#324 Bottlenecks

Restarting Reforms, The Long Delays from an Act to Rules, and Framing the Taiwan Contingency Problem

If you’re reading this newsletter, it’s fair to say you’re already in the business of anticipating the unintended. If you’d like to sharpen that instinct with formal training in policy thinking and analysis, the 12-week Graduate Certificate in Public Policy (Advanced Public Policy specialisation) might be just what you’re looking for.

Readers of Anticipating the Unintended are eligible for a 10 per cent fee waiver. How to claim it: In the application form, under the question “How did you hear about the GCPP?”, select “Other” and type: I want to learn to anticipate the unintended

Table of Contents

India Policy Watch #1: Making DeReg Happen

Insights on current policy issues in India

—RSJ

The Bihar elections that had promised a close fight between the two big coalitions and a new party as a joker in the pack ended up as a damp squib. The results were eye-poppingly one-sided with the BJP ending up with an almost 90 per cent strike rate in the seats they contested, an unprecedented performance in any elections in the history of free India.

This is the third state election after Haryana and Maharashtra in which almost every pollster got it wrong by a wide margin. There have been allegations swirling around voter list malpractices, about the special intensive revision (SIR) of electoral rolls and the ease with which incumbent governments could announce and execute on welfare schemes in the run-up to elections across these states.

While it can be argued that the current opposition has been remarkably incompetent in raising issues and sustaining them for long to make an impact on the electorate nationally, it wasn’t doing badly in drawing crowds in each of these state elections. Democracy is undermined when the sanctity of the electoral process is repeatedly questioned. The usual response of this being sour grapes is fine coming from the ruling party, but it cannot be the view of the Election Commission of India (ECI).

I’m not sure of how credible the ‘vote chori’ allegations of the opposition are, but either way, it is for the ECI to respond to them with clarity and conviction to nip the whispers around its credibility in the bud. Three times is too much of a coincidence otherwise. I fear we are possibly only a couple of elections away from when the opposition starts to boycott elections in India. That would be terrible for its people and for India’s credibility in the world.

Anyway, with the Bihar elections over, the focus of the Union government appears to have shifted to legislation and reforms in the forthcoming winter session of Parliament. This week, the government announced the implementation of four new codes on labour that had been approved by the parliament about five years back but were on ice since. The four codes, namely, Wages, Industrial Relations, Social Security and Occupational Safety, will replace 29 labour laws that have been around for decades, with the new codes reflecting the new reality of employment in India. The changes are a good mix of providing a fair deal to workers while securing their futures and lightening the compliance burden for establishments. At least that’s how it is on paper.

So we have new norms and definitions for universal minimum wage that now covers all employees in both organised and unorganised sectors (in comparison to the earlier Act that only applied to scheduled employment covering about 30 percent of workers), a common definition of wages (basic salary to be at least 50 percent of total CTC), and formalisation of all appointment letters with details of wages and social security included.

These are good measures with workers' welfare in mind, but they will increase the surface area of compliance across sectors. Unless designed right with self-disclosures and digitisation as the cornerstone, this could possibly lead to more labour law inspectors running amok, a greater burden of compliance for the informal sectors and more opportunities for rent seeking.

The more important elements in the four codes coming into effect are what’s been eliminated from the old laws. A lot of offences that are not considered criminal in nature and yet invite imprisonment have been decriminalised. They have been replaced with a 30-day notice for compliance and monetary penalties that are compoundable for a fine only. Similarly, the threshold for getting approval for retrenchment or closure has been raised from 100 to 300 workers, and the threshold for a factory has been raised from 20 to 40 workers. These are useful bits of decongestion.

Labour law reforms are critical for a flourishing manufacturing sector in India. The Compliance 3.0 report released by TeamLease RegTech earlier this year had some mind-blowing statistics around regulatory cholesterol that make running a business in India a high-risk adventure sport. For instance, there are over 25,000 compliance norms across sectors in India that have imprisonment clauses for violations. Of these, more than 80 per cent are in the purview of the states. Significantly, over two-thirds of such imprisonment clauses are accounted for by the current labour laws. So, as much as these new codes will decriminalise many such compliances, the real reform opportunity, like many other things, rests with the states.

