#56 The Emotional Atyaachaar of Aatmanirbharta

The missing demand-side economic package, back to import substitution, fait accompli land grabs, and good narratives

This newsletter is really a weekly public policy thought-letter. While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought-letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. It seeks to answer just one question: how do I think about a particular public policy problem/solution?

India Policy Watch: What Next For The Economy?

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

In the third week of May, the government rolled out a ₹20 trillion economic package to mitigate the risks of COVID-19 pandemic. The package was a mix of fiscal and monetary stimulus for the short-term with a few important structural reforms included whose impact could play out in the long-term. The critics of package felt it was anaemic on measures to stimulate demand and didn’t do enough to restore consumer confidence to spend.

The government had a different view. They argued the supply-side measures will save firms from going under, protect jobs and, eventually, lead to demand revival. Since then the COVID-19 case count has kept its exponential march on and we have had multiple localised lockdowns in most of our urban centres. The virus has spread to most large states and lifestyles and household consumption patterns have undergone changes that impact the Indian consumption story. Ten weeks later, it is useful to ask if we have a better sense of how things are unfolding.

The Package That Wasn’t A Package

We had raised three issues across multiple editions of this newsletter about the ‘aatmanirbhar’ economic package:

The government’s decision to focus on supply-side interventions could have several reasons. One, it didn’t want to blow a hole through the fiscal deficit targets which could lead to ratings downgrades and collateral damages. Since the pandemic was a global phenomenon, we felt the government was overestimating the ratings agencies and their impact. Two, we were almost sure the government would come out with a fiscal relief and stimulus package before Q2 (ending September) as the extent of demand destruction becomes evident. Three, a strong state is a prerequisite for a targeted and efficient implementation of fiscal stimulus measures. We felt the supply side emphasis was a tacit acknowledgement by the state that it lacks confidence in its administrative machinery.

We were worried about how we track the success of the measures announced by the government. More specifically, we were interested in the central claim that these measures will revive demand indirectly. Our concern was in the absence of an agreed-upon metrics to track, we will be treated to ‘cherry-picking’ of data to rival peak season in the Anatolian orchards.

We felt ‘aatmanirbhar’ was too open-ended a term to interpret. We cautioned, despite the assurances offered by the PM and the FM, it would devolve into import substitution and a protective trade regime across non-strategic goods which would be a net negative for India.

In this section of the newsletter, we will focus on the first two issues highlighted above. The third issue is discussed in the next section.

Supply Side Can’t Do All The Heavy Lifting

The government has continued with its stand on supply-side measures being adequate to tackle the crisis. The credit facilities that were offered to MSMEs and other larger corporates haven’t been fully utilised. They aren’t keen on increasing their debt until they are sure of the demand picking up. What has instead happened is a classic case of unintended consequences.

The credit facilities have been used by two kinds of firms. One, those who are already in a strong financial position and have used this to accumulate ‘dry powder’ for future at low rates. Two, on the other extreme, by firms who were in a bad shape even before the pandemic and are using its cover to prolong their lives. The spectre of zombie firms that plagued the Japanese economy for the last three decades is quite real. The deserving ‘middle’ who would have been helped by a demand stimulus has been squeezed. The role of the market in efficient allocation of resources that leads to creative destruction has been compromised.

The recent statements by the CEA have been perplexing. In one of his recent interviews, he made three points that helped to understand the government’s thinking now. One, the government is seeing green shoots of demand recovery with the data from GST to road toll collections being shown as evidence. Senior officials in finance ministry claimed we will see a V-shaped recovery in the coming months. Two, the CEA claimed a fiscal stimulus will work best when customer confidence is back. In his view, this will happen only after a vaccine is ready. So, it is best to launch the fiscal stimulus then. Now is the wrong time since consumers will park the stimulus money in the banks instead of spending them. Three, the CEA brought up the Indian policy response during the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and how it led to high inflation and a currency crisis in 2012. The government wants to avoid a repeat.

