India Policy Watch #1: Nayi Umar Ki Purani Fasal

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

PM Modi, in an address to the nation at 9 AM on Friday, repealed the three farm laws that had been pushed through in the parliament without any debate more than a year ago. Choosing the occasion of Guru Nanak Jayanti, the PM said his government was unable to convince the farmers about the benefits of the laws. We have written a few times earlier about our view on farm reforms and these three laws in particular (we have linked them at various places in this edition). This repeal might well mean farm sector reforms are dead and buried for a decade, if not more. This is going to be terrible for Indian agriculture in the long term. That apart, as public policy watchers, there are few important lessons to take away from the entire episode.

Before we get onto what we learnt, a short summary of where we stand on the farm laws. Firstly, on any measure of outcomes, Indian agriculture is in a terrible state. Things are so bad that you can safely say there's no change that can make it any worse. In edition #70 (Section: No Looking Back on Agricultural Reforms), we wrote:

The dismal state of Indian agriculture bears no repetition. The farm income growth has been stagnant for the last 6 years. The small and marginal farmers who constitute 86 per cent of India’s peasantry barely make a living out of farming with average per capita annual income below Rs. 100,000. About 45 farmers die by suicide on an average every day. The Food Corporation of India (FCI) buys the produce at the minimum support prices (MSP) from the mandis and distributes it at a subsidised rate through the public distribution system (PDS). This subsidy bill has grown to an unmanageable level.

The FCI borrows from National Small Savings Funds (NSSF) to keep its operations going. It is estimated this loan will rise to Rs. 3.5 lakh crores in FY ‘21 from Rs. 2.5 lakh crores in FY ’20. Millions of ordinary Indians trust NSSF with their lifelong savings. It is anybody’s guess when FCI will be able to pay back NSSF. If this appears like a giant Ponzi scheme, that’s what it is. The food grains stocked at FCI are at an all-time high but there’s no market mechanism for its distribution when people needed it the most during the pandemic. They had to wait for the largesse of the state for the stored grains to reach them. This is a broken system. Even if you set out to create a dysfunctional system, you’d have struggled to reach here.

Who in their right minds would want this structure to continue? Who has it helped except entrenched cartels and a few dynasties of ‘farmer leaders’ who have built a system of patronage?

Agriculture contributes to about 17 per cent of India’s GDP and supports almost half of its 1.4 billion people. With that kind of skew, it is no surprise then that they live in poverty that’s comparable to sub-Saharan Africa. It will be useful to frame a simple model of agriculture productivity to appreciate the issues here. In modern states, land is a finite resource for most owners. Land cannot be annexed from others nor can you squat on a piece of land, mix your labour with the soil and then claim ownership of it. This means landholdings continue to get divided and smaller as they get passed onto the next generation. Smaller holdings are less productive and this sets in a cycle of impoverishment. Almost every nation that transitioned from a low-income economy to a middle income or beyond learnt this truth the hard way.

At The Root Of It

There are two simultaneous moves that an economy must make to solve this. First, enable the creation of a huge number of low or medium-skilled jobs that can attract labour to move out of agriculture. And second, increase productivity for those remaining in the farm sector to increase their incomes. To put it charitably, we have had moderate success doing the first. The three decades since 1991 have created more non-farm sector jobs than the four before. We could have done more. Much more. But at least we tried.

On the second, we haven’t even done that. Despite the many committees that have diagnosed the problem and recommended specific measures, we have baulked at carrying out any serious agriculture reforms. Things continued to get worse while urban Indians read articles that romanticised the Indian farmer and his sacred relationship with the land. Ironically, while being driven by someone who might have quit farming, preferring to live in urban squalor than dying on his land.

The simple model of farm productivity then focuses on three drivers:

Optimal decision making: Farming is about getting a few key decisions right - when to sow, what seeds to sow, the likely pests, blight or negative weather events that can be predicted and how to insure the downside of things going wrong? Farming is a high-risk venture and getting the many small decisions right is critical. There’s science behind making these decisions and with greater availability of data and better connectivity, the farmers can make better choices.

Mechanisation: This is a no-brainer. A tractor-driven cultivator is about a hundred times more productive than an ox-driven one. Like this, across the farming supply chain, there are multiple opportunities for a machine to replace human labour. This and the use of ammonia-based fertilizers are what drove huge productivity jumps in farms in the western world in the early 20th century.

