This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

PS: If you enjoy listening instead of reading, we have this edition available as an audio narration courtesy the good folks at Ad-Auris. If you have any feedback, please send it to us.

India Policy Watch #1: Consumption And The Fable Of Bees

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

‘The pandemic has shown us what is truly important in our lives.’

‘We learnt to go slow and consume only that we need during the lockdown. That’s one lesson we should follow beyond the pandemic.’

‘The earth is healing as the pandemic has forced us to slow down our lives and reduce our greed.’

Every couple of weeks I come across a column that argues on similar lines as above since the pandemic began. I guess we have a great desire to search for a silver lining in the bleakest of scenarios. But this is exactly the kind of silver lining we should avoid. The idea we learn to reduce consumption so the earth can sustain our load doesn’t have any underlying logic. Worse, such reduction will harm the vulnerable and the poor the most. But, hey, good intentions are all that matter, right?

Any discussion on consumption as a vice takes me back to Mandeville and his work ‘The Fable of Bees’ which has a deserving claim of being among the most provocative and counter-intuitive texts of all time. Published in the early 18th century, it’s alternative title, Private Vices, Public(k) Benefits establishes its central thesis upfront. The book is in three parts. The first part is a poem, The Grumbling Hive, which is followed by an essay discussing the poem. The book concludes with an essay An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue that lays out his defence of vice. This essay, as we will soon see, is a proto-text for different schools of economic and moral philosophy that emerged during and after the age of enlightenment.

The Wages Of Virtue

The Grumbling Hive is a simple poem of uncertain literary merit. There’s a hive of bees that live in ‘luxury and ease’ while giving virtue, moderation and restraint a short shift. Instead of being happy with this prosperity, the bees question their lack of morality and wonder (or grumble) if there wasn’t a more honest way to lead their lives. Some kind of divine power grants them their wish and their hearts are filled with virtue now. This turn to an ethical hive however comes at the cost of prosperity.

Ease was a vice now, temperance a virtue and the industry that emerged from the bees competing with one another disappeared since the virtuous bees didn’t bother any further with competition. This lack of industry meant a fall in prosperity. Many thousand bees lost their lives, and society started collapsing. The bees weren’t deterred. They flew into a hollow tree that suited their new lifestyle of restraint. They were content being poor but honest.

Mandeville questions the social benefit of this trade-off.

What good is this virtuous life which keeps everyone poor?

This leads him to make the almost blasphemous claim that vice is good so long as it is within bounds of justice. Not just that he also bats for people as a resource. People are not a burden for society.

This was incendiary material then. And I guess, even now. He wrote:

So Vice is beneficial found, When it’s by Justice lopt and bound;

Nay, where the People would be great, As necessary to the State,

As Hunger is to make ’em eat.

And after having set the Thames on fire, he concludes the poem with these famous lines:

Bare Virtue can’t make Nations live In Splendor;

they, that would revive A Golden Age,

must be as free, For Acorns, as for Honesty.

With this, Mandeville earned his lifelong notoriety as a libertine of dubious morality. It didn’t bother him and his later defence of thievery and prostitution as public good suggests it possibly fuelled his desire to be more outrageous.

Private Vice, Public Benefit

In his essay ‘An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue’, Mandeville explains the paradox of private vice and public benefit further. Mandeville makes three key arguments:

A virtuous act is one that’s unselfish and driven by reason. Acts that are selfish and involve raw passions were vices. Mandeville goes about looking for virtuous acts in society and draws a blank. However, he finds there are acts beneficial to the society that don’t qualify as virtues. He concludes individuals might pursue their self-interest (vice) but on an aggregated basis this might be creating a societal good. For example, members of a society might quarrel among each other pursuing their interest, but that quarrel generates employment for lawyers, clerks and judges. If they were to turn virtuous, this public benefit would disappear.

The natural state of man (the term used in the text which we will use here) was to be selfish. The individual was a ‘fallen man’ who was selfish and sought pleasure only for himself. This vice was the foundation of the society and all social virtues emerged from self-interest. Vice is good. To Mandeville, virtue was a state of denial of this natural state.

Even virtue that man displays is rooted in vice. A man acts with virtue for two reasons –either to satisfy his ego (vanity) of being seen as virtuous by the society or to not offend the ego of his peers. This is a facade to cover the underlying greed or selfish motives that give him private pleasure. These days we might call it virtue signalling.