There’s a lot that doesn’t add up in this narrative. First, the points on green shoots of recovery don’t reconcile with the government waiting for consumer sentiments to revive only after a vaccine is developed. If we are already seeing green shoots and the finance ministry is talking about a V-shaped recovery, why wait till a vaccine is developed to deliver a fiscal stimulus? The right time should be now. Only one of these two statements can be correct.

Consumption is as much about sentiment as it is about actually having the money to buy. A stimulus is, therefore, a signal by the government that can improve consumer sentiment. Waiting till the vaccine is developed is a wrong signal and will continue to dampen sentiments.

Also, we aren’t sure if the right lessons of our policy response to the GFC are being learnt. It wasn’t about the timing of our response then which was quite appropriate. It was how long we continued with a loose fiscal policy that hurt us. In The Lost Decade (2008-18), Puja Mehra chronicles how Pranab Mukherjee, who was the FM then, continued with the stimulus way longer than it was needed:

“Over the next three years, Mukherjee, the dirigiste finance minister, hiked allocations for social-sector spends, ignoring the revenue position, the expanding fiscal deficit and the economy’s capacity for absorbing the fund releases productively. The budget for 2008–09 presented in February 2008, months ahead of Lehman’s collapse, had projected a fiscal deficit of 2.5 per cent and a revenue deficit of 1 per cent. A year later, presenting the Interim Budget in February 2009, Mukherjee told a shocked Lok Sabha that the fiscal deficit had ballooned to 6 per cent of GDP and the revenue deficit had widened to 4.4 per cent. The actuals came out later in line with these projections. The fiscal stimulus overdose, Chidambaram conceded in 2013, overheated the economy and stoked inflation. The effects played out over time.

Arvind Virmani, chief economic adviser till 2009-end, prepared and submitted a road map for ending the fiscal stimulus before leaving the post to assume charge as India’s representative to the IMF in Washington. It lay about unattended, gathering dust, ignored or forgotten. ‘When a recovery is evident, reverse the stimulus,’ this exit strategy proposed. Virmani’s second recommendation was, ‘Resume reforms then for removing bottlenecks to sustain the growth recovery.’

…..Even after the rebound in the economy, the stimulus was allowed to go on. The overstimulation soon set inflation on fire.”

What’s The Real Consumption Story?

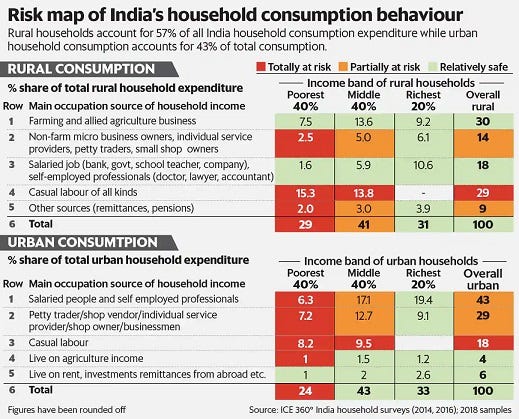

The contention that we will soon see a V-shaped recovery needs greater scrutiny. This requires a better understanding of the household consumption behaviour in India. In April, Rama Bijapurkar and Dr Rajesh Shukla had co-authored an article in Mint that suggested only about 58 per cent of household consumption will come through assuming a good monsoon and a robust rural economy. The rest will take a severe hit because of the pandemic. This article didn’t envisage further lockdowns and the absence of a fiscal stimulus while arriving at this conclusion. The chart below (from the Mint article) lays out the risk map of India’s household consumption behaviour.

(Source: Livemint)

It is difficult to see how a V-shaped recover can happen without providing a stimulus to those who are most at risk. In rural households, the increase in enrollment in MGNREGA at a minimum wage is not a substitute for the more remunerative jobs many of these workers had in urban areas. The duration of support through MGNREGA is also going to be limited. The rural casual labourer and the non-farm small business owners will not spur demand because their incomes will either have remained the same or reduced.