Logistics: Farm produce is either perishable or vulnerable to infestation and spoilage. The ability to store and move the produce safely between farms and markets have an impact on productivity

Now, for these three levers to be used effectively, there are two necessary conditions - the ability of the farmer to sell their produce freely to anyone and at a price they both agree on. This is important to appreciate. This freedom to choose who to sell to and the role of price as a signal are both important for any producer to work on improving their productivity. Distort this and you take away the incentives from the producers. This is a counterintuitive notion for most people. Our natural intuition is I will be better off if I know what price I will get for my product. So, most of us think fixing a price in advance is good. Unfortunately, this kind of a price cap or a floor, makes things worse as it has been seen in agriculture in India. Deadweight loss is real in most instances. Price is an outcome of millions of voluntary transactions between buyers and suppliers. Like Hayek wrote (see the original article in the HomeWork section of this edition):

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess. The economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate “given” resources—if “given” is taken to mean given to a single mind which deliberately solves the problem set by these “data.” It is rather a problem of how to secure the best use of resources known to any of the members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.

It is a terrible idea to fix prices as history has shown us over and over again. Instead of price caps, the answer to protecting against price fluctuations in any product is the creation of a futures market that provides a mechanism to protect the downside risk for the producers. The farm laws that have been repealed were a major step in going down this path of freedom for farmers. Any other alternative to these reforms must address these fundamental points. Else, it will not solve the productivity challenge in Indian agriculture.

Before moving on to the lessons learnt, there’s one more point I’d like to tackle. A constant refrain I heard from those who opposed these reforms was that it will lead to ‘corporates’ (Ambani and Adani, for example) gaining control of Indian agriculture who will then exploit the farmers and eventually, the consumers with their exploitative terms. There are many things wrong here. The Indians who raise this spectre don’t have any problem with ‘corporates’ in their lives who offer them low priced connectivity, everyday discounts on groceries and vegetables and the general freedom they enjoy to freelance or sell their goods and services to them. But the same logic won’t hold good for farm produce, apparently. The seeds of statism sown in the 60s-70s have such deep roots that anything can be delegitimised in the name of corporate. The right thing to do, of course, is to ensure these reforms are pro-market and not pro-business. Instead, we choose not to do any reforms because we don’t understand the difference.

Moving On

So, what are the lessons we learnt from here?

Firstly, even if the reforms have a sound basis and are consistent with the recommendations of the many committees of the past, it is important to think of both timing and the distributional consequences of those losing out. Like Pranay wrote in episode #90 (Section: Farmers’ Protest):

Any reform that is even remotely seen to impact the MSP gravy train is bound to face opposition from a host of incumbent beneficiaries. One, the farmers growing the 22 crops backed by the MSP. Two, the traders getting a percentage of the MSP. And three, the state governments that make money by charging hefty commissions for the sale of produce at APMCs. None of this is surprising.

That apart, [..] two critiques that merit serious attention: one, the timing of these reforms amidst the worst economic crisis in decades meant that the government needed to align the cognitive maps of those losing out. Two, the government fostered suspicions because the three farm laws said nothing about the impact on the existing procurement price mechanisms.

This has meant real farm sector reforms are dead and buried for the foreseeable future. It is a tragedy. The lesson here is that there can be no policy without politics. And politics itself is hardly about winning at the spectator sport called elections, once every five years, something this dispensation has mastered.

Farmers in the protesting areas were effectively government employees relying on a salary in the form of MSP for producing select grains for over half a century. To make any change to this status quo needed building trust, reaching out to the opposition and the farmer lobbies, and to state governments. The government did none of these before the laws were announced.

Over the next few days, many commentators will use this repeal to repeat that “good economics is not good politics in India”, the actual lesson to be learnt is that policy is downstream of politics. Hubris prevented the government from seeing this point.

Secondly, when faced with genuine criticism of the proposed reforms, there should be a good-faith discussion to improve the proposal. There were a few terrible clauses in the Farm Bill (as is often the case in any Bill) that could have been changed to accommodate the opposing concerns. I wrote about this in edition #94 (Section: Missing Artists in our Polity):

Clauses that can only be called illiberal have seen their way through these laws including those where the executive is given powers to adjudicate with no remedial mechanism to appeal against the decision in civil courts. This won’t stand in any court of law.