I’m not sure if there is a concerted drive to unclog the regulatory cholesterol within states, especially those that have the “double-engine sarkaar”. Starting these off in a few states will hopefully stoke competitive federalism and get others to follow suit. Hopefully, these four Codes will get the states rethinking their own set of compliances.

Anyway, these are kind of basic reforms that have almost no downside and they should have been done a lot earlier. Hopefully, these will lead to some real improvement in the ease of doing business for small and mid-sized enterprises. My guess is that anywhere up to one per cent of GDP growth is shackled by the sheer number of laws that an enterprise has to comply with to run its business in India. Even freeing up half these constraints will be a huge positive.

Labour laws apart, there are at least three other key bills lined up for the winter session that are of long-term consequence. Of special interest is the Repealing and Amendment Bill, which is aimed at repealing about 120 obsolete laws overseen by the Union government, which will be taken off the statute book. The couple of rounds of Jan Vishwas bills have managed to knock off only about 300 laws so far. Possibly, a Bill passed in the parliament will speed up the repealing process for the others.

The other Bill is the National Highways (Amendment) Bill, aimed at faster and transparent land acquisition for national highways. While the rate of addition of a kilometre of national highway has picked up pace and key national highways have improved significantly, we still have a significant deficit on road linkages between smaller towns and cities. The ambitious Gati Shakti national plan and the freight corridor plan will need to be sped up if India were to bring down significantly its road logistics costs of ₹11/km per tonne transported.

Lastly, there is also the Atomic Energy Bill that intends to open up nuclear power generation to the private sector. For long, we have maintained that given India’s energy dependency, the social and environmental costs of coal-generated power, the demand for reliable power by industry and the huge costs of transition to green energy, it will be prudent for India to look at nuclear power as an option. The risks of nuclear power are inflated because of the newsworthy nature of disasters in the past, but on balance, it is among the safest and economical sources of power. A calibrated opening up of the sector with a comprehensive set of safeguards will help the economy in the long run.

I’m not sure if these reforms (including the GST rationalisation) were always on the agenda in the course of this year. I suspect the failure to close the US trade deal, coupled with the rhetoric around it from Trump, the emerging view among investors that brackets India among ‘AI losers’ and some hard geopolitical lessons learnt after Operation Sindoor, have put these reforms on a fast track. The old notion that India reforms only when faced with a crisis still holds true, I guess. We shouldn’t be complaining.

Addendum

— Pranay Kotasthane

Simplifying our complex labour regulations is an important milestone in India’s economic journey. RSJ has already explained the stakes involved. Tangentially, what we, as students of Indian public policy, should note is the long gestation period between a law’s enactment and its implementation.

Take the case of these labour code reforms. The Ministry of Labour and Employment introduced four bills to consolidate 29 central laws way back in 2019. One of them (Code on Wages, 2019) was passed by Parliament that year itself. The other three were referred to the Standing Committee on Labour. Once the Standing Committee submitted its report on all three, the government proposed new versions of these bills in September 2020. Eventually, all four bills had been approved by the two houses of the parliament by that month.

Since these bills involve subjects in the Concurrent List of the Constitution, it was desirable to have the states frame their draft rules in alignment with the new Acts. That understandably took some time. But it’s not done and dusted yet. Even after making the laws “effective” earlier this week, there’s still some way to go. The announcement says that “the Government will likewise engage the public and stakeholders in the framing of the corresponding rules, regulations, schemes, etc. under the Codes.” This means once the Union government notifies new rules under these acts, it might take another couple of years for all states to frame new rules in line with these changes. That makes it a mighty eight-year timeframe between the approval of the Parliament and its implementation.

Even if we were to grant the government some leeway due to the complexities involved with labour reforms, its record on some other areas is not great either. Earlier last week, the long-pending rules for the Digital Personal Data Protection Act of 2023 were finally notified, making this law fully operational EIGHT years after the Union government first constituted a committee on this topic.

Other areas haven’t been this lucky either. Consider the case of the Indian armed forces’ integrated theatre commands. The post of the Chief of Defence Staff was created by the Union cabinet in 2019, and one of its express objectives was “Facilitation of restructuring of Military Commands for optimal utilisation of resources by bringing about jointness in operations, including through establishment of joint/theatre commands.” Six years later, inter-service frictions continue to be aired in the open, vitiating the atmosphere even as implementation of the theatrerisation remains further away.

