Back with a new edition of this newsletter. We spent the past 5 weeks trying to work on a few long pending items that needed our attention. Unsurprisingly, the earth went on spinning and nobody missed us. Not much work got done either.

Anyway, things happened in these intervening weeks. We reached a billion vaccine jabs last week. Quite an achievement. We often lament about the ineffective state and the poor health infrastructure in India. But there’s no denying there are times when the state can will its agencies to reach an ambitious target.

The vaccination number was a measurable target, its benefits to people were clear and there was a vaccine administering infrastructure available that’s been built over the years. So, the state moved with speed and purpose because the incentives to get this right were aligned to the government’s desire to strengthen its self-image of being effective and driven. These occasional instances of the state doing its work often lead people to momentarily forget the overreach and the many subsequent failures of the state that are apparent all around us.

There’s a common sentiment expressed in such situations - if only we could tackle all our problems the same way we did this. Unfortunately, the other problems that we must solve as a nation aren’t so unambiguous, their solutions aren’t easy top-down diktats that need to be followed, nor are the interests of everyone so clearly aligned to those solutions. The state will continue to flounder there.

That apart it was business as usual in India. A megastar is being hounded because of what appears like a minor infraction of his son. The underlying motives are open for speculations because the remarkable focus the NCB has shown in this case belies their previous track record in controlling drug use in India. The news channels have picked it up with the same fervour like they did with the suicide of an actor last year. We wrote about that episode here (“A Star Is Dead”).

There was also much brouhaha over how an ethnic retail fashion brand tried to ‘de-Hinduise’ Diwali in their ads. This is now routine during any of the big Hindu festivals. In the arms race of purity, there’s always a marketer who will trip up. The outraged will then take over. #NoBindiNoBusiness is trending as we write. What a time to be alive! Last year there was the Titan ad and we wrote about it here (“That Tanishq Ad”).

Lastly, the largest opposition party in the country took its self-destruction model to yet another state where it is in power. Its ineptitude would have been funny were it not so sad. Democratic accountability rests on the risk of a party losing its mandate in the next elections. A functioning opposition makes that risk real. Congress is dysfunctional now.

India Policy Watch: A Good Representative

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

Talking about politics brings me to a conversation Pranay and I were having last week. It was about the concept of representation and the notion of belonging to a political party. Does a politician represent her people anymore? Does membership of a political party trump all other identities and roles in a democracy? The way things are, maybe M.P. should stand for Member of Party, Pranay half-jokingly said. The party line trumps the individual position, the likely interests of the constituents and the opinions of the experts. The other point he made was how the state governments fight among themselves over trifling issues while missing the big picture. Their interests would be served better were they to unite and demand a better share from the union in a way the federal structure of the Indian state was meant to encourage.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. The anti-defection bill introduced in the 80s made it difficult for an individual member to go against the party ‘whip’. The centralisation of power in political parties and the high command culture that every party defaults to have rendered the members of legislatures powerless. So, the question is what happened here? How did we get here?

Origins of Legitimacy

Let’s hark back to the early phase of modern democracy. The core ideas that emerged from the enlightenment thinkers and political philosophers that powered both the American and French revolutions were about individual liberty and the formation of a state that reflected the ‘will’ of the people. These built the foundation of the liberal democratic order as we know it today. This sounds simple but conceptually there was more happening. The Hobbesian model was that of human multitudes coming together to hand over power and authority to a sovereign through a political structure in abstract called the ‘commonwealth’.

Hobbes defined commonwealth as “One person of whose acts a great multitude, by covenants with another, have made themselves everyone the author to the end he may use the strength and means of them all as he shall think expedient for their peace and common defense.”

For Hobbes, the people willingly transfer the power to one man or to an assembly, agree on being united under that power of commonwealth and use the sovereign to safeguard internal harmony and defend against external threats. Once created, the sovereign could continue to derive its legitimacy from this original covenant of the multitudes or, over time, it could fall back on bloodline or divine right. For Hobbes, the sovereign didn’t need to be representative as long as it used its authority and power like it was designed in the social contract.

