#267 Bayesian Updating

Why Equity Markets Fell, Why Indian Firms Don't Innovate Enough, and How to Structure an Economic Policy Approach Towards China

Global Policy Watch: Swingin’ Times

Global policy issues relevant to India

— RSJ

One of the truths I hold dear about global macros is that no one knows anything. Everybody becomes wiser after an event and provides an explainer on what just happened. But no one could see it coming. For instance, about as late as a month back, most analysts had a broad consensus about the global economy, which went like this - the US economy would have a soft landing, there might be a couple of rate cuts amounting to 50 bps by the Fed by the end of the year, employment data would remain robust with 150K - 175K jobs created on a monthly basis, inflation would remain stable, and there was no fear plaguing the markets. And then we had a wild last week where the equity markets fell between 5-6 per cent on Monday and by Friday had recovered most of it; the markets now pricing in a 125 bps rate cut before the end of the year; the Vix (volatility index) or the ‘fear gauge’ up by 40 bps and most people worried about a recession and ‘hard landing’ for the US economy. And that’s just in a week. If I were to stretch the horizon back to the start of 2024 and see how the consensus view on various macro indicators has yo-yoed, it would make you a tad dizzy.

Like I said, no one knows anything.

But why should that stop me from attempting to explain what happened last week and what that portends for the future?

To begin with, we will start with Japan. On July 31, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) raised short-term interest rates to 0.25 per cent from 0-0.1 per cent, a level last seen back in 2007. That’s a total of 35 bps increase in about four months. It also announced it will slow down its monthly bond-buying program by half. This was not what the market expected, especially after the BoJ had ended a decade-long tenure of negative interest rates only a few months back. Clearly, the BoJ Governor, Kazuo Ueda, who assumed office in March 2023, is in the mood to dismantle the quantitative easing regime, which was done to reflate the economy that Japan has gotten used to for so long. The idea is to tighten and reduce the stimulus by halving the bond purchase, increase the rates gradually, lighten the balance sheet over time and ‘normalise’ the monetary policy over time. With inflation at two per cent and decent growth numbers forecast by Japanese benchmarks, the time is right to begin a taper, or so the BoJ thinks. But this set in motion the next act in the play.

This surprising decision of BoJ to be hawkish contrasted with the market expectations of a couple of Fed rate cuts before the end of the year. Now for years global investors have been taking advantage of the zero interest rate regime in Japan to borrow short in yen to buy all kinds of better-yielding assets around the world. This has been going on for years, and you see this in India as well, when you notice Japanese banks and conglomerates pay premium prices for stakes in Indian assets. This is what is called the ‘yen carry trade’. This is what has likely led to the insane run-up in the valuations of Nvidia and other tech stocks in the US. It is what fuels the large fundraises that VCs/PEs have been doing since the end of the pandemic, and it is present in everything else, from investors building large positions on the Mexican peso, betting on emerging market equities or supporting real estate funds. It works so long as interest rates in Japan stay low relative to the rates in the markets where you make the yen investments (largely the US). This has gone bonkers in the last couple of years after the Fed started raising rates and reducing the stimulus after the pandemic.

The arbitrage opportunity only kept going one way. Up. Cheap money for investors in the past decade of quantitative easing has been like water to fish. They swim in it but they seem to have forgotten it exists. Only when the liquidity starts draining away, does the truth hit home. With Japan tightening and raising rates and the US planning for rate cuts, the logic of the ‘yen carry trade’ inverts on its head. And that meant this past week investors started unwinding their positions. This is never easy because, eventually, someone has to stump up the money when positions are being unwound. And given no one is sure of the size of the yen carry trade, everyone panicked last week when it happened. So, there was a massive sell-off of tech stocks, the yen rose against the US dollar, and the yields on bonds went to a one-year low. Is this unwinding all done? The general view is about half of the $500 bn of outstanding cumulative carry trade has been unwound. But who knows? There’s this J.P. Morgan note that’s floating around on yen carry trade which might give you a sense of the possible size of the total yen carry trade in all its avatars. I have extracted a few points below:

“In our opinion, there are three main components of the yen carry trade.

