(From The Archives) How To Anticipate The Unintended? Private Vices Lead To Public Good

Regulation is a pedagogical bad. Consumption is a pedagogical good.

Programming Note: We are on a short ‘writing’ break. Normal service will resume from Oct 24. Meanwhile, here are two essays from our archives.

Regulation is a pedagogical fail

Tools for thinking public policy

— Pranay Kotasthane

(From our edition #1 on Oct 25, 2019)

A couple of years ago, Pavan Srinath pointed me towards this excellent paper: Why public goods are a pedagogical bad. I have now come to the conclusion that the term regulation deserves the same treatment: it is a pedagogical bad, so ambiguous that it is virtually meaningless.

I say so because of two reasons.

One, the word just implies too many things. For instance, if I say that bitcoin should be regulated, this statement offers zero insight into the precise government intervention that is being referred to. It is unclear whether regulating here means banning bitcoin, imposing a price cap for trading in bitcoins, or imposing an entry license that permits this trade.

Just have a look at the list below from an excellent public policy textbook — Eugene Bardach’s A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis. The range of actions that get classified as regulation range from outright bans to merely improving complaint mechanisms. When one term can mean so many distinct things at once, it is of little help as an analytical tool.

The second reason for why regulation doesn’t make sense is because there is NO industry or sector that is completely unregulated. So, when someone says that xyz sector should be regulated, I’m at a loss because I’m pretty sure that there might be some — perhaps insufficient —regulatory intervention already in place.

