#299 General Equilibria

India-Pakistan Strikes and Counter-strikes; and What a Failed Chip Fab Plan Means for India

India Policy Watch: SitRep#1 May 10 1600 IST

Insights on current policy issues in India

—RSJ

This was written before Trump stumped all of us with his post on Truth Social about a ceasefire agreement between India and Pakistan. The nature of US mediation isn’t clear at this moment. It is possible they only facilitated what both sides already wanted. In any case, the core points written about the escalation this week still hold.

Last week, we wrote about the retaliation conundrum that India faces following the Pahalgam attack. The retaliation had to be meaningful in hurting terror groups based deep within Pakistan, it had to address the domestic anger about the loss of innocent lives, and it had to be not too escalatory considering the nuclear deterrence available with both sides. On Wednesday, India launched Operation Sindoor targeting Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir and destroying the terrorist infrastructure across 11 different sites. This, to India, seemed like a proportionate response aimed at non-civilian targets that fulfilled the conditions laid out for retaliation. Pakistan claimed these were civilian locations and blamed India for the death of over 30 people. Considering that, unlike Balakot, where the strikes were focused on a single location and weren’t preceded by statements about a definite response, it was to be expected that these strikes at multiple locations deep within Pakistani territory would elicit a different response. The question was how different.

On Thursday evening, Pakistan responded with between 300 and 400 drone strikes across 36 different Indian sites. These drones flying over Indian cities were engaged with and neutralised by Indian forces with no loss of lives. Now, one could argue this was an escalation over what India had done the previous evening. Pakistan, of course, claimed these were proportionate and justified responses. The key to any de-escalation in a war-like scenario is the ability of both parties to claim to have the last word for their domestic constituency. This is difficult because there will always be a desire for a tit for tat response. The confidence not to chase after the last word comes from a hard-headed appreciation of potential gains and losses of a continuing war. On Friday, I thought we had reached that point already in this skirmish where both sides could claim to have had the last word. The optimal strategy for India then was to keep the rhetoric low, confirm minimal loss to India and not indicate that it got better off these exchanges. The press briefing on Friday morning by the Indian defence establishment went exactly along these lines. It suggested we have seen you off; we are done now. This made sense. Pakistan is an international basket case that’s alive on IMF aid and Chinese doles. India is a fast-growing economy that doesn’t want to be tied down by its neighbourhood. India had more to lose with continued escalation.

However, on Friday evening, there was another series of drone attacks from Pakistan with renewed intensity over civilian areas. India responded with a few missile strikes at key air force bases within Pakistan. This was then followed by a sustained series of missile attacks by Pakistan on various Indian cities. So far, this has been thwarted effectively. There was also significant shelling along the LOC on Friday night. If the path to de-escalation was laid out by India on Thursday, this was a clear signal that Pakistan isn’t interested in it. This was a surprise, and one has to ask what the Pakistani calculus is here.

The obvious reflexive Indian instinct is to believe that in Pakistan, we are not dealing with a rational actor. The Pakistani army would like nothing better than a prolonged face-off with India to give a boost to its credibility among its citizens and to undermine the elected government in power. This would also mean strengthening the military complex with higher budgets and more arbitrary power being handed over to the army. Some of this is at play as I write this, and the situation appears to be slowly spiralling into something more than just a skirmish. But it might make sense to go beyond this obvious line of thinking. Pakistan is possibly making three key assumptions right now about the future. First, it is positioning itself as an underdog, a David, in this fight with the Goliath. This is clear in its social media strategy right now. The idea is to gain internal sympathy and support from the likes of OIC members and China. This gives it international aid, weapons and funds to keep India engaged and also to tide it over a domestic economic crisis. An early win in this strategy was the IMF loan that came about yesterday, despite India’s misgivings on how Pakistan has abused these funds in the past. Second, Pakistan is already seeing early success with this low-grade drone warfare. The losses with drones don’t matter much, while any minor success is a lottery. It can keep a steady source of drones from its friends and allies from the international market and exhaust India over a long period of time by keeping a large part of its border cities and states in a state of war. The Ukraine war has shown how effective this strategy is that can erode any air power superiority one day at a time. This is as good as its old ‘death by a thousand cuts’ formulation if the drone supply chain isn’t disrupted by India. Finally, Pakistan is betting on India wanting de-escalation more because of what it has to lose. Pakistan can continue to hold the world to ransom by holding a gun to its own head. This is its core competence. India, on the other hand, doesn’t want to be seen by global investors and partners as a site of an ongoing low-grade war that can potentially turn nuclear. Pakistan has no such qualms.