One component of the yen carry trade directly related to equities is the purchases of Japanese equities by foreign investors on a currency-hedged basis. Currency hedging implies a short yen leg which is combined (as a package) with the Japanese equity leg. As the short yen leg backfired recently, investors were forced to unwind the whole package, i.e. to unwind the Japanese equity leg also. Assuming that much of the cumulative increase in Japanese equity holdings of foreign investors since end-2022 has been currency hedged given the seemingly relentless yen weakness, before the past week’s correction the cumulative size of this yen carry trade was around $60bn (cumulatively since the BoJ trade emerged at the end of 2022).

Second, there is an implicit yen carry trade when foreign investors borrow in yen to fund purchases of foreign assets including equities and bonds. Borrowing in yen by foreign non-bank investors was worth around $420bn at the end of Q1 2014, according to BIS. Unfortunately, it is difficult to gauge this second component of the yen carry trade on a high frequency basis as the data are quarterly.

Thirdly, there is a domestic (and the biggest) component to the yen carry trade which involves Japanese investors buying of foreign equities and bonds. For example, Japanese pension funds buying foreign equities or bonds do so to meet their yen-denominated future liabilities making it an implicit carry trade.

Adding all the above three components together, the total size of the yen carry trade is estimated at around $4tr.”

That’s a lot of volatility potentially waiting to be unleashed.

Immediately on the back of this announcement by the BoJ came two data points that spooked the market about the health of the US economy. Data showed that the US manufacturing activity hit an 8-month low, with new orders for US manufactured goods falling by 3.3 per cent. This was followed by data on the jobs market that showed the US economy added only about 115,000 new jobs in July against the expected figure of 180,000. This data, coupled with tepid results from Amazon and Alphabet and some talking down of AI hype by the players, led to a rout of tech stocks. The worry about growth became real, and the spectre of recession raised its head with the “Sahm Recession Rule” coming into play. Sahm rule is an empirical observation about the relationship between unemployment and an impending recession that has held since the 1970s, and it predicts that the initial phase of a recession has started when the three-month moving average of the U.S. unemployment rate is at least half a percentage point higher than the 12-month low. The rule was triggered with the job data from July and pointed towards a building momentum towards recession. That added to the worries of investors that the Fed has been late on cutting rates and boosting growth and further built the case for more rate cuts for the year. The Vix ‘fear gauge’ went as high as 65 as geopolitical risks continued to remain high with the volatile situation in West Asia and the US presidential elections going from a predicted Trump win to a toss-up. No surprise then that the emerging markets caught a cold on Tuesday.

Like I said before, much of this was recovered by the end of the week capping off a crazy week, but the broader points remain. We are at the end of the pandemic-driven surplus liquidity regime. There will be a taper, and it will hurt. Tech stocks and AI hype have entered the bubble territory, and with the unwinding of the yen carry trade remaining, there will be some more correction inevitable in the markets. The top 7 tech stocks account for almost a third of the total US market cap, so a wider pain is inevitable when tech stocks correct. It is not volatility that’s confounding people these days as much as the rate of change of volatility. This second order differential of volatility or “vol of vol” is on account of multiple things. There’s the deeply complex and interconnected nature of global financial markets that makes it difficult to discern between cause and effect. It is all circular and convoluted. Also, there’s so much more data being generated, parsed and overanalysed, leading to all kinds of often contradictory views emerging within a short span. One of the things we have to learn in an age of excess data flow is which data to act on and which data to merely observe. Unfortunately, people are paid to act, and the more data they see, the more the temptation to act. This action gets further compounded when you realise how much of it is auto-triggered in these days of algorithmic trading. The whipsaw of volatility just keeps ratcheting on. Lastly, as the Fed begins to cut rates inevitably from September onwards, it will be interesting to see how India responds. The MPC meeting that concluded on Wednesday kept the policy stance unchanged while talking up the risks of food inflation. The headline inflation isn’t representing the price rise on food that’s affecting the poor seems to be the underlying concern. It will be difficult to stand apart from everyone else for too long when the Fed rate cuts start next month. We aren’t so decoupled from the rest of the world. The quandary will then be of a less than comfortable food inflation on the one hand and the need to cut rates to be in step with the Fed. The political economy, of course, cannot afford high food inflation, given a few state elections around the corner.

Come winter, things will get interesting.