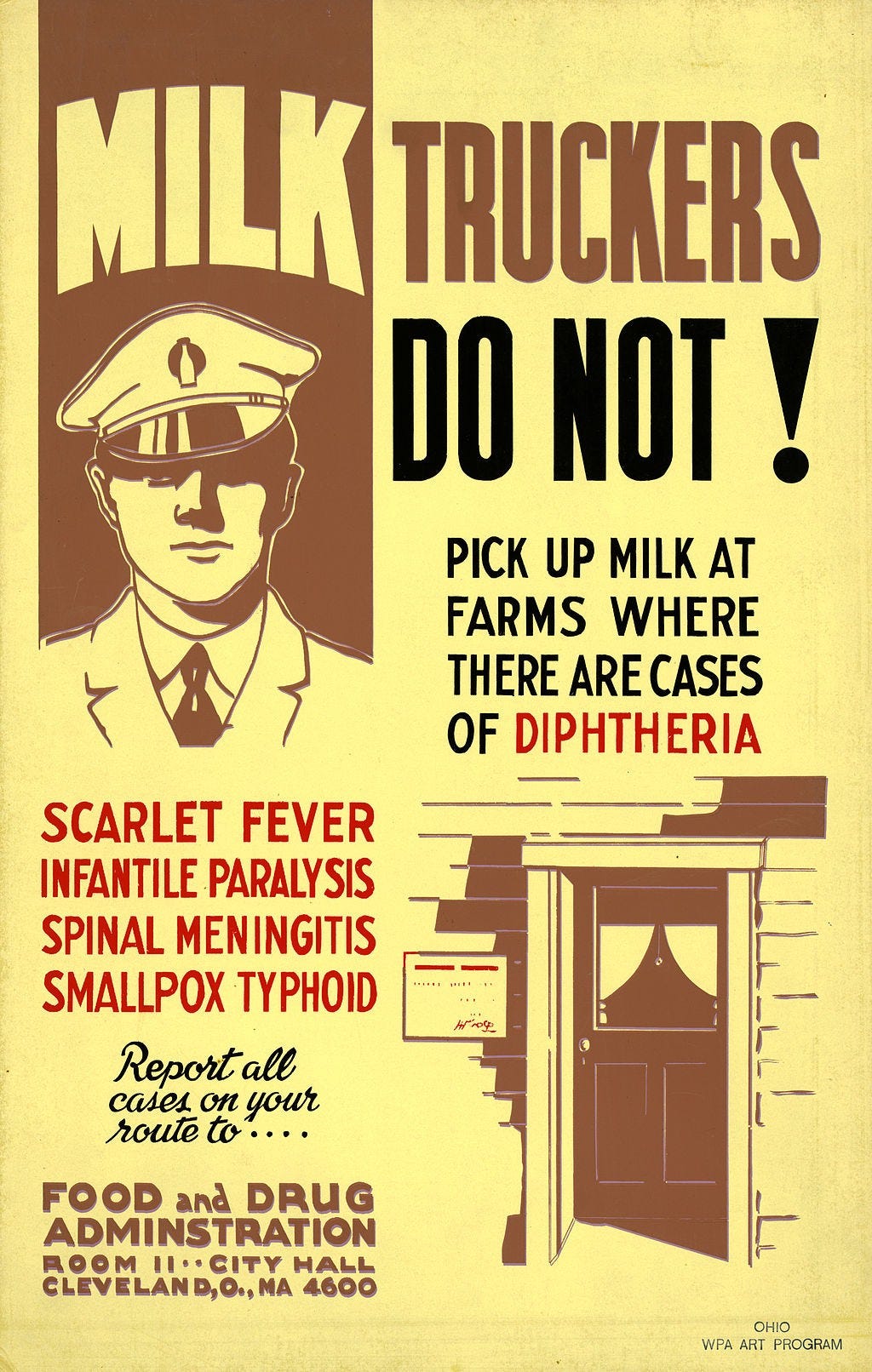

Regulation of the Milk Supply by USFDA (Source: Wikipedia)

For example, when someone talks about regulating private hospitals, it does not mean that the hospitals are unregulated today. There are many entry and exit criteria that these hospitals are already adhering to: from the space required for each ward bed to the minimum number of human resources, there are an extensive set of ‘regulations’ that are already in place (see the Clinical Establishments Act Standards from 2010).

If regulation is a pedagogical fail, what are the alternatives?

Instead of using the leaky umbrella term regulation, Anupam Manur and I were able to break the term down into the following categories. This is perhaps not an exhaustive list. All suggestions for improvement are welcome.

No further regulatory intervention required. The government can choose to ignore calls for tightening control. For example, a government may choose to ignore calls for caps on private school fees.

Output quantity controls. An extreme form of this intervention is a ban on the production of a good. A common form of this intervention is to allow production of a good or service but to restrict the quantity that can be produced. For example, industrial licenses in the pre-1991 era had restrictions that prevented companies from producing beyond a license capacity threshold.

Output type/quality controls. Mandating the disclosure of information is a common way of controlling the type and quality of controls. By making tax filing and audits compulsory, or by making it necessary for food marketing companies to disclose nutrient information on their products, the government controls the type and quality of outputs required. Setting pollution emission standards is also, in effect, an output quality control measure.

Output recipient controls. Governments can also restrict where the outputs go. Export restrictions fall under this category of regulation. So do priority sector lending mandates for banks.

Input quantity controls. For example, the Indian government specifies a reserve requirement for banks in the form of gold, government-approved securities before providing credit to the customers (referred to as the Statutory Liquidity Ratio).

Input type/quality controls. Reservations in jobs are an example of controlling the type of input. Worker safety regulations translate into specific inputs such as requiring the presence of a doctor on-site in a workplace.

Input provider controls. Through import restrictions, for example, governments prevent inputs from outside the country. Another example is a regulation that prevents monopoly formation by mandating that the supply-chain of a company cannot be owned by the same company.

Imposing output price controls. Price ceilings and price floors are commonly used regulations and constitute a separate category.

Entry controls. Governments can specify the conditions that need to be met even before firms can start production. For example, it is mandatory that a hospital cannot begin operations without a registered medical practitioner on its payroll. Another example: governments prescribe a lower limit for the capital required before an individual can launch a bank.

Exit controls. Governments can specify the conditions that need to be met before firms can stop production. For example, bankruptcy laws specify what firms need to do before closing down operations entirely.

Most importantly, each of these controls has different intended and unintended consequences. And ‘regulation’ conflates all of them.

So, the next time someone says that xyz sector of the economy should be regulated, ask them to explain which of the ten controls are they referring to? What will be the unintended consequences of that measure? And, are those risks worth taking up?

India Policy Watch #1: Consumption And The Fable Of Bees

Insights on burning policy issues in India

— RSJ

From our edition #68 on Sep 13, 2020)

‘The pandemic has shown us what is truly important in our lives.’

‘We learnt to go slow and consume only that we need during the lockdown. That’s one lesson we should follow beyond the pandemic.’

‘The earth is healing as the pandemic has forced us to slow down our lives and reduce our greed.’

Every couple of weeks I come across a column that argues on similar lines as above since the pandemic began. I guess we have a great desire to search for a silver lining in the bleakest of scenarios. But this is exactly the kind of silver lining we should avoid. The idea we learn to reduce consumption so the earth can sustain our load doesn’t have any underlying logic. Worse, such reduction will harm the vulnerable and the poor the most. But, hey, good intentions are all that matter, right?