This cynical take on man and society didn’t earn him friends. The act of calling virtue a facade was unacceptable in a society whose foundation was the Christian notion of virtue. The idea that a human couldn’t do a virtuous act without self-denial negated the concept of a religious man being a superior person who could rise above primal passions. There were multiple attacks on The Fable of Bees from moral and political philosophers of the time.

Yet the text survived for two reasons. One, in its belief that the society is held together by individual acts of self-interest of many and not by some kind of faith in the divine, it was the first attempt at separating social science from the clutches of theology. This was already achieved in natural sciences with scientists like Galileo, Copernicus and Newton challenging religious orthodoxies through the scientific method. The time was ripe for questioning the role of religion in social sciences too. Two, there was something liberating about a text that didn’t speak about how humans should be. Instead, it was a realist’s view of how humans behave in nature and that behaviour at an aggregated level produces social benefits. This was a powerful insight that advocated individual liberty.

The Long Shadow Of The Fable

The Fable of Bees served as inspiration for a wide range of philosophers over the course of the next two centuries. Hume agreed with the basic premise of Mandeville that the sense of morality or virtuousness in a man occurs only in a community or a society through aggregated acts. Hobbes drew from Mandeville on self-interest being the primary motivation for human action. Adam Smith was inspired by the notion of aggregated self-interest producing social good though he disagreed with Mandeville by bringing in the role of sympathy. He also thought vanity alone wasn’t the reason people acted with virtue. There was a desire for true glory too. As Smith wrote in The Theory of Moral Sentiments:

“It is the great fallacy of Dr. Mandeville's book to represent every passion as wholly vicious, which is so in any degree and in any direction. It is thus that he treats everything as vanity which has any reference, either to what are, or to what ought to be the sentiments of others: and it is by means of this sophistry, that he establishes his favourite conclusion, that private vices are public benefits.”

Yet Smith accepts there is a kernel of truth in Mandeville’s core assertion:

“But how destructive soever this system may appear, it could never have imposed upon so great a number of persons, nor have occasioned so general an alarm among those who are the friends of better principles, had it not in some respects bordered upon the truth.” (emphasis ours)

While the fable of bees influenced Smith and his methodological individualism, it also left a mark on Rousseau and the French collectivists who followed him. Rousseau agreed with Mandeville on the lack of social or public-spiritedness in man in the natural state. However, Rousseau introduced ‘pity’ or a “natural repugnance at seeing any other sensible being and particularly any of our own species, suffer pain or death” as natural sentiment within a man. This pity overrode self-interest and became the reason for other virtues.

It isn’t too difficult to see how Mandeville’s philosophy became the founding text for the economic theory based on the primacy of individual liberty and limited intervention of the state. If individual acts of self-interest could lead to social good, what was the need for any intervention by anyone? This was the argument of Friedrich von Hayek who took the fable of bees as the first text that advocated ‘spontaneous order’. He wrote:

“It was through asking how things would have developed if no deliberate actions of legislation had ever interfered that successively all the problems of social and particularly economic theory emerged. There can be little question that the author to whom more than any other this is due was Bernard Mandeville.”

In a similar vein, Ludwig von Mises (Hayek’s peer from the Austrian school) explained, in Theory and History (1957):

“Only in the Age of Enlightenment did some eminent philosophers . . .inaugurate a new social philosophy . . . They looked upon human events from the point of view of the ends aimed at by acting men, instead of from the point of view of the plans ascribed to God or nature . . .

“Bernard Mandeville in his Fable of the Bees tried to discredit this doctrine. He pointed out that self-interest and the desire for material well-being, commonly stigmatized as vices, are in fact the incentives whose operation makes for welfare, prosperity, and civilization.”

While Hayek and Mises were crediting Mandeville for being the first to articulate spontaneous order, their great intellectual rival, Keynes, was finding merits in the fable of bees too. Keynes’ Paradox of Thrift is the intellectual progeny of the Private Vice, Public Virtue paradox:

“For although the amount of his own saving is unlikely to have any significant influence on his own income, the reactions of the amount of his consumption on the incomes of others makes it impossible for all individuals simultaneously to save any given sums. Every such attempt to save more by reducing consumption will so affect incomes that the attempt necessarily defeats itself. It is, of course, just as impossible for the community as a whole to save less than the amount of current investment, since the attempt to do so will necessarily raise incomes to a level at which the sums which individuals choose to save add up to a figure exactly equal to the amount of investment.”