We aren’t talking about the difficulty of converting vague promises into concrete policies here. It’s that even after the government or Parliament has given its express approval, it has taken several years for these reforms to become a reality. And that’s when we have had the same ruling coalition for over eleven years.

Now, it’s understandable that a democratic system has checks and balances, which, by design, should make the passage of major laws difficult. But it’s also a reminder to observers of Indian public policy that the community advocating policy reforms within governments is small. It can’t pursue all desirable reforms at once; prioritisation is necessary.

Undoing bad laws takes way longer than operating in a fresh new domain. That’s traditionally why governments have relied on crises to shave off months from a typical law’s lifespan. But using the crisis route requires an unvarnished assessment of India’s current situation, without which, we will continue to be in the slow lane.

PS: Arun Shourie once characterised the slow pace of reforms using this memorable line from Akbar Allahabadi: plateon ki awaaz toh aati hai, par khaana nahi aa raha (one can hear plates clattering, but there is no food to be had).

Matsyanyaaya: The Taiwan Contingency

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

—Pranay Kotasthane

Finally, I have my own version of that famous software dependency meme by XKDR, and it looks like this:

So many of our techno-economic expectations for the near future rely on one major assumption: Taiwan’s continued political status quo.

I have written earlier that China won’t invade Taiwan for semiconductors. Rather, it will be the Chinese Communist Party’s political aims and compulsions that might drive it to attempt something as risky as blockading or invading Taiwan.

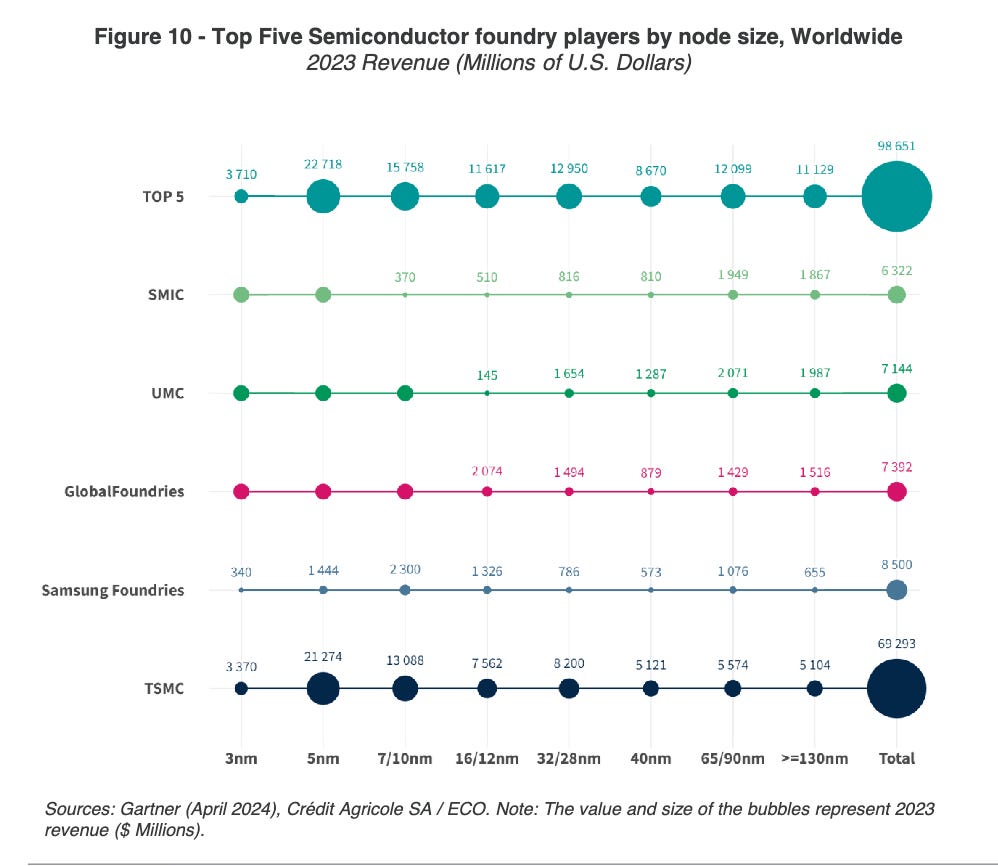

Whatever the motivation, the effects of such an action will reverberate across the world through the semiconductor domain. To understand why, take a look at this chart:

In this chart of the top five foundry players across the various nodes, TSMC and UMC are Taiwanese. Now, TSMC is well-known for its over 90 per cent dominance in the advanced nodes, but this chart shows that Taiwanese foundries are also dominant players in mature node segments (>=28nm).