Any discussion on consumption as a vice takes me back to Mandeville and his work ‘The Fable of Bees’ which has a deserving claim of being among the most provocative and counter-intuitive texts of all time. Published in the early 18th century, it’s alternative title, Private Vices, Public(k) Benefits establishes its central thesis upfront. The book is in three parts. The first part is a poem, The Grumbling Hive, which is followed by an essay discussing the poem. The book concludes with an essay An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue that lays out his defence of vice. This essay, as we will soon see, is a proto-text for different schools of economic and moral philosophy that emerged during and after the age of enlightenment.

The Wages Of Virtue

The Grumbling Hive is a simple poem of uncertain literary merit. There’s a hive of bees that live in ‘luxury and ease’ while giving virtue, moderation and restraint a short shift. Instead of being happy with this prosperity, the bees question their lack of morality and wonder (or grumble) if there wasn’t a more honest way to lead their lives. Some kind of divine power grants them their wish and their hearts are filled with virtue now. This turn to an ethical hive however comes at the cost of prosperity.

Ease was a vice now, temperance a virtue and the industry that emerged from the bees competing with one another disappeared since the virtuous bees didn’t bother any further with competition. This lack of industry meant a fall in prosperity. Many thousand bees lost their lives, and society started collapsing. The bees weren’t deterred. They flew into a hollow tree that suited their new lifestyle of restraint. They were content being poor but honest.

Mandeville questions the social benefit of this trade-off.

What good is this virtuous life which keeps everyone poor?

This leads him to make the almost blasphemous claim that vice is good so long as it is within bounds of justice. Not just that he also bats for people as a resource. People are not a burden for society.

This was incendiary material then. And I guess, even now. He wrote:

So Vice is beneficial found, When it’s by Justice lopt and bound;

Nay, where the People would be great, As necessary to the State,

As Hunger is to make ’em eat.

And after having set the Thames on fire, he concludes the poem with these famous lines:

Bare Virtue can’t make Nations live In Splendor;

they, that would revive A Golden Age,

must be as free, For Acorns, as for Honesty.

With this, Mandeville earned his lifelong notoriety as a libertine of dubious morality. It didn’t bother him and his later defence of thievery and prostitution as public good suggests it possibly fuelled his desire to be more outrageous.

Private Vice, Public Benefit

In his essay ‘An Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue’, Mandeville explains the paradox of private vice and public benefit further. Mandeville makes three key arguments:

A virtuous act is one that’s unselfish and driven by reason. Acts that are selfish and involve raw passions were vices. Mandeville goes about looking for virtuous acts in society and draws a blank. However, he finds there are acts beneficial to the society that don’t qualify as virtues. He concludes individuals might pursue their self-interest (vice) but on an aggregated basis this might be creating a societal good. For example, members of a society might quarrel among each other pursuing their interest, but that quarrel generates employment for lawyers, clerks and judges. If they were to turn virtuous, this public benefit would disappear.

The natural state of man (the term used in the text which we will use here) was to be selfish. The individual was a ‘fallen man’ who was selfish and sought pleasure only for himself. This vice was the foundation of the society and all social virtues emerged from self-interest. Vice is good. To Mandeville, virtue was a state of denial of this natural state.

Even virtue that man displays is rooted in vice. A man acts with virtue for two reasons –either to satisfy his ego (vanity) of being seen as virtuous by the society or to not offend the ego of his peers. This is a facade to cover the underlying greed or selfish motives that give him private pleasure. These days we might call it virtue signalling.

This cynical take on man and society didn’t earn him friends. The act of calling virtue a facade was unacceptable in a society whose foundation was the Christian notion of virtue. The idea that a human couldn’t do a virtuous act without self-denial negated the concept of a religious man being a superior person who could rise above primal passions. There were multiple attacks on The Fable of Bees from moral and political philosophers of the time.

Yet the text survived for two reasons. One, in its belief that the society is held together by individual acts of self-interest of many and not by some kind of faith in the divine, it was the first attempt at separating social science from the clutches of theology. This was already achieved in natural sciences with scientists like Galileo, Copernicus and Newton challenging religious orthodoxies through the scientific method. The time was ripe for questioning the role of religion in social sciences too. Two, there was something liberating about a text that didn’t speak about how humans should be. Instead, it was a realist’s view of how humans behave in nature and that behaviour at an aggregated level produces social benefits. This was a powerful insight that advocated individual liberty.

