#242 Treading a Tightrope

Farmer Protests in Europe, Inflation Ain't Easy to Predict, the Rise of Populists, and a Shiny New Public Policy Comic Book.

Book Announcement

— Pranay Kotasthane

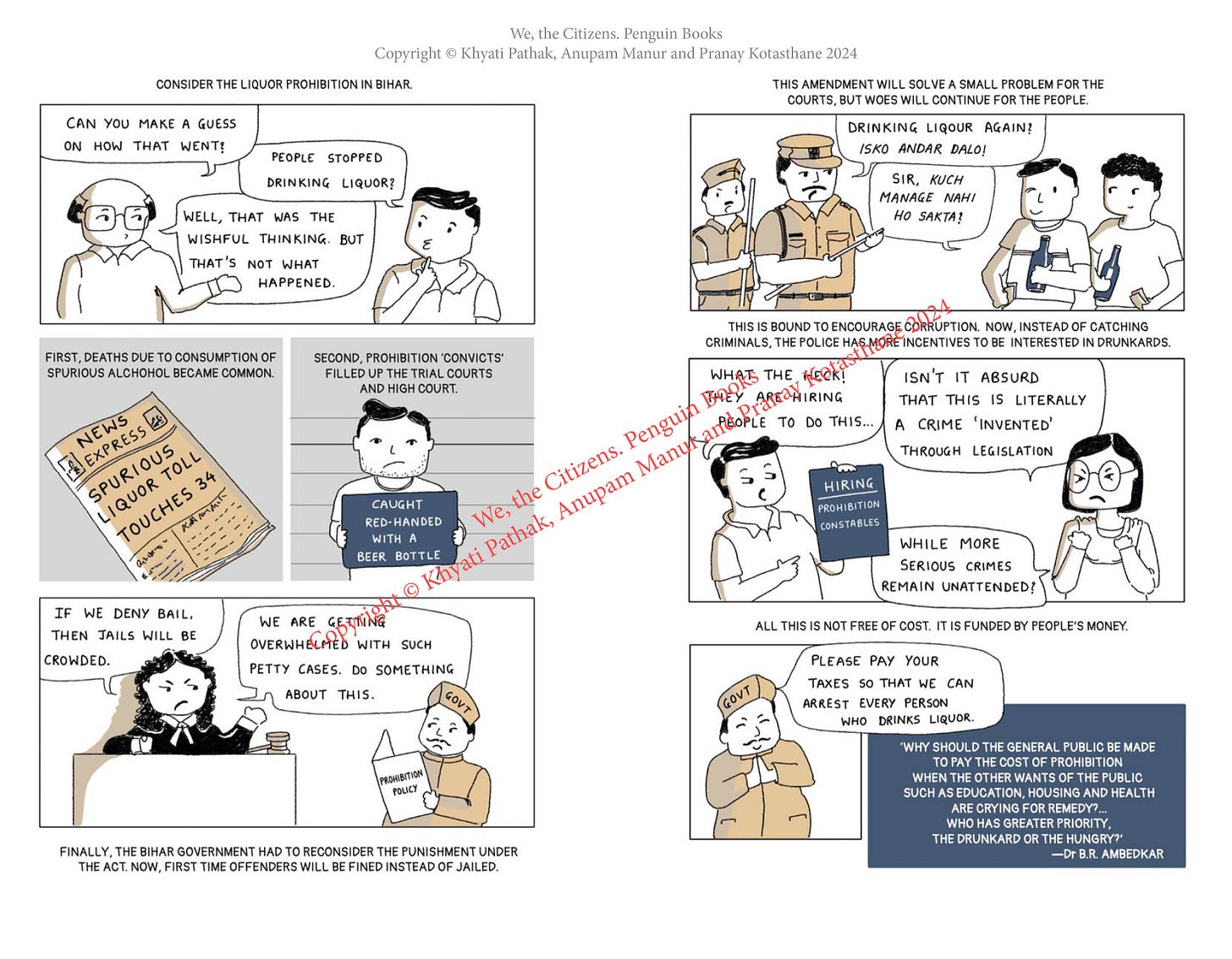

We announced our book last year on Republic Day. This Republic Day is no different. Drumroll. Announcing We, The Citizens: Strengthening the Indian Republic, published by Penguin India. Written by Khyati Pathak, Anupam Manur, and me.