Thus, a blockade or invasion of Taiwan will cause problems to all downstream OEMs, from cars to laptops, and from phones to medical devices. A Bloomberg Economics model estimates a 5 per cent global GDP loss in year one in the blockade scenario, and a jaw-dropping 10 per cent global GDP loss in the invasion scenario.

The good news is that some diversification is underway. Nearly 100 new foundries are being constructed across the world, the majority of them are in the mature node segment. Even in the advanced nodes segment, TSMC itself is starting factories in Japan and the US, and I am sure there are contingency plans to airlift key TSMC personnel out of Taiwan if the invasion happens.

The TSMC Chairman Mark Liu has said on record that if China were to take over Taiwan, it would find TSMC’s facilities unusable. He asserts their secret ingredient is human capital and real-time international collaboration with companies for materials, software, hardware, and know-how. Nevertheless, shifting the production process to another foundry, even if by the same company, is an operationally and technologically complex task that can take months. Substituting Taiwan’s prowess, even with Taiwanese talent, might take atleast a couple of years.

This is the scenario that Indian policymakers should focus on with regard to Taiwan: how should we prepare our firms upstream and downstream of Taiwanese foundries in case of an invasion or blockade? We need a contingency plan involving banks, investors, insurance companies, and governments. We will discuss some ideas on this question in a subsequent edition.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Manish Sabharwal lists some specifics of the labour code reforms:

“The new labour codes reduce 1,228 sections to 480, 1,436 rules to 351, 84 registers to 8, 31 returns to 1, 8 registers to 1, and 4 licences to 1. It decriminalises 65 sections that weaponise thousands of compliances. It expands social security to gig and unorganised workers, removes unfair restrictions on women, and enables portability of benefits for inter-state migrant workers. It reduces corruption by tackling multiple definitions of wages/employee/worker, mandatory physical records, multiple licences given for short durations, prosecution without notice, a non-randomised inspection regime, no time limitation on past case inquiry, the power to re-open past cases suo motu, and an unreasonable EPFO-assessed appeal deposit amount of 75 per cent.

The four labour codes are not perfect; there should be only one. But they represent a huge leap in making India a better habitat for good job creation.” [Indian Express]

[Video] Federation for Economic Development has an inspiring conversation with the promoters of Shahi Exports, one of India’s largest apparel exporters, and an employer of 1 lakh+ people, of which nearly 70 per cent are women.

[Report] The OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Report 2025 is out. It is a comprehensive review of recent geopolitical developments in the context of science and technology.

[Podcast] We have a Puliyabaazi on the fantastic insights from the Report of the Committee on Emotional Integration (1962). Sample these lines from the report:

1.14 Any student of the cultural history of India will be struck by the fact that, along with tolerance, the power of assimilation is one of its strongest characteristics. Early in her history the Aryan and non-Aryan inhabitants had come together. The Aryan element in the composite culture that emerged as a result, may have been strong, but the non-Aryan contribution was no less important. To quote an example—Ganesa finds no mention among the Vedic gods and has no Vedic mantras specifically associated with him. Distinctly

non-Aryan but Indian in origin, we first meet him as a Vinayaka, an evil spirit, but he has gradually worked his way up, so that today, with a very few exceptions, no Hindu, religious ceremony is complete without his having a place of honour in it…. Such intermingling in the sphere of religion (where people are generally very conservative) is an index to the extent to which assimilation had proceeded.

Minor nitpicking: the 90% strike rate isn't unprecedented. I had dug into this in the past year and, barring small states and small parties, it was TDP which first recorded such a strike rate in Andhra's 2024 assembly elections (winning 135 out of 144 seats contested). At the time of its win, there was an argument that state results were becoming one-sided, a reflection of a polarised electorate. The polarisation isn't argued to be along religious or some such lines but simply about electorates beginning to vote en masse for one coalition/major party.