The Hobbesian idea of commonwealth and sovereign were great but there were two problems that later political philosophers had with them. First, what circumscribes the power of the sovereign? For Hobbes, it was absolute and that was both good and necessary. Others weren’t so sure. The idea of balance of powers through natural checks and balances was a consequence of that.

Second, what provides legitimacy to the sovereign? Hobbes was only concerned about the multitudes living in peace. So long as the sovereign assured that, it had legitimacy. The later thinkers thought there has to be more to it. That’s how the design of the modern democratic system came to be. There was to be a balance of power between the various arms of the sovereign or the state. The origin of this thought goes back to Montesquieu and his theory of separation of powers. And those controlling the levers of the state will have to pass the test of legitimacy. Winning the mandate to represent the people offered legitimacy. And, therefore, elections became central to conferring this legitimacy to the state.

Things Have Changed

Now, let’s see what’s changed with elections since then?

First, there was an assumption that an average voter knows enough to make an informed and rational choice on who will represent her. This was possible in the pastoral world of the late 18th century. Like we have written before, she is what Lippmann called the omnicompetent citizen. This is no longer possible in the modern world where the average voter only sees a narrow sliver of the world from her perspective. We have ‘pictures in our heads’ of the likely world outside. Political parties create narratives and offer themselves as the best choice by influencing these pictures in our heads.