If these assumptions hold true, then Pakistan or its army will like to drag this war-like scenario for as long as possible.

Given that, what options does India have? The first is to continue to keep its response calibrated with a few key strikes inside Pakistan for all the drones sent across, and still look for de-escalation. There is a possibility that both sides can still claim some kind of upper hand following the events of Friday night and Saturday morning. India should use this for a potential de-escalation. Else, India might have many similar nights over the next few months, and each one of them will make a face-saving climb down by both parties difficult. It is in India’s interests more than Pakistan's to return to business as usual. That said, there’s every possibility that there could be more terror attacks in Kashmir by Pakistani-backed outfits in future. Will India keep responding at a higher level of intensity for every such incident? Because that’s the expectation that it has set now at home. If it does, the war-like scenario built up in the past week will become routine. Also, how high on a toughness scale can India continue to deliver a message every time another incident like Pahalgam happens? Maybe there are more rungs to this escalation ladder, but there can’t be infinite of them. Somewhere, India will hit the nuclear threshold. Then what? This is the ‘Pahalgam trap’ that India is in now, whether it likes it or not. Notwithstanding that, for now, India will have to work to find a mutually convenient opportunity that gives both sides some bragging rights and then stand down.

There’s a high-risk but low-probability option also given the above trap. India could decide to use this window to wage a 2-3 week war that will help it inflict heavy but not debilitating damage to Pakistani defence infrastructure while hoping it is not enough for a madman General to press the nuclear switch. If this succeeds, Pakistan gets a valuable lesson for supporting terror outfits, and India goes back to minding its own business. This is an option that plays with fire. But it can’t be ruled out now because I’m sure the Indian establishment will also have asked itself about what I have called the ‘Pahalgam trap’ above. In that case, expect things to worsen in the next month.

One of the questions that comes up during these discussions is what stance China is taking on this. For China, anything that keeps India bogged down is good news. So, it is in China’s interest to sell drones, armoury and weapons to Pakistan, which keeps India off global trade and influence. China is more interested in its contest against the US than in worrying about Pakistan. It will be happy to see India held down by the nature of its own circumstances. But China won’t want to be seen as openly supporting Pakistan when it is building itself as an alternative to the US as a responsible global power. So it will continue to export defence and manufacturing capacity to those who can afford it, but nothing beyond that. Separately, China’s economy isn’t doing great if you take a look at its Q1 FY25 data. Its fiscal situation continues to deteriorate with the total fiscal deficit at almost 10 per cent, revenues continuing to fall, and taxes coming almost 4 per cent lower y-o-y. All of this after multiple monetary stimuli and fiscal support to real estate in the past 12 months. Clearly, those bazookas haven’t worked so far. The tariff war with Trump won’t resolve itself anytime soon, so exports will struggle for the foreseeable future. China, therefore, has other things to worry about than adding Pakistan to its list of headaches. The most it might do is the old routine of mobilising troops on its Indian border to give India a thing or two to think about. But that will be that.

India Policy Watch: SitRep#2 May 10 2300 IST

Insights on current policy issues in India

—Pranay Kotasthane

The situation has evolved quite a bit since the last edition. In that edition, I had inferred from the PM’s statement on “giving operational freedom to the armed forces to decide on the mode, targets and timing of our response” that a kinetic response is likely but not imminent.

The kinetic response came four days later, earlier than I had expected. The May 7 strikes were significant for three reasons. First, India struck well-known terrorist targets in Pakistan’s heartland, not only in Pakistan-occupied-Jammu-and-Kashmir (PoJK). Second, it eschewed surprise in terms of the mode and timing of the attacks. Pakistan would have anticipated India’s use of airstrikes and the timing of the attack. One can only infer that India did so as a commitment device—that it is willing to respond in full view in response to a terrorist attack. And third, it was proportionate; it tried to contain escalation by using air strikes from inside India’s airspace, instead of using surface-to-surface missiles.