India Policy Watch: Why Does India Underperform in Firm-level Innovation?

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

Sarthak Pradhan and I have a policy paper for The 1991 Project that attempts to answer this crucial question. We have often discussed in these pages that corporate R&D is the real culprit in India’s underperformance on innovation metrics; government R&D is, in fact, in line with India’s income levels.

Thus, to increase India’s technological power, we must understand the policy impediments that have blocked Indian firms from undertaking technology upgradation. The solution usually proposed for this problem is one policy change — increase R&D tax credits, ramp up local sourcing, or revamp the intellectual property protection regime. But we know that the problem runs much deeper. So, we eschewed a one-dimensional analysis and instead deployed the tools of complexity to locate all interrelationships that impinge on firm-level innovation. As we write in our conclusion:

One way to address the problem of India’s lack of innovation is to focus on a specific industry domain and identify narrow policy “recipes.” Instead of this approach, in this paper, we identified systemic linkages using complexity theory to pinpoint the policy “ingredients” that have hindered technological upgrades and innovation. Based on this analysis, we have identified solutions that, if implemented, could help India transition to a more innovative and advanced industrial landscape.

Here’s what our analysis led us to.

“Based on the complexity analysis and the case study, we arrive at three leverage points: corporations, universities, and R&D systems. Prioritizing these domains would lead to significant gains in innovation.

Regarding corporations, the government must prioritize creating an enabling policy environment that attracts both foreign and domestic investments and facilitates their scaling up. Effective policy mechanisms in this regard could include reducing tax rates and enhancing tax certainty by improving the country’s capacity for concluding APAs and BITs. The policy environment must remove impediments that prompt startups to relocate outside India, such as arbitrary treatment. Additionally, the government should remove restrictive labor legislation that is out of step with the current realities.

Regarding universities, India’s innovation system needs to tap into the intellectual capital of top talent outside India. However, given India’s current developmental stage, enticing these researchers may prove challenging. The decision to relocate is influenced by multiple factors, including quality of life and opportunities available for spouses. Special fellowships or monetary incentives, similar to those employed by China, might not be sufficient to persuade individuals to move to India permanently. Additionally, such incentives can lead to contentious situations, including allegations of intellectual property theft and espionage from the host countries. Given these constraints, the most viable approach would be facilitating collaboration between Indian researchers abroad and those in India. It could be achieved through joint research programs and by establishing hubs of excellence in geopolitically favorable and livable locations such as Dubai, Singapore, or Melbourne.

The current higher education regulatory environment diminishes the ability of private players to respond to market needs, resulting in decreased investments and competition in the sector, which limits innovation potential. Simplifying the regulatory approval process and enabling higher participation of foreign universities in the economy can help alleviate these challenges.

Given the pivotal roles that universities and corporations hold in an economy’s R&D ecosystem, the policy recommendations outlined above will also help improve the R&D ecosystem. In addition to these measures, the government could explore enhancing R&D tax incentives to scale innovation. Technology transfers from geopolitically favorable partners such as the Quad countries could also propel India’s R&D system to the next level.”

I feel this is a grand intellectual puzzle that should be a focus area for the Indian government over the next decade. We have barely scratched the surface, but using a systems analysis approach, we have identified some underlying and interconnected reasons for Indian firms’ under-par performance.

The full paper is here.

India Policy Watch #2: A Framework for India’s Approach Towards Chinese Firms

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

Quite a few articles over the past week have highlighted that Chinese firms will resort to aggressive exports to resolve the burgeoning overcapacity problems. First, The Economist points out that nearly 30 per cent of industrial firms were loss-making at the end of June 2024, beating the troubles of the Asian financial crisis in 1998. Moreover, the number of loss-making companies has surged by 44 per cent this year already.