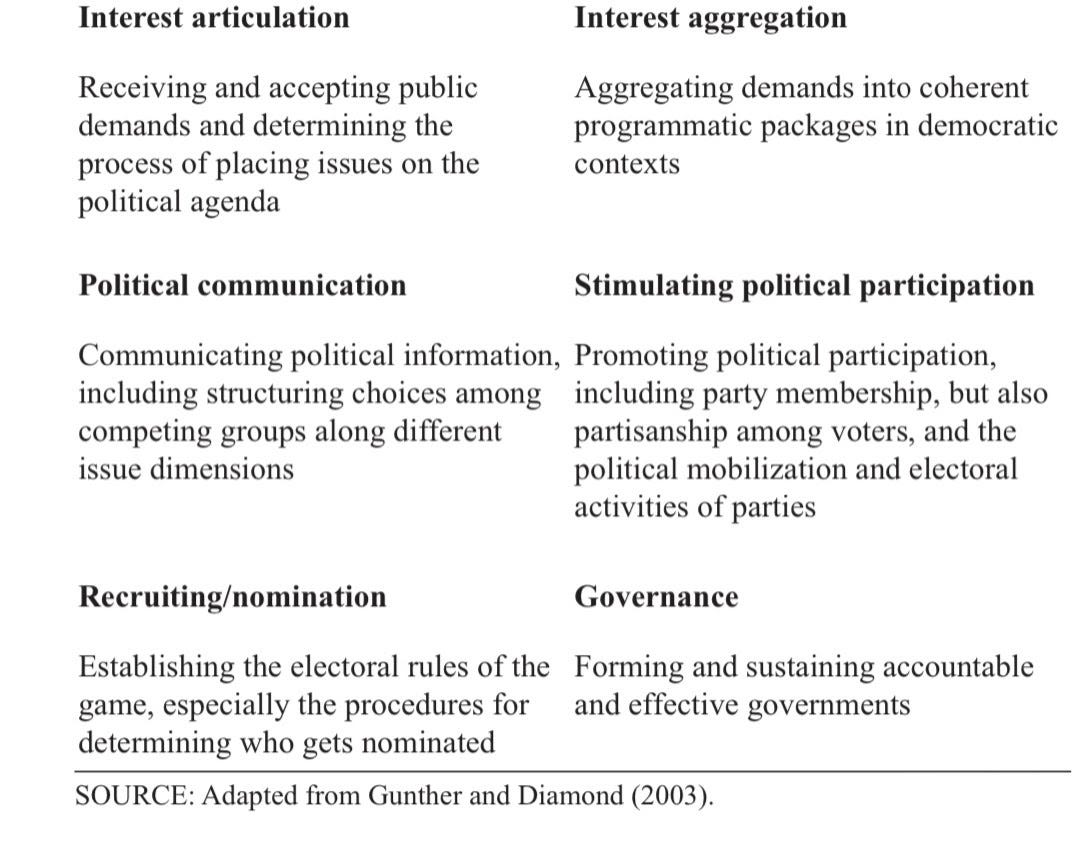

Second, political parties themselves weren’t a fully formed notion in the early years of modern democracy. There was a view that the citizens will choose from among them their best representative who will then legislate laws on their behalf. Political parties were viewed as a partisan coming together of vested interests. As early as 1796, Washington was railing against political parties as factions motivated by ‘spirit of revenge’, compromising on public good and allowing "cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men" to "subvert the power of the people". But as Schmitt would put in many years later, the concept of the political is reducible to the existential distinction between friend and enemy. Therefore, the electoral battle for the spoils of power would make the party system inevitable. In fact, by 1942, E. E. Schattschneider, in his work Party Government, argued “that the political parties created democracy and that modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of parties”. The political party was both useful and indispensable. These key functions of a political party are best summed in the table below:

Third, the role of the representative of the people has undergone a change too. The usual question that comes up on this is whether the representative is a delegate of people or a trustee of their will and aspirations. In the delegate model, the representative is a mere mouthpiece for the will of her constituents and they have limited autonomy of their own. In many forms of direct democracy (or council democracy), this is a norm. The representative was to be subservient to those who she represents. This was also how many viewed representation in the initial years. This was contested by Burke in his famous 1774 speech to electors of Bristol which laid the foundation of the trustee model of representation.

Burke begins with this clear distinction of the role of the representative:

“Certainly, gentlemen, it ought to be the happiness and glory of a representative to live in the strictest union, the closest correspondence, and the most unreserved communication with his constituents. Their wishes ought to have great weight with him; their opinion, high respect; their business, unremitted attention. It is his duty to sacrifice his repose, his pleasures, his satisfactions, to theirs; and above all, ever, and in all cases, to prefer their interest to his own. But his unbiased opinion, his mature judgment, his enlightened conscience, he ought not to sacrifice to you, to any man, or to any set of men living. These he does not derive from your pleasure; no, nor from the law and the constitution. They are a trust from Providence, for the abuse of which he is deeply answerable. Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.”

He then goes on to argue why the conscience of the representative is important for a democracy:

“To deliver an opinion, is the right of all men; that of constituents is a weighty and respectable opinion, which a representative ought always to rejoice to hear; and which he ought always most seriously to consider. But authoritative instructions; mandates issued, which the member is bound blindly and implicitly to obey, to vote, and to argue for, though contrary to the clearest conviction of his judgment and conscience,--these are things utterly unknown to the laws of this land, and which arise from a fundamental mistake of the whole order and tenor of our constitution.”

And goes on to clarify what a Parliament is meant to be. The representative should neither be hostage to the views of his constituents nor of the interests of his party:

“Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests; which interests each must maintain, as an agent and advocate, against other agents and advocates; but parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole; where, not local purposes, not local prejudices, ought to guide, but the general good, resulting from the general reason of the whole.”

And Burke concludes with a point similar to what Pranay made when he defined M.P. as Member of Party:

“You choose a member indeed; but when you have chosen him, he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a member of parliament.”

The centralisation of power in parties in India has meant we now follow neither the trustee nor the delegate model of representation. The representative is beholden to the party alone.