Barun Mitra rues that the ‘public’ is often missing in public policy discourse. So, to bring the public back to the centre of Public Policy, we at Takshashila keep experimenting with various forms, and our latest addition is a comic book!

Yes, you heard that right. The brilliant Khyati Pathak has transformed policy ideas into an easily accessible graphic narrative. The book is perfect for anyone and everyone above 14 years of age. And it makes for a great gift.

Aap convince ho gaye, yaa main aur bolu? (God bless Jab We Met). Here’s the official blurb:

… the powerful play goes on, and you may contribute a verse.

-- Walt Whitman

What is a republic? How do markets work? What is the role of society in bringing about change? These may be abstract questions, but they have a concrete impact on all of us.

We, the citizens, live at the intersection of the Indian state, market and society. Yet, many of us are unaware of what these entities stand for, how they interact with each other, and how they touch our lives.

We, The Citizens, by Khyati Pathak, Anupam Manur and Pranay Kotasthane, decodes public policy in the Indian context in a graphical narrative format relatable to readers of all ages. If you want to be an engaged citizen, aspire to be a positive change-maker, or wish to understand our sociopolitical environment, this book is for you.

The idea of India was an audacious dream. The fulfilment of this dream lies upon We, the citizens.

And here’s what economist Ajay Shah has to say about the book:

“Everyone who is interested in India should read this. Everyone who is interested in India should buy this for their WhatsApp uncle".

So, what are you waiting for? We hope you will enjoy reading it and recommending it to others.

Global Policy Watch #1: Tractor Troubles in Europe

Global policy issues relevant to India

— Pranay Kotasthane

The recent spate of farmer protests in Europe caught my attention. Over the past few weeks, farmers have protested in Germany, Poland, Romania, Austria, and the Netherlands, blocking roads in many cities with their tractors (rings a bell?). So, how should we, in India, understand these protests? Are there similarities between the agriculture-state relationship in Europe and India? Here are a few pointers.

Let’s begin by dividing the reasons for farmer unrest in Europe into two categories: the proximate and the structural.

Proximate Reasons

Two proximate reasons exist: the ongoing war in Ukraine and climate change mitigation policies.

No domestic producer likes competition from foreign players. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU temporarily lifted restrictions on Ukrainian agricultural exports. Ukraine is a heavy hitter in agriculture — it has a large area under cultivation and, hence, large farm outputs compared to the smaller farms in many European states. Thus, the sudden entry of Ukrainian farm output has angered European farmers. Farmers are also apprehensive about the ongoing trade negotiations with the South American MERCOSUR block, which will result in cheaper imports coming to the EU.

Climate change policies have also played their role. The European Green Deal—a set of policies that aim to make the EU climate-neutral by 2050—is facing the wrath of farmers. This deal seeks to commit the EU member-states to climate transition by setting targets for reducing pesticide use, developing organic farming, protecting biodiversity, and sunsetting fossil fuel subsidies in agriculture. This vision has resulted in specific national policies, which farmers are opposing. For instance, the proximate cause for protests in Germany was the government’s policy to phase out diesel subsidies in agriculture. In France, the anticipated ban on certain pesticides is animating farmers.

Structural Reasons

Underlying these proximate causes is a set of structural reasons that makes protests by farmers more likely than by consumers or small-business owners.

Farmers account for just 2% of total employment in France and 1% in Germany. They correspondingly account for 1.6% of France’s GDP and 0.7% of Germany’s economic output (see the comparative charts below). Despite their minuscule numerical and economic presence, unlike in India, farmers wield disproportionate political leverage. But why?