…. when confronted with the first signs of protests, the entire playbook of how not to manage protests was put into action. First, the police force was deployed to break the protests. Then the protesters were dismissed as rich farmers or middlemen protecting their turf. Finally, they were branded as Khalistani terrorists and anti-nationals before some mediation was attempted.

Once you have gone down this path, there’s hardly any room for rapprochement. The government and its overzealous narrative machine must shoulder the blame for this one. Though a minor silver lining out of all of this is that there are limits to narrative building even for this government which is adept at it. Despite the many efforts to derail the protests through the media, it continued to thrive.

Thirdly, policy reforms should be a low key affair. It should be done in the back rooms with discussions, drafting and redrafting of clauses and attempts at consensus. You shouldn’t expect to have everyone agree on reforms but doing it in a low key manner takes the sting away from anyone protesting against them. Instead, this government likes its ‘shock and awe’ approach to reforms despite evidence that it rarely works. Also, it is a fact that the protests were concentrated in a few regions of north India around NCR. There were barely any protests in non-BJP ruled states too that were of any consequence. This should have been easy to solve if there were real efforts made early on to use back channels to address the concerns of the farmers of Punjab, Haryana and western UP. But that was not to be. That aside there are other policy tools available to improve various sectors of the economy than a fundamental rewriting of laws. We have written before on how our over reliance on monetary policy and big reforms than using available fiscal policy tools and devolution of powers to states and local bodies is a lost opportunity. That should be the way forward for this government in these partisan times where its good policy proposals will also be opposed.

Fourthly, the subsequent responses to the PM’s announcement are quite revealing. There’s only a very tiny section that’s lamenting the repeal of these laws for what can be called genuine reasons. A vast majority of the supporters of this government and the PM are seething with rage because of other reasons. One, it is difficult to walk back on your publicly stated positions. So, they are using the fig leaf of national security and furthering the narrative about Khalistani elements involved in these protests which isn’t what the PM said. But the other reason for their anger and their rhetorical questions about what next - CAA, Article 370? - is because in a way this repeal allows them to strengthen their myth about how deeply entrenched and powerful the left-liberal ‘enemy’ is and why there should be no letting down of the guards. This is being positioned as some kind of bowing down to the ‘mob’ of leftist malcontents and their technique of using street violence to meet their objectives. This will then be used to tar other protests against bad laws. Never again will we let this happen is the war cry now for them. This is also a useful strawman to forewarn any dilution on other ‘cultural’ issues by the government that are more dear to this lot than any real interest in farm sector reforms. That’s why you see this synchronised outrage against the decision that comes with a holier than thou attitude of see, we can criticise our own side. The running down of the minority protesters as undemocratic will be useful to strengthen majoritarian moves in future in the name of democracy.

Also, there are equally pointless celebrations on the other side of the ideological divide. Apparently, this is a victory of democracy and the role of protests. Really? This is a pyrrhic victory at best for those who were supporting the protests. What next after the repeal? Is there a counter-proposal that actually helps the farm sector? Nothing. And to those who think this will give a fillip to other protests, you must be living in what Aristophanes called cloud cuckoo land. This wasn’t an acknowledgement of protests working in a democracy. This was about improving the odds of winning a few state elections in the coming months. You think that’s democracy working? Then you should accept all other polarising issues that will be used to win elections also as proof of democracy working.

Lastly, what’s the real reason for repeal? If it was about farmers and their protests, it should not have taken a year of protests and many deaths to repeal these laws. And if it was indeed, maybe the cabinet should have joined the farmers at the protest site and repealed the laws that it had passed. Instead, it is the political expediency of winning more seats in the state elections that likely led to this. And that’s a huge disappointment for anyone who believes we can still get long-term structural and factor reforms done in this country.

The ordinary Indian farmer will continue to toil in possibly the most oppressive farming system in the world. Meanwhile, partisans on both sides will continue to milk this for their benefit. Everything will either be a masterstroke or a disaster. Foretold.

Divided by ideology, united by our collective stupidity.