In urban areas, we will suggest caution on over-reading the data from GST, highway toll collections, a few corporate earnings or increase in volumes of e-commerce or e-grocery firms. Let’s take a few typical examples of consumption patterns of the middle and richer income bands of urban households (accounting for 76 per cent of urban consumption). Before pandemic, a family bought vegetables and fruits from their local vendor in the typical vegetable ‘bazaar’. The vegetable markets are crowded locations. They have either been shut during the lockdowns or have seen very few footfalls. A lot of vendors have shut shop too because of lack of demand. So, the family has shifted to an online grocer now. This family either buys the same amount online that it bought from their offline vegetable vendor. Or, it could be buying a lesser quantity because its income has taken a hit during the pandemic. However, for the online grocer, this will show up as an increase in revenues. Similar shifts from informal to the formal sector could play out in other areas like food (small restaurants and hawkers to packaged food), clothes and other consumables.

A Shift With Consequences

We need to understand this shift and factor it in while gathering evidence for policy decisions. There are three ways this could play out.

First, this shift will result in growth for firms in the formal economy like the example of the e-grocer or the packaged food manufacturer cited above. This will show up in quarterly results, GST collections and highway tolls because the formal sector is more widely networked. Any decision made using only such data will fall into the familiar partial equilibrium analysis trap. There could be a larger demand destruction happening in the informal sector at the same time.

Second, the informal sector gets accounted for in India’s GDP in an interesting way. Simply put, a baseline for informal sector contribution is arrived at once every five years and it then tracks the growth rates of the formal sector in the interim. This works fine when growth or a shock in the economy impacts both formal and informal sector equally. However, in case of a shock like this (or demonetisation) where the formal and informal sectors decouple, this assumption is fraught with the risk of overestimating the GDP. Pronab Sen, former principal economic advisor and chief statistician of the government wrote this perceptive paper, The Covid-19 Shock: Learning from the Past, Addressing the Present, last month, that outlined how a similar decoupling had played during and after monetisation:

“What was surprising was that despite palpable damage to significant parts of the Indian economy, GDP growth in 2017-18 was estimated at 8.2% - the highest since 2012-13. Unfortunately, this was an optical (or more correctly, a statistical) illusion. Apart from agriculture, Indian GDP estimates are primarily based on data from the organised sector, which is extrapolated to cover the informal and SME sectors as well.9 Since, as has been already explained, the formal sector actually gained at the expense of the informal and the small, this procedure grossly overestimated the growth rate. Thus, while the higher production of corporates got recorded, the presumptive negative growth of the SME sector was completely ignored.

The denouement came in mid-2018, when GDP growth started slipping steadily. It has now been more than six quarters that the growth rate has declined quarter by quarter from 8% to 4.5%. The damage done to the informal and SME sectors had now started showing up in corporate results as well, through its effect on incomes and demand.”

Third, the shrinkage in real consumption and the nature of recovery will not be visible by looking at the usual data sources. It is vital for us to look at non-conventional sources and surrogates for informal sector performance to arrive at a true picture of the economy. The Financial Times has put together a recovery tracker (free to read till August 2) using a mix of various datasets that might give a more accurate understanding of where an economy stands. Take a look at it. India is not recovering well at all. The government should use similar trackers. It is easy to fall into the trap of confirmation bias and look for data that fits it. That will lead to late diagnosis and greater pain for the economy down the road. It can be avoided if we remain sceptical of the recovery trends.

The anticipated demand revival through supply-side interventions hasn’t yet materialised. It will be useful to relook at this assumption instead of searching for data to validate it. The government should rethink its position on a fiscal stimulus only after a vaccine has been developed. That might be too late.

PolicyWTFs: The Aatmnirbhar Way to Become An Economic Superpower

This section looks at egregious public policies. Policies that make you go: WTF, Did that really happen?

— Raghu Sanjaylal Jaitley

We had more than a few concerns when ‘aatmanirbhar’ Bharat became the showpiece of our economic package to combat the pandemic. The skirmish at the LAC with China and our somewhat misguided choice to respond to them on economic terms deepened our concerns. The Overton window had shifted on protectionist instincts in these months.