The state could get itself out of a recession by stimulating demand and increasing consumption while it could dig itself into a bigger hole by reducing consumption. Keynes credits Mandeville’s work in his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money for highlighting consumption (aggregate demand) as the principal engine for economic prosperity.

It is possible Mandeville wasn’t aware of the profound implications of his fable when he wrote it. He was possibly baiting the hypocrites of the society of his time who hectored others to live in virtue while committing vices themselves. It is also likely he was being ridiculous for the sake of infamy since he seemed to enjoy riling up people. But given his influence on the entire spectrum of philosophical and economic thought – from individualism to collectivism and from statism to laissez faire – I’m inclined to side with Adam Smith.

Mandeville’s fable borders on a fundamental truth – private vices may lead to public good.

A Framework a Week: A COVID-19 Vaccine Deployment Strategy for India

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

What should India’s approach be to deploying a COVID-19 vaccine? Once a vaccine candidate passes all clinical trial stages, the sequencing problem is non-trivial for a country of India’s size and income levels.

Consider this: India’s rather successful and extensive Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP) vaccinates about 2.9 crore mothers (and 2.6 crore infants) annually whereas the COVID-19 vaccine has to reach nearly 100 crore people as soon as possible — a problem 30 times bigger than what the UIP manages.

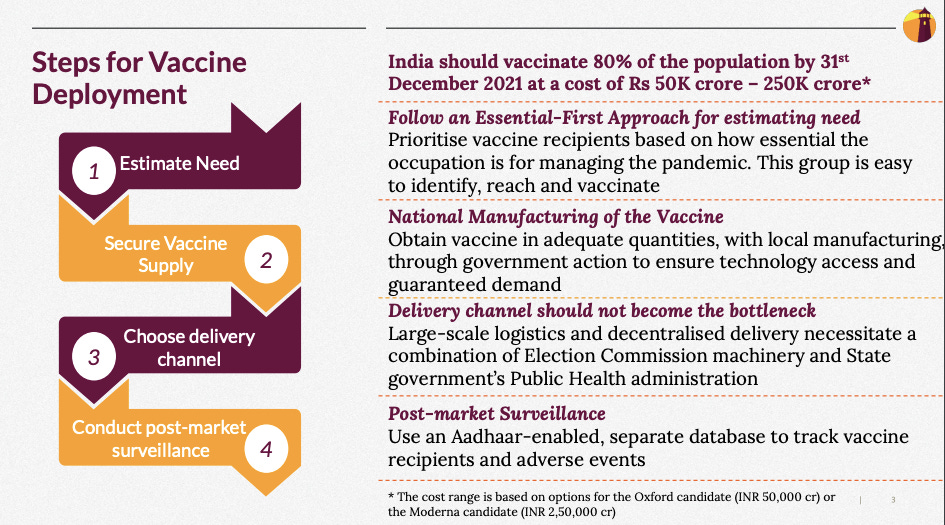

Led by my colleague Shambhavi Naik, we have a reaseach document out that develops a framework for vaccine deployment. It breaks down the challenge into four parts:

(Source: Shambhavi Naik et al, A COVID-19 vaccine deployment strategy for India. Takshashila Discussion SlideDoc, September 2020)

Estimate Need: Initially, prioritise a really small set of recipients initially based on how essential the service they provide is for managing the pandemic. Once that’s out of the way, randomisation works better than sequencing recipients based on age, comorbidity prevalence, or other such demographic indicators.

Secure Vaccine Supply: At our current production capacity, vaccinating 80% of the population will require 20 months. Which means India will need to source vaccines from other companies/countries and incentivise increased manufacturing in India. A transparent model contract specifying terms of technology transfer and manufacturing partnerships to build manufacturer and public confidence.

Choose Delivery Channel: Use the Election Commission of India machinery to get the vaccine booths to the people in a mission mode operation. The state governments’ public health administration will coordinate the vaccine administration.

Track Vaccine Distribution: A separate database, enabled by Aadhaar and/or election ink as an identifier, to track vaccine distribution and adverse events.

Do give the document a read and send in your suggestions. This problem needs all hands on deck.