And all we can do is watch and write. But like Auden wrote in his poem, September 1, 1939:

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie

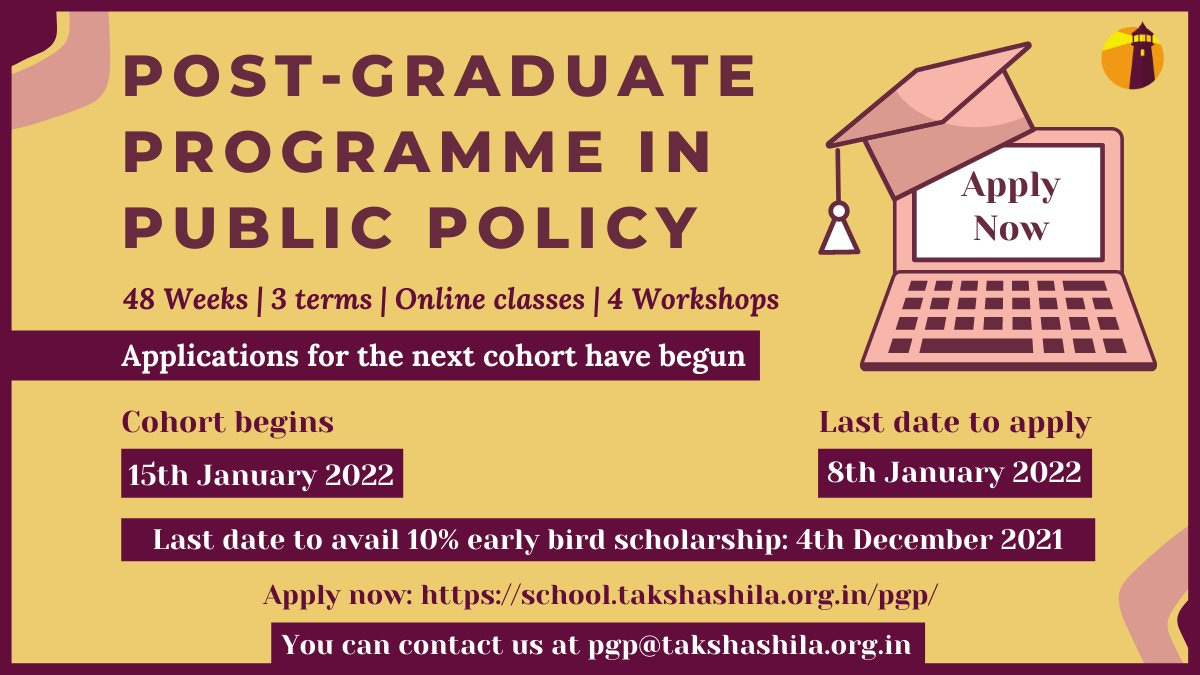

If you find the content here useful, consider taking a deep dive into the world of public policy. Takshashila’s PGP — a 48-week certificate course will allow you to learn public policy analysis from the best practitioners, academics, and teachers. And that too, while you continue to work. In other words, the opportunity costs are low and the benefits are life-changing. Do check out.

India Policy Watch #2: North-South Divergence

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

The sharp difference in the socioeconomic trajectories of states in northern and southern India is a subject of many a discussion. Casual conversations on the topic often end up identifying vague cultural differences as the root cause for this divergence. But if you’re looking for some serious, empirical work on this topic, check out this underrated 2015 book The Paradox of India's North–South Divide by Samuel Paul and Kala Sridhar.

Here are my annotated notes on some counterintuitive points presented in the book.

The Economic Divergence is of Recent Origin

In the book, the North is a shorthand for the four big states in north-central India, Rajasthan, UP, MP and Bihar while the South refers to the old Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka.

First and foremost, the book points out that the economic divergence between the two regions is real and recent. It begins by highlighting that the direction of economic migration in the first three decades after independence was not what it is today. As the authors write:

“Appleby's report on India's public administration in 1953 and 1957 identified UP (and Bihar) as the best governed states in the 1950s. In the first three decades since Independence, a significant number of people from the South went to the northern and western Indian cities in search of jobs. In many lower-level jobs, in both the private and public sector, large numbers of southerners could be found in cities such as Mumbai, Kolkata and Delhi. There was no such migration from the North to the South. For many observers, it was a clear signal that the South had limited employment opportunities, and that its people had lower standards of living, forcing them to go out of their region to improve their lot.”