On the same theme, Zongyuan Zoe Liu has an excellent Foreign Affairs piece, which does a general equilibrium analysis of China’s industrial overproduction. It lays the blame on a planned approach that structurally privileged industrial production for decades over household consumption:

“As the party sees it, consumption is an individualistic distraction that threatens to divert resources away from China’s core economic strength: its industrial base. According to party orthodoxy, China’s economic advantage derives from its low consumption and high savings rates, which generate capital that the state-controlled banking system can funnel into industrial enterprises. This system also reinforces political stability by embedding the party hierarchy into every economic sector. Because China’s bloated industrial base is dependent on cheap financing to survive—financing that the Chinese leadership can restrict at any time—the business elite is tightly bound, and even subservient, to the interests of the party. In the West, money influences politics, but in China it is the opposite: politics influences money. The Chinese economy clearly needs to strike a new balance between investment and consumption, but Beijing is unlikely to make this shift because it depends on the political control it gets from production-intensive economic policy.” [Zongyuan Zoe Liu, Foreign Affairs]

This strategy creates a negative externality for firms in other countries:

“In prioritizing industrial output, China’s economic planners assume that Chinese producers will always be able to offload excess supply in the global market and reap cash from foreign sales. In practice, however, they have created vast overinvestment in production across sectors in which the domestic market is already saturated and foreign governments are wary of Chinese supply chain dominance. In the early years of the twenty-first century, it was Chinese steel, with the country’s surplus capacity eventually exceeding the entire steel output of Germany, Japan, and the United States combined. More recently, China has ended up with similar excesses in coal, aluminum, glass, cement, robotic equipment, electric-vehicle batteries, and other materials. Chinese factories are now able to produce every year twice as many solar panels as the world can put to use.” [Zongyuan Zoe Liu, Foreign Affairs]

Finally, the Urbanomics blog tackles this question from India’s perspective. It argues that Chinese firms will not make any significant investments abroad as they don’t have an excess capital problem but an excess capacity problem, which can only be solved by ramping up exports.

Our prognosis is not so negative. As Chinese firms’ profits get squeezed at home and doors close on their low-price wares in the developed world, developing countries have the opportunity to attract and learn from Chinese firms.