Not a PolicyWTF: The Art of Letting Go

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Pranay Kotasthane

In this section, we are on the lookout for egregious policies. Such policies are not difficult to find. Very rarely though, the reverse happens. Governments spring up a surprise on us by bringing in pro-market reforms.

Here are two such cases from the recent past. Neither can be classified as a policy success. They are at best first steps in the right direction, requiring further work.

EV Minus Battery

On August 12, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways notified that state governments allow registration of electric vehicles without pre-fitted batteries. Since batteries make up 30-40% of an EV’s cost, this move is intended to bring down up-front costs for consumers.

This is a positive move. Unbundling the battery from the vehicle creates new market opportunities. A consumer can potentially register an EV from a vehicle manufacturer but get the vehicle battery from an energy management company. Energy management companies can come up with new models for both battery swapping or for the charging infrastructure.

Of course, this move has made the incumbent vehicle makers unhappy as their own battery manufacturing plans now face a new challenge. Nevertheless, a pro-market policy is often an anti-incumbent one.

One bottleneck remains. Batteries are taxed at 18% GST while EVs are taxed at 5% GST. This creates an inverted duty structure (explained in edition#50) that will generate huge GST refund claims — some fraudulent, others genuine. This must be fixed by taxing both batteries and EVs at the same rate.

Governments prefer overregulation. But this move is an example of dismantling regulation and enabling markets. For governing technologies under low state capacity, stepping back instead of overdetermining rules is a better approach. Market conditions should inform regulation, not the other way around.

The Corporatisation of Ordnance Factory Board

If you thought defence PSUs such as HAL and BEL are underperforming, you haven’t met Ordnance Factories (OFs). These 41 factories form ‘the largest and oldest departmentally run industrial organisation in India’ (Indian Defence Industry: An Agenda for Making in India, page 20). Together they employ more than 80,000 people.

In 2013-14, OFs had sales of more than eleven thousand crores and yet being a departmentally run organisation, they do not have to follow commercial accounting practices, and do not have to maintain balance sheets and P&L statements. Even their barebones annual reports are classified and hence not open to public scrutiny. How convenient.

Not surprisingly, OFs have failed to deliver. The government has now constituted an Empowered Group of Ministers (EGoM) to begin corporatisation — a process that will make these OFs into one or more defence PSUs such HAL. Even though these DPSUs will remain a wholly-owned entity of the Ministry of Defence, corporatisation will make these factories quasi-independent of government and allow them to focus on business goals such as profits and return on investment. With their own budgets and balance sheets, their performance (or the lack of it) will be out in the open.

Corporatisation was first proposed by the Kelkar Committee in 2005. Fifteen years down the line, it seems to be gathering some steam. Nevertheless, as our DPSUs demonstrate, corporatisation is but a first step towards a modern defence industrial base. Going further, non-performing OFs should be shut down or the stake in them should be divested.

India Policy Watch #2: A Fog Of Information

— RSJ

We have made the point in an earlier edition about the perils of scanning sectoral data or select high-frequency indicators to arrive at any conclusion about economic recovery in India. The pandemic is still raging with daily case count on an upward trend, supply chains aren’t fully restored, and the consumers aren’t confident of stepping out of their homes and spending. The pandemic and the lockdown were idiosyncratic events and we should accept the uncertainty that comes with it. Yet we seem to be keen on highlighting narrow slivers of data and drawing conclusions from them.

Kidding Ourselves?

Take this news item that suggests “signs of a pickup that augurs well for manufacturing activity”. Our exports have gone up by 13 per cent and the railway freight loading is up by 10 per cent. That’s great news till you realise the period of comparison is a week! That is, we are comparing data for the week of Sep 1-8 this year to the previous year. It is difficult to draw any conclusion when you compare a random weekly data with the previous year in normal times. It makes no sense to do it in these times.

For instance, the railway freight loading could be up because the trucking and logistics companies might still be coming to terms with lockdown disruptions, working capital drying up and absence of drivers who might have gone back to their homes. Till you see a complete picture of the movement of goods across all modes of transport, it is difficult to conclude manufacturing activity is up. A similar case can be made for exports where a single week can’t suggest a trend. But you have the country’s #1 daily newspaper showcasing this as an instance of green shoots of recovery.