The first reason is the entitlement effect. In the EU, farming is heavily subsidised through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). This policy to subsidise agriculture goes as far back as 1962 when farming was a bigger chunk of the EU’s GDP, the wounds of the World War shortages were still raw, and farming itself was a risky economic activity due to the extreme dependence on nature’s vagaries. Under the CAP, national agricultural support policies were kicked up to the European Economic Community (EEC) to achieve the goal of a Common Market. This CAP, at one point, constituted over 70% of EEC’s expenditure. Today, it has halved to about 35% of the EU’s budget (2020) and comes majorly as income support given to farmers and households. Any move to reduce these subsidies or to align them with climate transition goals causes backlash. There’s also a political economy angle here. Since the EU makes the CAP and not the member states, underperforming national governments can always blame the ‘complex bureaucracy’ of the EU for their failures.

Then there’s also the ‘Jai Jawaan, Jai Kisaan’ romanticism. The falling fortunes of agriculture in the EU were a primary justification for protectionist policies. Consumers bit the bullet then and have been paying for it ever since. People like the idea of farming and see it not just as an ordinary economic activity but as a way of life that needs to be preserved.

The third reason is interest group management. In a paper titled Why is the Agricultural Lobby in the European Member States so Effective?, authors Bednarik and Jilkova see Mancur Olson’s Logic of Collective Action at work:

“… consumers and taxpayers are very submissive in an acceptance of CAP measures relating to agricultural subsidies. The farmer’s interest to gain support is much higher than the interest of consumers and taxpayers to eliminate them. The interests of farmers are defended by tens of different European groups, which together conquer the lobbying capacity of potential countervailing interest groups such as consumers or environmentalists. Agricultural associations also receive their organisational success both due to its ability to respond to a wide range of needs and services supplied by farmers in the form of selected stimuli. In addition, MacLaren [17] identifies another four factors that, to a great extent, could explain the strong influence of the agricultural lobby: the solidarity of the agricultural organisations; the inter-institutional relationship between agricultural organisations and the ministry of agriculture, the importance government attaches to agriculture and the status of the ministry of agriculture in national government.”

Finally, farmers, whether in India or in Europe, have greater protest capacities. Tractors and other heavy farm machinery are tools that have been repurposed for road-blocking protests on many occasions. Also, the temporal cycles of agriculture, with lean seasons in between, mean that farmers can get away from work to participate in long protests lasting days or weeks. The opportunity cost for them in the off-season is far less than it would be for a small-business owner or an industrial worker.

So, What Are the Takeaways?

As Europe’s story illustrates, the farmer protests we witnessed in India in 2020 aren’t an exception. While the proximate factors may differ, the structural factors underlying the protests are somewhat similar.

Seeing European agriculture in a pickle—or should I say—a polycrisis, some Indian commentators have argued that the EU should adopt policies that guarantee prices to farmers for their produce, much like the Minimum Support Price (MSP) in India, because freer markets haven’t provided any succour to them.

But that would be a wrong reading of the situation. If anything, as I explained, there is excessive government involvement in agriculture. Much more so in India, where the State also imposes export bans at will, makes land consolidation near impossible, bans futures trading in agricultural commodities, and prohibits easier adoption of GM crops. Europe will make its way out of this polycrisis through some compromises because the numerical strength of farmers is quite small. India won’t unless we give markets a fair chance in agriculture. Ultimately, we need to analyse agriculture as any other economic activity minus the glorification and romanticism associated with it.

Global Policy Watch #2: The Inflation Prediction Challenge

Global policy issues relevant to India

— RSJ

Inflation is getting harder to predict. If you went back to the inflation predictions made by various economists, central banks and analysts at the beginning of 2023, you will find they were off by anywhere between 30-50 per cent. This isn’t restricted to a particular region alone. Almost every major economy got its inflation prediction wrong by a margin. Now, this is a problem. Central banks like to keep prices stable and range-bound. So, they must act in advance, and their only instrument is the nominal interest rate, which they use to correct price distortions in the economy. Or, they take indirect steps to influence interest rates by actively managing liquidity in the economy. If you get inflation forecasts wrong on the higher side, that is, the actual inflation comes lower than your predictions as it did in 2023, you will end up either keeping the interest rate higher than necessary or you would have kept liquidity tight in the system. Both of these measures will impact growth in short and medium term. But then inflation prediction is a difficult business. What can one do to improve it?