There is another change as well. For years, the continued strengthening of identity politics meant it was more important for the representative to reflect the identity of her constituents than their aspirations. The selection of candidates by parties on caste, sub-caste and community lines across constituencies was the dominant trend. This meant the individual representative could count on his local knowledge and alliances to be useful for a party. So, she could still stand up as an independent voice of judgment secure in her strength like Burke envisaged when needed. But this is now being reshaped by the dominant party in India. The nationalist, Hindu and resurgent India narrative might likely subsume the local identities and the natural balance of power that was available in the Indian polity. This has made the dominant political party today stronger than the sum of its parts and consolidated power in the ‘high command’ further.

This is an interesting time to contemplate on representation in a democracy like India. We chose universal adult franchise at the time of independence much ahead of many other nations. This was fundamental to the right of equality that the Constitution guaranteed. The social re-engineering phenomenon that dominated most of our politics between 60s-90s was an outcome of this right given to every citizen. The representative might not have been a trustee in the way Burke thought of her. She might have been toeing the party line on most issues. But she ‘reflected’ the ‘narrow’ identity of the people she represented and this mélange of narrow identities coming together in the parliament possibly made the democratic system more robust.

What we have now is a gradual shift to a more dominant single-party system with a greater focus on what can be called the One Nation, One “X” philosophy. This sounds seductive in the aggregate especially if your definition of the imagined construct of the Indian nation aligns with what’s being promoted. Will it make democracy stronger? The odds are stacked against it if history is any guide.

A Framework a Week: Confronting Trade-offs

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

A common folly in policy analysis and commentary is the inability to confront trade-offs of well-intentioned, nice-sounding government actions such as the European Commission’s recent proposal mandating a common charger for electronic devices.

Not that confronting trade-offs is easy in business or household decision-making but the problem gets acute in public policy. A recent study finds that even people who consider trade-offs in private consumption fail to do so while thinking of government actions. Opportunity cost neglect is a way more serious issue when governments are involved. I suspect three reasons might be at play here.

One, we as individuals do not feel connected to the money government spends although it’s we who pay for the expense in the form of taxes. So we ignore the costs and get anchored to the benefits promised by a government policy. Two, some analysts instinctively think that the government is the right agency to solve all our problems regardless of the nature of the problem itself. Three, we ignore the implementation capacity required to put the solution in place.

Even so, there’s no getting away with confronting trade-offs. Because actions of the State have wide-ranging effects on large sections of its citizens, even the worst-possible policies might have some benefits. Remember how the then Finance Minister claimed that terror funding with fake notes had gone down because of demonetisation? Similarly, even the most well-intentioned, impactful policies will have negative consequences and will make some people worse-off. Consider how the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for grains did perhaps help India defy Malthusian predictions but it also led to ecological and environmental issues that the future generations are condemned to face.

Given that a perfect policy with only benefits and no costs is yet to be devised, how does one go about evaluating any public policy proposal? I have a four-step heuristic to help.

Step 1. Try to anticipate the unintended consequences. Economic reasoning, history, and the social context are some good guides that can help in this step. We have discussed how to anticipate the unintended here.

Step 2. Once you have identified the unintended consequence and the people who are likely to bear these effects, check if the policy has measures to try and align their interests. If not, it might be subverted through direct opposition. As is the case with the ongoing farmer agitation. Or the purpose could be defeated by taking over-ground activities underground.

A good hack for this step is to think about how drastically a policy changes the incentives of the current players. The more drastically it does, the higher likelihood that it will be subverted. The red flags to watch out for are bans, high rates of taxation, or imposition of huge penalties.

Step 3: Do intellectual, financial, regulatory, and compliance capacities to carry out the proposal exist? Ignoring capacity leads to implementation failures.

Step 4. Consider whether anticipated benefits outweigh anticipated costs. Standard cost-benefit analysis techniques can be deployed here.

A hack for this step is to analyse if the policy measure has well-defined endpoints or sunset clauses baked in. If yes, undesirable effects can be reigned in; the policy is amenable to negative feedback. If not, the policy measure can lead to difficult-to-measure intergenerational effects.