Or there’s this news item that talks up the auto sector. There’s been a 15-20 per cent growth in auto sales during the 15-day festive period of Ganesh Chaturthi and Onam in the two states of Maharashtra and Kerala. This data is then used to suggest a strong recovery could be on cards in the oncoming festive season. This despite an industry official making it clear these numbers aren’t comparable because of the floods in Kerala during the same time last year that had severely impacted sales.

Sobering Reality

Then we have this news which indicates we might have lost 21 million salaried jobs in the five months of the pandemic. As Mahesh Vyas, MD & CEO, CMIE, writes:

“An estimated 21 million salaried employees have lost their jobs by the end of August. There were 86 million salaried jobs in India during 2019-20. In August 2020, their count was down to 65 million. The deficit of 21 million jobs is the biggest among all types of employment. About 4.8 million salaried jobs were lost in July and then in August, another 3.3 million jobs were gone. These job losses cannot be confined to only of the support staff among salaried employees. The damage is likely to be deeper, among industrial workers and also white-collar workers.”

Here we have a research agency that has a long track record of measuring employment data suggesting we might have lost almost a quarter of salaried jobs during the pandemic. Now even this is data for only five months, but you might agree with the long-term view of the author that salaried jobs once lost are more difficult to replace. So, this is a trend that should worry the policymakers.

In the same article, Vyas makes another important point about the stagnation of salaried jobs and the rise of ‘entrepreneurs’ who don’t employ anyone:

“In 2016-17, employment in entrepreneurship accounted for 13 per cent of total employment. This proportion rose to 15 per cent in 2017-18, then 17 per cent in 2018-19 and 19 per cent in 2019-20. This sustained increase in entrepreneurship in India has not led to a rise in salaried jobs. The count of entrepreneurs has risen from 54 million in 2016-17 to 78 million in 2019-20. During the same period the count of salaried employees has remained stable at 86 million. It is counterintuitive to see a rise in entrepreneurship but not a corresponding increase in salaried jobs.

Part of the reason for this is that most of these entrepreneurs are self-employed who do not employ others. Implicitly, they are mostly very small entrepreneurs. The government has propounded the idea that people should be job providers rather than job seekers. This objective seems to be succeeding but not entirely in ways that was intended.

Entrepreneurship is often a desperate escape from unemployment rather than an initiative to create jobs.”

Act With Confidence, Plan For The Worst

We understand all data is political in the best of times. It is used by partisans and critics of any government to build narratives that suit them. However, the normal expectation is that beyond the political rhetoric the policymakers know which data to use to draft a course of action. We fear this might not be true in these times.

First, the data from various sources isn’t indicating a definite trend about the economy. This inability to have any kind of predictive certainty about the extent of contraction, tax collections or the true picture of fiscal deficit makes decision making difficult. This is a difficult time to be a policymaker. This gets compounded by the government being keen to talk up a V-shaped recovery to an extent where there are fears it has started believing its own message about the economy is beginning to touch pre-COVID levels. There’s merit in highlighting feel-good news to build consumer confidence and spur consumption. We get that. We just hope the government is able to make out the difference between its own hype and reality. Often it is not easy to make this out.

We have written in our earlier editions that a second ‘real’ stimulus has to be launched before the end of Q2. The extent of contraction in Q1, the impact on the informal economy that’s not fully measured yet, the fall in salaried jobs and the reluctance among consumers to spend make a fiscal stimulus necessary to get the economic engine going again. Also, a significant stimulus announcement in Q2 will be a good indicator of the government not drinking its own kool-aid about a V-shaped recovery.

The government and the PM continue to enjoy very high approval ratings. The people are convinced about their intentions. There’s no taint of corruption or policy paralysis on it. These are ideal grounds for the government to take people into confidence about the challenges the economy faces and the sacrifices the people need to make in the short-term as we begin the long road to recovery. This clarity will be welcome. The current fog of information doesn’t help our cause.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Normany Barry on ‘The Tradition of Spontaneous Order’ where he traces the origin of this philosophical thought.

[Article] A Business Standard editorial on why the government should listen to advice that it doesn’t consider politically ‘reliable’.

[Paper] Elinor Ostrom’s integrative paper A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Social-Ecological Systems continues to remain relevant.

[Book] Indian Defence Industry by Laxman Kumar Behera gives a good overview of India’s defence industrial base.

That’s all for this weekend. Read and share.

Share this post