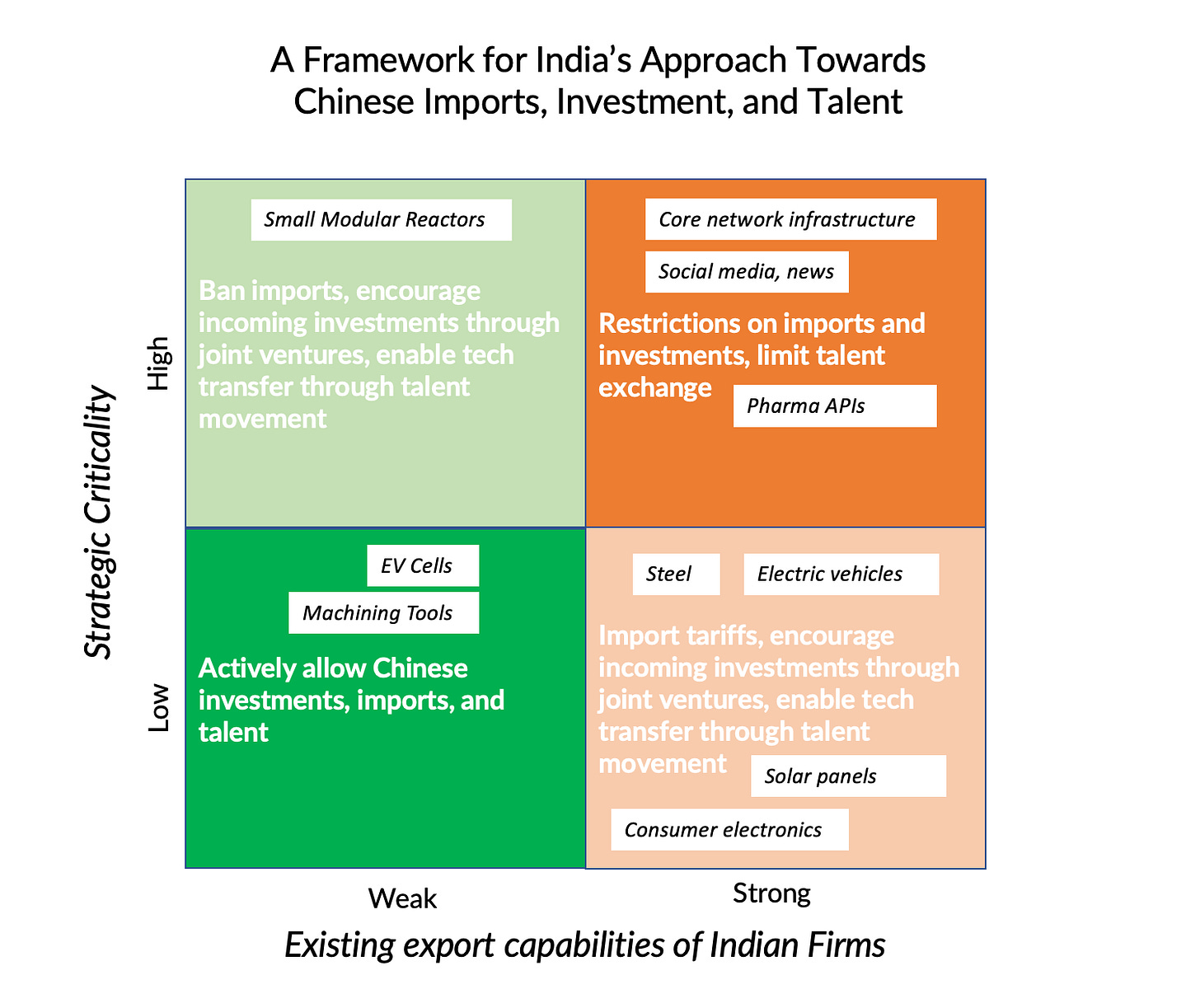

So, what could a calibrated approach to an economic partnership with Chinese firms look like? Although we did give a thumbs-up to the Economic Survey’s argument in favour of Chinese investments (edition #265), we didn’t discuss the factors that can help determine the policy attitude towards Chinese firms. Here’s an attempt.

Perhaps the two most important factors that should determine India’s attitude towards Chinese firms are:

Strategic criticality of a product or a sector, i.e., is the product crucial to India’s national security, defence, or information space? Are Chinese firms the only suppliers of the product or the only players in the sector?

the existing capacity of Indian firms. Since Chinese firms’ overcapacity fueled by government subsidies and its governance model can decimate global competition, supporting competitive Indian firms becomes necessary. To measure existing capacity, a demonstration of export potential is a good indicator as firms in India are protected through various means, thus domestic performance can overestimate competitiveness.

The intersection of these two factors produces four scenarios, as shown below.

The responses in each of the scenarios have three prongs: investments, talent, and imports. In areas with low capability and criticality, Chinese investments, imports, and talent (to enable technology transfers) should be welcome. Conversely, in the critical areas where Indian firms have demonstrated export competitiveness, existing restrictions on imports, investments, and talent should continue.

Specific areas identified in each of the quadrants need further scrutiny. For example, I am not sure how strategically critical machining tools are. Nevertheless, the approach should hold regardless of the examples. What do you think?

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Paper] Jeff Ding has a fantastic paper which argues that general-purpose-technology diffusion—not leading sector innovation—determines national power.

[Podcast] The Olympics 2024 ends today. The latest Puliyabaazi is a deep dive into the philosophy that guides sporting competitions and the interests that determine sports governance. Do not miss it.

Two short, online, cohort-based courses are on offer at OpenTakshashila that will interest you—one on Life Science Policy and one on Sports Governance. These are cutting-edge topics in public policy, so do check them out and get equipped.

Re policy on rnd: coming from a tech perspective -- the biggest hindrance is lack of education quality and incentive to pursue higher education in India. I am a PhD student in the US, as are tonnes of others. The quality of graduate education -- in everything, rigor, funding, quality of peer group, quality of life, and post graduation opportunities is not comparable at all. As someone who did an undegrad at one of the top institutions -- there is barely good research happening in Indian academia (there are pockets of exception of course but they are small). The salaries are meagre!! And the misogyny and politics in academic department is horrible. I am not saying that this does not exist in the US. But the planes of levels are completely different. There were not many places (maybe 2) I would have considered doing a PhD here -- and that no way compare to the offers I had in the US. And truth be told, I don't feel lured to come back to India as a professor if things don't drastically change in the next couple years (which is unlikely). Unless we are able to change that -- RnD will remain dependant on foreign investments and tie ups with foreign researchers, both of which are at best short term solutions.

Thanks, Pranay - will check out the index