Despite the assurances of the FM and the Commerce minister that self-reliance isn’t about closing ourselves to the world but dealing with it on our own terms, we had apprehensions. And we had good reasons.

One, we felt this was shorthand for import substitution and higher trade barriers. We feared it won’t be restricted to a handful of strategic sectors or only to imports from China.

Two, the government is the biggest buyer of goods and services in the industry. We run a big state. It was likely that the government would modify its procurement norms to encourage local content. The regulations on local content across a variety of goods and services would be difficult to arrive at and it will lead to more discretionary powers with the officials of the state. Public procurement in India isn’t a model of transparency in its current state.

Three, the supply chains were already disrupted during the pandemic leading to pockets of scarcity and price rise. Any knee-jerk response to restrict imports could mean companies scrambling to find substitutes which might be scarce and costlier. This could prolong supply disruptions and delay demand recovery in the absence of a stimulus. We also suspected most Indian industrialists would support the protectionist policies in a throwback to the role they played in the heydays of ‘license-permit-quota raj’. It is easier to manage the government than market forces.

We Told You So

Over the last couple of months, the state has defined ‘aatmanirbhar’ for us through its revealed preferences. Yesterday, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) announced restrictions on import of colour TVs rolling the clock back to more than two decades. Nostalgia is good but not of this kind. Any importer of colour TVs will now have to seek a license from DGFT. Another news report suggests the government plans to increase tariffs and trade barriers on 300 imported products:

“The government document showed feedback had been sought from various Indian ministries to arrive at the list of around 300 products..”

India has increased duties on more than 3,600 tariff lines covering products from sectors such as textiles and electronics since 2014, the document added.

Yesterday, we came across this notification from the ministry of commerce regarding the revision to Public Procurement Order, 2017. This was released on June 4 but we missed it. It is fair to say there were too many PolicyWTFs to keep track.

Now, public procurement guideline is an old favourite of ours. We have written about it in the context of Bachchan starrer Trishul a few months back. There have been significant changes to the government procurement policy based on this notification:

Each supplier will be categorised into either Class-1 local supplier, Class-2 local supplier or non-local supplier based on the percentage of local content in their end product or service. Those with more than 50 per cent local content will be Class-1, between 20 per cent to 50 per cent will be Class-2 and the rest will be non-local suppliers.

Each nodal ministry or department will have to now assess the domestic manufacturing capabilities, supplier base and available capacity. This is to ensure they are able to assess the local capacity and competition for a good or service.

Once the nodal ministry is convinced local capacity exists, only Class-1 suppliers will be eligible for the bids.

In case local capacity doesn’t exist, the L1 (the lowest-priced) bidder will be checked for local content. In case they are Class-1, the bid will be awarded to them. In case the L1 bidder isn’t a Class-1 supplier, the closest priced Class-1 bidder will be invited to match the L1 price up to a limit called the ‘margin of purchase preference’. This is set at 20 per cent or above in the notification. It can’t be lowered below this without approval from the minister.

In simple words, a Class-1 local supplier has the option of bidding at 20 per cent higher than the price of L1 bidder. If they do so, they win the bid. There’s an additional wrinkle on whether the contract is ‘divisible’ or not, but you get the gist. The Class 1 local supplier gets an option to win the bid away from L1 while being priced 20 per cent higher.

There are other interesting bits in the notification. In case there are countries who bar Indian companies from bids in their domestic markets, the ministry plans a quid pro quo. Also, there are multiple provisions to fine and debar suppliers, random audits and other usual list of definitions in the notification.

Hum Kisi Se Kam Nahin

Looking at the above notification, it is difficult to believe we aren’t headed towards an import substitution regime for all goods and services. These are textbook examples of such a regime. We have written on multiple occasions why this is a bad idea. Now that we have a concrete proposal, it is useful to examine why it is so. We also know there’s a sizeable section of the society that believes our path to prosperity lies in being aatmanirbhar. There are emotional arguments made on why we can’t trust Indians to make products for which we have technical know-how available. Like an industry leader was quoted as saying:

"India can emerge as the next hub for manufacturing TV not only for the Indian markets but also for the global market. This step is definitely in the right direction and will help in creating a global hub, which we want to be and it also helps to create a strong ecosystem for manufacturing of the products.”

