs, the increasing taxes on vehicles means that it amounts to a small change over a large base. While about 6000 EVs were sold in 2023, hybrid vehicles accounted for over half the vehicles sold. Overall, the proportion of these new energy vehicles is quite small as the number of existing personal vehicles on the road is in excess of 500 thousand. For an island nation, the lack of climate change doomerism came as a pleasant surprise to me.

That’s about it. I came back with a better appreciation of why Singapore inspires many Indians. If for nothing else, one should visit it if only to focus on the immense work that remains to be done in our cities.

Of course, the leverage point for transformation is to rehaul city governance in India. It’s no surprise that Lee Kuan Yew sharply dismissed Mumbai’s aspirations to become another Singapore thus:

“If Mumbai has to become like Singapore it must become a separate province/state. It is what China has done to develop its cities.”

While creating more centralised union territories might not be feasible or desirable, more fiscal and administrative decentralisation is a necessary pre-condition for improving the quality of life in our cities.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] Check out our puliyabaazi on the ever-relevant Rawls-Nozick puliyabaazi.

[Essay] The attacks on Indian students in Kyrgyzstan highlight the need for scaling up our existing medical colleges. Read our linked essay on the policyWTF that makes our medical colleges underdeliver.

The "Chinese Checkers" piece was very well written, very balanced. It brings out the risks (to themselves) and practical problems in both America and China's approaches. In America's case, an upcoming election makes the policy making for optics-only, outcomes be damned. While China doesn't face that "problem of democracies", it runs the risk that its policies don't encounter public feedback, unless things go horribly wrong for too long... by which time, of course, the damage is done.

I do feel China has the upper hand here mostly because the rest of the world cannot replace China as the producer of goods. Or even if they can, it will take a long time to happen - not the timeframe that America hopes for.

Pranay, keen to hear your view on the implications of US tariffs on China and China’s likely retaliation on Indian trade balances given some of the manufacturing incentives that GOI has provided for. Thanks.