The Long Shadow Of The Fable

The Fable of Bees served as inspiration for a wide range of philosophers over the course of the next two centuries. Hume agreed with the basic premise of Mandeville that the sense of morality or virtuousness in a man occurs only in a community or a society through aggregated acts. Hobbes drew from Mandeville on self-interest being the primary motivation for human action. Adam Smith was inspired by the notion of aggregated self-interest producing social good though he disagreed with Mandeville by bringing in the role of sympathy. He also thought vanity alone wasn’t the reason people acted with virtue. There was a desire for true glory too. As Smith wrote in The Theory of Moral Sentiments:

“It is the great fallacy of Dr. Mandeville's book to represent every passion as wholly vicious, which is so in any degree and in any direction. It is thus that he treats everything as vanity which has any reference, either to what are, or to what ought to be the sentiments of others: and it is by means of this sophistry, that he establishes his favourite conclusion, that private vices are public benefits.”

Yet Smith accepts there is a kernel of truth in Mandeville’s core assertion:

“But how destructive so ever this system may appear, it could never have imposed upon so great a number of persons, nor have occasioned so general an alarm among those who are the friends of better principles, had it not in some respects bordered upon the truth.” (emphasis ours)

While the fable of bees influenced Smith and his methodological individualism, it also left a mark on Rousseau and the French collectivists who followed him. Rousseau agreed with Mandeville on the lack of social or public-spiritedness in man in the natural state. However, Rousseau introduced ‘pity’ or a “natural repugnance at seeing any other sensible being and particularly any of our own species, suffer pain or death” as natural sentiment within a man. This pity overrode self-interest and became the reason for other virtues.

It isn’t too difficult to see how Mandeville’s philosophy became the founding text for the economic theory based on the primacy of individual liberty and limited intervention of the state. If individual acts of self-interest could lead to social good, what was the need for any intervention by anyone? This was the argument of Friedrich von Hayek who took the fable of bees as the first text that advocated ‘spontaneous order’. He wrote:

“It was through asking how things would have developed if no deliberate actions of legislation had ever interfered that successively all the problems of social and particularly economic theory emerged. There can be little question that the author to whom more than any other this is due was Bernard Mandeville.”

In a similar vein, Ludwig von Mises (Hayek’s peer from the Austrian school) explained, in Theory and History (1957):

“Only in the Age of Enlightenment did some eminent philosophers . . .inaugurate a new social philosophy . . . They looked upon human events from the point of view of the ends aimed at by acting men, instead of from the point of view of the plans ascribed to God or nature . . .

“Bernard Mandeville in his Fable of the Bees tried to discredit this doctrine. He pointed out that self-interest and the desire for material well-being, commonly stigmatized as vices, are in fact the incentives whose operation makes for welfare, prosperity, and civilization.”

While Hayek and Mises were crediting Mandeville for being the first to articulate spontaneous order, their great intellectual rival, Keynes, was finding merits in the fable of bees too. Keynes’ Paradox of Thrift is the intellectual progeny of the Private Vice, Public Virtue paradox:

“For although the amount of his own saving is unlikely to have any significant influence on his own income, the reactions of the amount of his consumption on the incomes of others makes it impossible for all individuals simultaneously to save any given sums. Every such attempt to save more by reducing consumption will so affect incomes that the attempt necessarily defeats itself. It is, of course, just as impossible for the community as a whole to save less than the amount of current investment, since the attempt to do so will necessarily raise incomes to a level at which the sums which individuals choose to save add up to a figure exactly equal to the amount of investment.”

The state could get itself out of a recession by stimulating demand and increasing consumption while it could dig itself into a bigger hole by reducing consumption. Keynes credits Mandeville’s work in his General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money for highlighting consumption (aggregate demand) as the principal engine for economic prosperity.

It is possible Mandeville wasn’t aware of the profound implications of his fable when he wrote it. He was possibly baiting the hypocrites of the society of his time who hectored others to live in virtue while committing vices themselves. It is also likely he was being ridiculous for the sake of infamy since he seemed to enjoy riling up people. But given his influence on the entire spectrum of philosophical and economic thought – from individualism to collectivism and from statism to laissez faire – I’m inclined to side with Adam Smith.

Mandeville’s fable borders on a fundamental truth – private vices may lead to public good.

May I pass on my compliments to RSJ, whose writing I have recently become acquainted with, for his excellent analysis, lucid style and envy worthy frameworks to view the world! And you too Pranay. When are you guys coming out with a book or a compilation of all your writings on kindle. Thanks!