Or like the FM once said – can’t we make a Ganesha idol from clay?

Repeating History?

We won’t repeat the economic arguments again. You can read it in the link above or here. We have our history of following such policies through the decades of 60s-80s. The slow growth rate of that era, the dismal quality of our products and the long waiting time for products is still fresh in some of our memories. Maybe the new generation wants a taste of it. There’s no reason why this time the outcome will be different.

We should make our firms competitive to take on suppliers in global markets. Instead, we are giving them crutches in the domestic market. The only way to win is for our firms to benchmark themselves to global standards and exceed them. It would have made some sense if the Class-1 local supplier is given the mandate to match the L1 rates and quality standards within 2 years of winning the bid or some clause of the kind that spurs global benchmarking. An uneven domestic playing field is just fooling ourselves about our capabilities.

Also, like we feared the guidelines further increase the load on state capacity and its discretionary powers. Nodal departments will decide on whether there’s sufficient capacity in a particular sector for it to qualify for local content guidelines. There is no objective measure to arrive at this decision. Instead of competing with a foreign firm, domestic firms will lobby with the department to classify their sector differently and eliminate foreign competition. The determination of the percentage of local content and its audit and inspection will open up another window of rent-seeking among officials.

There are other practical challenges. It is possible for a supplier to certify they will have more than 50 per cent of local content at the start of the work. But it is anybody’s guess if they struggle to keep local content above 50 per cent during the course of the work. The supplier might be debarred from future bids but will the current project be stopped and rebid? Since the notification comes into effect from August, it is quite likely there will be an escalation of government costs because the local supplier will take time to become cost-effective in many sectors. This is an additional strain on an already bad fiscal situation during this year. Lastly, it is difficult to understand why we have included all goods, services and works under these guidelines. We have limited availability of technical talent, trained resources and capital. Instead of producing world-beating champions in a few selected sectors, we will end up producing a large number of mediocre suppliers who will compete locally and end up being subscale. They will deliver low returns on capital employed and stall labour productivity and wage increases.

There doesn’t seem to be strong economic voices advising the government about the long-term implications of such moves. Or, maybe, the government knows about it but continues to pursue this course for short-term gains and for the inherent emotional appeal of such steps. Either way, we can’t do much about it except crying ourselves hoarse.

The government and the people want to repeat history. Who are we to get in the way?

PS: If you want to know more about the repercussions of economic ‘nationalism’, this episode of the Hindi podcast Lights, Camera, Azaadi featuring Pranay might interest you.

A Framework a Week: What Makes a Good Narrative?

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

Narratives are central to public policies because we think in terms of stories. No matter how good our public policy proposal might be, constructing a powerful story around it is equally important.

Specifically, three reasons make narratives important. One, building and riding narratives decides whether the “time has come for an idea”. Two, a good narrative makes the policy recommendation easy, even superfluous. And three, politics itself is a contestation for narrative superiority and dominance as opposed to ideological dominance.

Stories, narrative arcs, images, symbols, numbers, and causes are some building blocks for creating powerful narratives. But what makes a narrative stand out?

This framework by Marc Saxer in his paper Practical Guide to Transformative Change Making lists five criteria:

A good change narrative has five elements:

Threat: What is the danger of continuing with the status quo?

Hope: The vision for a better future where the interests of key constituencies converge. The vision is the lens through which key constituencies imagine the future and interpret the situation today. The vision needs to be vague enough to allow different groups to project onto it, yet concrete enough to alter the calculation of risks versus opportunities.

Opportunity: The change narrative must credibly explain how this vision can become a reality. Game Changers explain how long term, structural drivers (e.g. technological innovation, demographics, geopolitics, connectivity, trade, education etc.) will create a window of opportunity to achieve the alternative vision.

Confidence: Facts need to be framed in such a way that makes them emotionally accessible and cognitively tangible through metaphors evoking shared historical experiences, myths, legends, norms and values. Historical experiences, for instance, suggest that what has been done before, can be done again.