A PolicyWTF Charge

With this framework in mind, let’s analyse the EU Commission’s proposal mandating a common charger (USB-C) for electronic devices. Read the excellent background documents on the commission’s website here.

The stated intent of the policy is two-fold. One, reducing consumer inconvenience because of multiple chargers. And two, reducing e-waste. Lofty goals, who could possibly oppose that these aren’t problems that need to be solved.

The evidence presented for these two problems is as follows:

“In the European Union, approximately 420 million mobile phones and other portable electronic devices were sold in the last year. On average, a consumer owns around three mobile phone chargers, of which they use two on a regular basis. 38% of consumers report having experienced problems at least once that they could not charge their mobile phone because available chargers were incompatible. The situation is inconvenient and costly for consumers, who spend approximately €2.4 billion annually on standalone chargers that do not come with their electronic devices.

In addition, disposed of and unused chargers are estimated to represent about 11,000 tonnes of e-waste annually. A common charging solution is expected to reduce this by almost a thousand tonnes annually.”

The benefits sound great. If one were to read an analysis that presents the above problem, evidence, the proposed solution seems obvious and indispensable almost.

But wait, now let’s apply the framework we discussed.

Step 1: The EU Commission is making a choice on consumers’ behalf that the ease of using one charger is more beneficial to them than the benefits that different charging technologies may offer. For example, one technology could be charging faster, it might be lighter etc. Next, it is locking users into another technology USB-C, which itself might get outdated in a few years. Third, this measure ‘disincentivises’ manufacturers from developing new charging technologies.

Step 2: I don’t see any major issues with aligning the interests of stakeholders as this measure impacts just one company today that has a proprietary charging solution (Apple) and perhaps the EU wants it to pay. The ban on other charging technologies should make us circumspect.

Step 3: Capacity is not a big issue in the EU assuming they just need to control a handful of manufacturers.

Step 4: Weighing costs and benefits is where this policy has severe drawbacks.

The benefits are marginal. For one, there are just three major charging technologies in the market, down from 30 a decade ago. Two, the cost-saving per consumer is ~€6 annually (=€2.4 billion/446 million population). Three, this measure is expected to reduce the charger e-waste by a mere 10 per cent.

An impact assessment study on the EU Commission itself has this to say:

“Environmental impacts: [The USB-C solution and some such solutions] only have very minor, potentially negligible (no more than 1.5% change compared with the baseline) impacts on the environment, as they are expected to lead to very small changes in the number of chargers sold, as well as, in some cases, to changes in the types of chargers sold (with very minor impacts on their weight and composition).”

Economic impacts: This option delivers relatively high economic costs for manufacturers and distributors, and may slightly constrain innovation. It may also entail minor economic costs for SMEs in the EU.

Social impacts: [The USB-C solution and other such solutions] are all expected to result in minor convenience benefits for consumers, as well as very small improvements in terms of product safety and illicit markets (mainly due to the expected very small reduction in stand-alone charger sales).

On the other hand, the costs to manufacturers and consumers to transition to another technology are substantial. From the same report:

“This option [USB-C mandate] could potentially have a major negative effect in terms of reducing future innovation in phone connectors, both by effectively ruling out any new “game-changing” proprietary connector technology, and by potentially reducing the pace of “incremental” innovation as regards future generations of USB connectors, and limiting the characteristics that this future connector might have… If companies are not given the choice to remove receptacles, it may however have a significant indirect impact on innovation in wireless technologies.”

So, as we dive deeper, the shine of promised benefits gets dulled by the impact of probable costs. Other solutions such as unbundling chargers and phones seem to have a better cost-benefit trade-off.

Beware of intuitive solutions to complex policy problems.

HomeWork

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Book] Political Representation by F.R. Ankersmit

[Podcast] As the peak-air pollution days come closer, listen to this Puliyabaazi on the science of air pollution.

Share this post