Pakistan had to seek an explanation for the failure of its air defences. So it first sought to project that the Indian strikes weren’t on terrorist camps but on civilian targets. Then it claimed it had shot down a few Indian aircraft. India’s official communication remained focused on the effect and nature of its strikes deep in the Pakistani territory. At this point, it felt like there was an opening for some de-escalation. Both sides could claim their victories and go home. But that’s not how it turned out.

Pakistan then attacked several locations in India using drones and missiles. Some of these attacks specifically targeted civilians. To justify these cowardly strikes, Pakistan maintained its ludicrous position that these attacks too were false flag operations by India, while its response was yet to come. This invited an Indian escalation. On 8th May, the Indian Armed Forces targeted Air Defence Radars at many places in Pakistan and took out an Air Defence system at Lahore.

By the 8th May, Pakistan’s narrative had weakened significantly. The photos of a US-designated terrorist leading the funeral function of terrorists’ coffins draped in Pakistani flags, with Pakistani military officials in the background, further reduced its credibility. Its claims about taking down Indian jets were not enough to explain its failure in defending against Indian attacks on key military sites. It chose to escalate further and responded with an even larger attack comprising drones, missiles, and aircraft. India then responded by hitting more military installations through drones and missiles.

By the 10th morning, it seemed that Pakistan’s position was weakening, even though its military took the position that it wouldn’t de-escalate. India had struck many more military targets in Pakistan with ease by then. Pakistan finally codenamed its retaliatory operation and increased its strike frequency across India. India formally acknowledged “limited damage was sustained to equipment and personnel at Indian Air Force stations at Udhampur, Pathankot, Adampur and Bhuj.”

The US Secretary of State spoke directly to General Asim Munir, in addition to talking to his counterpart on the Indian side. By the evening, Trump declared that both sides had agreed on a ceasefire. The Indian and Pakistani governments also confirmed this development. While the Pakistani PM quickly thanked Trump for securing the ceasefire, the Indian side tried to suggest that a bilateral understanding had been reached.

As I write this, there are continuing drone attacks on Srinagar and other areas, a mere three hours after the ceasefire was announced. However, firing on the Line of Control had stopped.

With the ceasefire announcement, the inevitable “who won, who lost” analyses have begun. Here’s my tentative assessment of the state of the play as of today.

One, India is better placed strategically. By hitting air bases all along Pakistan’s length, India has changed the payoffs for Pakistan. It has signalled that acts of terrorism against India will invite a response directly to Pakistani cities. By taking out air defence systems and runways in some air force stations, it has also exposed Pakistan’s vulnerability.

This assessment holds even if the reports of Pakistan downing Indian aircraft are partially accurate. There’s been a lot of chatter surrounding the implications of a J-10C possibly taking out a Rafale. The obsession with this question is partly because our mind slots it in the same category as the Balakot airstrikes, which ended up in the downing of an Indian Mig-21 in Pakistan-controlled territory. But the situation was quite different this time. Pakistan is claiming that its air defence system took out an Indian aircraft in the Indian airspace, while the Indian side has not accepted any such claims. If true, it is indeed a military gain for the Pakistani Air Force. But even that military win doesn’t change the strategic calculus. Despite this supposed loss, India was able to hit primary military and terrorist targets deep within Pakistan consistently, and that is the more significant development.

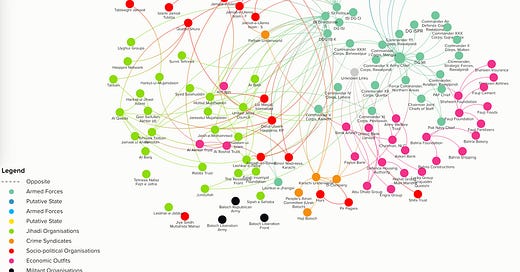

Two, the events serve as a reminder that Pakistan remains a capable military adversary despite its significant economic and social troubles. The military-jihadi complex (MJC) has the first claim on the resources of that country, and it can squeeze out the funds for its requirements, even if the rest of the country suffers. Thus, it would be foolish to discount the MJC’s military capabilities. The dreams of balkanising Pakistan are just as improbable as Pakistani dreams of taking over J&K.

Third, it is fascinating that even in the Information Age, information ecosystems of two adversaries can be managed and partitioned to an extent that each side can claim victory. This is a major takeaway, and we will discuss it in subsequent editions.