Ethical Imperative: Why the doable is the right thing to do?

While the aim of this framework is to effect transformative change in public policies, it also explains why even some self-defeating policies of Indian governments enjoy widespread support. Hint: they are couched in powerful narratives.

Take the ‘aatmanirbhar’ Bharat narrative for example. It satisfies all five criteria. Let’s see how: the danger of continuing with the status quo is that our strategic adversary, the PRC, can ‘cripple’ Indian markets and industries if it wishes to. This is the threat. The hope is a vague vision of a self-reliant India. The global backlash against China’s arrogance provides the opportunity. The long-standing “sone ki chidiya” myth provides the confidence — if it could be done before, it can be done now. Finally, framed as an essential precondition for economic progress, aatmanirbhar also becomes an ethical imperative, not just an instrumental approach.

Once this well-crafted narrative is put into motion, the government can execute even counterproductive policies under its garb. And so we have import duties on TVs and bans on apps that enjoy popular support.

The lesson from this framework is that the kinds of things we write about in this newsletter — unintended consequences, cost-benefit analysis, economic reasoning — are necessary but not sufficient in countering terrible policies. What’s needed are counter-narratives that build on the five elements described above. Good policies need not just good evidence but also good stories.

Matsyanyaaya: Possession is Nine-tenths of the Law

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

It’s now increasingly clear that the PRC has executed a land grab and it has no plans of returning to status quo ante. Meanwhile, the land grab has come as a bolt from the blue for many in India. Unable to understand the PRC’s worldview, quite a few respected strategic commentators have adopted a defensive stance: was it India that provoked the PRC? Was it August 5, 2019? Or is it the India—US partnership? Or is it a road being built near the LAC?

There are two main problems with this line of thinking. One, it ignores the PRC’s conduct with its other neighbours. Two, the India-focused view ignores how common fait accompli land grabs are.

It is the second point that we are focusing on in this edition. The conventional thinking in international relations is that territorial gains are made either by a full-scale war or by coercing another state to give up its claims. The third route — executing a land grab without an explicit threat i.e. fait accompli — is imagined as an unlikely tool of statecraft given how problematic it is.

Except it isn’t rare. Dan Altman’s research note By Fait Accompli, Not Coercion: How States Wrest Territory from Their Adversaries finds that between 1918 and 2016, 112 land grabs seized territory by fait accompli. In contrast, only 13 publicly declared coercive threats elicited cessions of territory. Further, he observes:

“Conquest no longer goes hand in hand with warfare as part of a brute force strategy. Land grabs attempting to take smaller territories without provoking war as part of a fait accompli strategy are now the predominant form of territorial conquest. Conquest has not gone away, but rather has become smaller, more targeted, and less violent”.

The note also finds that fait accompli land grabs in the past have failed to secure lasting gains — nearly 25 per cent of them were followed by retaliatory land grabs whereas 27 per cent resulted in wars, some of which reversed land grabs.

This finding has important consequences for Indian statecraft. Given that it has territorial disputes with two hostile neighbours, attempts at fait accompli land grabs are here to stay. Also given that some of the border areas are uninhabited and inhospitable even for troops, foiling such land grabs through extensive patrolling might not always be possible. Instead, we need to reimagine military means that can deter land grabs in the future.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] John Lee writes in The Diplomat about the global war for 5G heating up.

[Article] There’s a new Ipsos-Mori survey on ‘What worries the world’. Coronavirus is #1. But unemployment isn’t far behind.

[Interview] Viral Acharya hasn’t stopped talking about the government’s U-turn on banking reforms. Here he’s in an interview with Ira Duggal on the BloombergQuint.

[Book] The Dutch historian Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is an uplifting read. It argues that humans are not so bad after all.

That’s all for this weekend. Read and share.

If you like the kind of things this newsletter talks about, consider taking up the Takshashila Institution’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy (GCPP) course. It’s fully online and meant for working professionals. Applications for the August 2020 cohort are now open. For more details, check here.