Is 2024 going to be any different on the prediction front? Not from the looks of it. For instance, in the October MPC meeting, the RBI made this statement on keeping liquidity tight:

“A risk to the inflation outlook stems from the liquidity overhang in the banking system” wrote RBI DG and MPC member Michael Patra, in his minutes to the August policy. Patra went on to say, "Withdrawal of excess liquidity should engage primacy in the attention of the RBI going forward as it presents a direct threat to the RBI/MPC resolve to align India’s inflation with the target, besides the potential risks to financial stability.”

Well, that tight liquidity focus because of inflation fears meant that system liquidity slipped into deficit in late 2023. If you read the commentary from banks during the current results season, this squeeze on liquidity means they are unable to lend despite the demand environment being good. In fact, most banks have flagged a slowdown in credit offtake next year because of how difficult it is to raise deposits in this tight environment. We are actually going to take a hit on growth because we don’t trust the predicted inflation to come in lower. Things are no different in the U.S. If you consider all the variables that go into the Taylor rule, the interest rate should be around 4.5 percent, which is almost a percent lower than the actual rate right now. The market is already budgeting for four rate cuts or more during the year. But that textbook view is totally at odds with how the Fed or the businesses ‘feel’ about inflation in the year ahead.

A key problem in inflation forecasting seems to be the extent of supply-side disruptions that have become a feature of the global economy in the past five years. The stickiness of price across multiple products and services is getting impacted by production shocks more often than in the past. And the current models of inflation prediction used by central banks don’t index for supply-side disruptions. This is a problem because just the last five years have shown how vulnerable global supply chains are to random global events. We have had a global pandemic, two ongoing wars, a disruption of the shipping traffic at the Suez, and political shifts that suggest more protectionism in developed economies – all of which are negative supply shocks for critical commodities. More so when these constraints are applied on already tight networks like shipping, where the global container count is limited, and ports have limited capacity to store or dock ships. A choking of a global lifeline like the Suez by rogue elements like the Houthis for a month and you could have shortage and price distortion on multiple commodities around the world. Those shortages will push up inflation. And any attempt to maximise output to address this will lead to demand-driven inflation a few quarters down the line. This is exactly what happened during and after the pandemic in the U.S.

Now, that we have had a couple of years of data post pandemic, I was looking for academic work that might have been done to understand the post pandemic inflation phenomenon and a better understanding of how supply side disruptions impacted inflation. That led me to this paper by Elisa Rubbo of Harvard University, which has been updated for post-pandemic data. Rubbo points out that the baseline New Keynesian model has a problem – it assumes only one sector of production, while a real economy has multiple sectors which trade in intermediates.

As she writes:

"There are crucial issues that the model is silent about. What is the correct definition of aggregate inflation, based on the production structure? How should central banks trade-off inflation in different sectors, depending on their position in the input-output network?

I extend the New Keynesian framework to account for multiple sectors, arranged in an input-output network. Sectors have arbitrary neoclassical production functions, and face idiosyncratic productivity shocks and heterogeneous pricing frictions. I solve the model analytically, providing an exact counterpart of traditional results in the multi-sector framework."

In the one-sector model, as taken by the conventional framework, the central bank can fully withstand productivity shocks by targeting zero inflation. This is what is called the “divine coincidence” theory, as postulated by Olivier Blanchard and Jordi Gali in their seminal article “Real wage rigidities and the New Keynesian model”. What it means is this. If there is a positive demand shock in the economy like increased government spending (as it happened during pandemic in the U.S.), both output and inflation rise. Since output and inflation move in the same direction, it is assumed that efforts to bring inflation down will also stabilise output. This is the divine coincidence where stabilising inflation stabilises output gap too and there is no trade-off between these objectives. This coincidence is attributed to a feature of the model: the absence of real imperfections such as real wage rigidities. Therefore, if the model were to consider these real imperfections, the divine coincidence would disappear, and central banks would again face a trade-off between inflation and output gap stabilisation.