The rather recent divergence in economic outcomes is in sharp contrast to popular perceptions about the dominant social values in the two regions. For instance, Ambedkar had this to say in 1955 in Thoughts on Linguistic States:

“There is a vast difference between the North and the South. The North is conservative. The South is progressive. The North is superstitious, the South

is rational. The South is educationally forward, the North is educationally backward. The culture of the South is modern. The culture of the North is ancient.”

Either this cultural difference was exaggerated or this factor had only a cursory impact on economic performance, which started diverging only in the late 1980s.

Size vs Density

A common perception in the South is that the North is way too crowded. While that is true in aggregate population terms, the population density figures tell another story. For instance, Kerala’s population density is higher than UP (2011 census). Moreover, the two other big states in the North, Rajasthan and MP are sparsely populated because of the Thar desert and dense forests respectively. The authors in fact speculate that the higher density might have made the compact southern states more governable. But they stop short of advising that northern states be split up into smaller units.

This issue of size has made a comeback in recent months. Historian Ramachandra Guha argued in The Telegraph that the large electoral size of UP hands it a disproportionate and undesirable political influence in the Union. Guha cites the views of both KM Panikkar and BR Ambedkar, who separately came to the conclusion that the large size of UP would crowd out the concerns of the other states.

I am sympathetic to this view. This is probably a less-worse idea than the calls obstructing the use of the latest census figures for delimiting constituencies. However, this idea needs to resonate with the people in different regions of UP. Apart from one half-hearted attempt by the Mayawati government, that does not seem to be the case. In absence of on-ground political champions, arguments from outside will have little effect.

The Role of Human Capital

Differences in human capital investment can have long term effects on economic performance. This is one point of convergence in the writings of Amartya Sen and Milton Friedman (Friedman’s memorandum to GoI in 1955 is linked in the Homework section). This effect also explains the regional disparities in Italy, where the North is far more prosperous than the South, arguably due to the variable adoption of Napoleonic educational reforms between 1801 and 1814!

This seems to be the case in India as well. Regions in the South already had a lead on human development indicators at the time of independence. However, this did not result in immediate economic returns. In fact, the poverty rates of TN were worse than those of UP in the 1970s.

The higher investment in human capital, particularly technical education, in the South finally started showing results when the state got out of the way as a result of liberalisation. The unlocking of human potential needed the locking down of state power over the economy.

Interestingly, the human capital investment in the South had a far greater impact than public spending in the North. The authors find that per capita development spending was higher in the North than in the South in the early decades after Independence. But this changed once the South became richer after liberalisation, allowing the states to claw back a higher portion of the generated income toward development spending.

Roving Bandits vs Stationary Bandits

The higher per capita development spending in the early years of independence in the North did not translate into better public goods provision. Political instability, corruption, and poor law and order conditions meant that the State behaved more like Mancur Olson’s roving bandit. Those in power were in a hurry to run away with the loot. In contrast, the State in the South was akin to Olson’s stationary bandit. Those in power did enrich themselves, but through seeking rents from generating economic value and providing some public goods.

Speculating on the root cause of this difference, the authors argue that social movements in the South strengthened the demand for public goods and in turn led to the growth of education and the spread of entrepreneurship.

Picture Abhi Baaki Hai

By 2021, the economic divergence between the two regions is apparent to most Indians. This has also led to glib assertions of some sort of cultural superiority in the South. To such people, the authors’ cautionary note is worth repeating in full:

“Our reference to the better performance of the South should not be taken to mean that its development outcomes are of the highest order. No writer has made such a claim in the literature. The reference here is only to the relative positions of the regions involved in terms of development. It is not an invitation to the southern states to be complacent, and assume that they have reached a high level of development. India still remains a developing country, and even our better performing states are yet to reach a ‘middle-income country status’.”

Not North vs South but North and South. We are in this together.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Friedrich Hayek’s essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society” in the American Economic Review, 1945. He used the example of the tin market to show how price communicates relevant information to buyers and producers.

[Book] Centre for Civil Society’s compilation on Milton Friedman’s writings on India is a must-read. Friedman’s lucid prose and prescient insights are mind-blowing.

[Podcast] A new Puliyabaazi on the political economy of 1991 reforms.

Share this post