For now, we should remember that tackling Pakistan and dismantling the MJC is an infinite game. There is no quick solution.

Bonus: Here’s a map explaining the dense connections between all nodes of the Pakistani military-jihadi complex. It's from a chapter by Nitin Pai and me in the latest edition of the Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Pakistan, ed. Aparna Pande.

India Policy Watch #3: Hold Onto Your Tech Horses

Insights on current policy issues in India

—Pranay Kotasthane

The state of technology reportage is such that every announcement by a company is interpreted as a measure of the technological strength of the country where that company is headquartered. Thus, every little claim by a Chinese research group in obscure journals is hyped as another domain in which China has ‘beaten’ the West. Similarly, every rollback by a company in strategic technology domains is perceived as a failure of the overall national strategy. That’s precisely what happened a couple of weeks ago when Zoho announced it had shelved its plans to build a compound semiconductor fabrication facility. Coming soon after the Adani group failed to lock a deal with the analog chipmaking firm Tower Semiconductors, this announcement sparked many discussions questioning the viability of India's semiconductor mission.

While these developments might seem like setbacks, they do not necessarily indicate a fundamental flaw in India's strategy. In the semiconductor manufacturing segment, project withdrawals at the conceptualisation stage aren't unusual. Fabs take years to build and cost billions, and hence, they need a robust business case. Many projects stall even in mature ecosystems.

Moreover, there are two global forces at play.

Recently, we’ve seen a fab construction boom driven not by market demand but by national security concerns. Many companies have used taxpayer money to start chip fab projects, citing national security as the prime justification. The problem with this strategy is that once all these fabs come online, there is a serious prospect of overcapacity, underutilisation, and revenue losses. This is especially true for fabs making trailing-edge chips, which are unlikely to see the tailwinds due to the AI boom. For this reason, any future trailing-edge, speciality commercial fab would need a strong business case that goes beyond resilience and national security alone.

Secondly, the US-China tariff war has sparked fears of a potential inflation and economic downturn. If that happens, chip demand will also soften. Thus, companies are understandably cautious before making new bets.

Coming to India’s semiconductor incentives. India has globally competitive policy incentives for trailing-edge and compound semiconductors. As I have discussed previously in this newsletter, the initial scheme launched in December 2021 privileged cutting-edge chipmakers. But by September 2022, the government realised that the likes of TSMC had their hands full with demands from other proven ecosystems. Thus, it refined the incentives, giving equal treatment to trailing-edge and specialised chip fabs. The government (state and union combined) is now willing to finance nearly 70 per cent of the total project costs for trailing-edge fabs. It is also willing to provide such firms with import tariff exemptions. Hence, I do not see a problem in India’s incentive structure. The key thing to understand is that venturing into semiconductor manufacturing is a high-stakes game. New entrants like India will inevitably face hurdles.

But here’s what the Indian government can do: execute all existing projects with excellence. The credibility of India's semiconductor roadmap will be determined by its ability to follow through on initiated projects. The Tata-PSMC fab in Dholera and the four OSAT (Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test) plants must start producing chips according to their project plans. Once online, they might need continued policy support until they improve chip yields and operational efficiency. Next, the various training projects for chip design and manufacturing must remain a major focus area. Higher quality of talent will be India’s trump card in the semiconductor game.

Finally, we must remember that building a semiconductor ecosystem is a long-term endeavour that spans decades. We must expect and plan for roadblocks on the way instead of interpreting every announcement as a verdict on the overall strategy.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Podcast] Listen to our Puliyabaazi charting out a manifesto for deregulation.

[Article] This post by Zichen Wang on reporting related to Chinese technological advances is illuminating.

[Podcast] We were on The Seen and the Unseen podcast discussing the caste-based census. Listen in.

Please don't overlook the fact that there is a small percentage of Pakistanis who do not support the military-mullah nexus against India. They want India to have upper a hand and systematically demilitarize Pakistan, so they have a chance at bringing back some semblance of democracy. The political soft power of India must support these elements and defeat Pakistani military, with or without shot being fired. Afterall it is in the interest of India to have a viable Pakistan next door, self-governing and prospering.

Pranay Kotasthane, liked your post on the India-Pak "war". As you said, there was so much news, fake news and the news "one wants to believe" flying around. Look forward to your future posts on that aspect