This is where Rubbo’s work comes in handy. To quote her:

“I derive the two key objects which constitute the “backbone” of the optimal policy problem: the Phillips curve and the welfare loss function. Building on this result, I construct two novel indicators. The first inherits the positive properties of inflation in the one-sector model, and therefore can be viewed as its natural extension to a multi-sector economy. Specifically, this index yields a well-specified Phillips curve and it is stabilized together with aggregate output (a property which is referred to as the “divine coincidence”). The second indicator instead serves as an optimal policy target. These two indicators are distinct, and they are both different from consumer price inflation.”

In simple words, while she suggests that in almost every case, it is best for the central bank to focus on demand-side disruptions to stabilise prices, her “divine coincidence index” can help central bankers break up the inflation into components and understand what parts can be attributed to supply. The presence of multiple sectors presents the central bank with a tradeoff between stabilising aggregate output and implementing the correct relative output across firms and sectors. That would then make them a bit more tolerant to inflation in general. Her point is to target specific parts of the demand side of inflation using the tool you’ve got and ignore supply-side issues, which will take care of themselves. Looking at the inflation number without disaggregating it leads to a bigger intervention in raising output, which makes inflation worse afterwards.

Global Policy Watch #3: Oh, The Populists Are Rising Again

Global policy issues relevant to India

— RSJ

With Trump marching onto an inevitable Republican ticket and possibly into the White House and scores of other populists across, Germany, France, Sweden and elsewhere in the world leading national opinion polls, we are back to columns talking about democratic backsliding, liberal retreat and the assorted impact on global economy because of populist policies that will inevitably follow their wins. We have been here before during Trump’s presidency when similar concerns were voiced. So, the question is how justified these fears are based on previous experience.

Well, Janan Ganesh in this FT piece thinks these are somewhat unfounded. The track record of the economy under the so-called populists in democracies hasn’t been bad barring say an odd Erdogan. This is a problem for the liberals, he writes.

“This is the liberal nightmare: not that populists abolish democracy to remain in power, but that they perform well enough not to have to.

It is also intellectually confounding. Populism should be bad economics. It tends to set itself against things conducive to growth, such as immigrants (who expand the labour force), judges (who enforce contracts), technocrats (who set interest rates and competition rules) and free trade. Business professes to hate arbitrariness, the defining feature of strongman rule. Better a bad but consistent law than a leader’s personal caprice. The autocratic habit of feuding with independent central bank governors should on its own depress the animal spirits of investors.

Yet here we are. Of the world’s most famous populist heads of government, how many have a defining economic failure on their record? Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, perhaps. Other than his losing fight with inflation, there are fewer examples than you’d think. Italian growth is not much slower under Giorgia Meloni than it was under more conventional prime ministers. Benjamin Netanyahu has been feted abroad for Israel’s economic performance.”

What explains this?

Ganesh offers two reasons:

One view is that, from the beginning, we commentators lost all sense of proportion. These “strongmen”, “autocrats” and “demagogues” are much more pragmatic than such excitable language allows.

A bleaker view is that economic harm takes time to show. This month, Lawrence Summers warned US corporate bosses against embracing Trump. Citing Mussolini, the economist said such wild leadership can be of transient use to business but “ultimately brings a great deal crashing down”. The important word is “ultimately”.

The problem is what to do in the meantime. How to explain the data away based on theory?

As Ganesh writes:

“Think of the ideological challenge here. It was awkward enough that China enriched itself without democratising. If existing democracies become authoritarian without getting poorer, even the sunniest liberal will feel night closing in.”

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] A Puliyabaazi on the history of constitutionalism.

[AtU #103] The Constitution Chronicles - Four Books and Two Speeches.

Pranay, since you hold the opinion less governmental interference in agriculture is better for the long term growth of agriculture in India, would you also say the farm bills was step forward towards that embracing a free market approach in agriculture?